I've got another working paper available (title above):

Most of the material in this document was in an earlier working paper, Cultural Evolution:

Literary History, Popular Music, Cultural Beings, Temporality, and the Mesh, which also has a great deal of material that isn’t in this paper. I’ve created this version so that I can focus on the issue of directionality and so I’ve dropped all the material that didn’t related to that issue. The last section, The Universe and Time, is new, as is this introduction.

* * * * *

Abstract: Matthew Jockers has analyzed a corpus of 19th century American and British novels (Macroanalysis 2013). Using standard techniques from natural language processing (NLP) Jockers created a 600-dimensional design space for a corpus of 3300 novels. There is no temporal information in that space, but when the novels are grouped according to close similarity that grouping generates a diagonal through the space that, upon inspection, is aligned with the direction of time. That implies that the process that created those novels is a directional one. Certain (kinds of) novels are necessarily earlier than others because that is how the causal mechanism (whatever they are) work. This result has implications for our understanding of cultural evolution in general and of the relationship between cultural evolution and biological evolution.

1. Introduction: Direction in Design Space, Telos? 2

2. The Direction of Cultural Evolution: The Child is Father or the Man 6

3. Nineteenth Century English-Language Novels 9

4. Macroanalysis: Styles 10

5. Macroanalysis: Themes 13

6. Influence and Large Scale Direction 15

7. The 19th Century Anglophone Novel 18

8. Why Did Jockers Get That Result? 20

9. What Remains to be Done? 21

10. Literary History, Temporal Orders, and Many Worlds 22

11. The Universe and Time 30

Introduction: Evolving Along a Direction in Design Space

In 2013 Matthew Jockers published

Macroanalysis: Digital Methods & Literary History (2013). I devoted

considerable blogging effort to it 2014, including most, but not all, of the material in this working paper. In Jockers’ final study he operationalized the idea of influence by calculating the similarity between each pair of texts in his corpus of roughly 3300 19th century English-language novels. The rationale is obvious enough: If novelist K was influenced by novelist F, then you would expect her novels to resemble those of F more than those of C, who K had never even read.

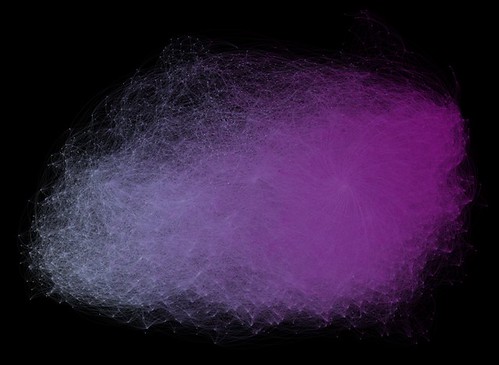

Jockers examined this data by creating a directed graph in which each text was represented by a node and each text (node) was connected only to those texts to which it had a high degree of resemblance. This is the resulting graph:

It is, alas, almost impossible to read this graph as represented here. But Jockers, of course, had interactive access to it and to all the data and calculations behind it. What is particularly interesting, though, is that the graph lays out the novels more or less in chronological order, from left to right (notice the coloring of the graph), though there was no temporal information in the underlying data. Much of the material in the rest of this working paper deals with that most interesting result (in particular, sections 2, 6, 7, 8, and 10).

What I want to do here is, first of all, reframe my treatment of Jockers’ analysis in terms of something we might call a design space (a phrase I take from Dan Dennett, though I believe it is a common one in certain intellectual circles). Then I emphasize the broader metaphysical implications of Jockers’ analysis.