Tuesday, October 31, 2017

Numeracy is cultural, not natural

What seems innate and shared between humans and other animals is not this sense that the differences between 2 and 3 and between 152 and 153 are equivalent (a notion central to the concept of number) but, rather, a distinction based on relative difference, which relates to the ratio of the two quantities. It seems we never lose that instinctive basis of comparison. ‘Despite abundant experience with number through life, and formal training of number and mathematics at school, the ability to discriminate number remains ratio-dependent,’ said Fias.What this means, according to Núñez, is that the brain’s natural capacity relates not to number but to the cruder concept of quantity. ‘A chick discriminating a visual stimulus that has what (some) humans designate as “one dot” from another one with “three dots” is a biologically endowed behaviour that involves quantity but not number,’ he said. ‘It does not need symbols, language and culture.’‘Much of the “nativist” view that number is biologically endowed,’ Núñez added, ‘is based on the failure to distinguish at least these two types of phenomena relating to quantity.’ The perceptual rough discrimination of stimuli differing in ‘numerousness’ or quantity, seen in babies and in other animals, is what he calls quantical cognition. The ability to compare 152 and 153 items, in contrast, is numerical cognition. ‘Quantical cognition cannot scale up to numerical cognition via biological evolution alone,’ Núñez said.

Monday, October 30, 2017

Ta-Nehisi Coates • Public Intellectual • On the Dark Side

A new working paper. Title above, abstract, contents, and introduction below.

Download at Academia.edu.: https://www.academia.edu/35000608/Ta-Nehisi_Coates_Public_Intellectual_on_the_Dark_Side

Abstract: Inspired by online conversations between Glenn Loury and John McWhorter, I examine the negative message of Ta-Nehisi Coates though comparisons with Malcolm X, James Baldwin, and Barack Obama. Coates has allowed himself to become trapped in the limits of his own experience and uses his intense curiosity about and formidable knowledge of history to mythologize those limitations, elevating them to a near scriptural intensity.

CONTENTS

Introduction: Ta-Nehisi Coates, a failure of imagination 2

McWhorter on Antiracism as Religion, and Beyond 5

Ta-Nehisi Coates, Malcolm X, Game Theory, and Expressive Culture 10

Felix Culpa: The Judeo-Christian Underpinnings of Coates’ Reparations Argument 14

Another take on Coates: As Writer, as Celebrity 19

Coates, Baldwin, Obama and Expressive Culture 20

Coates, Baldwin, Obama and Expressive Culture 2 24

RESET on Coates, Reparations, Wisdom 28

Appendix 1: Lincoln’s Second Inaugural 30

Appendix 2: America’s Original Sin 32

Introduction: Ta-Nehisi Coates, a failure of imagination

Two years ago Glenn Loury and John McWhorter were talking about Ta-Nehisi Coates on Bloggingheads.tv [1]. I watched, I listened, I blogged. I’ve collected those posts in this document.

More recently Thomas Chatterton Williams published “How Ta-Nehisi Coates Gives Whiteness Power” in the Op-Ed section of The New York Times [2]. The article was occasioned by the publication of Coates’s most recent book, We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, which is a collection of essays. As Williams’s views resonated with my own, and with those earlier observations of Loury and McWhorter, I posted a link to my Facebook page [3] and went on about my business, figuring that would get about as much commentary as most things I link to my page, little to none.

Wrong! I should have know better, but I didn’t, and I found myself under attack.

One of my interlocutors talked of Coates speaking from “his truth”. That I fear, is the problem. Coates has allowed himself to become trapped in his own life. But his life is not the measure of all lives, not even the measure of all black lives. Nor is my life, nor anyone else’s life. That’s one of the purposes of education, to learn to see, think, feel, and imagine beyond the limits of one’s own experience. As I replied to my interlocutor:

Coates was born in 1975, 11 years after the Civil Rights of 64, 10 years after the Voting Rights Act of 65. Yet he writes as though those things had never happened, as though they didn't play a role in making his career possible. Did that legislation accomplish everything? Of course not. Did it accomplish something? Yes. When Coates makes his own personal experience paramount, that's a profound failure of imagination in someone who gets paid for his imaginative powers. He's writing like it was 1950, not 2017.

