From three years ago (Jan 2015).

I’ve been thinking about writing a guide to my work in literary and cultural criticism, but there’s so much of it that that has seemed to be no simple task. I could list the pieces, but what use is that? And in any event, you can find that on my most recent CV. But I’ve decided to take a step in that direction by addressing an open letter to one of my teachers back at Johns Hopkins, J. Hillis Miller.

That gives me a fairly specific audience. It’s much easier to address a specific audience, with known interests, than to address the General and Undefined Other. I certainly don’t know Miller’s criticism in any detail, but I’ve read several recent pieces and interviews where he talks about the profession in general historical terms. That, plus resonance from ancient days at Hopkins, is enough for me.

For those of you in literary studies, J. Hillis Miller needs no introduction. He is one of the premier English language critics of the last half-century. For those in other disciplines, Miller’s career started at a time when interpreting texts was just becoming accepted in academic literary criticism and he became central in the use of philosophy, broadly understood, in that undertaking.

* * * * *

Dear Prof. Miller:

I’ve been mulling over the wonderful profile of Earl Wasserman that was recently published in the Hopkins Magazine. That got me thinking about the state of the profession, the transit from then to now, and where are we going anyhow? Wasserman, of course, was your colleague and he was my teacher. As it was the "structuralist moment" that ultimately captured my imagination, Wasserman was not so central as Dick Macksey, but he was still very important to me, in part through the exemplary force of his intellectual engagement. I also audited one of your graduate courses (as I recall, Carol Jacobs was a student in that course). I believe you even wrote a graduate school recommendation for me.

The profession used the structuralist moment to go in one direction and I used it to go in a rather different one. On the chance that you might be curious about where I’ve ended up I thought I would write you a letter. FWIW (an abbreviation for a phrase that titled one of the great protest songs of the 60s, “For What It’s Worth”) the open letter is a form I find congenial, having addressed letters to Steven Pinker, Alan Liu, and Willard McCarty.

A Fork in the Road

For the profession the structuralist moment rather quickly gave way to deconstruction, post-structuralism, cultural studies, and various identity-based criticisms, all of which somehow became snarled in a ball that became “Theory.” For me, however, structuralism gave way to cognitive science and that’s what I grafted to literary study at SUNY Buffalo. That English department was as wondrous in its own way as the Hopkins department was in a somewhat different way. One of the small wonders is that it granted me a degree despite the fact that no one in the department was deeply involved with cognitive science (I got that in the Linguistics Department, from a polymath named David Hays).

The profession, alas, was not ready for cognitive science at that time. By the time the profession began coming around to it in the mid-1990s I had come to believe that I had misjudged the significance of cognitive science. As important and interesting as those theories and models were (and still are) I decided that cognitive science had a different message, one that echoes an older one, a Wassermanian message: stick to the text.

It was the text of “Kubla Khan” that sent me to cognitive science in the first place and now cognitive science has sent me back, not simply to “Kubla Khan,” but to any and all texts. They all need to be looked at closely, not necessarily in a New Critical or a phenomenological, or a narratological, or a deconstructive way, but closely, more closely than ever before. I’m told that the kids these days call it surface reading.

Though I’ve been publishing in the formal literature off and on, perhaps your best route into what I’ve discovered would be through a series of informal working papers I’ve recently put online. I’ve spent quite a bit of time blogging over the past several years and, in particular, have specialized in “long-form” posts, posts running 2000 words or more. When I’ve accumulated a set of such posts on one topic I combine them into a single document and then make it available online for downloading.

Such working papers are more coherent than private notes, but not so polished as formal papers. The scholarly apparatus–references, discussions of other work–is a bit thin. And they’re a bit repetitious, for which I will not apologize as skipping over things is easy enough to do.

