Psychoanalysis has been the psychological discipline that has had the most influence on literary criticism, along with Jungian depth psychology and perhaps Gestalt psychology as well. In the middle 1950s and into the 1960s computation hit the behavioral sciences and a movement that came to be called cognitive science emerged. The neurosciences came of age and 1970s sociobiology gave way to 1980s evolutionary psychology. This post is about these newer psychologies.

But I don’t intend an in-depth discussion or even a brief survey of how these psychologies are being used in literary criticism. My purpose is more abstract and schematic.

Psychology: The Five-Fold Way

In 1978 I filed a dissertation on “Cognitive Science and Literary Theory” [1]. Since cognitive science was a rather new development at that time – the term itself was coined by Christopher Longuet-Higgins in 1973 – I devoted a chapter to explaining what cognitive science was. My account was necessarily idiosyncratic. Cognitive science has never been more than a loosely associated agglomeration of themes and interests ultimately impelled by the idea of computation. For the arguments in my dissertation I needed a bit more than was then (and even now) implied by “cognitive science” argued that it was about investigating a five-way correspondence between: 1) computation, 2) behavior, 3) the brain and nervous system, 4) ontogeny, and 5) phylogeny. And the dissertation itself discussed each of those.

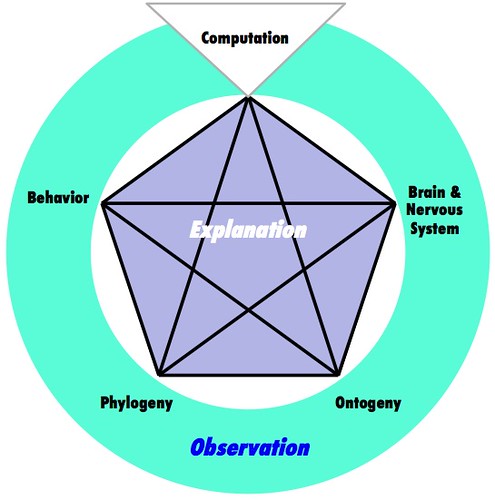

Consider this informal diagram:

I’ve arranged each of those five concerns at the corners of a pentagram. Except for computation, they are fields of phenomena to be observed and explained. Computation is introduced as a set of devices for crafting explanations of observed phenomena.

Psychology is most centrally concerned with explaining human behavior. What kinds of computational mechanisms would explain this or that observed human behavior? Moving counter-clockwise around the circle, one can ask the same question for the behavior of any animal and so develop a computational approach to comparative psychology and to the evolution of behavior. Similarly, one can develop a computational approach to the behavior of a creature at any phase of its life cycle, ontology. Computational approaches to language acquisition have been under study for decades. And computational neuroscience – brain & nervous system – is richly developed.

Just how these research possibilities are apportioned into organized disciplines – departments, professional societies, journals, conventions, and so forth – that’s a secondary matter. As a practical matter while cognitive science has its journals and conventions, there are few departments of cognitive science. It exists in universities mostly as interdepartmental programs.

The Five-Fold Way in Literary Study

While cognitive science has its origins in the encounter of behavioral science with computation, cognitive poetics and cognitive rhetoric have shown little interest in computational models – a point I’ve made at length in two working papers [2]. The cognitive study of literature is thus stunted in its development and concentrates mostly on literary behavior – texts in the mind – and has shown some interest in the nervous system.

Literary Darwinism has no interest computation either, but, like cognitivism, has a notional interest in the brain [3]. Rather it concentrates on the relationship between behavior and phylogeny, and a rather restricted portion of phylogeny at that. It’s greatest interest is in the evolution of humankind from apes, and for good reason, of course.

Both cognitive criticism and evolutionary criticism supplement their psychology with concepts from fairly standard literary criticism, though with different emphasis. In particular, neither has shown much interest in cultural evolution as a mode of investigating literary history nor has either betrayed much interest in literary form.

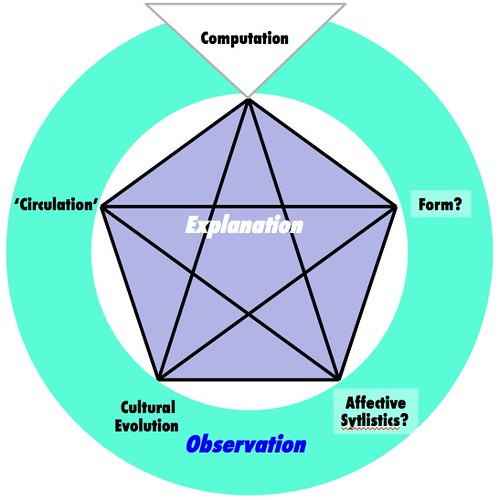

Consider this diagram, which I derived from the first one by relabeling the corners of the pentagram:

Keep in mind that this diagram, like for former, is informal. And the relabeling is tentative, along with some of the conceptions that go with it. The point is simply that we have to refit the entire disciplinary pentagram for a fully contemporary approach to literature. That first diagram is about human psychology. This diagram, if you will, is about the life of literary texts, which I consider to be a kind of cultural being.

