Way back at the end of September I posted the first of a two, possibly three, post series: Notes toward a theory of the corpus, Part 1: History. I figured the second post would follow within a couple days and perhaps a third a few days after that.

I got delayed, diverted by other matters. But here we are with the second post.

As I said at the beginning of that post, by corpus I mean a collection of texts. The texts can be of any kind, but I am interested in literature, so I’m interested in literary texts. What can we infer from a corpus of literary texts?

Then I was interested in history. This time around I’m interested in the mind. History and the mind, two different, but not unrelated, phenomena. The fact that a given corpus consists of text by many different authors is essential to making historical inferences. The different authors published at different times; we can use a corpus of those different texts to arrive at inferences about historical process. In that earlier post I used Mathew Jockers’ Macroanalysis as my example. He had a corpus of 3300 Anglophone novels from the 19th century.

In this post I’ll be using Matthew Gavin’s work on a passage from Paradise Lost [1]. He uses a corpus of 18,351 documents drawn from Early English Books Online and dating from 1649 to 1699 (which covers the years when Milton wrote and published his epic). I don’t know how many authors are included in the corpus, but it doesn’t matter. Gavin is interested in only one of those authors, John Milton. And while he says nothing about Milton’s mind, he writes only about his text, I will argue that he is, in fact, investigating Milton’s mind. But also the mind of any sympathetic reader of Paradise Lost.

How is that possible? On the contrary, how is it not possible?

The corpus in vector semantics

For reasons I’ll explain shortly, if only superficially, Gavin needed a large body of texts to create a vector semantics model he could use in investigating Milton. I don’t know how many words were in those 18,000+ texts, but if each text were, on average, 10,000 words long, that would be a total of 180 million words; 50K words each would yield a corpus of 900 million words. I figure we’re dealing with 100s of millions if not over a billion words or continuous text. If Milton had written a lot Gavin could have used a corpus consisting entirely of Milton’s own texts. Milton didn’t, so Gavin couldn’t.

However many authors are included in that corpus, each has their own mind. And, at the margin, their own idiolect as well. Still, they hold English as a common tongue; if it wasn’t pretty much the same for each of them it wouldn’t function as a medium for communication. As long as we remind ourselves of what we’re doing, we can treat the lot of them as one somewhat idealized corporate author of the texts in the corpus. It is the semantics of that author that Gavin is applying to Paradise Lost.

Given our corpus, how do we create a semantic model? At this point I am going to more or less assume that you’ve already been through a good explanation of how vector semantics works. But I’d just like to remind you of some aspects of the process.

The process is founded on the assumption that words that occur close together in texts share some aspect of meaning. How can we turn that insight into a usable model? We create a co-occurrence matrix.

Here I’m using an example from Magnus Sahlgren [2]. Consider this text from Wittgenstein, “Whereof one cannot speak thereof one must be silent.” It contains nine word tokens from eight word types, to use terms from logic (one appears twice). Now we need to define what we mean by “close together”. Given two words, are the considered to be close if they are, for example, 1) within they same 1000 word string, 2) immediately contiguous, or 3) something else? For this example let’s choose the second criterion.

Given that, we can produce the following table:

whereof

|

one

|

cannot

|

speak

|

thereof

|

must

|

be

|

silent

| |

whereof

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

one

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

cannot

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

speak

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

thereof

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

must

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

be

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

silent

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

It makes no difference whether we read by rows or columns as they are the same, but let’s read it by rows. If the word in a column is next to the target word we place a “1” in the column, otherwise “0”. So, whereof does not occur next to itself; a 0 goes in the first column. It does occur next to ˆ; a 1 goes in the next column. An so it goes for the rest of that row and for the rest of the rows.

Note that as whereof is the first word in our text it can have only one word next to it. The same is true for silent, the last word. Since one occurs twice it is next to four other words. The remaining five tokens – cannot, speak, thereof, must, be – each have two neighbors, one before and one after.

Each word is not associated with a string of eight numbers, which we can call a vector. We can now use those numbers to associate each word with a point in a space of eight dimensions, one for each word. In practice we wouldn’t bother with a corpus consisting of only one short text. But the principle remains the same given a corpus of 100s of millions of words constructed of tokens drawn from a population of, say, 100,000 types. Define what you mean by context and construct a co-occurrence matrix for your 100,000 types. Now you can associate each type with a point in a space of 100,000 dimensions – a rather breath-taking notion.