Writing in Vox [4], Ezra Klein quoted from a recent conversation between Coates and Stephen Colbert:

“You’ve had a hard time in some interviews expressing a sense of hope in this country,” Colbert said. “Do you have any hope tonight for the people out there, about how we could be a better country, we could have better race relations, we could have better politics?”“No,” Coates replied. "But I’m not the person you should go to for that. You should go to your pastor. Your pastor provides you hope. Your friends provide you hope.”This wasn’t the answer Colbert was looking for. “I’m not asking you to make shit up,” he said. “I’m asking if you personally see any evidence for change in America.”“But I would have to make shit up to actually answer that question in a satisfying way,” Coates shot back.

Really?

I’m reminded of some of Dan Everett’s remarks about living among the Pirahã [5]. He points out that they have a perfectly sensible, if limited, epistemology. If they haven’t personally witnessed it, or know someone who has, then it isn’t real. Thus, when Everett revealed that he personally had never seen this Jesus fellow, nor did he know anyone who had, they laughed at him. How could he believe such nonsense?

But they would have had the same reaction if he had told them about Julius Caesar, Simon Bolivar, Elizabeth I of England, Genghis Khan, or Beyoncé. He doesn’t know any of those people nor does he know anyone who knows them. Thus they are beyond the reach of his personal experience and of the experiences of people he knows. By Pirahã standards, these people don’t exist.

Coates was born in 1975, well after the Civil Rights movement. It’s not real to him in this sense. He doesn’t doubt the historical record–he calls on it repeatedly in his own work. But his personal experience of racism and racial politics is of something that’s unchanging. When he interprets US history through his personal experience, the record of oppression looms large, while the record of change and progress seems, feels, weak and insubstantial. And so he discounts it. It’s not real, it’s a chimera.

He has had a kind of education unavailable to the Pirahã. His ability to read gives him access to a vast range of information about the world that is unavailable to them. But when Coates writes, he choses to subordinate that information to the emotional range of his personal experience. He uses that information to amplify and intensify his experience rather than as a means to extend his sense of possibility beyond that experience.

And what of hope, Ta-Nehisi, what of hope? We know what he says about that, don’t we? “I’m not the person you should go to for that. You should go to your pastor. Your pastor provides you hope.” And yet one of the points that McWhorter makes repeatedly in those discussions with Glenn Loury is the Coates’s writings are treated more like scripture than like statements and arguments about the real world (p. 5). One isn’t to question them, one accepts and believes.

While religion can be and has been a vehicle for hope – the Civil Rights Movement, after all, was propelled from the pulpit – it can also be a vehicle for resignation to and acceptance of one’s powerlessness – are we not all powerless in the face of death? That’s what Coates seems to provide, a way of all but reveling in powerlessness. It is in that way that, in Williams’s formulation, he gives power to whiteness. He concludes that op-ed with these paragraphs:

This summer, I spent an hour on the phone with Richard Spencer. It was an exchange that left me feeling physically sickened. Toward the end of the interview, he said one thing that I still think about often. He referred to the all-encompassing sense of white power so many liberals now also attribute to whiteness as a profound opportunity. “This is the photographic negative of a white supremacist,” he told me gleefully. “This is why I’m actually very confident, because maybe those leftists will be the easiest ones to flip.”However far-fetched that may sound, what identitarians like Mr. Spencer have grasped, and what ostensibly anti-racist thinkers like Mr. Coates have lost sight of, is the fact that so long as we fetishize race, we ensure that we will never be rid of the hierarchies it imposes. We will all be doomed to stalk our separate paths.

