If you’ve heard of Dan Everett at all, most likely you’ve heard about his work among the Pirahã and his battle with Noam Chomsky and the generative grammarians. He went into the Amazon to live among the Pirahã in the mid-1970s with the intention of learning their language, translating the Bible into it, and converting them to Christianity. Things didn’t work out that way. Yes, he learned their language, and managed to translate a bit of the Bible into Pirahã. But, no, he didn’t convert them. They converted him, as it were, so he is now an atheist.

Not only did Everett learn Pirahã, but he compiled a grammar and reached the conclusion – a bit reluctantly at first – that it lacks recursion. Recursion is the property that Chomsky believes is irreducibly intrinsic to human language. And so Everett found himself in pitched battle with Chomsky, the man whose work revolutionized linguistics in the mid-1950s. If that interests you, well you can run a search on something like “Everett Chomsky recursion” (don’t type the quotes into the search box) and get more hits than you can shake a stick at.

I’ve never met Dan face-to-face, but I know him on Facebook where I’m one of 10 to 20 folks who chat with him on intellectual matters. Not so long ago I reviewed his most recent book,

Dark Matter of the Mind,

over at 3 Quarks Daily. I thus know him, after a fashion.

And so I thought I’d address an

open letter to him on my current hobbyhorse: What’s up with literary criticism?

* * * * *

Dear Dan,

I’ve been trying to make sense of literary criticism for a long time. In particular, I’ve been trying to figure out why literary critics give so little descriptive attention to the formal properties of literary texts. I don’t expect you to answer the question for me but, who knows, as an outsider to the discipline and with an interest in language and culture, perhaps you might have an idea or two.

I figured I’d start by quoting a fellow linguist, one moreover with an affection for Brazil, Haj Ross. Then I look at Shakespeare as a window into the practice of literary criticism. I introduce the emic/etic distinction in that discussion. After that we’ll take a look at Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in the course of which I introduce the question, What would I teach in a first level undergraduate class? I find that to be a very useful way of thinking about the discipline; I figure that might also appeal to you as a Dean and Acting Provost. I conclude by returning to the abstractosphere by distinguishing between naturalist and ethical criticism. Alas, it’s a long way through, so you might want to pour yourself a scotch.

Haj’s Problem: Interpretation and Poetics

Let’s start with the opening paragraphs from a letter that Haj Ross has posted to Academia.edu. Of course you know who Haj is, but I think it’s useful to note that, back in the 1960s when he was getting a degree in linguistics under Chomsky at MIT, he was also studying poetics under Roman Jakobson at Harvard, and that, over the years, he has produced a significant body of descriptive work on poetry that, for the most part, exists ‘between the cracks’ in the world of academic publication. The letter is dated November 30, 1989 and it was written when Haj was in Brazil at Departamento de Lingüística, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte [1]. He’s not sure whom he wrote it to, but thinks it was one Bill Darden. He posted it with the title “Kinds of meanings for poetic architectures” and with a one-line abstract: “How number can become the fabric on which the light of the poem can be projected”. Here’s the opening two paragraphs:

You correctly point out that I don’t have any theory of how all these structures that I find connect to what/how the poem means. You say that one should start with a discussion of meaning first.

That kind of discussion, which I have not heard much of, but already enough for me, I think, seems to be what people in literature departments are quite content to engage in for hours. What I want to know, however, is: what do we do when disputes arise as to what two people think something means? This is not a straw question - I have heard Freudians ram Freudian interpretations down poems’ throats, and I think also Marxists, etc., and somehow, just as most discussions among Western philosophers leave me between cold and impatient, so do these literary ones. So, for that matter, do purely theoretical, exampleless linguistic discussions. Armies may march on their stomachs; I march on examples. So I would much rather hear how the [p]’s in a poem are arrayed than about how the latent Oedipal etc., etc. In the former case, I know where to begin to make comments, in the latter, ich verstumme.

You’ll have to read the whole letter to find out what he meant by that one-line abstract, but I assure you that it’s both naïve and deep at one and the same time, mentioning, among other things, the “joy of babbling” and the role of the tamboura in Indian classical music. At the moment I’m interested in just those two opening paragraphs.