I’ve selected five working papers:

- Heart of Darkness: Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis on Several Scales (2011, 48 pp.): https://www.academia.edu/8132174/Heart_of_Darkness_Qualitative_and_Quantitative_Analysis_on_Several_Scales

- Apocalypse Now: Working Papers (2011, 51 pp.): https://www.academia.edu/7866632/Myth_From_Lévi-Strauss_and_Douglas_to_Conrad_and_Coppola

- Myth: From Lévi-Strauss and Douglas to Conrad and Coppola (2013, 12 pp.): https://www.academia.edu/7866632/Myth_From_Lévi-Strauss_and_Douglas_to_Conrad_and_Coppola

- Ring Composition: Some Notes on a Particular Literary Morphology (2014, 59 pp): https://www.academia.edu/8529105/Ring_Composition_Some_Notes_on_a_Particular_Literary_Morphology

- Reading Macroanalysis: Notes on the Evolution of Nineteenth Century Anglo-American Literary Culture (2014, 100 pp.): https://www.academia.edu/8183111/Reading_Macroanalysis_Notes_on_the_Evolution_of_Nineteenth_Century_Anglo-American_Literary_Culture

You are of course free to examine them in any order, but there is a reason for that particular order. I start with a set of posts on important text that I know you have written about, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Apocalypse Now is a rather different text in a different medium, but nonetheless intimately related with Heart of Darkness as Coppola kept a copy of Heart with him while shooting his film. Those two working papers each in its way harkens back to my structuralist roots, which come to the fore in the next two working papers. The fourth one (on ring composition) also discusses some poems: Dylan Thomas, “Author’s Prologue”, Coleridge, “Kubla Khan”, and Williams, “To a Solitary Disciple”.

The last working paper, and the longest by far, heads out into conceptual territory which I assume, perhaps mistakenly so, will be strange to you, the “distant reading” division of the so-called digital humanities. One of the things I do in that paper, however, is use Matthew Jockers’ large-scale analysis of a corpus of 3300 19th century English-language novels to make a case for the autonomy of the aesthetic realm. That is to say, I use (someone else’s) computational analysis to make a case for human freedom.

I don’t know what your thoughts are on the use of computers in literary study, but I do know that there are many who believe that they are a harbinger of the Apocalypse, which is what an earlier generation of critics thought about deconstruction and the rest. The sky didn’t fall then and it’s not falling now. But there are accommodations to be made, and they are not always easily accomplished.

Heart of Darkness

In some of your remarks about your career you talk about the importance of accidents. Well, I decided to read Heart of Darkness as a consequence of having immersed myself in Apocalypse Now, which we’ll get to in a bit. Once I’d been working on Heart of Darkness for a while I more or less stumbled into making this chart:

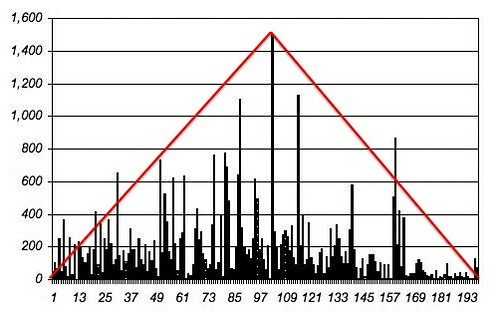

Each bar in the chart represents one paragraph in the text (the electronic version available from Project Gutenberg). The bars take the paragraphs in order from first to last, left to right. The length of a bar is proportional to the length of a paragraph. While the lengths vary wildly, there seems to be a shape to the distribution, which I’ve indicated by those red lines.

Is that shape real? If so, what is its significance and how did it come about? Did Conrad intend the text to be that way? Old questions, no?

I didn’t arrive at those questions and that chart through any prior interest in paragraph length. I got there because I’d become interested in one extraordinary paragraph. Until this particular paragraph Kurtz was little more than an enigma attached to a name. This paragraph gives us his history and some of his thoughts about the future. But that’s not what attracted me to it. What attracted me is that the paragraph contains proleptic elements, the only one in the text to do so. At this point in the narrative we’ve not yet arrived at Kurtz’s compound, but that paragraph contains hints of what we’re going to find there. So I was on the trail of a difference between story and plot: Russian Formalism, narratology.