References

2. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/06/opinion/ta-nehisi-coates-whiteness-power.html?smid=fb-share

5. For example, in Dan Everett. Dark Matter of the Mind: The Culturally Articulated Unconscious. University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Sunday, October 29, 2017

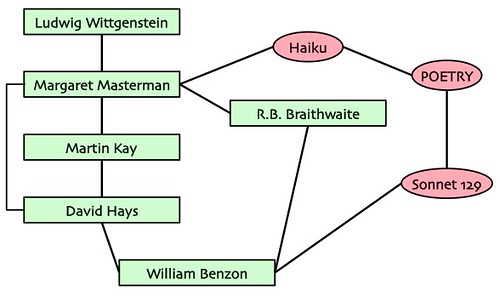

Connections: Wittgenstein ... Lévi-Strauss ... [Shakespeare] ... [Haiku] ... [Jeopardy!]

I’ve recently finished a submission for the First Workshop on the History of Expressive Systems:

By 'expressive systems', we broadly mean computer systems (or predigital procedural methods) that were developed with expressive or creative aims; this is meant to be a superset of the areas called creative AI, expressive AI, videogame AI, computational creativity, interactive storytelling, computational narrative, procedural music, computer poetry, generative art, and more.

And that got me thinking about my intellectual genealogy.

Here’s some notes, some diagrams, and some light commentary, just enough to give some idea of who these people are, how they’re related to one another, to me, and to expressive systems. If you want more information on these people you know what to do.

1° of separation: Core connections

Back in the ancient days Margaret Masterman studied with Ludwig Wittgenstein in the 1930s. Sometime after that she established the Cambridge Language Research Unit (CLRU). She also married R. B. Braithwaite, a philosopher.

Meanwhile David Hays had gotten his degree at Harvard and took a job at the RAND Corporation, where he headed up the machine translation program starting in the mid-1950s. It is through MT, presumably, that he came to know Masterman, whose CLRU was doing important work in linguistic computing. Martin Kay had taken a job there in 1958 and Hays hired him to work for the RAND MT program in 1961.

In the late 1960s the CLRU had done some work on a Haiku generator – that’s Masterman’s connection with expressive computing. Meanwhile she had written a now classic essay on Kuhn’s concept of a paradigm, “The Nature of a Paradigm”. I read that sometime in the early 1970s and was quite impressed; she catalogued 22 different senses in which Kuhn had used the word.

But before that, I had taken a course in decision theory taught by Braithwaite. He was visiting at Johns Hopkins in 1968-69 and, as a philosophy major, I was urged to take the course. We were given that he was a major figure. Also a bit eccentric. I knew nothing about his relationship with Masterman, nor do I learn anything about her relationship with him when I read the Kuhn essay. Those were different worlds and different people.

By the mid-1970s I was at SUNY Buffalo and working with David Hays and his students in computational linguistics. In particular, I was working on Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129, “The Expense of Spirit.” That’s my connection with expressive computing. I didn’t implement anything, but I took a computational view in the kinds of things expressive computing is about.

One day I was at Hays’s house – perhaps working on putting out an issue of the American Journal of Computational Linguistics (AJCL) – and we were talking about things and stuff. He said that he’d had in interesting and possibly important idea about consciousness, but that it was so crazy he was reluctant to tell it to anyone for fear they’d think he’d gone off the deep end. There was, however, one person he trusted.

Who?And then he told me about her and computational linguistics and Martin Kay – I already knew about him; he typeset some pages of AJCL on his Xerox Alto (he was working at PARC at the time) – but I didn’t know about Masterman. He also informed me that she was the one who knitted that white sweater he wore so often in cool weather. I suppose that’s when I learned that she was married to Braithwaite.

Margaret Masterman.

Margaret Masterman! You mean THE Margaret Masterman?

Yes.

Friday, October 27, 2017

Abstract Patterns in Stories – We’re swimming in The Singularity [#DH]

I’m submitting a paper to the first Workshop on the History of Expressive Systems (HEX01), November 14, 2017.