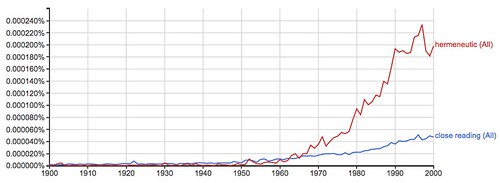

While I got my degree in literary criticism and understand the drive/will to meaning, I also understand Haj’s attraction to verifiable pattern/structures and his willingness to pursue that even though he cannot connect it to meaning. Yes, meaning is the primary objective of academic literary criticism and, yes, justifying proposed meanings is (deeply) problematic. I also know that the academic discipline of literary criticism was NOT founded on the activity of interpreting texts. It was founded in the late 19th century on philology, literary history, and editing – that is, editing the canonical literary works for study by students and scholars. Roughly speaking, the interest in interpretation dates back to the second quarter of the 20th century, but it didn’t become firmly institutionalized until the third quarter of the century. You can see that institutionalization in this Ngram search on the phrase “close reading”, which is a term of art for interpretive analysis:

Figure 1: "Close reading"

And that’s when things became interesting. As more and more critics came to focus on interpretation, the profession became acutely aware of a problem: different critics produced different interpretations, which is the correct interpretation? Some critics even began to wonder whether or not there was such a thing as the correct interpretation. We are now well within the scope of the problem that bothered Haj: How do you justify one interpretation over another?

That’s the issue that was in play when I entered Johns Hopkins as a freshman in 1965. Though I had declared an interest in psychology, once I’d been accepted I gravitated toward literature. Which means that, even as I was working as hard as I could to figure out how to interpret a literary text, I was also party to conversations about the problematic nature of interpretation. As I have written elsewhere about those years at Hopkins [2] there’s no need to recount them here. The important point is simply that literary critics were acutely aware of the problematic nature of interpretation and devoted considerable effort to resolving the problem.

In the course of that problematic thrashing about, literary critics turned to philosophy, mostly Continental (though not entirely), and linguistics, mostly structuralist linguistics. In 1975 Jonathan Culler published Structuralist Poetics, which garnered him speaking invitations all over America and made his career. For Culler, and for American academia, structuralism was mostly French: Saussure, Jakobson (not French, obviously), Greimas, Barthes, and Lévi-Strauss, among others. But Culler also wrote of literary competence, clearly modeled on Chomsky’s notion of linguistic competence, and even deep structure. At this point literary critics, not just Culler, were interested in linguistics.

Here’s a paragraph from Culler’s preface (xiv-xv):

The type of literary study which structuralism helps one to envisage would not be primarily interpretive; it would not offer a method which, when applied to literary works, produced new and hitherto unexpected meanings. Rather than a criticism which discovers or assigns meanings, it would be a poetics which strives to define the conditions of meaning. Granting new attention to the activity of reading, it would attempt to specify how we go about making sense of texts, what are the interpretive operations on which literature itself, as an institution, is based. Just as the speaker of a language has assimilated a complex grammar which enables him to read a series of sounds or letters as a sentence with a meaning, so the reader of literature has acquired, through his encounters with literary works, implicit mastery of various semiotic conventions which enable him to read series of sentences as poems or novels endowed with shape and meaning. The study of literature, as opposed to the perusal and discussion of individual works, would become an attempt to understand the conventions which make literature possible. The major purpose of this book is to show how such a poetics emerges from structuralism, to indicate what it has already achieved, and to sketch what it might become.

However much critics may have been interested in this book, that interest did not produce a flourishing poetics. Even Culler himself abandoned poetics after this book. Interpretation had become firmly established as the profession’s focus.

As for the problem of justifying one interpretation over another, deconstructive critics argued that the meaning of texts was indeterminate and so, ultimately, there is no justification. Reader response critics produced a similar result by different means. The issue was debated into the 1990s and then more or less put on the shelf without having been resolved.

I have no quarrel with that. I think the basic problem is that literary texts of whatever kind – lyric or narrative poetry, drama, prose fiction – are different in kind from the discursive texts written to explicate them. There is no well-formed way of translating meaning from a literary to a discursive text. When you further consider that different critics may have different values, the problem becomes more intractable. Interpretation cannot, in principle, be strongly determined.

What, you might ask, what about the meaning that exists in a reader’s mind prior to any attempt at interpretation? Good question. But how do we get at THAT? It simply is not available for inspection.

What happens, though, when you give up the search for meaning? Or, if not give up, you at least bracket it and subordinate it to an interest in pattern and structure as intrinsic properties of texts? Is a poetics possible? Let’s set that aside for awhile and take a detour though the profession’s treatment of The Bard, William Shakespeare, son of a glover and London actor.