Moreover, this paragraph is framed in an extraordinary way. Just before Marlow speaks this paragraph he tells us that his helmsman got speared and dropped bleeding to the deck. Just after this paragraph Marlow tells us of pushing the dead man off the deck and into the Congo. So Conrad inserts Kurtz’s story into the moments when the helmsman bleeds out on the deck.

What an extraordinary thing to do.

Well, as I was examining that paragraph, I couldn’t help but notice how very long it was. It seemed that it was the longest in the text by far. Since I had a digital text I decided, on a whim, to use MSWord’s count function to count the number words in each paragraph. It was tedious and took awhile – though not even remotely comparable to the tedium of constructing a concordance using 3 by 5 cards – but it was easy enough to do.

Once I’d done it I ran off that chart to see the results. Sure enough, that extraordinary paragraph was the longest one in the text, and by a considerable margin That’s it, at the peak of the pyramid. It was just over 1500 words long while the next two longest paragraphs weren’t even 1200 words long.

Given what’s actually said in that paragraph and its immediate context, I find it hard to believe that its length was an accident. I also find it hard to believe that Conrad was counting words. However, I have no trouble at all believing that he wanted to create some suspense by dropping the helmsman to the deck and then leaving him there while going on a grand digression. Laurence Sterne did that sort of thing some years earlier.

In that chart, it seems to me, we’re looking at the trace of a mental act, a trace we don’t know how to explain. It’s also a trace we don’t know how to convert into meaning through any of the usual conceptual tools. Maybe we need some new tools? Perhaps a different set of questions?

FWIW, I reported that chart to Mark Liberman at Language Log, a group log of linguists, because I wanted to see if linguists had done any work on paragraph length. He went to work on Nostromo and The Golden Bowl, a rather different text by one of Conrad's contemporaries, and reported the results in a post, Markov's Heart of Darkness. This occasioned a fair bit of discussion about paragraphing. I found it interesting and concluded, provisionally, that no one knew much about paragraphing.

In one section of that working paper I write a commentary on that paragraph. I quote the paragraph in full and insert observations into the text. I’m not looking for anything deep in those observations. I just note what’s there and establish links to other parts of the text.

Marlow’s tale of his trip up the Congo is, of course, embedded in a frame tale, set on the deck of a yacht in the Thames. If we think of that one very long and very strongly marked paragraph as a tale within the tale, that gives us a tale (Kurtz’s history in that paragraph), within a tale (Marlow’s trip), within a tale (the frame story). On that basis I argue that Heart of Darkness exhibits a loose version of ring-form composition, a topic that made its way into PMLA in 1976, where I noted it and set it aside, and that occupied the late Mary Douglas during the last decade or so of her career. I’d begun corresponding with her after she’d blurbed my book on music (Beethoven’s Anvil) and she asked me whether I had any idea of how the brain would do that. That set me on the trail of ring-composition, but I’ll get to that later.

There’s a good deal more in that working paper–a bit of Latour, some attachment theory (which I learned from Mary Ainsworth at Hopkins), a discussion of Achebe in relation to Ike Turner and Sam Phillips, psychohistory, and whatever else–but I won’t try to summarize it here. Let’s just say it’s an eclectic mix and leave it at that.

Apocalypse Now

I didn’t see the film when it first came out, but I saw Apocalypse Now, Redux and was stunned (and a little bored). What prompted me to write about the film was a remark that Stanley Kauffman had made some years ago to the effect that, yes, there are some remarkable films, but nothing of the caliber of the finest literature. Really, I thought, really?

So when I started watching Apocalypse Now back in the summer of 2011 I wanted to see whether or not it made sense to think of a film being as good as a Shakespeare play. I convinced myself that this was a superb film and that the question of whether or not it was a good as, say, King Lear, was just silly. Shakespeare wins on poetry, lexis (?); Coppola clobbers him on gorgeousness, opsis (?), and melos as well (though I suppose this comparison is unfair in the way I’m using it as Coppola had the luxury of a sound track); on mythos, Shakespeare wins as Coppola had no plot to speak of; and it’s a wash on ethos because they’re all crazy. As for dianoia, I leave that as an exercise for the reader.

