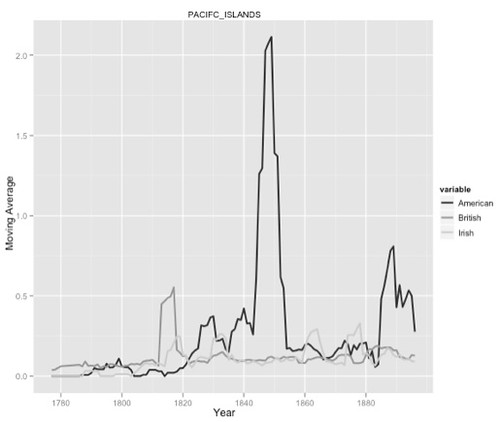

This post is from Aug. 31, 2014, but I'm bumping it to the top of the queue as I am thinking about these matters in connection with Moretti and Sobchuk, Hidden in Plain Sight: Data Visualization in the Humanities (New Left Review 118, 2019, 86-119). They don't discuss this visualization, but they should have.In this post I suggest some studies I’d like to be done. I begin by recalling Moretti’s account of genre succession from Maps, Graphs, Trees in the context of Jockers’ massive graph of literary influence. Then I revisit the “Style” chapter and look at some of the work I passed over when I first posted on that chapter, the work related to Moretti’s generational observation. I then make some suggestions about how we could infer quasi-genres in the data assembled to build the influence graph and thereby extend Jockers’ work on style from his limited corpus of 106 texts to the larger corpus of 3346 texts. I conclude with some vague and tentative remarks about the pattern of reader interest betrayed in the record we’ve been examining, that of book publication.

Influence and Genre Succession

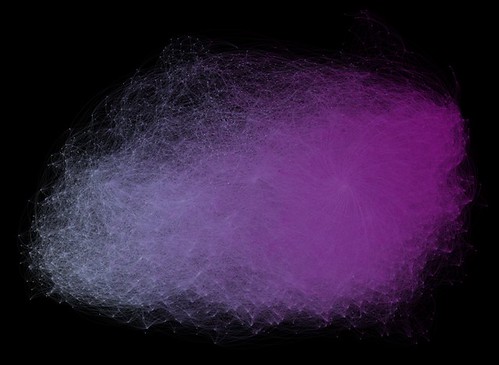

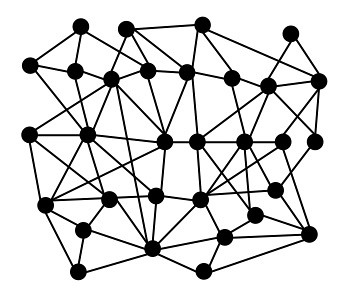

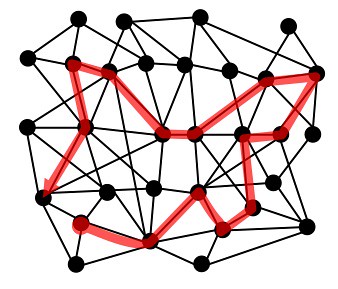

I’ve been thinking a lot about two things: 1) Moretti’s argument in Graphs, Maps, Trees that genres tend to cluster into 30 year cycles, and 2) Jockers’ massive graph in which all 3346 texts in his corpus are linked by relations of similarity, producing a graph that looks like this (which is Figure 9.3, p. 165; color version from the web):

As Jockers points out, what’s remarkable about this graph is that the nodes are ordered in time from left (oldest) to right, but there is no temporal information in the data from which it was derived: “Books are being pulled together (and pushed apart) based on the similarity of their computed stylistic and thematic distances from each other” (p. 164).

That temporal ordering is a side effect of ordering by thematic and stylistic similarity. But, in the abstract, it could have been otherwise, no? Why should positioning texts near similar texts result in temporal ordering? (Would the same thing be true of 20th Century texts?) This ordering implies that the evolution of literary culture IS directional, but Jockers himself hasn’t posited any telos, nor do I see any need to do so. That directionality stems from the internal dynamics of the system. Authors, and I assume audiences as well, want to stick with what they know, and what they know was published in the previous years.

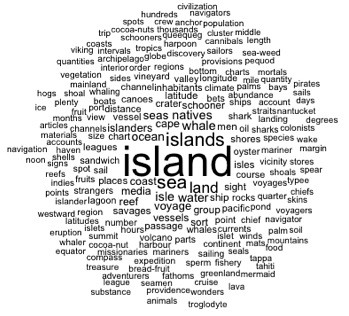

It seemed to me that Moretti’s cycles must somehow be in that graph, for all the texts in a given cycle are close together in time, by definition, as well as similarity. Alas, the whole corpus has not been coded for genre (p. 158). Is there some way we can back into genre since we’ve got this massive graph based on similarity relations among texts along 578 dimensions? Aren’t texts within the same genre more likely to resemble one another than texts in different genres?

The other thing on my mind is the fact that what really interests me is what’s on people’s minds and how that evolves over time. Some books will attract few readers, some books many readers; but the mere fact that a book has been published doesn’t speak to that. Moreover, books can be read long after they’ve been published. In the case of Moby Dick, it would seem that, for the most part it was read only long after it was published. Publication history is, at best, an indirect proxy measure of that.

And yet that history IS a history. Assuming that publishers are for the most part rational economic actors who want to turn a profit, their decisions on what to publish must take into account their sense of what people are reading and therefore what they’re buying. And the kinds of books that got published changed from one decade to the next. That record of changes must reflect changes of reading taste.