01:38:27

I chose to write about Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises for this month’s column in 3 Quarks Daily: Why Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises is Not Morally Repugnant. The title is a response to an article that Inkoo Kang, a film critic, published in The Village Voice [1]:

The Wind Rises is custom-made for postwar Japan, a nation that has yet to acknowledge, let alone apologize for, the brutality of its imperial past. Nearly 70 years after Emperor Hirohito’s surrender, the Japanese military and medical institutions’ greatest evils, like the orchestration of mass rape, the use of slave labor, and experimentation on live and conscious human beings, remain absent from school textbooks.

I argued that, yes, one can read the film that way, but to do so you have to ignore some things which Miyazaki put in the film. I then point out some, but not all, of those things.

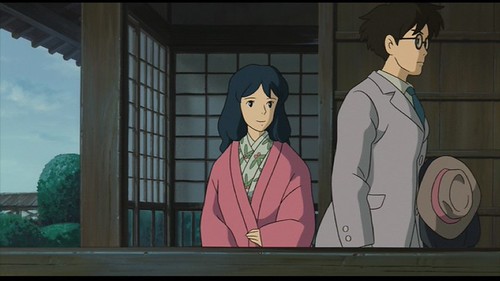

In offering her reading Kang said little about Horikoshi’s relationship with Naoko Satomi, the woman who became his wife. One thing she did say, that their marriage was sexless, is wrong, which I explained (they obviously had sex on the wedding night: 01:46:13-01:46:47). But this got me thinking, once again, about that marriage.

Cheap Melodrama

A number of critics have remarked that Satomi is not the strong assertive female lead associated with Miyazaki; she’s not like Nausicaä, Sheeta, Kiki, Fio, or Lady Eboshi, to name only the most obvious examples. She’s an artist and she’s dying of tuberculosis. While the real Horikoshi was married, his wife wasn’t tubercular and didn’t die before Japan began its war against America. Miyazaki based that aspect of his story on a short story, “The Wind Has Risen”, by Tatsuo Hori [2].

Why did Miyazaki give his protagonist such a wife? As that’s a question about Miyazaki’s intentions, we need to reframe it, as we’re not mind-readers – at any rate, I’m not. How does he use her in his story?

I’ve already pointed out how Miyazaki depicts the emergence of Horikoshi’s first successful airframe design as evolving from a dreamtime suggestion from Caproni through his initial courtship of Satomi [3]. Thus both an imagined father figure and whatever Satomi is, functionally considered (e.g. she’s not a muse), are bound to the design of that plane. What other binding does Miyazaki accomplish through her? I’m interested, not so much in what she is to Horikoshi, but, in effect, what she becomes to us.

At least one critic – alas, I forget who – noted that this aspect of the film is pure melodrama: beautiful woman, love, coughing blood, doomed marriage. Miyazaki is going for the kind of sentiment measured in tear-drenched tissues. If this were the whole film, it would be cheap melodrama. As it is, it’s cheap melodrama in service to something else.

Mount Fuji and Cherry Blossoms

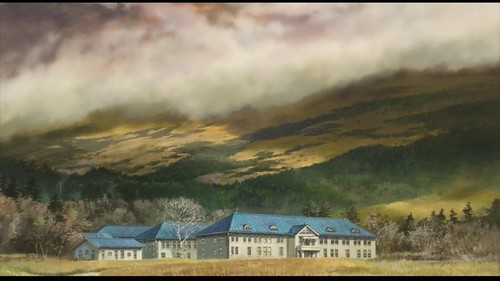

About three-quarters of the way thought the film we have a brief scene set in the sanatorium where Satomi is staying. The scene opens with the shot of Mount Fuji that I stuck at the head of this post. It then pans down to the sanatorium:

01:38:31

As Mount Fuji is all but symbolic of Japan itself, Miyazaki is thus setting up an association between Japan and the woman who will become Horikoshi’s wife a few scenes later.

Now let’s zoom ahead to the final sequence in the film. That sequence begins with a scene I described in my 3QD post. It’s late at night and Horikoshi and Honjo are walking from one building to another and talking about the vulnerability of the bomber Honjo has designed. That scene is intercut with shots of those bombers flying over China and being readily shot down by Chinese fighters. Horikoshi observes that Japan’s imperial ambitions will destroy the nation (”Japan will explode”).

