|

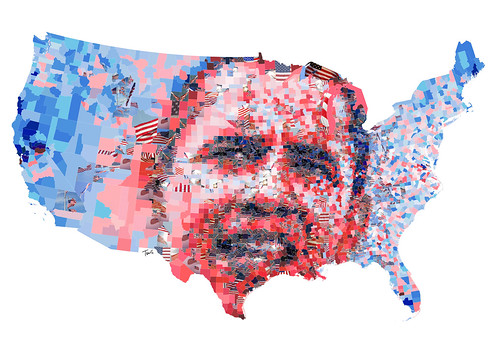

| Barack Obama: The red, the blue and the United States of America by Charis Tsevis |

* * * * *

I know what I’m doin’ and I’m fearless.

– Barack Obama, June 22, 2015

One of my regular stops on the Internet is Bloggingheads.tv, a series of online discussions produced and curated by Robert Wright, author of Nonzero, and several other books. The format is simple: two people talk about this that and the other. The people are not in the same physical location, so their conversation is mediated by appropriate web-tech.

While Wright himself is a party to many of these conversations, most of them feature others. My favorite host is Glenn Loury, an economist at Brown University, and his most frequent, though not only, interlocutor is John McWhorter, a linguistic at Columbia. On June 29, 2015, they had a conversation that started with the terrorist murders in Charlston, moved onto the Confederate flag, to Al Sharpton, and then to Obama’s Eulogy for the Rev. Clementa Pinckney. Loury initiates that discussion at roughly 38:14:

Loury’s point was that not only was Obama eloquent, as one would expect of a President (who, after all, has speech writers, though Loury didn’t say this), but that Obama delivered his eulogy in the voice and persona of a black preacher working in the vernacular tradition (and he mostly re-wrote the speech he was handed by his chief writer, though Loury didn’t say this either). His whole presentation was recognizeably African-American, which was certainly appropriate for the occasion and the audience. But when was the last time an American President ever did that?

McWhorter agreed, pointing out that we have seen “a browning of the culture […] America's all about vernacular […] He really was, in that setting, a national spokesman in a way that many other people could not be, and that he would not have been as recently as 30 years ago. We're a very different place than we used to be.” Nor could a black man have been elected to the Presidency 30 years ago, though McWhorter didn’t say that.

Obama’s Style

But then McWhorter took up the issue of Obama’s “rootedness” in this style, starting at roughly 46 minutes in:

Here’s a bit of that conversation:

JM: He wasn’t raised in this, at all. In terms of his history we know that even by the time he was in his early twenties, he was not that. He was kind of an interesting mutt. Even the black speech patterns, (as) I think about it, he didn’t grow up with those, he learned them later. And after the age when most people are good at learning new ways to talk. And the black church, he had to be told, he had to be told when he was being a black politician in Chicago that if you’re really gonna’ make you way in the black community, you have to belong to a church. […] But it’s interesting, he’s a, he’s a very, I don’t wanna’ call him fake, but he’s a very . good . performer. I don’t know if I’ve ever known any bodyGL: Ah, John...JM: who came into this sort of thing so late, and does it so convincingly.GL: […] We have to assume it’s all artifice. I don’t meanJM: In the technical sense of the termGL: Exactly. I don’t mean insincerity. I’m not going to the heart of the man. I’m saying, exactly. A mask, a face has to be made. A way of being has to be fashioned. It’s gotta be practiced.

I agree with this. But note that little hiccup over artifice. They are contending with the face that we’ve got this notion of “authenticity” which is set over against artifice, of performance against naturalness. And that just won’t do. Human behavior is too complicated for that.

Artifice comes in many forms, and they’re not all contrary to authenticity. The Presidency of the United States is itself a piece of elaborate and subtle social artifice, artifice that is independent of any all are particular occupants of the office. Modern societies are like that, composed of elaborate feats of social engineering at every scale, from the local barber shop, through the regional farmer’s association, on up to multinational corporations and elaborate national governments.

