Or, Center Point construction in a tale within a tale within a tale

For Mary Douglas

It’s a long way through this post. First, I look at the structural center of Heart of Darkness, which is that long paragraph I’ve called the nexus. I then argue that Heart and Osamu Tezuka’s Metropolis deploy different techniques for achieving what I’m calling center point construction, which is close kin to the ring forms that held Mary Douglas’s attention at the end of her career. Finally, I attach an appendix that contains the complete text of the nexus.

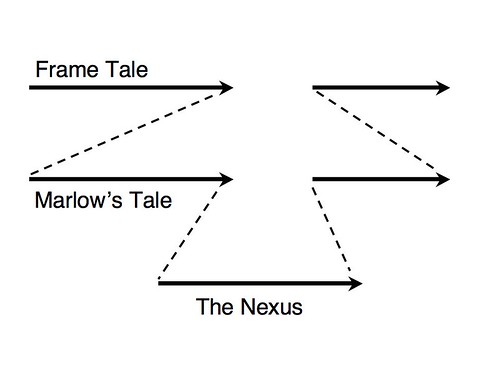

Consider the following diagram. It represents, albeit crudely, the narrative structure of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness:

While the tale is told mostly by Marlow, Marlow does not speak directly to us, the readers. Rather, his tale is told to a group of four men aboard a boat in the Thames. One of those tells it to us. That tale is the frame tale. It begins Conrad’s novella, running for roughly 1300 words before giving way to Marlow, and it concludes the novella, with the last 70 words or so. It also shows up here and there during Marlow’s tale, though never for long. The diagram doesn’t show those . . . what shall we call them, intrusions, reminders, touchstones relief points?

This much is well-recognized in the literature on the book, which I’ve been examining in the two case books I’ve just acquired, the Norton Critical Edition (2006) edited by Paul Armstrong, and Ross C. Murfin’s Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2011). But there’s a third ‘level’, which I’m calling the nexus. It is not, in what I’ve read so far, singled out as a tale within the tale within the tale, as my diagram has it.

But it is certainly mentioned. For example, in Albert Guerard’s, “The Journey Within” (from his 1958 book, Conrad the Novelist), which is reprinted in the Norton, pp. 326-336. He says, “We think we are about to meet Kurtz at last,” referring to a passage in paragraph 101 (see endnote on paragraph numbering) where Marlow tells us that he did get to meet Kurtz. And then Guerard observes: “But instead Marlow leaps ahead to his meeting with the “Intended”; comments on Kurtz’s megalomania and assumption of his place among the devils of the land; reports on his seventeen-page pamphlet ...” In those three clauses Guerard has characterized the paragraph that I’m calling the nexus.

The Nexus

The segment I’m calling the nexus is part of Marlow’s tale, but I believe that it deserves to be treated as a separate narrative entity. For one thing, and this is what originally brought it to my attention, it contains material that is told out of temporal order. At the point where Marlow launches into the nexus – which, by the way, is one of the places where the frame tale reaches in to Marlow’s tale, reminding us that Marlow is not talking to us, but that he’s talking to someone else, and it is this anonymous someone else who writes to us – they have not yet gotten to the Inner Station, where Marlow is located. And yet it is during the nexus that Marlow tells us, not simply of all the ivory they found and recovered at the station, but that they loaded it aboard the ship: “We filled the steamboat with it, and had to pile a lot on the deck.” That ivory is not mentioned later at the time when they actually do load it into the boat. In paragraph 140 it’s the middle of the night and Marlow has followed Kurtz ashore and then in paragraph 141 we’ve left at noon and nothing is said about carting 1000s of pounds of ivory onto the ship.