As Honjo heads home, Horikoshi enters the office building and does a bit of work:

01:52:53

We cut to this, cherry blossoms:

01:52:53

And the camera pans down to a lovely morning shot where we see the room in which Satomi is sleeping (if you look carefully you can see her at the left edge of the open section of the wall):

01:53:00

Here’s a portion of the Wikipedia gloss on the symbolism cherry blossoms:

In Japan, cherry blossoms symbolize clouds due to their nature of blooming en masse, besides being an enduring metaphor for the ephemeral nature of life, an aspect of Japanese cultural tradition that is often associated with Buddhist influence, and which is embodied in the concept of mono no aware. […] The transience of the blossoms, the extreme beauty and quick death, has often been associated with mortality […] The flower is also represented on all manner of consumer goods in Japan, including kimono, stationery, and dishware.

Just as Mount Fuji is all but symbolic of Japan itself, so is the cherry blossom. The transience is, of course, apt for a dying woman.

But the cherry blossom has a more specific association, one highly pertinent to the film. Wikipedia continues:

The Sakurakai or Cherry Blossom Society was the name chosen by young officers within the Imperial Japanese Army in September 1930 for their secret society established with the goal of reorganizing the state along totalitarian militaristic lines, via a military coup d'état if necessary.During World War II, the cherry blossom was used to motivate the Japanese people, to stoke nationalism and militarism among the populace. […] Japanese pilots would paint them on the sides of their planes before embarking on a suicide mission, or even take branches of the trees with them on their missions. A cherry blossom painted on the side of the bomber symbolized the intensity and ephemerality of life; in this way, the aesthetic association was altered such that falling cherry petals came to represent the sacrifice of youth in suicide missions to honor the emperor.

Cherry blossoms are thus specifically associated with pilots and warplanes. Is Miyazaki thus binding that symbolism to this dying woman, a woman dying, not in glorious battle for the glory of Japan and the Emperor, but of tuberculosis and for no reason at all? I don’t know, but I will observe that, if you don’t know the specific associations of cherry blossoms, you can’t experience the film that way. But you can still respond to this woman’s dying. Though I’ve long known generally of the Japanese affection for cherry blossoms, I didn’t know that specific association until I began writing this post. But those nationalists that Inkoo Kang worries about, they’re likely to be quite familiar with that symbolism.

Let’s return to the film. Horikoshi enters the room:

01:53:05

His wife awakens. He lies down beside her and tells her that the design is finished. He’ll probably have to spend the next few days at the test field. As he falls asleep she extends the covers over him:

01:54:52

We cut to a scene of the oxen hauling the plane out to the test site. We’ve seen this before, along with a lament that Japan is so poor and primitive that they have to use oxen to haul the planes out.

01:54:34

We cut back to the house. Horikoshi leaves for the test site. This is the last time he’ll see his wife.

01:54:52

The test goes well. Notice the cherry blossoms along the riverbanks:

01:57:34

Moments later Horikoshi senses that his wife has died:

01:58:37

Hats are tossed in the air in elation at how well the test has gone. The pilot thanks Horikoshi for designing such a wonderful plane. The camera zooms up for a high aerial view of the plane and the jubilant men (except, of course, for Horikoshi) and then it pans right to reveal the aerial bombardment of Japan at the end of the war (how much time did Miyazaki traverse in that pan?):

01:59:23

01:59:28

The film is now over except for the final dreamtime scene in which Horikoshi will meet Caproni and then his wife.

Grieving for Japan

A question: The sadness one feels at Satomi’s death, how far does it extend along the trails of symbolic meaning – Mount Fuji, cherry blossoms, and the plane – extending through her? I don’t know. I can see what’s in the film; I can explicate connections. That’s one thing. But the question I ask is about what happens in the hearts and minds of people who see the film. It’s an empirical question, and one I don’t know how to answer.

I assume the answer will vary from person to person. I’m particularly interested in those nationalists who still cling to Japan’s imperial past. What I’m wondering is whether or not The Wind Rises might, by virtue of its web of affective associations, help them to grieve for the Japan that lost World War II. If they can grieve, maybe they can let it go. Just why I think that, well, I’m going on intuition at the moment.

My intuition on this particular matter comes from work I did on a trilogy of manga by Osamu Tezuka: Lost World, Metropolis, and Nextworld. They were published in the post war period (1948-1951) and represent an attempt to rethink Japan’s position in the world: “How did Tezuka allow the old, Imperial 'Japan' to die in his mind so that he could create a new Japan to replace it? How did he restore a sense of order and meaning to the world?” [5]. The process is both conceptual and emotional, and necessarily entails large regions of a person’s psyche.

