My buddy John Horgan brought Sabine Hossenfelder to Stevens Instituted to talk about her current book, Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray. Her argument is simple: The foundations of physics – general relativity (space and time) and the standard model of particle physics – is in trouble because it has become besotted with beauty. Theory no longer generates testable prediction. It just generates more and more theory.

But what’s beauty? I’ve been hearing about intellectual beauty all my life. I even believe in it, sorta’. It seems that theoretical physicists are obsessed with it.

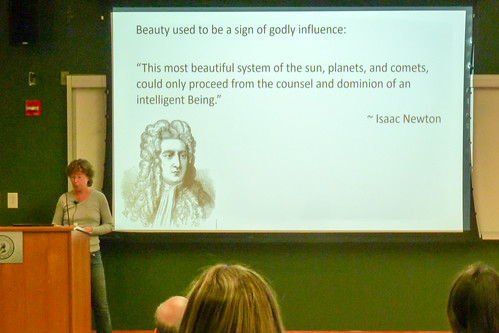

I’ve been reading about Hossenfelder’s book for some time now, and I’ve even visited her blog, Backreaction, so I’m familiar with her thesis. Still, I was struck when she put up slide after slide of physicists extolling beauty. Why?

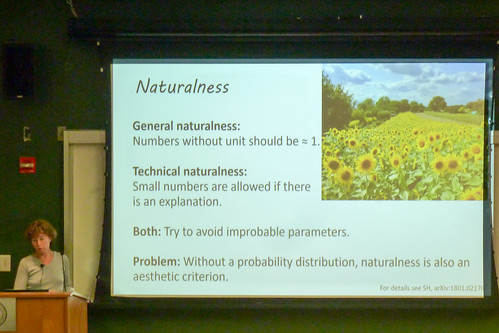

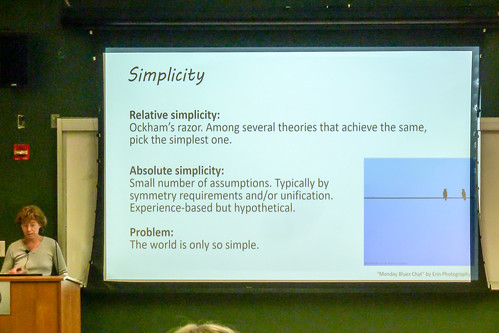

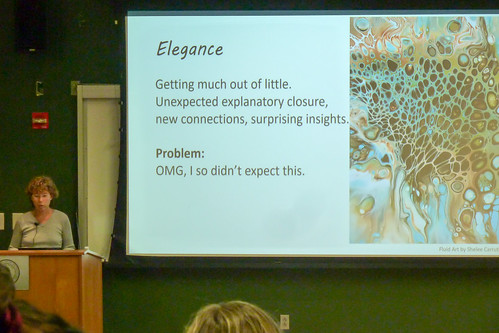

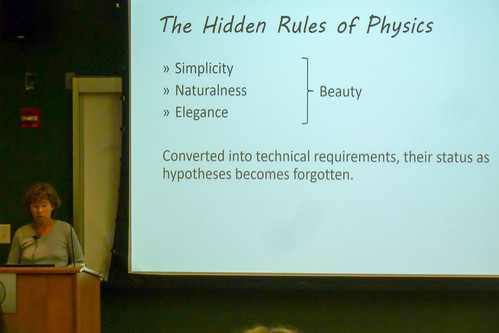

It seems that beauty has become a quasi-technical idea among physicists working on foundations. She interviewed a number of physicists to get an idea of what they meant. It boils down to simplicity, naturalness, and elegance.

These aesthetic requirements may, in some abstract sense, be plausible. It would be nice if things worked out this way, but . . . they haven’t, not for the last several decades. In particular, they have failed to generate predictable observations for the Large Hadron Collider at CERN. The Higgs boson, that’s it, and it was predicted back in 1964.

Turning simplicity, naturalness, and elegance into technical requirements (on physical theory) has been a disaster. There is no a priori reason the universe HAS to be this way. Beauty thus seems to be an arbitrary requirement that physicists are projecting onto nature for their own reasons, and those reasons no longer seem to have anything to do with truth.

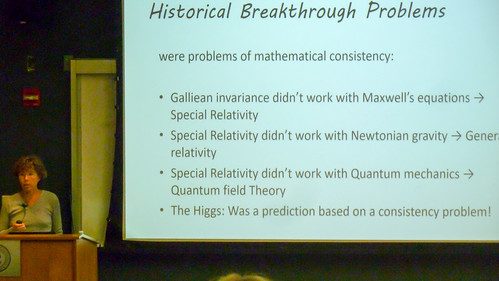

Hossenfelder points out that, historically, physics has advanced by resolving inconsistencies. “Lack of beauty is not an inconsistency.”

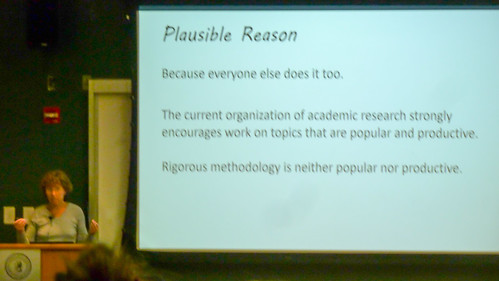

OK, theoretical physics isn’t working. So why do they keep at it?

That’s why.

Hossenfelder goes on to point out that the similar problems seem to exist in other scientific disciplines. The mechanism is broken, but they keep turning the crank.

What to do?

* * * * *

I’ve got some general observations. First: I've been hearing a lot of physicists saying, Philosophy! We don't need no stinkin' philosophy. Yes you do, yes you do, you quark porkers, you hadron humpers! And that's why, that up there.

Not, mind you, that I have any great faith in the current batch of philosophers. Some may be up to, but I don’t really know. Rather, it’s that the problems Hossenfelder is dealing with are fundamentally philosophical in kind – here I’m thinking of some remarks that Peter Godfrey-Smith has made in explication of Wilfred Sellars (see this post, What is Philosophy?). For example, I sense that that obsession with beauty has underpinnings that need to be investigated. Hossenfelder’s right, it’s an arbitrary imposition. It’s not mere institutional inertia that’s keeping it around. What work is it doing for physicists? It has a theological feel about it, a whiff of incense. [In a blog post today Hossenfelder points out, as she did in her lecture: “These arguments trace back to tales about God’s beautiful creations.”]

Second: Early on Hossenfelder pointed out that the foundations of physics is working from a set of ideas that had come together by the mid-1970s. Bingo! That when academic literary study reached its peak, or so I argue in a working paper, Transition! The 1970s in Literary Criticism. That’s when deconstruction finally vanquished structuralism and became the avant-garde approach of choice. By that time feminism and African-American studies were on the rise, cultural studies too, and the New Historicism beginning to bubble up, making its full appearance in 1983 with the founding of the journal, Representations.

Now, I’m certainly not suggesting any causal connections between theoretical physics and literary studies, nor even an ethereal cultural resonance. I AM suggesting that the difficulties extend beyond the sciences and that we seem to be experiencing a widespread collapse of intellectual frameworks inherited from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Work within these frameworks was brought to maturity in the post-war decades and now seems to have advanced into a doddering senescence.

To a first approximation, everything is going wrong. Everything needs to hit the reset button and start anew.

Finally, I note that I addressed this general issue back in the mid-1990, when I reviewed John Horgan, The End of Science: Facing the Limits of Knowledge in the Twilight of the Scientific Age (1996). That review is available online, Pursued by Knowledge in a Fecund Universe.

No comments:

Post a Comment