What’s going on in the story at the point where the nexus emerges is that the boat is a few hours away from the Inner Station and is under attack. The helmsman has just been killed and Marlow, who was captaining the boat, was standing in the man’s blood. He, Marlow, tossed a blood-drenched shoe overboard and had told himself that, alas, he would never hear Marlow speak:

I made the strange discovery that I had never imagined him as doing, you know, but as discoursing. I didn't say to myself, 'Now I will never see him,' or 'Now I will never shake him by the hand,' but, 'Now I will never hear him.' The man presented himself as a voice. Not of course that I did not connect him with some sort of action.

Then the other shoe

went flying unto the devil-god of that river. I thought, 'By Jove! it's all over. We are too late; he has vanished—the gift has vanished, by means of some spear, arrow, or club. I will never hear that chap speak after all,'—and my sorrow had a startling extravagance of emotion, even such as I had noticed in the howling sorrow of these savages in the bush.

At which point the teller of the frame tale takes over for a bit, describing Marlow lighting and taking a draw on his pipe, and, after some preparatory chatter from Marlow (paragraph 101) and a long silence – what was going on in Marlow’s mind during that silence? – then, and only then, do we get the nexus.

Think about it: Conrad didn’t toss both shoes overboard at once. He tossed one, then threw out a significant thought, and then tossed the other. That’s a very careful, very particular bit of writing. Why make such a big deal out of Marlow’s bloody shoes? Because it’s in our shoes that we trod the earth, because Oedipus means swollen-footed? I don’t know, but Conrad did make a deal out of it. At this critical point in the story where a man, an African, died.

But I digress. The nexus. So, Marlow tosses his shoes overboard, then relieves himself of the nexus, 1500 words in a story of 38,000 words, for 4% of the total. And then he returns his telling to the story’s present and drags the lifeless body over the edge:

The current snatched him as though he had been a wisp of grass, and I saw the body roll over twice before I lost sight of it for ever. All the pilgrims and the manager were then congregated on the awning-deck about the pilot-house, chattering at each other like a flock of excited magpies, and there was a scandalized murmur at my heartless promptitude. What they wanted to keep that body hanging about for I can't guess. Embalm it, maybe.

Other than Kurtz, this is the only other person who dies in the story. That Conrad should tuck the novella’s longest paragraph into the moments between shoes overboard and corpse overboard is no accident, nor is it an accident that this paragraph contains out-of-sequence information.

Those three things – out of sequence information, the helmsman’s death, and the length of the paragraph – all suggest to me that this paragraph is special, that it deserves to be treated as a separate ‘level’ of narration. Technically, no, it’s not a tale within a tale. Effectively, it is, giving us the structure I’ve diagrammed above.

What’s it About?

So what’s in this paragraph that I call it the nexus? [Note that I’ve copied the whole paragraph into an appendix to this post.] It begins by asserting that this world, the world of the tale, is men only:

Girl! What? Did I mention a girl? Oh, she is out of it--completely. They--the women, I mean--are out of it--should be out of it. We must help them to stay in that beautiful world of their own, lest ours gets worse. Oh, she had to be out of it. You should have heard the disinterred body of Mr. Kurtz saying, 'My Intended.' You would have perceived directly then how completely she was out of it.

Yes, women are out of it but specifically, the Intended. This is the first time she’s mentioned as such, the first time we know that Kurtz intended to get married. But we don’t actually see her until the very end of the story.

From there Marlow works his way quickly to the ivory by way of Kurtz’s bald head, “like a ball—an ivory ball.” Then there’s talk of the moral comforts and pressure of home, which are gone in the jungle, Kurtz’s pan-European background, his education, his beautifully-written report to the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs, the unspeakable practices Kurtz allowed himself, and, of course, the report’s postscript: “Exterminate all the brutes!” And by the by Marlow arrives at something of an abbreviated eulogy for his helmsman:

I missed my late helmsman awfully,--I missed him even while his body was still lying in the pilot-house. Perhaps you will think it passing strange this regret for a savage who was no more account than a grain of sand in a black Sahara. Well, don't you see, he had done something, he had steered; for months I had him at my back--a help--an instrument. It was a kind of partnership. He steered for me--I had to look after him, I worried about his deficiencies, and thus a subtle bond had been created, of which I only became aware when it was suddenly broken. And the intimate profundity of that look he gave me when he received his hurt remains to this day in my memory--like a claim of distant kinship affirmed in a supreme moment.