The network of beliefs and affect that constitute one’s attachment to one’s nation are not tightly compartmentalized so that one can change them as easily as swapping out a defective processor or memory bank in a PC and replacing it with a new one. It is difficult and painstaking affective and conceptual work. It takes time. Perhaps even generations – think of those Americans who are still fighting the Civil War.

We see that process in its early stages in Tezuka’s trilogy. Six decades later it’s still ongoing in The Wind Rises. That, I argue, is how Miyazaki deploys Horikoshi’s love for a consumptive woman. As one grieves for her one grieves for … Imperial Japan, contemporary Japan, another nation (the one to which you are attached), for humankind? It all depends on who you are and what you need.

Addendum: Imperial Japan is Moribund

Finally, as I mentioned in my firstpost, Miyazaki’s mother was tubercular, and his father manufactured tail assemblies for A6M Zeroes. While the film is not autobiographical in any direct sense, it is certainly built from facets of Miyazaki’s life. Or should we say, his parents' life?

Addendum: Imperial Japan is Moribund

Written the day after I’d

written the rest of this post.

Consider the associations emanating from Naoko Satomi:

Horikoshi met her during the Great Kanto Earthquake, Japan’s greatest natural

disaster in modern times (and the single most sustained depiction of violence

in the film). Horikoshi courted her with paper airplanes, thereby associating

them with his airplane designs. He puts the final touches on his design at

night while holding her hand as she sleeps, or tries to, beside him. She’s also

associated with Mount Fuji and with cherry blossoms. For all practical purposes

she’s Lady Japan.

And she’s tubercular. She’s doomed. In one of his interviews

Miyazaki noted that at one time Tokyo was the most tubercular city in the

world [6]. Why make your Lady Japan tubercular unless, unless, you want to say that

Japan is doomed. So when, in a great romantic gesture, Horikoshi marries her

knowing that she’s doomed, well, who can fault him for that? It would be

churlish to do so. Except that this is a movie and the characters in it are

doing more than act out imaginary lives.

These characters aren’t symbolic in any crude way, nor is the story strongly allegorical. But it surely has an allegorical and symbolic dimension. And in that dimension, when Horikoshi pledges himself to Satomi, he’s pledging himself to a moribund mythos of Japan. He’s a kamikaze pilot painting cherry blossoms on the Zero he’s going to ride to his death.

These characters aren’t symbolic in any crude way, nor is the story strongly allegorical. But it surely has an allegorical and symbolic dimension. And in that dimension, when Horikoshi pledges himself to Satomi, he’s pledging himself to a moribund mythos of Japan. He’s a kamikaze pilot painting cherry blossoms on the Zero he’s going to ride to his death.

Finally, as I mentioned in my firstpost, Miyazaki’s mother was tubercular, and his father manufactured tail assemblies for A6M Zeroes. While the film is not autobiographical in any direct sense, it is certainly built from facets of Miyazaki’s life. Or should we say, his parents' life?

References

[1] Inkoo Kang. “The Trouble with The Wind Rises”. The Village Voice. December 11, 2013, URL: http://www.villagevoice.com/film/the-trouble-with-the-wind-rises-6440390

[2] Wikipedia, The Wind Rises, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Wind_Rises

[3] From Concept to First Flight: The A5M Fighter in Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, URL: http://new-savanna.blogspot.com/2015/11/from-concept-to-first-flight-a5m.html

[4] Wikipedia, Cherry blossom, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cherry_blossom

[5] Dr. Tezuka’s Ontology Laboratory and the Discovery of Japan. In Timothy Perper and Marthoa Cornog, eds. Mangatopia: Essays on Manga and Anime in the Modern World. Libraries Unlimited, 2011, pp. 37-51. Online: https://www.academia.edu/15502928/Dr._Tezuka_s_Ontology_Laboratory_and_the_Discovery_of_Japan

[6] Hiroyuki Ota, “Hayao Miyakaki: Newest Ghibli film humanizes designer of fabled Zero”, Asahi Shimbun, August 4, 2013: http://ajw.asahi.com/article/cool_japan/movies/AJ201308040009

[6] Hiroyuki Ota, “Hayao Miyakaki: Newest Ghibli film humanizes designer of fabled Zero”, Asahi Shimbun, August 4, 2013: http://ajw.asahi.com/article/cool_japan/movies/AJ201308040009

Fascinating. I had not considered Naoko as a symbol of Japan, but you're right that she is associated there with Mt. Fuji and cherry blossoms. Hmmm. I had noticed the blossoms in the shot of the plane and had noted their main cultural meaning, but I had not heard of their specific meaning for Japanese militarists and WWII pilots before now. That does put a different spin on things.