Seriously, this is a great sprawling mess of a film. There’s a section where I slowly go through the opening montage, explicating the images as they come. There’s another section where I summarize the plot, from beginning to end, just to get the whole story into my head. Early in the working paper I’d remarked how the cinematography turned the jungle itself into a character (I hadn’t read Latour at this point, otherwise I surely would have brought him in). When I’d originally posted that material it garnered me an email from Walter Murch, a Hopkins graduate who’d done the sound on the film (which got him an Academy Award), quite a bit of the editing, and who also wrote a key scene (the sampan massacre in the middle). I figured I was on to something.

But just what, in retrospect, I don’t know. I spend a great deal of time grappling with myth and ritual, not in Frye’s sense, but in the sense of Lévi-Strauss, Mary Douglas, Edmund Leach, and Arnold van Gennup, and Emile Durkheim. The film begs for such treatment, most obviously at the very end where Willard’s assassination of Kurtz is intercut with the aboriginal sacrifice of the caribao.

At one point I invoke the trope of the King’s two bodies (p. 41):

The trope of the king’s two bodies, then, is about the fiction of an artificial person, the state, that persists beyond the life of any one head of state. As such it is indifferent to the question of whether or not a king is good or bad. It’s not about the existing ruler at all, it’s about this artificial being that persists through and from one ruler to the next. It is a doctrine of continuity.But Coppola very much IS concerned about the difference between a GOOD king and a BAD one. For in his reworking of the doctrine, Kurtz is a bad king, while Willard is a good one. But the state, of course, is continuous from one to the next. That state can only be the United States of America. Both men are commissioned officers in the American Army. They are employed by the state and they come to represent it in Apocalypse Now. Kurtz is a figure for the rogue state that got into the War in Vietnam and Willard is a figure for the pragmatic state that got out.

Something like that.

Whatever else Coppola is up to in this film, he’s interrogating the state and its legitimacy. Kurtz, after all, had deserted the Army and so no longer functioned on behalf of the state. Willard was on a covert mission and in that sense didn’t exist within the state. The state would deny the existence of him and his mission.

How does the state reach outside itself to prop itself up? Is that what is being done in that animal sacrifice at the end? But those people have nothing to do with the state actors in this film, not the USA, not North Vietnam, not South Vietnam. The film ends on the image of a Bhudda’s head (taken from Heart of Darkness). The state, for all spiritual purposes, is gone.

I like what I did but I can’t say that I really have a grip on the film.

Myth and Form

Now we have two working papers, a short one, Myth: From Lévi-Strauss and Douglas to Conrad and Coppola, and a long one, Ring Composition: Some Notes on a Particular Literary Morphology, that are about form. The object of the shorter paper is to demonstrate that Heart of Darkness and Apocalypse Now have the same form, a looser kind of ring-composition that I’ve called center point construction. I do that by establishing cardinal points in each of the two texts and then arguing for a correspondence between the cardinal points in one text and the other.

The method goes back of Lévi-Strauss in Mythologies, where he establishes correspondences between different myths and then argues for “transformations” between them. I believe that last aspect of his method is, at best, confused and don’t attempt it. But establishing correspondences allows you to argue from one text to another and to see form emerge as a kind of resonance texts establish in juxtaposition.

Given that Apocalypse Now and Heart of Darkness have the same general form I then bring other texts into play in the long working paper on ring-composition. By ring composition I mean a text of the following form:

A, B, … X … B’, A’orA, B, … X, X’, … B’, A’

In the small, as you know, it’s a rhetorical figure called chiasmus. In the large, it’s not clear what it is. For the most part it’s been the tool of classicists and Biblical scholars, which is where Mary Douglas found it. She spent the last decade of her life working on the Old Testament, but also argued that Tristram Shandy was a ring–though I’ve got reservations about that argument. Once she’d alerted me to the form and got me interested, I noticed a temporal anomaly in Osamu Tezuka’s classic manga, Metropolis (1949) and, after a bit of drudge work, discovered that the text was a ring. At that point I was looking at a modern Japanese pop culture visual narrative (aka comic) sharing a form with classical and Biblical texts. The game was afoot.

