Once more I'm bumping this to the top of the queue, this time in remembrance of Dick Macksey, who has just died, three days shy of his 88th birthday. In 1999 he sat down with Mame Warren and talked about the history of Johns Hopkins. The material is online, voice recordings and a transcript.

* * * * *

[From Sept. 2018]

Over the last two weeks or so I've read more than I can stand about the sad case of Avital Ronell, Nimrod Reitman, and NYU. It doesn't have to be like that, and at many places it isn't. I'm reposting this from five years ago. Note my account of graduate school at SUNY Buffalo. These accounts are of times past, over three decades ago. Adjunctification hadn't set in yet.

* * * * *

[From Oct. 2013]

The Three: The Johns Hopkins University, the English Department at SUNY Buffalo back in the 70s (hottest department in the country), and Renssalaer Polytechnic Institute.

I grew up in western Pennsylvania in a suburb of Johnstown, a small steel-making city. My father was from Baltimore and he worked with Bethlehem Mines, the mining subsidiary of the now-defunct Bethlehem Steel Corporation. My mother was a native of Johnstown, had been there for the 1937 flood, and was a full-time housewife and mother. That was typical for the time, the 1950s and into the 60s.

Mother loved gardening and she was an excellent cook and seamstress. Father was more intellectual than most engineers. In addition to playing golf, collecting stamps, and woodworking, he liked to read, both fiction and nonfiction. Both parents played the piano a bit and enjoyed playing contract bridge.

I spent many hours happily immersed in books from my father’s library (which contained many books from his father’s library): Arthur Conan Doyle, Rafael Sabatini, Rider Haggard, Charles Dickens, and Mark Twain among them. I went to school in Richland Township. The schools were above average, but not special. They did not regularly send students to elite schools.

I’d applied to three Ivies, Harvard and Yale, which turned me down, and Princeton, which wait-listed me. I’d also applied to The Johns Hopkins University, my father’s alma mater. They accepted me. That my father had gone there no doubt weighed in the decision.

A classmate of mine, quarterback of the football team, was accepted to Princeton. I believe he was the first student from the school to go to an Ivy League school. I don’t think he was very happy there.

I can’t say that I was happy at Hopkins either. But then I didn’t go there for happiness. I went there to get an education, which I did.

The Johns Hopkins University

Hopkins is probably the most distinguished of the elite schools I’ve been associated with. I did my undergraduate work there between 1965 and ’69 and then completed a Master’s degree in Humanities between 1969 and ’72 while at the same time working in the Chaplain’s Office as an assistant. This was at the tail end of the Vietnam War era and I was a Conscientious Objector to military service. I thus had to perform civilian service instead of being drafted into the military. That’s why I worked in the Chaplain’s Office.

After a so-so high school outside a small city in western Pennsylvania the intellectual life at Hopkins came as a welcome revelation to me. Ideas seemed important. Well, sorta’.

At the same time it was clear that coursework had its limitations. If a course clicked, then I tended to lose interest in assigned coursework for the last half or third of the semester. Instead, I’d immerse myself in whatever had attracted my interest. If a course didn’t click, well, I managed to stick it out.

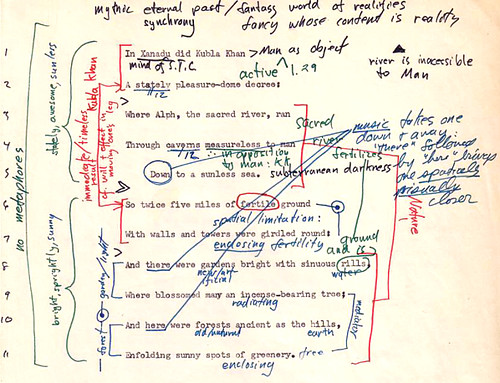

What made Hopkins work was finding Dr. Richard A. Macksey, a polymath who taught comparative literature (in English translation for those who couldn’t read French, German, Italian, or Russian) through the interdisciplinary Humanities Center. I took several courses with him, an independent study, and subsequently did my Master’s under him. Other individual faculty were important as well, particularly Mary Ainsworth, Arthur Stinchcombe, Neville Dyson-Hudson, and Earl Wasserman.

But Macksey was the guy. Without him I’d have had a more difficult time graduating from Hopkins. He provided relief from the “system” and he knew that. Other students were attracted to him and studied with him for the same reason. He was particularly important to students interested in film since he taught a film workshop thereby enabling them to get academic credit for their passion. At least two students slightly older than me went on to distinguished careers in Hollywood (Caleb Deschenel and Walter Murch) and there may well have been others as well.

In terms of sheer brilliance I’ve never worked with anyone superior to Macksey and very few his equal. For whatever reason, he chose to work with and develop others rather than develop a large body of his own research. He taught many courses, more than required of him, and always had a group of students whom he worked with independently.

It would be interesting to compare his record as a talent scout with the record of the MacArthur Fellows Program. There would, of course, be a calibration problem. Macksey went at it for six decades or so (he only retired a couple of years ago) whereas the MFP has only been around for just over three decades. On the other hand the MFP has had more resources at its disposal.