ReplyDeleteBut I'm not sure I want to go quite as far as you, here. For one thing, I think the movie is considerably more autobiographical than you give it credit for. It doesn't only parallel his parent's lives/roles/relationship, it also parallels Miyazaki's own relationship with his wife. Akemi Ota Miyazaki was an artist as well, who worked with him at Toei Animation in the '60s when he met her. But when they were married, she stayed home to raise the kids. He has written that he left the child-rearing to her because he was such a workaholic (an arrangement that put strain on his relationship with his sons), and has spoken of working late every night, then coming home and continuing to work at home late into the night. I think that scene with Jiro at his desk and Nahoko watching him is a straight out of Miyazaki's own life. In light of that, The Wind Rises may also be something of a tribute to Mrs. Miyazaki, and an admission of guilt by Miyazaki for not being there for her.

So I don't think we should look at Jiro's marriage to Naoko in a bad light. He loves her, she loves him, she is beautiful and brilliant and special, and he is right to marry her. The problem is he neglects her. He pursues his planes instead of spending time with her in her final days. If she symbolizes the old Japan that is passing, then she dies (or, rather, leaves to die) at the moment the Japanese military finally has a fighter plane that can compete with anybody in the world, giving them confidence in their imperial aggression--an aggression that will ultimately, in the space of a single cut, bring about the destruction of Japan.

Naoko isn't merely a symbol--she supports Jiro in his quest, and makes choices of her own. But then again, maybe her final decision to go away to die really only makes sense symbolically, as the passing of romanticized beauty and innocence with the coming of war. (Of course, Japan had already been attacking China for years at that point.) I dunno.

Anyway, I've checked in around here periodically to read your animation and Miyazaki posts for the past year or two, and I've found these Wind Rises writings very interesting. I haven't read your 3QD article yet, but will do so directly. I have also written about The Wind Rises, and responded to Inkoo Kang's inflammatory review on my own blog. It got pretty long, and it's not really scholarly, though I did try to source it very carefully and included extensive (and easy-linked) footnotes. But I'd be grateful if you gave it a look:

http://petrifiedfountainofthought.blogspot.com/2015/02/the-kami-electrified-world-hayao_12.html

Plus I wrote a little follow-up post that spotted images linked to previous Miyazaki projects, some of which you have already mentioned:

http://petrifiedfountainofthought.blogspot.com/2015/02/just-little-more-of-wind-rises.html

Thanks for the thoughtful comment. It took me a looonng time to see how Miyazaki had situated Naoko in the film. I'm a bit leery of saying that she symbolizes Japan, though I did use the word. "Symbol" doesn't have the right feel about it. Maybe "emblem" would be better, especially as I've used that word in connection with discussions of Apocalypse Now and "Kubla Khan".

DeleteYou're right about the personal connection between Miyazaki's neglect of his own family and Jiro's neglect of Naoko, for which is sister thrashes him. This kind of neglect is very common among men who are dedicated to their careers. And it's probably pretty common in Japan.

"Naoko isn't merely a symbol--she supports Jiro in his quest, and makes choices of her own." Of course, that's why the word "symbol" bothers me. Miyazaki is playing a very careful balancing act. " But then again, maybe her final decision to go away to die really only makes sense symbolically..." Nah, it makes sense as a human action. But the fact of her death, the fact that Jiro married her knowing that, that's also working on a different level, in a different way.

And, remember when Jiro first sees her at the resort? She's painting, and we see the painting. Then when he gets the note about her hemorrhaging, what do we see? She's coughing blood on that beautiful painting depicting the green Japanese landscape. Tricky stuff.

As for Inkoo Kang, her article's a bit confused and she mis-remembers and misreads quite a bit about the film. I'm guessing that, in addition to wanting to build a case, she only saw the film once or twice. It's really hard to remember films accurately; reviewers make factual mistakes all the time.

Yes, I'll read your post.

Fascinating! My 13-old-daughther has interpreted the film and the real story as a symbol of Japan, war and life exactly as described here.

ReplyDeleteBravo! for your daughter,

DeleteI congratulate you for the great post. I had imagined that the symbolism was in the film to show viewers that life is intense and ephemeral.

ReplyDelete