It didn’t take me long to discover that two episodes of Disney’s Fantasia were rings: “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice”, which I discuss in the working paper, and “The Nutcracker Suite”, which I don’t. Over time I’ve added other texts to the group, including Gojira (the 1954 Japanese film), “To a Solitary Disciple” (Williams), a piece of literary criticism, “The Meaning of the Digital Humanities” (Alan Liu), and even “Kubla Khan,” which is where I started years ago at Hopkins.

Much of the ring composition paper is devoted to explaining why and how each of these texts meets the criteria established by Mary Douglas in her Terry Lectures, Thinking in Circles: An Essay on Ring Composition, Yale University Press (2007). As a matter of fact some of them don’t meet the criteria, so I explain why I’ve relaxed the criteria. “Kubla Khan,” for example, isn’t a narrative at all and was long regarded (and dismissed) by some as a species of word music. But its symmetries are so like those of ring-form texts that not to discuss it in this context would be foolish. And then there’s Alan Liu’s 2013 PMLA essay on the digital humanities. I certainly wasn’t looking for rings when I started thinking about his ideas, but the text reached out and said “I’m a ring!” Another accident.

What do I make of a form of textual symmetry one can find in poems, live action narrative films, animated films, a verbal narrative, visual narrative, expository writing, Western texts, Japanese texts, high culture and pop culture? What do I conclude from that? Only that there’s probably more out there, so let’s look for it. That is to say, if we look for things we’re not used to attending to, we’re going to find things, real phenomena, we didn’t know were there. Interesting things, maybe even important things. But new things.

How can we not look? Are we scholars or automata?

The issue needs to be put with a bit more subtlety, but it’s a real one. If there’s a crisis facing the discipline–institutional issues aside–it’s one of imagination, not of real intellectual possibility. The one place where there is some recognition of new opportunities is in the so-called digital humanities, with what Franco Moretti has called “distant reading” (FWIW, I think the trope of distance needs to be scrapped, but there’s no need to go into that here).

Let’s take a look.

Literary Culture and History

A couple years ago Moretti and a colleague, Matthew Jockers, established the Literary Lab at Stanford. In 2013 Jockers published Macroanalysis: Digital Methods & Literary History. He took a corpus of some 3300 19th century British, Irish, and American novels and used computational techniques to analyze stylistic and thematic features in these texts. Jockers’ corpus included canonical texts, of course, but most of them didn’t make the canonical cut. They’re texts that no one reads any longer except for scholars with very specialized interests and even then, I suspect, many of these texts are not read.

What can we learn from what Jockers’ has done? Jockers learned a lot, much of which I summarize. But most of the working paper is devoted to discovering things Jockers didn’t put in the book and that I wasn’t looking for. You see, it wasn’t merely the book I was looking through.

One of the things that Jockers did was construct what’s called a topic model for his corpus. Just what that is, is rather technical and tricky, so I’m just going to do some tap-dancing and hand-waving. The basic idea is that words that consistently occur together in a lot of different texts are probably more or less about the same general topic. It turns out that if you’ve got a lot of computer power and some sophisticated statistics you can identify which words hang together across a lot of texts. In fact, the more texts you’ve got, the better. What you want is for topics to identify themselves, in effect, against non-topic backgrounds. More texts gives you more backgrounds. So, you tell the computer how many topics you want in the model and it does a massive cross comparison to produce them.

When it’s done, it lists the words in each topic along with its frequency in the topic. It’s up to you to examine the list and determine whether or not it is in fact a coherent topic and, if so, you may choose to give it a label. Once you’ve got the themes, it’s up to you to make sense of them. You have to interpret them, to read them. Jockers discovered, for example, that English, Irish, American, and Scottish novelists had different thematic preferences, as did male and female novelists.