That ends it, the nexus.

And it call it that because, whatever this story’s about, it’s all there, compressed into those 1500 words. It’s a part that is also the image of the whole. And within that part we have the Litany — 'My Intended, my ivory, my station, my river, my—' which, in its way, is a highly compressed image of the whole. We thus have THE WHOLE STORY compressed into THE NEXUS compressed into THE LITANY.

Note, finally, that the nexus begins by mentioning the Intended, and then pushing her aside, and ends with Marlow’s eulogy for his helmsman. If there’s any heart in this story, that’s it, Marlow’s feeling for his lost helmsman – is it an accident that Conrad made this man a helmsman, the one who steered the boat? I’m reminded of that other great 19th Century river yarn, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. A very different yarn, to be sure, but one built on the bond between a white man, in the person of Huck Finn, abused son of an alcoholic, and a black man, Jim, runaway slave. The bond between Huck and Jim was real, but far from simple. In particular, it did not prevent Huck from allowing Tom Sawyer to stage an elaborate play with Jim in the center, a play that had more to do with Tom’s theatricality than Jim’s desire for freedom. Similarly, I do not think we have to believe that Marlow (and Conrad) regarded the helmsman’s humanity as being equal to his own in order to credit his feeling for the man, a man who is nameless, like everyone else in this tale except Kurtz.

Center Point Construction

And THAT is my best guess as to why Conrad stuck the nexus, with its out-of-sequence material, at this point in the narrative. For reasons having to do with a psychology we don’t understand, the nexus had to be toward the center of the book. Whatever effect Conrad was after, it required that the nexus be in more or less this place. Too early and we wouldn’t know enough, or not know enough, to appreciate it; too late and, well, it would be too late. It had to go toward the middle. Given that the ivory is at the material center of this greedy activity, the nexus had to assure us that, yes, the ivory was safely in hand, even though we hadn’t gotten to that point in the story.

For it isn’t in the center. Heart of Darkness was broken into three installments for serial publication. The nexus is in the second half of the middle installment. The whole text is something over 38,000 words long. The nexus starts at about 23,000 words in and there are roughly 13,500 words after it. So it’s well beyond the center, but not quite in the last third.

Now, when I first spotted the temporal displacement, I thought of ring form. Why? Because the last time I spotted such a displacement it was in Osamu Tezuka’s manga (graphic novel), Metropolis, which turned out, upon examination, to have a ring form (Benzon 2006). Am I thus in the process of arguing that Heart of Darkness is a ring form?

That depends on what one means by ring form. Consider this simple tale:

1) Mary leaves home.

2) She walks past the oak tree.

3) She walks past the post box.

4) She arrives at the grocery store.

5) She opens the door and enters.

6) She nods to the cashier.

7) She gets a bottle of milk from the cooler.

6’) She pays the cashier for the milk.

5’) She exits through the door.

4’) She walks away from the grocery store.

3’) She walks past the post box.

2’) She walks past the oak tree.

1’) Mary arrives home.

That’s what we can call a canonical ring form, with the departure from arrival back home being the first and last elements in the ring and the purchase of the bottle of milk being the mid-point. The events in the tale are arrayed symmetrically about the mid-point.

