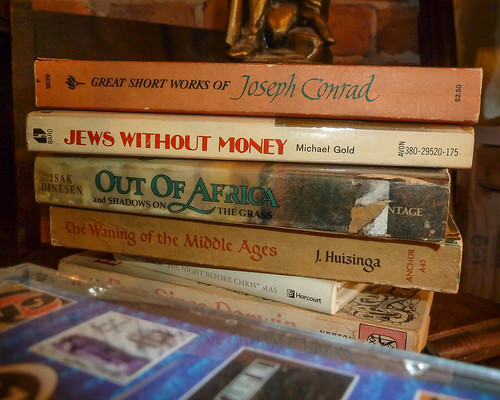

A couple of weeks ago I posted “

In search of a small world net: Computing an emblem in Heart of Darkness” [1], which was about a computational procedure for establishing that a phrase we can call the Emblem is ‘central’ to Conrad’s text. Here is the phrase, in one of two slightly different versions:

My Intended, my ivory, my station, my river, my—. A colleague asked me, in the person of more traditional critic:

If this were true, why would we need computation to prove it? That is, since I’ve already made an argument in more or less traditional terms, what’s the point of the computational exercise?

To a critic for whom such questions are real, I have no response.

But I am not such a critic.

To be sure, my degree is in English literature, from the State University of New York at Buffalo in ancient days of 1978. But my dissertation was, in a large degree, an exercise in knowledge representation of the sort then current in the cognitive sciences. By the time I had completed my degree I ‘spoke’ both literary criticism and cognitive science with native competence. As a literary critic I can read Heart of Darkness, spot Kurtz’s Emblem, note its ‘centrality’, and make a fairly standard kind of case for it. But for my cognitive science side, what does that mean, ‘central’ to the text? The standard critical argument doesn’t satisfy my curiosity. Thus I’ve suggested the small-world-net exercise to satisfy the cognitive scientist in me.

But that’s not a reason for a literary critic to pay attention to that kind of argument. From my point of view, such a critic suffers from a limited imagination, an imagination confined to the prison-house of discursive criticism [2].

The standard argumentation I’ve offered about the centrality of the Emblem ultimately rest on intuitions about texts and language. What does it mean to talk of the semantic center of Heart of Darkness, or any other text for that matter? What do we mean by center, anyhow? Certainly not the physical center of the book itself. We mean the center of, well, you know, the ‘meaning space’ of the text. And what is that?

The fact is for years critics have been using loose spatial imagery in talking about texts. Texts have insides and outsides, so that some things are in a text while others are not. The text is capable of hiding meaning. It also has a surface, and that surface can be read. Such a so-called surface reading is of course different from a close reading, which is certainly different from distant reading. Do texts also have semantic edges as well? What about a top and a bottom?

We’re so used to this imagery that we don’t notice that it’s pretty much built on nothing. These vague spatial terms constitute our rock-bottom understanding of texts, not as physical objects, but as mental objects. We’ve agreed on these terms and have arrived at ways of using them but, really, what are we saying? There’s very little there.

It may see strange to think of such language as the bars and walls of a conceptual prison, but that’s what it is. It limits how we allow ourselves to think about our craft. We defend this language, not because it’s perspicuous, but because it’s comfortable – and we’ve grown lazy and complacent.

I've you've of a mind, better pour yourself a drink. This is going take awhile.

Beyond the transcendental homunculus: What’s next for literary criticism?

What kind of a future does this standard spatialized literary criticism have? Forget about current institutional pressures for the moment. In purely intellectual terms, what’s the future of literary criticism? Where is there to go?

For years I’ve been reading that there’s been no substantial new development since Barbara Butler and queer theory. I’m not entirely sure that’s true. Does animal studies count? What about eco criticism? Is Tim Morton a major figure? He’s given the Wellek Lectures (2014); he’s touring the world giving speeches these days; Bjork has endorsed his work and I believe he’s completing a general audience book for Penguin. Sounds pretty major to me. And I think he’s brilliant. But – the future of literary criticism?

What tools does discursive criticism have for thinking about the mind? I submit that the most important tools are the texts themselves – a theme to which I’ll return – along with the critics’ ability to spot interesting patterns in the texts. But when it comes to explaining those patterns, what tools?

As far as I can tell, those tools various kinds of mental faculties operated by invisible homunculi. That’s what psychoanalytic psychology (in its various forms) is like–and, by the way, I actually like psychoanalytic ideas and use them in my work [3]. As far as I can tell that’s the most explicit ‘model’ on offer. Ideology? What’s that but a hegemonic mental faculty operated by an authoritarian homunculus, and a transcendental homunculus at that, though we try hard to pretend that these guys (they’re always guys) are immanent. I’m exaggerating of course, but in comparison with the work that’s been done in the cognitive a neurosciences over the past half-century, the psychologies of literary criticism are pretty ghostly.

No, I believe that what we (in my person as a literary critic) have to offer is the texts themselves, and the patterns we spot and describe in them. Consider these remarks by Tony Jackson [4, p. 202]:

That is, a literary interpretation, if we are allowed to distinguish it as a distinct kind of interpretation, joins in with the literariness of the text. Literary interpretation is a peculiar and, I would say, unique conjunction of argument and literature, analytic approach and art form being analyzed.

That’s obvious enough, isn’t it? An interpretation is coupled to the text, and draws its substance from the text. Certainly it draws its claim to authority from the canonical text, not from the critic, who is merely an academic.

Taken by alone, the conceptual apparatus we use in interpretation is thin. Perhaps that’s one of the problems of critique, the ratio of interpreting theory to object text has tipped too far toward theory, resulting in an intellectually thin and unsatisfying discourse. Is it any coincidence that this era of High Theory has also given rise to the star critic who is granted the authority of that same Theory?

Can academic literary criticism thrive and prosper under a regime where theory works hard to pry itself free of literary texts, rendering them mere examples for displays of critical brilliance?