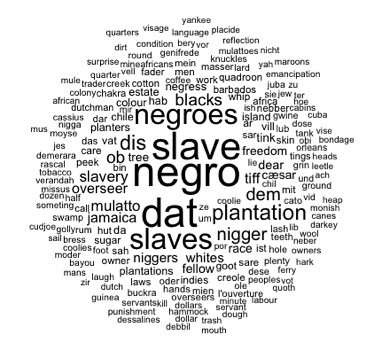

Well, when Jockers’ book came out, he also put charts of those 500 themes online so the curious reader could examine them, each and every one. Here, for example, is the word cloud for the theme that Jockers called American Slavery:

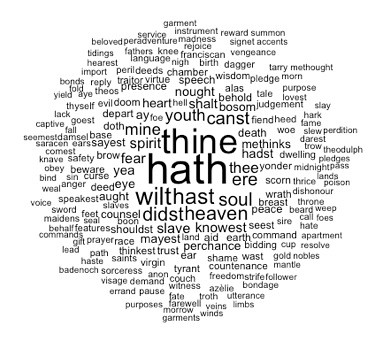

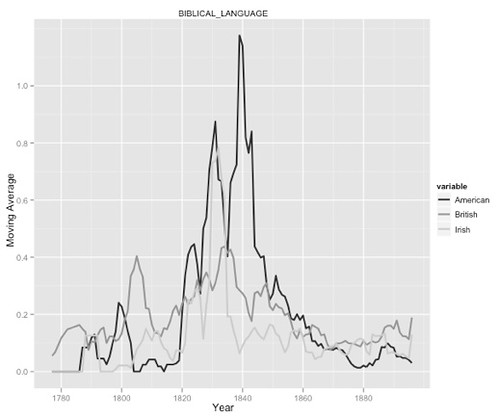

The size of the word is proportional to its importance in the topic. Here’s the word cloud for a theme Jockers labeled as Biblical Language:

Each topic also had a bar chart indicating the importance of the theme for English, British, and Irish novelists and another for Male and Female novelists. And then there were line graphs, one to show the historical distribution of the topic by gender and and one by nationality. That’s a total of 2500 “snapshots” into the evolution of themes in 3300 English-language novels in the 19th century. Those charts are available to anyone who’s got an internet connection. You don’t even need to read Jocker’s book to access them, though the book gives you important information about how he created them and contains useful examples of how to work with them. This practice is fairly typical of digital criticism.

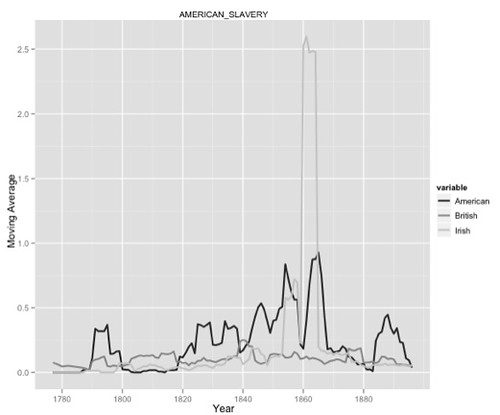

So let’s look at some of those charts. Here’s the graph showing the evolution of the slavery theme by nationality, where American is the darkest line, British is the medium, and Irish is the lightest:

The most striking thing about that is the large spike in the Irish line at the beginning of the 1860s, that is, the American Civil War. Jockers informs us that this is due mostly to the books of Mayne Reid (Macroanalysis, p. 145). The British distribution is fairly flat through the century and the American distribution, while spikey, shows a rise up to and during the Civil War.

Here’s the same graph for the Biblical Language topic:

Here the striking feature is the massive mid-century rise for the American distribution. I’d thought it might be either the second or the third awakening, but it’s between the two. Maybe it’s lagging the second or anticipating the third; maybe it’s the rise of Abolitionist sentiment; and maybe it is none of those. But the question can and must be asked. To answer it we’re going to have to look at some of those texts and look more broadly at American cultural history. And we should also look to the corpus itself; while it is a large one, it is still largely incomplete. Maybe things will be different when another several thousand texts get added.