These cultural beings evolve. Thus instead of phylogeny I have cultural evolution at the lower left. That I’m sure of [4]. That evolution happens on a time scale of decades, centuries, and millennia.

Next to it, as a relabeling of ontogeny, I’ve adopted a phrase from the early theoretical work of Stanley Fish, affective stylistics. By that Fish mean the evolution of the reader’s experience in the course of reading a text. Why would that parallel ontogeny? In biology, ontogeny is the development of a mature organism from germ cells. It is something that happens in time. So does the experience of a literary text. Think of the physical text itself as consisting of gene-like elements (I’ve come to call them coordinators [5]) which the reader develops into a rich experience through some period of time. This happens on a much shorter time scale: seconds, minutes, and hours.

Continuing clockwise, “form” is literary form, something we observe and thus attempt to explain. We observe literary form by describing it, just as naturalists describe the forms and lifeways living creatures [6]. One long-term objective of literary studies is to characterize the computational processes the underlie the literary forms that we observe. It is the time-course of those calculations in seconds, minutes, and hours that give rise to affective stylistics. Similarly, as literary forms evolve over time, so do the computational processes underlying them. The computational processes involved in reading a novel are not the same as those involved is listening to an epic poem, or reading the text of one [7].

The leaves us with “circulation”, which I’ve used to relabel the behavior corner. In the first diagram I mean human behavior. In this diagram, then, we’re interested in the behavior of literary texts. How do they behave in society? That is, how do they circulate – I’ve taken the word from Stephen Greenblatt. On this point I would cite a book by an economist, Arthur De Vany, Hollywood Economics: How Extreme Uncertainty Shapes the Film Industry, (Routledge: 2004), which is a study of ticket sales once movies have been released. Some movies disappear from theatres after two or three weeks and fail to earn a profit. Others stay alive for two or three months or more and break even or earn modest profits. A few “go viral” as the kids say these days, and become blockbuster hits.

The point of this exercise, then, is to treat texts themselves as Cultural Beings having a kind of life – cultural – in society. Such beings circulate among people where they live (remain in circulation) or die (no longer circulate). They have specific forms, supported by specific modes of computation, and these change and evolve over decades, centuries, and millennia of literary history. On a much different time scale, that of seconds, minutes, and hours, they these cultural beings come to life in the minds of individuals and groups – think of the people gathered to hear the performance of an oral epic, see plays by Sophocles or Molière, or watch a movie.

At this point we have gone far beyond the implications of our first diagram. That diagram is about human psychology, the psychology of naked apes. If we are going to understand how literature works in the mind and society, then we must understand and work with that psychology. But we must also conceive of these texts as giving rise to cultural beings and those beings have an entire “ecology” that we must understand. That’s what the second diagram is about.

References

[1] Cognitive Science and Literary Theory. Dissertation, Department of English, SUNY at Buffalo, 1978.

[2] The Jasmine Papers: Notes on the Study of Poetry in the Age of Cognitive Science (2013), URL: https://www.academia.edu/8978606/The_Jasmine_Papers_Notes_on_the_Study_of_Poetry_in_the_Age_of_Cognitive_Science

On the Poverty of Cognitive Criticism and the Importance of Computation and Form (2015), URL: https://www.academia.edu/15395772/On_the_Poverty_of_Cognitive_Criticism_and_the_Importance_of_Computation_and_Form

[3] I cover this lack of interest in On the Poverty of Cognitive Criticism (see previous note). My critique of literary Darwinism concentrates on other issues: On the Poverty of Literary Darwinism (2015), URL: https://www.academia.edu/15853288/On_the_Poverty_of_Literary_Darwinism

[4] I’ve written quite a bit about cultural evolution, formally, but more informally. I’ve tagged blog posts on the subject with “cultural evolution”, URL: http://new-savanna.blogspot.com/search/label/cultural%20evolution

I’ve also posted a number of working papers to Academia.edu (and some formal publications), URL: https://independent.academia.edu/BillBenzon/Cultural-Evolution

[5] You can find accounts of my terminology in the various sources listed in note [4], but I’ve collected the terms themselves, along with brief characterizations, in a note, Cultural Evolution Terms: http://new-savanna.blogspot.com/p/glossary-of-terms-for-cultural-evolution.html

[6] My most recent thinking on description: Description 3: The Primacy of Visualization, URL: https://www.academia.edu/16835585/Description_3_The_Primacy_of_Visualization

[7] For a discussion see, The Evolution of Narrative and the Self, Journal of Social and Evolutionary Systems, 16(2): 129-155, 1993. URL: https://www.academia.edu/235114/The_Evolution_of_Narrative_and_the_Self

You work has been gang busters! Yay!

ReplyDelete