Title: Abstract Patterns in Stories: From the intellectual legacy of David G. Hays

You may download the draft here:

Abstract, Table of Contents, and Conclusion below.

Abstract

Contents

1957: Sputnik, Frye, and Chomsky 1

Computing “Kubla Khan” 2

Abstract concepts as patterns over stories 3

Reading Shakespeare 7

Reworking the model 7

The Expense of Spirit 8

Prospero or bust 11

In search of ring-form texts 12

The singularity is now 15

References 16

The singularity is now

Title: Abstract Patterns in Stories: From the intellectual legacy of David G. Hays

You may download the draft here:

- Academia.edu: https://www.academia.edu/34975666/Abstract_Patterns_in_Stories_From_the_intellectual_legacy_of_David_G._Hays

- SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=3060605

- Research Gate: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320673318_Abstract_Patterns_in_Stories_From_the_intellectual_legacy_of_David_G_Hays

Abstract, Table of Contents, and Conclusion below.

* * * * *

Abstract

Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” exhibits nested structures suggesting an underlying computational process. Seeking to understand that process I joined the computational linguistics research group of David G. Hays in 1974, which was investigating a scheme whereby abstract concepts were defined over patterns in stories. Hays examined concepts of alienation; Mary White examined the beliefs of a millenarian community; and Brain Phillips implemented a system that analyzed short stories for the theme of tragedy. I examined Shakespeare’s sonnet 129, “The Expense of Spirit”, but was unable to apply the system to “Kubla Khan”. In 1976 Hays and I imagined a future system capable of ‘reading’ a Shakespeare play in some non-trivial manner. Such a system had not yet materialized, nor is it in the foreseeable future. Meanwhile, I have been identifying texts and films that exhibit ring-composition, which is similar to the nesting evident in “Kubla Khan”. Do any story generators produce such stories?

Contents

1957: Sputnik, Frye, and Chomsky 1

Computing “Kubla Khan” 2

Abstract concepts as patterns over stories 3

Reading Shakespeare 7

Reworking the model 7

The Expense of Spirit 8

Prospero or bust 11

In search of ring-form texts 12

The singularity is now 15

References 16

The singularity is now

Let’s go back to the beginning. As a child my imagination was shaped by Walt Disney, among others. Disney, as you know, was an optimist who believed in technology and in progress. He had one TV program about the wonders of atomic power, where, alas, things haven’t quite worked out the way Uncle Walt hoped. But he also evangelized for space travel. That captured my imagination and is no doubt, in part, why I became a fan of NASA. I also watched The Jetsons, a half-hour cartoon show set in a future where everyone was flying around with personal jetpacks. And then there’s Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which came out in 1969, which depicted manned flight to near-earth orbit as routine. In the reality of 2017 that’s not the case, nor do we have a computer with the powers of Kubrick’s HAL. On the other hand, we have the Internet and social media; neither Disney, nor the creators of The Jetsons, nor Stanley Kubrick anticipated that.

The point is that I grew up anticipating a future filled with wondrous technology. By mid-1950s standards, yes, we do have wondrous technology. Just not the wondrous technology that was imagined back then. One bit of wondrous future technology has been looming large for several decades, the super-intelligent computer. I suppose we can think of HAL as one instance of that. There are certainly others, such as the computer in the Star Trek franchise, not to mention Commander Data. For the last three decades Ray Kurzweil has been promising such a marvel under the rubric of “The Singularity”. He’s not alone in that belief.

Color me skeptical.

But here’s how John von Neumann used the term: “The accelerating progress of technology and changes in the mode of human life, give the appearance of approaching some essential singularity in the history of the race beyond which human affairs, as we know them, could not continue” [28]. Are we not there? Major historical movements are not caused by point events. They are the cumulative effect of interacting streams of intellectual, cultural, social, political, and natural processes. Think of global warming, of international politics, but also of technology, space exploration – Voyager 1 has left the solar system! – and the many ways we can tell stories that didn’t exist 150 years ago. Have we not reached a point of no return?