That’s the general principle. Various methods can be used to reduce the number of dimensions we have to deal with, but regardless of how it is done we still end up with many more than three dimensions, which is the limit of what we can conveniently visualize. None of that matters to us. What matters to us is simply that we can associate the meanings of words with points in space and perform various operations in that space.

Thus we have what has become the paradigmatic example for vector semantics [3]:

1) king - man + woman = queen

Other kinds of operation are possible:

2) paris - france + poland = warsaw

3) cars - car + apple = apples

All of these are based on analogies where a word is missing:

A : B :: C : ?

Remember, where you and I see a word the computer model sees a point in space, a point defined by a vector, which is a string of numbers. In each of these three cases it starts with a vector (that is, a string of numbers), subtracts a second vector from the first, then adds a third vector to that result, yielding a fourth vector, another point in space. The point is our answer.

You and I may know the meanings of these words (examples 1 and 2) and the rules for pluralization (example 3), but the computer model knows none of that. It knows only the relations between word types that it can infer from the word-space constructed from the co-occurrence matrix based on the contexts in which word tokens occur.

Gavin, however, isn’t interested in such analogies. Well, yeah, I rather suspect that he’s very interested in the fact that one can do such things with vector semantics, but that’s not what he does with the model he’s constructed. He uses it to examine a passage from Milton.

As I mentioned at the outset, his co-occurrence matrix is based on 18,351 documents drawn from Early English Books Online. The structure in each of those documents must necessarily come from the mind of the document’s author. As those authors speak a common language we may, as I’ve argued above, think of the structure in that co-occurrence matrix as coming from the mind of a somewhat idealized corporate author of the corpus. Gavin is, in effect, asking that author to read a passage from Paradise Lost while we look on over their shoulder, as it were.

That may not be how Gavin thinks of what he’s doing, but it’s how I’ve come to think of it. Call it a virtual reading.

Reading a passage from Paradise Lost, but virtually

Gavin examined eighteen lines from book 9 of Milton’s Paradise Lost (455-472):

1) Such Pleasure took the Serpent to behold

2) This Flourie Plat, the sweet recess of Eve

3) Thus earlie, thus alone; her Heav’nly forme

4) Angelic, but more soft, and Feminine,

5) Her graceful Innocence, her every Aire

6) Of gesture or lest action overawd

7) His Malice, and with rapine sweet bereav’d

8) His fierceness of the fierce intent it brought:

9) That space the Evil one abstracted stood

10) From his own evil, and for the time remaind

11) Stupidly good, of enmity disarm’d,

12) Of guile, of hate, of envie, of revenge;

13) But the hot Hell that alwayes in him burnes,

14) Though in mid Heav’n, soon ended his delight,

15) And tortures him now more, the more he sees

16) Of pleasure not for him ordain’d: then soon

17) Fierce hate he recollects, and all his thoughts

18) Of mischief, gratulating, thus excites.

I’ve highlighted words that Gavin identified for specific attention, but before commenting on them I want to offer a paraphrase of the passage, a minimal reading as Attridge and Staton [4] call it:

Satan, in the form of the Serpent, comes upon Eve in the garden and is overcome by her beauty. For a moment thoughts of evil are gone and he harbors no ill intent toward her. But as he continues to view her, the knowledge that he cannot have her terminates his pleasure and he hates her (again).

That is to say, the passage follows a movement in Satan’s mind, movement I’ll consider in a bit.

But first, to Gavin. After citing some traditional criticism of this passage, Gavin, without really saying why, zeros in on line nine–though I note that the last bit of criticism he cited was about that line. Note that, as the whole passage is 18 lines long, that line is at the passage’s center. When you drop out the stop-words–that, the, and one–we are left with four terms for investigation, space, Evil, abstracted, and stood. Gavin then produces visualized conceptual spaces for each of those four terms, for the four terms together, and for the entire passage.

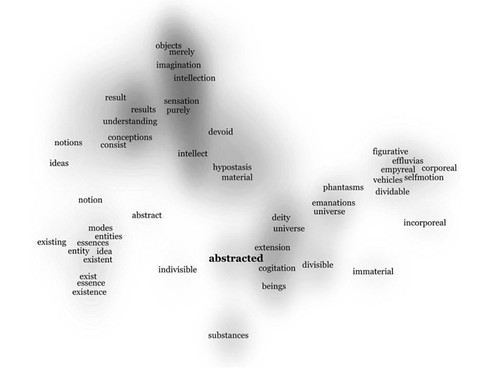

Let’s first consider the space for abstracted:

Gavin notes: “abstracted connects to highly specialized vocabularies for ontology (entity, essence, existence), epistemology (imagination, sensation), and physics (selfmotion)...” (p. 668).