In Thinking in Circles (pp. 18-26), Mary Douglas argues that the binding of Isaac, Genesis 22.1-18, is a canonical ring. Metropolis, and I did not, alas, mention this in my essay, is not a canonical ring. If not a canonical ring, then what kind of ring? Here’s the structure:

1) Prelude (frame)

2) Greater Metropolis

3) Underground

4) Child's World

5) Revelations

4’) Child's World

3’) Underground

2’) Greater Metropolis

1') Coda (frame)

The ring form is constituted, not by specific events being mirrored before and after the midpoint, but in the way the action moves through various distinctly different realms of action. There is a frame, which is presided over by a fellow with a Charles-Darwin beard who discourses about evolution. Then there is the city at large (Greater Metropolis), an underground world run by criminals (Underground), a school, school yard and a home where we follow the actions of children (Child’s World), and, at the center of it all, Revelations. The last is where we learn, first of all, the ‘secret’ of the central character’s being, and we learn of strange things happening all over the world. The whole story pretty much revolves on what’s revealed in that central section.

And that IS consistent with Douglas’s characterization of the midpoint in ring forms, which is fifth in her list seven characteristics of ring form (p. 37): “Central loading: The turning point of the ring is equivalent to the middle term, C, that is the middle term of a chiasmus, AB / C / BA. Consequently, much of the rest of the structure depends on a well-marked turning point that should be unmistakable.” The structural center of Metropolis is strongly marked by the reading of a hidden and long-sought document while the structural center of Heart of Darkness is marked by various features I’ve described above: the death of the helmsman, shoes overboard, the intervention of the top-level narrative, Marlow’s long silence, and the unexpected mention of the Intended.

This strong central loading, along with the ‘non-canonical’ rings, gives Metropolis and Heart of Darkness a deep formal similarity to canonical rings. They exhibit what I’m provisionally calling center point construction. The canonical ring is one way of achieving center point construction. Conrad used a different method in Heart of Darkness while Tezuka use yet a different method in Metropolis.

Are there other methods of achieving center point construction? And, what’s the point of it? Why would an author employ it? Those questions, obviously, are well beyond the scope of a post that is, after all, about one specific text that uses the technique.

* * * * *

William Benzon. Tezuka’s Metropolis: A Modern Japanese Fable about Art and the Cosmos. In Uta Klein, Ktaja Mellmann, Steffanie Metzger, eds. Heurisiken der Literaturwissenschaft: Disciplinexterne Perspektiven auf Literatur. mentis Verlag GmbH, 2006, pp. 527-545.

Mary Douglas, Thinking in Circles: An Essay on Ring Composition. Yale UP. 2007.

* * * * *

Paragraph numbering: I’m using the Project Gutenberg text, which you will find here: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/526

I’ve numbered the paragraphs sequentially from first to last, which is numbered 198. Alas, the file has no editorial information about the source text so it’s possible that this numbering won’t apply to all editions.

Earlier posts in this series:

- Heart of Darkness, Narration and Temporal Displacement

- Interlude: Slocum’s Pilot and Sensory Deprivation

- Closure, Attachment, and Abstract Objects in Heart of Darkness

- Ontology at the Heart of Darkness

Appendix: The Nexus Text

Here’s the nexus in full. I’ve provided a few paragraphs before the nexus, which I’ve called the Lead-in and a few paragraphs after, which I’ve called the Follow-on. I’ve numbered the paragraphs as though from the beginning of the text. As I explained in the main text, the nexus is inserted into the story at the conclusion of an attack on the steamboat. The helmsman is killed and Marlow’s shoes are covered in blood. The Lead-in starts with the second shoe going overboard. The Follow-on ends in the paragraph where Kurtz’s compound is finally spotted.

* * * * *

The Lead-in

[99] "The other shoe went flying unto the devil-god of that river. I thought, 'By Jove! it's all over. We are too late; he has vanished—the gift has vanished, by means of some spear, arrow, or club. I will never hear that chap speak after all,'—and my sorrow had a startling extravagance of emotion, even such as I had noticed in the howling sorrow of these savages in the bush. I couldn't have felt more of lonely desolation somehow, had I been robbed of a belief or had missed my destiny in life. . . . Why do you sigh in this beastly way, somebody? Absurd? Well, absurd. Good Lord! mustn't a man ever—Here, give me some tobacco." ...