My basic point is simple: the computer produces (interesting) artifacts which must then be interpreted in light of various kinds of knowledge, including knowledge of the texts themselves (e.g. the novels of Mayne Reid) and history (e.g. the awakenings, the Civil War). In my working paper I spend some time looking, first for the Klondike Goldrush, and then for the California Goldrush. Then I got serious and took out a critical text from the Jurassic Age, Leslie Fiedler’s Love and Death in the American Novel, and used Jockers’ data to interrogate his arguments, and vice versa. In the large, they were a reasonable fit, but I reached no firm conclusion. I was just playing around.

And then there’s the argument I mentioned up top, about the autonomy of the aesthetic realm. I take the question from one of Edward Said’s last essays, “Globalizing Literary Study,” published in 2001 in PMLA. He says:

I myself have no doubt, for instance, that an autonomous aesthetic realm exists, yet how it exists in relation to history, politics, social structures, and the like, is really difficult to specify. Questions and doubts about all these other relations have eroded the formerly perdurable national and aesthetic frameworks, limits, and boundaries almost completely. The notion neither of author, nor of work, nor of nation is as dependable as it once was, and for that matter the role of imagination, which used to be a central one, along with that of identity has undergone a Copernical transformation in the common understanding of it.

Alan Liu raised similar concerns in his 2013 PMLA essay, “The Meaning of the Digital Humanities”. Now that the author has given way to large intractable systems where is there room for us? Have we all every one of us been assimilated to the Borg?

I make two arguments that speak to this problematic. In one case I follow Jockers in resurrecting the author from the dead and in the other I reinterpret a beautiful and elegant piece of work he did on influence. But to explain those arguments I’d have to write so much about just what Jockers did and then what I did, that I would, for all practical purposes, be engaged in recreating major sections of that working paper in this letter. This is already far too long.

The terms in which Jockers is working with texts are quite different from those in which Said did his work. That means that, in order to address the question of an autonomous aesthetic realm, we’ve got to operationalize it in Jockers’ conceptual world. That requires a leap that is both epistemic and imaginative (operationalize: a concept Moretti has recently borrowed from physics). Such things are not readily explained. You just do them and see how it goes.

I like the arguments I made, I like them a lot. But I don’t know how good they are. They need to be interrogated by people who know the discourse of “big data” better than I do and by people who know Said’s discourse better than I do. In a particularly interesting world they’d also be interrogated by someone who knows both discourses better than I do. Those young people may be out there, but they’ve not yet identified themselves to me.

The Land Before Us

A couple of years ago two of those young people, Andrew Goldstone and Ted Underwood, decided to go big data on PMLA and do a topic model of the whole corpus. They published preliminary results to the web (standard practice), where I found them and entered into discussion with them, me and several others. That discussion led to this mysterious thing called philology. I mentioned having met Kemp Malone at Hopkins once. Underwood responded, “Kemp Malone (whom I had never heard of) darn near gets his own topic” (in the sense of topic I’d discussed above).

That could happen only if “Kemp Malone” appeared in many different places across many articles. And that, in turn, would require that he have been an important and much-cited scholar. Which he was.

If you’re curious you can read the whole discussion at the above link. The completed article, which covers more than just PMLA, was formally published last summer:

Andrew Goldstone and Ted Underwood. “The Quiet Transformations of Literary Studies: What Thirteen Thousand Scholars Could Tell Us”. New Literary History 45, no. 3, Summer 2014.

As is common in digital criticism, there is copious supporting material on the web.

With regards,

Bill Benzon

Computers are instruments that enhance our vision, and data processing enables us to see patterns where there were none before. What to do with those enhanced powers, that's the eternal question. One has to apply one's own powers of association and patterning to them, those that do not come along with the data, but rather with the observer. So we may get new data, which may even spark out new ideas, but that's still only half the job, the other half is as old as Heraclitus, when he said that "a wonderful harmony arises from joining together the seemingly unconnected". Or words to that effect.

ReplyDeleteof course going astray is a path

ReplyDeleteyou never did mention

a fork in the road - take it!

--

the essential point of meetance was never came

[and it was never meant to come]