But that’s not quite the artifice that Loury and McWhorter are talking about. They’re talking about a more personal artifice, one that is enacted in performance. But performance has its subtleties.

I once saw a B. B. King concert where, late in the show, King was singing a mournful slow blues. I mean, he was getting to the point where any minute you expected the ground to become quicksand and the earth to swallow him up. He was low. And then he cocked his head a quarter turn toward the audience, flashed and ear-to-ear grin for a split second, and then allowed the earth, slowly to swallow him who.

Artifice? You bet, well practiced too. Insincere? Hmmm. When you’re in the circle of performance, where everyone can see that you’re performing, where everyone knows the game, things are different than when you’re just out and about town, or the country side. Obama may not have been raised in the black church, but that does not itself put him beyond its embrace.

And in any event, it was not Barack Hussein Obama, private individual, who delivered that eulogy. It was the President of the United States. But we’ll get to that distinction later. First let’s detour through a little cultural history.

The Annals of Performance, Black and White

![[Portrait of Duke Ellington, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., between 1946 and 1948] (LOC)](https://farm5.staticflickr.com/4093/4932369098_4133fbdc7c.jpg) |

| Portrait of Duke Ellington, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., between 1946 and 1948 by William P. Gottlieb |

Consider Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington, one of our greatest musicians. He came into his definitive style during a four-year gig at The Cotton Club at 142nd and Lenox in the Harlem section of New York City. Though the entertainment was black, the clientele was exclusively white, a common arrangement in those days. The club seated five-hundred people amid fake palms and real booze, featured shows elaborately staged, often with an exotic jungle motif.

As Ellington noted in Music is My Mistress (1973, p. 80), his autobiography:

The Cotton Club was a classy spot. Impeccable behavior was demanded in the room while the show was on. If someone was talking loud while Leitha Hill, for example, was singing, the waiter would come and touch him on the shoulder. If that didn’t do, the captain would come over and admonish him politely. Then the headwaiter would remind him that he had been cautioned. After that, if the loud talker still continued, somebody would come and throw him out.

While the clientele thus behaved impeccably, they watched light-brown show girls dance erotically, impeccably costumed in very little.

In his History of Jazz, Marshall Stearns describes a Cotton Club skit where

... a light-skinned and magnificently muscled negro burst through a papier maché jungle onto the dance floor, clad in an aviator’s helmet, goggles, and shorts. He had obviously been “forced down in darkest Africa,” and in the center of the floor he came upon a “white” goddess clad in long golden tresses and being worshipped by a circle of cringing “blacks.” Producing a bull whip from heaven knows where, the aviator rescued the blonde and they did an erotic dance. In the background, Bubber Miley, Tricky Sam Nanton, and other members of the Ellington band growled, wheezed, and snorted obscenely.

This scene typifies some important aspects of the milieu in which jazz became an active force in American culture. For one thing, it shows a segregated world straddling high-society and the demimonde in which whites control business affairs and constitute the audience. While whites didn’t constitute the entire jazz audience, they were the largest portion of the audience. The reason for this is obvious enough: the white population of America out-numbers the black population eight or nine to one.

Given these demographics it would not be difficult to interpret jazz as a neocolonial affair in which a white plantation class buys its entertainment from a subservient population of black entertainers, a reading parodied in the film, Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Indeed, many of the Cotton Club’s patrons probably had just such a view of the matter. But, however much power they, and the club’s white owners, had in the jazz world, they were not the only subjects in the room. The black musicians were reading them right back and pursuing their own agenda.

The fact of the matter is that Duke Ellington worked out many of the elements of his mature musical style in this glamorous, albeit absurd, setting. In particular he worked out the devices of what was commonly known as the “jungle” style, the obscene growling, snorting, and wheezing to which Marshall Stearns alluded. Of course this music bore little resemblance to any music originating in African jungles, or in any other African habitat and Ellington and his musicians certainly knew this. The audience probably knew it as well.