[100] There was a pause of profound stillness, then a match flared, and Marlow's lean face appeared, worn, hollow, with downward folds and dropped eyelids, with an aspect of concentrated attention; and as he took vigorous draws at his pipe, it seemed to retreat and advance out of the night in the regular flicker of the tiny flame. The match went out.

[101] "Absurd!" he cried. "This is the worst of trying to tell. ... Here you all are, each moored with two good addresses, like a hulk with two anchors, a butcher round one corner, a policeman round another, excellent appetites, and temperature normal—you hear—normal from year's end to year's end. And you say, Absurd! Absurd be—exploded! Absurd! My dear boys, what can you expect from a man who out of sheer nervousness had just flung overboard a pair of new shoes. Now I think of it, it is amazing I did not shed tears. I am, upon the whole, proud of my fortitude. I was cut to the quick at the idea of having lost the inestimable privilege of listening to the gifted Kurtz. Of course I was wrong. The privilege was waiting for me. Oh yes, I heard more than enough. And I was right, too. A voice. He was very little more than a voice. And I heard—him—it—this voice—other voices—all of them were so little more than voices—and the memory of that time itself lingers around me, impalpable, like a dying vibration of one immense jabber, silly, atrocious, sordid, savage, or simply mean, without any kind of sense. Voices, voices—even the girl herself—now—"

[102] He was silent for a long time.