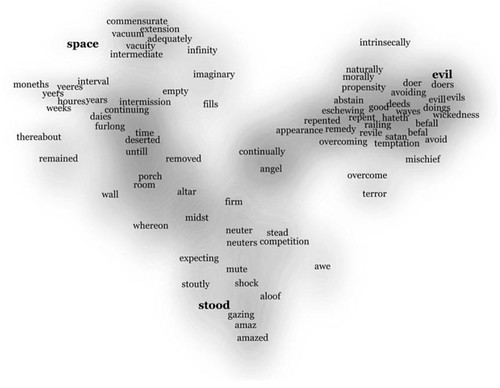

Here’s the space for the four words taken together as a composite vector:

Notice that space, evil, and stood are set in bold type and collocates of each appear in this compound space. But neither abstracted nor any of its collocates appears. As Gavin noted to me in a tweet, “Abstracted is abstracted away. It’s in there in the data, but it’s just too idiosyncratic for its collocates to float to the top” [5]. I note that one edition of Paradise Lost glosses abstracted as withdrawn. That’s apt enough, I suppose, but misses the metaphysical and, well, abstract meanings of the word [6]. Withdrawn could be a mere matter of physical location, but there’s much more than that at stake. As Gavin notes (671-672):

The space of evil is a space of action, of doings and deeds, of eschewing and overcoming, while Satan at this moment occupies a very different kind of space, one characterized by abstract spatiotemporal dimensionality more appropriate to angels, an emptiness visible only as an absence of action and volition.

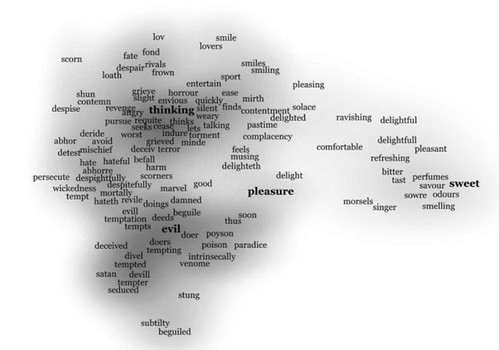

Notice angel at the center of the diagram. Now consider this visualization based on a composite vector of the entire passage:

Notice that Gavin has emphasized thinking, evil, pleasure, and sweet by setting them in boldface type. Notice how those first two are placed within the passage itself:

1) Such Pleasure took the Serpent to behold

2) This Flourie Plat, the sweet recess of Eve

3) Thus earlie, thus alone; her Heav’nly forme

4) Angelic, but more soft, and Feminine,

5) Her graceful Innocence, her every Aire

6) Of gesture or lest action overawd

7) His Malice, and with rapine sweet bereav’d

8) His fierceness of the fierce intent it brought:

9) That space the Evil one abstracted stood

10) From his own evil, and for the time remaind

11) Stupidly good, of enmity disarm’d,

12) Of guile, of hate, of envie, of revenge;

13) But the hot Hell that alwayes in him burnes,

14) Though in mid Heav’n, soon ended his delight,

15) And tortures him now more, the more he sees

16) Of pleasure not for him ordain’d: then soon

17) Fierce hate he recollects, and all his thoughts

18) Of mischief, gratulating, thus excites.

The passage begins (line 1) and ends (16) with pleasure while evil appears in the pair of middle lines (9 and 10). Notice, furthermore, that the passage moves through sweet twice on the way from pleasure in line one to evil in line nine while thoughts (rather than thinking) occurs in the second half of the passage in the line after pleasure in line 16. And of course, the mood has changed from the beginning to the end. In the beginning the pleasure seems pure but at the end it is attended by the knowledge that it is unavailable.

I don’t know quite what to make of that. But just what do I mean by “that”? On the one hand Gavin’s analytic method is inherently spatial, revealing a geometry of meaning, albeit a geometry in a high dimensional space. This eighteen line passage is characterized by a subspace in which four terms are prominent: thinking, evil, pleasure, sweet. Those four terms are co-present in that subspace.

