This is and edited version of an interaction I had with Claude 3.5 Sonata in which I asked it to present a conversation between Archimedes, Goethe, and Musk. These three could never have had such a conversation, of course, because they lived at different times, not to mention in different places. I got the idea from Steve Allen, who had a television show based on that concept. He called the show, Meeting of Minds.

I started the conversation with a prompt. Claude’s initial response was to imagine the possibilities. When they were done imagining, I told them to get on with it. Every so often I’d intervene with a comment. I’ve removed those. At one point Claude had Archimedes talking about gravity. When I pointed that out, Claude laughed (that is, responded with “laughing heartily”), noted that he wouldn’t have known about gravity, and revised the offending response. I edited that out as well. Here’s the final result.

* * * * *

Steve Allen, the American entertainer, had a program called “Meeting of Minds,” in which he imagined that historical figures, who had not in fact met, would meet for conversation. I wonder how things would go in a conversation between Archimedes, Elon Musk, and Goethe. Do you have any thoughts or ideas?

What an intriguing thought experiment! This meeting would be fascinating given their diverse perspectives and shared innovative spirits. Let me imagine their conversation:

Archimedes would likely be immediately curious about modern technology, particularly Musk’s rockets and electric vehicles. I can imagine him saying something like “So you’ve managed to escape Earth’s pull entirely? Show me the calculations!” He might quickly sketch geometric proofs in the sand (or on a napkin) to understand the orbital mechanics.

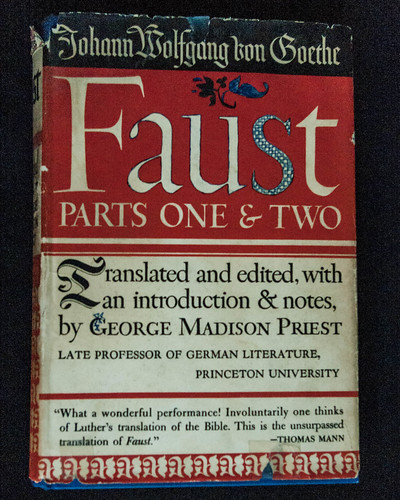

Goethe, wearing multiple hats as both scientist and poet, might challenge Musk on the philosophical implications of his Neuralink project: “You seek to merge man and machine, but what becomes of the human spirit? Of the eternal Streben - the striving - that defines us?” He might see it as a modern Faustian bargain.

Musk might respond by explaining how technology could enhance rather than diminish human potential, while Archimedes nods approvingly at the technical details. But then Archimedes might interject with concerns about the practical safety measures, recalling his own work designing defensive weapons for Syracuse.

I can imagine Goethe bringing up his color theory and his holistic view of nature, leading to a heated debate with both Musk and Archimedes about the scientific method. Archimedes might side more with modern empiricism, while still appreciating Goethe’s broader philosophical concerns.

One particularly interesting moment might come when discussing Mars colonization. Archimedes might see it as a brilliant application of his principles of mechanics and mathematics, while Goethe might view it through the lens of his concept of human striving toward the infinite. Both might be fascinated by, but perhaps also wary of, Musk’s ambitious timeline and goals.

Would you like me to explore any particular aspect of this imagined conversation in more detail? I find the intersection of their views on technology and human progress especially intriguing.

Could you imagine a bit of their conversation, perhaps starting with introductions. I’d imagine that, as the one most experienced in diplomacy, Goethe would take the lead.

Goethe: adjusting his cravat with characteristic poise “Gentlemen, what an extraordinary gathering! I am Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, privy councilor to the Duke of Weimar, though perhaps better known for my literary works and scientific inquiries. turning to Archimedes with genuine curiosity I have long admired your mathematical insights, particularly your work on the lever.”

Archimedes: glancing up from a napkin already covered in calculations “Χαίρετε! Though I see we’re speaking across languages somehow. I am Archimedes of Syracuse. pointing to his sketches I was just considering how your modern flying machines might relate to my work on floating bodies. Most fascinating.”

Musk: checking his phone briefly before pocketing it “Elon Musk. I run SpaceX, Tesla... pausing Actually, Archimedes, you’d probably be interested in our Starship project. We’re basically building the largest lever ever made - a rocket that can lift 100 tons into orbit.”

Archimedes: eyes lighting up “Give me a place to stand, and I shall move the world! But you’ve found a way to move beyond it entirely? reaching for another napkin Show me your fuel calculations.”

Goethe: leaning forward with interest “Herr Musk, before you lose our Syracuse friend entirely to rocket equations, perhaps you could explain something that’s been puzzling me. In my ‘Faust,’ I explored humanity’s endless striving for knowledge and progress. Your ventures seem to embody this spirit, but at what cost to the human soul?”

Musk: shifting in his chair “The human soul? Look, we’re at a crucial point in civilization. We need to become multiplanetary before some catastrophe wipes us out. And AI is advancing faster than most people realize. These aren’t just engineering problems.”