The Nexus

[103] "I laid the ghost of his gifts at last with a lie," he began suddenly. "Girl! What? Did I mention a girl? Oh, she is out of it—completely. They—the women, I mean—are out of it—should be out of it. We must help them to stay in that beautiful world of their own, lest ours gets worse. Oh, she had to be out of it. You should have heard the disinterred body of Mr. Kurtz saying, 'My Intended.' You would have perceived directly then how completely she was out of it. And the lofty frontal bone of Mr. Kurtz! They say the hair goes on growing sometimes, but this—ah specimen, was impressively bald. The wilderness had patted him on the head, and, behold, it was like a ball—an ivory ball; it had caressed him, and—lo!—he had withered; it had taken him, loved him, embraced him, got into his veins, consumed his flesh, and sealed his soul to its own by the inconceivable ceremonies of some devilish initiation. He was its spoiled and pampered favorite. Ivory? I should think so. Heaps of it, stacks of it. The old mud shanty was bursting with it. You would think there was not a single tusk left either above or below the ground in the whole country. 'Mostly fossil,' the manager had remarked disparagingly. It was no more fossil than I am; but they call it fossil when it is dug up. It appears these niggers do bury the tusks sometimes—but evidently they couldn't bury this parcel deep enough to save the gifted Mr. Kurtz from his fate. We filled the steamboat with it, and had to pile a lot on the deck. Thus he could see and enjoy as long as he could see, because the appreciation of this favor had remained with him to the last. You should have heard him say, 'My ivory.' Oh yes, I heard him. 'My Intended, my ivory, my station, my river, my—' everything belonged to him. It made me hold my breath in expectation of hearing the wilderness burst into a prodigious peal of laughter that would shake the fixed stars in their places. Everything belonged to him—but that was a trifle. The thing was to know what he belonged to, how many powers of darkness claimed him for their own. That was the reflection that made you creepy all over. It was impossible—it was not good for one either—trying to imagine. He had taken a high seat amongst the devils of the land—I mean literally. You can't understand. How could you?—with solid pavement under your feet, surrounded by kind neighbors ready to cheer you or to fall on you, stepping delicately between the butcher and the policeman, in the holy terror of scandal and gallows and lunatic asylums—how can you imagine what particular region of the first ages a man's untrammeled feet may take him into by the way of solitude—utter solitude without a policeman—by the way of silence, utter silence, where no warning voice of a kind neighbor can be heard whispering of public opinion? These little things make all the great difference. When they are gone you must fall back upon your own innate strength, upon your own capacity for faithfulness. Of course you may be too much of a fool to go wrong—too dull even to know you are being assaulted by the powers of darkness. I take it, no fool ever made a bargain for his soul with the devil: the fool is too much of a fool, or the devil too much of a devil—I don't know which. Or you may be such a thunderingly exalted creature as to be altogether deaf and blind to anything but heavenly sights and sounds. Then the earth for you is only a standing place—and whether to be like this is your loss or your gain I won't pretend to say. But most of us are neither one nor the other. The earth for us is a place to live in, where we must put up with sights, with sounds, with smells too, by Jove!—breathe dead hippo, so to speak, and not be contaminated. And there, don't you see? Your strength comes in, the faith in your ability for the digging of unostentatious holes to bury the stuff in—your power of devotion, not to yourself, but to an obscure, back-breaking business. And that's difficult enough. Mind, I am not trying to excuse or even explain—I am trying to account to myself for—for—Mr. Kurtz—for the shade of Mr. Kurtz. This initiated wraith from the back of Nowhere honored me with its amazing confidence before it vanished altogether. This was because it could speak English to me. The original Kurtz had been educated partly in England, and—as he was good enough to say himself—his sympathies were in the right place. His mother was half-English, his father was half-French. All Europe contributed to the making of Kurtz; and by-and-by I learned that, most appropriately, the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs had intrusted him with the making of a report, for its future guidance. And he had written it too. I've seen it. I've read it. It was eloquent, vibrating with eloquence, but too high-strung, I think. Seventeen pages of close writing he had found time for! But this must have been before his—let us say—nerves, went wrong, and caused him to preside at certain midnight dances ending with unspeakable rites, which—as far as I reluctantly gathered from what I heard at various times—were offered up to him—do you understand?—to Mr. Kurtz himself. But it was a beautiful piece of writing. The opening paragraph, however, in the light of later information, strikes me now as ominous. He began with the argument that we whites, from the point of development we had arrived at, 'must necessarily appear to them [savages] in the nature of supernatural beings—we approach them with the might as of a deity,' and so on, and so on. 'By the simple exercise of our will we can exert a power for good practically unbounded,' &c., &c. From that point he soared and took me with him. The peroration was magnificent, though difficult to remember, you know. It gave me the notion of an exotic Immensity ruled by an august Benevolence. It made me tingle with enthusiasm. This was the unbounded power of eloquence—of words—of burning noble words. There were no practical hints to interrupt the magic current of phrases, unless a kind of note at the foot of the last page, scrawled evidently much later, in an unsteady hand, may be regarded as the exposition of a method. It was very simple, and at the end of that moving appeal to every altruistic sentiment it blazed at you, luminous and terrifying, like a flash of lightning in a serene sky: 'Exterminate all the brutes!' The curious part was that he had apparently forgotten all about that valuable postscriptum, because, later on, when he in a sense came to himself, he repeatedly entreated me to take good care of 'my pamphlet' (he called it), as it was sure to have in the future a good influence upon his career. I had full information about all these things, and, besides, as it turned out, I was to have the care of his memory. I've done enough for it to give me the indisputable right to lay it, if I choose, for an everlasting rest in the dust-bin of progress, amongst all the sweepings and, figuratively speaking, all the dead cats of civilization. But then, you see, I can't choose. He won't be forgotten. Whatever he was, he was not common. He had the power to charm or frighten rudimentary souls into an aggravated witch-dance in his honor; he could also fill the small souls of the pilgrims with bitter misgivings: he had one devoted friend at least, and he had conquered one soul in the world that was neither rudimentary nor tainted with self-seeking. No; I can't forget him, though I am not prepared to affirm the fellow was exactly worth the life we lost in getting to him. I missed my late helmsman awfully,—I missed him even while his body was still lying in the pilot-house. Perhaps you will think it passing strange this regret for a savage who was no more account than a grain of sand in a black Sahara. Well, don't you see, he had done something, he had steered; for months I had him at my back—a help—an instrument. It was a kind of partnership. He steered for me—I had to look after him, I worried about his deficiencies, and thus a subtle bond had been created, of which I only became aware when it was suddenly broken. And the intimate profundity of that look he gave me when he received his hurt remains to this day in my memory—like a claim of distant kinship affirmed in a supreme moment.