Macksey is most-widely known, however, as the long-term editor of the comparative literature issue of MLN (Modern Language Notes) and as one of the organizers of the in/famous structuralism symposium of 1966: The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man. While Jacques Derrida is perhaps the best-known figure that spoke at the symposium, he was a relative unknown at the time. In fact, he wasn’t even supposed to be there. He was invited as a last-minute replacement for Luc de Heusch. The paper Derrida delivered, “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,” undercut structuralism as a movement and made him a star.

Though I was on campus at the time I didn’t attend the symposium – it wouldn’t have done me any good as it was delivered in French. But Macksey distributed an English translation of Derrida’s paper in one of his classes and I devoured it. It became one of my central texts for a while, though it didn’t diminish my enthusiasm for Lévi-Strauss.

At the time, of course, no one foresaw the consequences of the intellectual currents that organized themselves through that conference. For one thing, the conference was organized as a new beginning, a beginning in the New World, for structuralism as an interdisciplinary mode of investigation. Instead, it functioned as the beginning of the end.

* * * * *

And then there is Chester Wickwire. When I entered Hopkins he was the Executive Secretary of the Levering Hall YMCA. The YMCA subsequently decided to withdraw from the campus, at which time the University took over the building and Wickwire became University Chaplain.

Wickwire was an activist. He was central to both the civil rights and anti-war movements in Baltimore. In the spring of 1966 he brought Bayard Rustin to campus, which inspired the Ku Klux Klan to burn a cross next to Levering Hall. He also ran a tutorial program in which inner city (aka ghetto) kids were brought to campus on Saturday mornings where Hopkins undergraduates helped them with schoolwork. These activities made him suspect among the more conservative folks at Hopkins.

I volunteered at the coffee shop Wickwire ran in Levering Hall, The Room at the Top, and in two film series he ran, one for classic American films and the other for foreign films. Dick Macksey advised Wickwire on films for both series and often held late-night discussions of the films at his house after the evening showing.

One summer Wickwire decided to book some films into the main campus auditorium, Shriver Hall, to raise some money. Chet was forever raising money, because, well, his programs needed it. We picked films that we thought would fill a 1000+ seat auditorium for two shows.

One of those films was John Waters’ Pink Flamingos. This was in the early 1970s before Waters had developed much of a national reputation, but he was well-known in the Baltimore area. As Pink Flamingos had never before been shown in Maryland it had to go before the Maryland Board of Censors for approval – the only such state-level board in the nation. One scene in particular was in notorious bad taste, even by Waters’s standards: a small dog defecates in front of Divine, the film’s transvestite star, and she scoops the feces up so as to deliver a ****-eating grin.

In order to provide a bit of intellectual cover for this cheapest of cheap tricks, we – I forget just who – decided that Macksey should sign a brief but edifying essay about the film. Without ever having seen the film, I drafted the essay, Macksey OKed it, and we included it in the package that went before the censors. They approved the showing and the film played to a packed house. Chet made his money and we all had some fun.

* * * * *

Finally, I should mention Lincoln Gordon. A former United States Ambassador to Brazil, he succeeded Milton Eisenhower (Ike’s brother) as university president in 1967. He introduced coeducation to the undergraduate program in 1970 and was forced out of office by the faculty in 1971. The Wikipedia says that financial problems forced him to cut budgets and that displeased the faculty. No doubt. What I remember is that for some reason the faculty thought him arrogant. Whatever.

The point is simply that faculty displeasure did force him to resign. Universities are like that, at least some of them.

Faculties are by and large intellectually conservative. Academic research and scholarship are not “boldly go where no man has gone before” kinds of business. Library stacks are finite in length and someone has always been over every inch of them at one time or another. Thus I’m pretty sure that intellectual life at Johns Hopkins is still dominated by the walls between departments that Macksey found so troublesome.

At the same time faculty members tend to be prickly and independent minded. The faculty at Hopkins forced Lincoln Gordon out; years later the faculty at Harvard would force Lawrence Summers out.

There is a certain looseness about such institutions that allows interesting people to survive here and there in little nooks and crannies. Some of them may well be geniuses, but that’s not by institutional design. It’s merely accidental.

The English Department at SUNY Buffalo

Not so long before I’d arrived there in the fall of 1973 the State University of New York at Buffalo had been a private university, the University of Buffalo, and it was still known by those initials, “UB”. The State University of New York (SUNY) system had acquired it with the intention of transforming it into a Berkeley of the East. Student riots in the early 1970s, however, scared the local gentry and they put the breaks on any massive upgrading.

But not before the Department of English had been turned into the finest experimental program in the nation and not before David Hays was able to establish an eclectic Department of Linguistics. I did most of my coursework in English, as that was the department in which I was enrolled. However, as I’ve explained elsewhere (e.g. in this essay on computational linguistics and literary study), I got my real education with David Hays. The English Department was fully aware of that and had no problems with it.

For at least a decade, the UB English department was the most interesting English department in the country. Other universities had the best English departments for history or criticism or philology or whatever. But UB was the only place where it all went on at once: hot-center and cutting-edge scholarship and creative writing, literary and film criticism, poem and play and novel writing, deep history and magazine journalism. There was a constant flow of fabulous visitors, some here for a day or week, some for a semester or year. The department was like a small college: 75 full-time faculty teaching literature and philosophy and film and art and folklore, writing about stuff and making stuff. Looking back on it from the end of the century, knowing what I now know about other English departments in other universities in those years, I can say there was not a better place to be.

I have no reason to contradict that judgment.