This particular jungle was a liminal space in which black musicians and white listeners would collaborate in ritual patterns across and through their cultural difference.

That was then, of course, and now is now. Ellington was an entertainer. Obama is a politician and head of state. Yet several decades after the Cotton Club gig the State Department would be happy to tour Ellington through the third world in service of America’s image.

In roughly the same mid-century time-frame a poor white boy from Mississippi would stand in the back of black churches, spell-bound by the music, and decide that the black style was for him. I’m talking, of course, about Elvis Presley. He became one of the most popular entertainers of the third quarter of the century and helped lead a rock and roll revolution. Though the music was pioneered by black musicians it was quickly taken over by white musicians, first from American and then Britain. The browning of the culture that McWhorter mentioned was in full force at this point. At the same time the Civil Rights Movement came to initial fruition in the halls of Congress.

Though this is not the time and place for a full argument on the matter – I make the argument elsewhere [1] – music was and is integral to this psycho-social process. That is to say, music is not just an epiphenomenal accompaniement to the real engines of culture and society, it is one of those engines and perhaps, over the long haul, the most powerful one of them all. And that music is rooted in the black church. Does that make the black church into one of the strongest forces in, not only African American society, but American society in general?

Still, there’s a bit more I will say here and now. This process of musically driven cultural change did not start in the early twentieth century, of course. It started much earlier. But let’s pick it up in the early 19th century as it’s beginning to pick up steam.

In The Fourth Great Awakening & the Future of Egalitarianism the economic historian Robert Fogel argued that the “spiritual capital” needed to fight the Civil War originated in camp meetings in the first quarter or so of the 19th century and was then maintained and amplified in a variety of ways (including continued camp meetings). Anecdotal evidence suggests that some, perhaps many, of those meetings were biracial and involved vigorous song of the sort we associate with fundamentalist/charismatic churches, black and white. These meetings typically took place over a period of days, even a week, and generally were rural, as was most of the country.

So, farmers and villagers would hitch up a wagon, load in their families, and travel tens of miles or more to some central location and set-up camp. They then spent a week listening to vigorous preaching, participating in vigorous song, got saved, witnessed others getting saved, and discussing religion and whatever else with their fellow Christians. This is where the abstract notions of freedom and equality came down from the rational ether to become embodied in felt imperatives for living.

If these meetings had been nothing more than polite lectures followed by polite discussion they wouldn’t have had much of an effect. In fact, if that’s what they had been, very few would have attended them, because such activities required a rather refined sensibility, more refined than most farmers, artisans, and their families had in those days.

That’s the history that Barack Hussein Obama brought trailing behind him when he delivered his eulogy to Clementa Pinckney. Let’s return to Glenn Loury.

Obama’s Choice

After he and McWhorter had hashed through Obama’s background a bit, Loury offered these remarks:

Because what does it mean for a people, I speak now of black Americans 30-40 million, to have the embodiment of their generational hopes, personified by a person who must adopt artifice, and manufacture, in order to present himself as being of them. What does it say of such a people.[…] I think this is historic profound. […] think about it, OK, the stigma of race, slavery, OK, Orlando Patterson just brilliantly analyzes this, I think. Slavery has to be, you’re putting the slave down. The slave must be a dishonored person. OK so honor, honor becomes central to the whole quest for equality.And having the Chief Executive of State, be of you, or at the very least, be a person who when in a position of choice, chose to be of you, is countering the dishonor in a very deep way. But perhaps the only way that the state’s symbolic power could be married to your quest for honor is through the President of someone who wasn’t quite fully of you. Your stigma still resonates even in the workings of history, that are intended to elevate you.

As Loury emphatically notes, on this occasion Obama was acting in his role as President of the United States. He wasn’t acting as a private individual, Barack Hussein Obama.

That private individual is obviously a gifted and talented man. He is also, as McWhorter noted, “kind of an interesting mutt” – born and raised in Hawaii by a white mother, a stint in Indonesia (long enough to pick up a bit of the language), college in Los Angeles. It’s a background that exposed him to different ways of living, and made his own identity something of a puzzle to him. He was NOT brought up in the vernacular African-American church. That is a style he had to pick up as an adult, primarily in Chicago.