The future is now. Oh, I’m sure there are computing marvels still to come. Sooner or later we’re going to figure out how to couple Old School symbolic computing with the current suite of machine learning and neural net technologies and trip the lights fantastic in ways we cannot imagine. That day will arrive more quickly if we concentrate on the marvels we have at hand rather than trying to second guess the future. We are living in the singularity.

Thursday, October 26, 2017

Don't let your kids play bongos. It's bad for their health.

Remember parents: bongos are always the gateway drug. pic.twitter.com/SMbyUW7nmk— Ted Gioia (@tedgioia) October 26, 2017

Searle almost blows it on computational intelligence, almost, but not quite [biology]

John Searle has long been a critic of the pretensions of artificial intelligence to, well, you know, intelligence. He’s perhaps best know for his Chinese room argument. To parody:

Some guy’s in a room. Knows English well but doesn’t speak a lick of Mandarin. But he’s got a flotilla of yellow pads on which there’s a blizzard of instructions in English and pseudo-code for writing Mandarin. A Chinese speaker slips some statement in Mandarin through a slot in the wall. The guy goes to work with his yellow pads and blue pencils and, in due course, scribbles some Mandarin on a slip of paper and sends it back out through the slot. And thus begins a convincing ‘conversation’ in Mandarin. But, really, our guy doesn’t know a jot of Mandarin.

In Searle’s terms what our guy is doing is all syntax, no semantics. And that’s what computers do, all syntax, but not a hint of semantics.

I wasn’t convinced back then – a lot of people weren’t – and I retain that old skepticism, though there are days when I think the argument might have some merit, under a particular interpretation.

Anyhow, I just came across a 2014 article in The New York Review of Books in which Searle takes on two recent books:

Luciano Floridi, The 4th Revolution: How the Infosphere Is Reshaping Human Reality, Oxford University Press, 2014.Nick Bostrom, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies, Oxford University Press, 2014.

Searle’s argument depends on understanding that both objectivity and subjectivity can be taken in ontological and epistemological senses. I’m not going to recount that part of the argument. If you’re curious what Searle’s up in this business to you can read his full argument and/or you can read the appendix to this post, where I’ve quoted a number of passages from a 1995 book in which Searle lays out matters with some care.

Searle sets up his argument by pointing out that, at the time Turing wrote his famous article, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”, the term “computer” originally applied to people (generally women, BTW) who performed computations. The term was then transferred to the appropriate machines via the intermediary, “computing machinery”. Searle observes:

But it is important to see that in the literal, real, observer-independent sense in which humans compute, mechanical computers do not compute. They go through a set of transitions in electronic states that we can interpret computationally. The transitions in those electronic states are absolute or observer independent, but the computation is observer relative. The transitions in physical states are just electrical sequences unless some conscious agent can give them a computational interpretation.This is an important point for understanding the significance of the computer revolution. When I, a human computer, add 2 + 2 to get 4, that computation is observer independent, intrinsic, original, and real. When my pocket calculator, a mechanical computer, does the same computation, the computation is observer relative, derivative, and dependent on human interpretation. There is no psychological reality at all to what is happening in the pocket calculator.

And that, believe it or not, is his argument. Oh he develops it, but really, that’s it, right there.

It seems rather like a semantic quibble that completely misses the substantive issue: can ‘intelligence’ and/or ‘consciousness’ be constructed from the kinds of circuits we use to build digital computers? Assume, for the sake of argument, that it can be done. Who the hell cares what we humans call it or attribute to it, the fact of the matter is that it’s now arguing the point with us. For all I know it might even argue that, no, it’s not intelligent; it’s all syntax, no semantics. Ain’t that a fine kettle of fish?

Return to Searle:

Except for the cases of computations carried out by conscious human beings, computation, as defined by Alan Turing and as implemented in actual pieces of machinery, is observer relative. The brute physical state transitions in a piece of electronic machinery are only computations relative to some actual or possible consciousness that can interpret the processes computationally.