The Follow-on

[104] "Poor fool! If he had only left that shutter alone. He had no restraint, no restraint—just like Kurtz—a tree swayed by the wind. As soon as I had put on a dry pair of slippers, I dragged him out, after first jerking the spear out of his side, which operation I confess I performed with my eyes shut tight. His heels leaped together over the little door-step; his shoulders were pressed to my breast; I hugged him from behind desperately. Oh! he was heavy, heavy; heavier than any man on earth, I should imagine. Then without more ado I tipped him overboard. The current snatched him as though he had been a wisp of grass, and I saw the body roll over twice before I lost sight of it for ever. All the pilgrims and the manager were then congregated on the awning-deck about the pilot-house, chattering at each other like a flock of excited magpies, and there was a scandalized murmur at my heartless promptitude. What they wanted to keep that body hanging about for I can't guess. Embalm it, maybe. But I had also heard another, and a very ominous, murmur on the deck below. My friends the wood-cutters were likewise scandalized, and with a better show of reason—though I admit that the reason itself was quite inadmissible. Oh, quite! I had made up my mind that if my late helmsman was to be eaten, the fishes alone should have him. He had been a very second-rate helmsman while alive, but now he was dead he might have become a first-class temptation, and possibly cause some startling trouble. Besides, I was anxious to take the wheel, the man in pink pyjamas showing himself a hopeless duffer at the business.

[105] "This I did directly the simple funeral was over. We were going half-speed, keeping right in the middle of the stream, and I listened to the talk about me. They had given up Kurtz, they had given up the station; Kurtz was dead, and the station had been burnt—and so on—and so on. The red-haired pilgrim was beside himself with the thought that at least this poor Kurtz had been properly revenged. 'Say! We must have made a glorious slaughter of them in the bush. Eh? What do you think? Say?' He positively danced, the bloodthirsty little gingery beggar. And he had nearly fainted when he saw the wounded man! I could not help saying, 'You made a glorious lot of smoke, anyhow.' I had seen, from the way the tops of the bushes rustled and flew, that almost all the shots had gone too high. You can't hit anything unless you take aim and fire from the shoulder; but these chaps fired from the hip with their eyes shut. The retreat, I maintained—and I was right—was caused by the screeching of the steam-whistle. Upon this they forgot Kurtz, and began to howl at me with indignant protests.

[106] "The manager stood by the wheel murmuring confidentially about the necessity of getting well away down the river before dark at all events, when I saw in the distance a clearing on the river-side and the outlines of some sort of building. 'What's this?' I asked. He clapped his hands in wonder. 'The station!' he cried. I edged in at once, still going half-speed.

[107] "Through my glasses I saw the slope of a hill interspersed with rare trees and perfectly free from undergrowth. A long decaying building on the summit was half buried in the high grass; the large holes in the peaked roof gaped black from afar; the jungle and the woods made a background. There was no inclosure or fence of any kind; but there had been one apparently, for near the house half-a-dozen slim posts remained in a row, roughly trimmed, and with their upper ends ornamented with round carved balls. The rails, or whatever there had been between, had disappeared. Of course the forest surrounded all that. The river-bank was clear, and on the water-side I saw a white man under a hat like a cart-wheel beckoning persistently with his whole arm. Examining the edge of the forest above and below, I was almost certain I could see movements—human forms gliding here and there. I steamed past prudently, then stopped the engines and let her drift down. The man on the shore began to shout, urging us to land. 'We have been attacked,' screamed the manager. 'I know—I know. It's all right,' yelled back the other, as cheerful as you please. 'Come along. It's all right. I am glad.'

No comments:

Post a Comment