That was the style that the private individual, Barack Hussein Obama, put at the service of the public role, President of the United states, in delivering a sermon on racism at the funeral for the Reverend Clementa Pinckney. When private individual and President gave voice to “Amazing Grace”, that long history of musical miscegenation, cultural appropriation, and psycho-social transubstantiation – don’t ask me what it means, but I like the feel of it – became the Word of the United States of America.

But what do those words mean? How far can we extend their implications? When Obama was talking about Dylann Storm Roof in the middle of his sermon (paragraph 21) he told us:

But he surely sensed the meaning of his violent act. It was an act that drew on a long history of bombs and arson and shots fired at churches, not random, but as a means of control, a way to terrorize and oppress. An act that he imagined would incite fear and recrimination; violence and suspicion. An act that he presumed would deepen divisions that trace back to our nation's original sin.

By “our nation's original sin” the speaker – Obama, the President? – surely meant slavery. And slavery, as we know, was the foundation of capitalism [2]. Without slavery, capitalism could not have happened. Without capitalism, no modern world.

Did the President of the United States mean to say that? Did the private man? For, as Glenn Loury has pointed out [3]

the imperatives of office in the position of the American presidency are, basically, to further the interest of the American imperial project, not to criticize that project. If one were to engage in too much of the latter, then one won’t be running the show for very long. Yet, if the history of blacks in America teaches us anything, it is that the American imperial project must be criticized.

To label slavery a sin is surely a criticism, and a deep one too. Perhaps because his sojourn in the role of President is coming to a close Barack Hussein Obama could afford to hazard that critique. And perhaps, by the conventions operative at the place and time that sermon flowed forth, the man and the role were being used by a Higher Power to get this critique indelibly inscribed in the historical record. Only time will tell whether or not Obama’s eulogy for Clementa Pinckney, this heart-felt sermon, conjoins these other fundamental documents, The Declaration of Independence and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, into a new trinity for freedom and dignity in this the Twenty-First Century.

* * * * *

From “Strivings of the Negro People” by W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, The Atlantic Magazine, August 1897:

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife,—this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He does not wish to Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa; he does not with to bleach his Negro blood in a flood of white Americanism, for he believes—foolishly, perhaps, but fervently—that Negro blood has yet a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without losing the opportunity of self-development.

* * * * *

[1] William L. Benzon. Music Making History: Africa Meets Europe in the United States of the Blues. In Nikongo Ba'Nikongo, ed., Leading Issues in Afro-American Studies. Durham, North Carolina: Carolina Academic Press, 1997, pp. 189-233. Online at: https://www.academia.edu/8668332/Music_Making_History_Africa_Meets_Europe_in_the_United_States_of_the_Blues

[2] Greg Grandin. “Capitalism and Slavery.” The Nation. May 1, 2015. URL: http://www.thenation.com/article/capitalism-and-slavery/

[3] Glenn C. Loury. Obama is No King: The Fracturing of the Black Prophetic Tradition. URL: http://www.econ.brown.edu/fac/Glenn_Loury/louryhomepage/cvandbio/Obama_No_King_new%20black%20ms.pdf

I like who you are listening in on, but y'all need to pick up on the totally disappointing 'performance' of Obama the drone-meister, killing women and kids of his complexion and darker in lands where we are not officially at war.

ReplyDeleteI'm commenting as anonymous because I hope Americans Anonymous will become an organization of peace-loving global citizens who won't get caught up in the romance of the "first colored President" quite so easily and ignore the crimes against humanity he has commited for our empire.

What can I say, this Whoa!bama is something of a mixed bag. Yes, he does have the foreign policy debacle to his (dis)credit. Maybe it's a Nixon in China thing. Do we build on this eulogy or do discount it by gigging him on his warring ways?

Delete