See what I mean?

[And what if we choose to talk of computation in some sense other than that defined by Turing?]

Wednesday, October 25, 2017

Mars or bust, maybe bust

Scott Kelly had spent 520 continuous days in earth orbit, the longest of any NASA astronaut. He's a guinea pig in an experiment to test human ability to live in space in preparation for a trip to Mars. It's not looking good.

I've spent 340 days alongside Russian astronaut Mikhail "Misha" Kornienko on the International Space Station (ISS). As part of NASA's planned journey to Mars, we're members of a program designed to discover what effect such long-term time in space has on human beings. This was my fourth trip to space, and by the end of the mission I'd spent 520 days up there, more than any other NASA astronaut. Amiko has gone through the whole process with me as my main support once before, when I spent 159 days on the ISS in 2010-11. I had a reaction to coming back from space that time, but it was nothing like this.I struggle to get up. Find the edge of the bed. Feet down. Sit up. Stand up. At every stage I feel like I'm fighting through quicksand. When I'm finally vertical, the pain in my legs is awful, and on top of that pain I feel a sensation that's even more alarming: it feels as though all the blood in my body is rushing to my legs, like the sensation of the blood rushing to your head when you do a handstand, but in reverse.I can feel the tissue in my legs swelling. I shuffle my way to the bath room, moving my weight from one foot to the other with deliberate effort. Left. Right. Left. Right. I make it to the bathroom, flip on the light, and look down at my legs. They are swollen and alien stumps, not legs at all. "Oh shit," I say. "Amiko, come look at this." She kneels down and squeezes one ankle, and it squishes like a water balloon. She looks up at me with worried eyes. "I can't even feel your ankle bones," she says."My skin is burning, too," I tell her. Amiko frantically examines me. I have a strange rash all over my back, the backs of my legs, the back of my head and neck – everywhere I was in contact with the bed. I can feel her cool hands moving over my inflamed skin. "It looks like an allergic rash," she says. "Like hives."I use the bathroom and shuffle back to bed, wondering what I should do. Normally if I woke up feeling like this, I would go to the emergency room. But no one at the hospital will have seen symptoms of having been in space for a year. I crawl back into bed, trying to find a way to lie down without touching my rash.I can hear Amiko rummaging in the medicine cabinet. She returns with two ibuprofen and a glass of water. As she settles down, I can tell from her every movement, every breath, that she is worried about me. We both knew the risks of the mission I signed on for. After six years together, I can understand her perfectly, even in the wordless dark.

Walking in space:

I didn't get to spend time outside the station until my first of two planned space walks, which was almost seven months in. This was one of the things that some people found difficult to imagine about living on the space station, the fact that I couldn't step outside when I felt like it. Putting on a spacesuit and leaving the station for a space walk was an hours-long process that required the full attention of at least three people on station and dozens more on the ground.Space walks were the most dangerous thing we did in orbit. Even if the station was on fire, even if it was filling up with poison gas, even if a meteoroid had crashed through a module and outer space was rushing in, the only way to escape the station was in a Soyuz capsule, which also needed preparation and planning to depart safely. We practised dealing with emergency scenarios regularly, and in many of these drills we raced to prepare the Soyuz as quickly as we could. No one had ever had to use the Soyuz as a lifeboat, and no one hoped to.

Back on earth:

I tell my flight surgeon, Steve, that I feel well enough to get right to work immediately upon returning from space, and I do, but within a few days I feel much worse. This is what it means to have allowed my body to be used for science. I will be a test subject for the rest of my life. A few months after arriving back on Earth, though, I feel distinctly better. I've been travelling the country and the world talking about my experiences in space. It's gratifying to see how curious people are about my mission, how much children instinctively feel the excitement and wonder of space flight, and how many people think, as I do, that Mars is the next step.I also know that if we want to go to Mars, it will be very, very difficult, it will cost a great deal of money and it may likely cost human lives. But I know now that if we decide to do it, we can.