In the poem itself, however, those four terms appear in sequence, and in a sequence that has an interesting order. Two of them form a chiasmus that is centered on abstracted: pleasure...evil...abstracted... evil... pleasure. We could diagram the path like this:

THAT’s how I think about that passage, as a path through semantic space [7]. However, if we’re going start thinking about paths, then we need to add another loop for sweet, which also occurs twice. Now we have:

Now we’ve lost our symmetry, which is neither here not there. If that’s that path, then that’s the path.

Texts as paths in semantic space

But I’m only eyeballing these paths using selected words. I note, however, that I probably would not have placed abstracted at the center if I didn’t have Gavin’s model before me. What else would a vector semantics model reveal that is invisible to more informal methods?

One could, in principle, construct a complete path for that passage and do so algorithmically. What would that path look like? Better yet, let’s do it for the entire poem. What would THAT look like?

I haven’t the foggiest idea. But I’d like to so. Why would I like to see? Because that’s how I think about texts, literary and every other kind of text, as a path generated through semantic space. As I have explained many times over, I studied computational semantics early in my career and learned to think of texts as paths through semantic networks [8]. Why not take such an approach to vector semantics something I’ve explored in a working paper [9]? Will there be methodological issues, tough ones? Of course. Aren’t there always?

Consider this passage from that working paper on virtual reading:

...the structuralists have proposed that texts are constructed over patterns of binary oppositions. When we examine the trajectories for different texts, can we identify opposed regions of semantic space [...]? What happens if we reduce the dimensionality of a space by treating binary oppositions as the poles along a single dimension? [...] What about one of my current hobby-horses, ring-composition? It has been my experience that identifying ring-composition is not easy. Ring-form texts do not have obvious markers. More often than not I identified a given text as ring-form only after I had been working on it for a while, in some cases quite awhile. Perhaps ring-composition would show up in the trajectory of a virtual reading.

Keep in mind that we’re talking about the human mind, about mapping the mind. Those paths are traces of the mind in motion. It’s one thing to map the brain. But the mind? That’s not been done before, not to my knowledge. Can there be any greater intellectual adventure that at long last beginning to map the mind?

Notes and References

[1] Michael Gavin, Vector Semantics, William Empson, and the Study of Ambiguity, Critical Inquiry 44 (Summer 2018) 641-673: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/698174. Ungated PDF: http://modelingliteraryhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Gavin-2018-Vector-Semantics.pdf

[2] Magnus Sahlgren, The Word-Space Model: Using Analysis to Represent Syntagmatic and Paradigmatic Relations between Words in High-Dimensional Vector Spaces (PhD. diss. Stock- holm University, 2006), p. 27, eprints.sics.se/437/1/TheWordSpaceModel.pdf

[3] The examples are from Ekaterina Vylomova, Laura Rimell, Trevor Cohn, Timothy Baldwin, Take and Took, Gaggle and Goose, Book and Read: Evaluating the Utility of Vector Differences for Lexical Relation Learning, 13 August 2016 arXiv:1509.01692v4 [cs.CL].

[4] Derek Attridge and Henry Staten, The Craft of Poetry: Dialogues on Minimal Interpretation, Routledge 2015.

[5] Michael Gavin on Twitter, https://twitter.com/Michael_A_Gavin/status/1007691837228945408

[6] I wonder what would happen if Gavin were to perform his analysis as though withdrawn were the word Milton had used. I suspect that both withdrawn and some of its collocates would appear in the snapshot of the four words taken together.

[7] I’d asked Michael about the words he set in bold in that figure:

You’ve bolded four words in this figure. You’ve commented on thinking and evil in your text, but not the other two. What did you have in mind in bolding sweet and pleasure? Both of those words occur twice in the passage, which interests me, as does evil.He replied:

In an earlier draft I talked about "pleasure" as a concept in the passage, but also over EEBO [Early English Books Online] as a whole. The term is interesting because it has meanings that can be teased apart -- pleasure was often used in the sense of command or authority, as in "the pleasure of the king" and there was a time when working on this that I planned to extend the conceptual analysis out further. Mostly, though, I just highlighted those words because I thought doing so made the graph easier to read, because those were the simplest, most immediately graspable terms. A more rigorous method could be devised, I'm sure.[8] William Benzon. Cognitive Networks and Literary Semantics. MLN 91: 952-982, 1976: https://www.academia.edu/235111/Cognitive_Networks_and_Literary_Semantics. [9] William Benzon, Virtual Reading: The Prospero Project Redux, Working Paper, Version 2, October 2018, 38 pp, Academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/34551243/Virtual_Reading_The_Prospero_Project_Redux; SSRN, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3036076.

No comments:

Post a Comment