Tuesday, October 24, 2017

Unlike classical musicians, jazz musicians expect the unexpected

Eric Dolan in PsyPost reports on research done at Wesleyan University:

The researchers used EEG to compare the electrical brain activity of 12 Jazz musicians (with improvisation training), 12 Classical musicians (without improvisation training), and 12 non-musicians while they listened to a series of chord progressions. Some of the chords followed a progression that was typical of Western music, while others had an unexpected progression.Louie and her colleagues found that Jazz musicians had a significantly different electrophysiological response to the unexpected progression, which indicated they had an increased perceptual sensitivity to unexpected stimuli along with an increased engagement with unexpected events.“Creativity is about how our brains treat the unexpected,” Loui told PsyPost. “Everyone (regardless of how creative) knows when they encounter something unexpected. But people who are more creative are more perceptually sensitive and more cognitively engaged with unexpectedness. They also more readily accept this unexpectedness as being part of the vocabulary.“This three-stage process: sensitivity, engagement, and acceptance, occurs very rapidly, within a second of our brains encountering the unexpected event. With our design we can resolve these differences and relate them to creative behavior, and I think that’s very cool.”

Here's the abstract of the research report (paywall):

Emily Przysinda, Tima Zeng, Kellyn Maves, Cameron Arkin, Psyche Loui. Jazz musicians reveal role of expectancy in human creativity. Brain and Cognition. Volume 119, December 2017, Pages 45-53, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2017.09.008Abstract: Creativity has been defined as the ability to produce work that is novel, high in quality, and appropriate to an audience. While the nature of the creative process is under debate, many believe that creativity relies on real-time combinations of known neural and cognitive processes. One useful model of creativity comes from musical improvisation, such as in jazz, in which musicians spontaneously create novel sound sequences. Here we use jazz musicians to test the hypothesis that individuals with training in musical improvisation, which entails creative generation of musical ideas, might process expectancy differently. We compare jazz improvisers, non-improvising musicians, and non-musicians in the domain-general task of divergent thinking, as well as the musical task of preference ratings for chord progressions that vary in expectation while EEGs were recorded. Behavioral results showed for the first time that jazz musicians preferred unexpected chord progressions. ERP results showed that unexpected stimuli elicited larger early and mid-latency ERP responses (ERAN and P3b), followed by smaller long-latency responses (Late Positivity Potential) in jazz musicians. The amplitudes of these ERP components were significantly correlated with behavioral measures of fluency and originality on the divergent thinking task. Together, results highlight the role of expectancy in creativity.

Monday, October 23, 2017

The Hunt for Genius Part 3: Cultural Factors

Here's another reposting from my series on the MacArthur Fellowship Program. This time it's a short one in which I take a quick look at cultural factors. We live in a world that's rapidly changing, but the Big Mac Lottery Board pretty much assumes the future's going to be like the past. I've collected these posts into a working paper, The Genius Chronicles: Going Boldly Where None Have Gone Before?, which you may download at this link:

https://www.academia.edu/7974651/The_Genius_Chronicles_Going_Boldly_Where_None_Have_Gone_Before

It does look like this topic has taken over my brain, at least a part of it, for a while. Things are condensing and compacting. Processing goes on.

https://www.academia.edu/7974651/The_Genius_Chronicles_Going_Boldly_Where_None_Have_Gone_Before

* * * * *

It does look like this topic has taken over my brain, at least a part of it, for a while. Things are condensing and compacting. Processing goes on.

My main point remains: The MacArthur Fellows Program is strongly biased by the social network in which it is situated. The simplest thing it can do to blunt that bias and thereby name more interesting and challenging classes of fellows is to stop giving awards to people on staff at elite institutions. Those institutions are too deeply rooted in the past to serve the future well.

Our World is Culturally Complex and Changing

First, while the search for genius, as conducted by the MacArthur Fellows Program for example, is conceptualized as a search for attributes of individuals, even an essence, that’s not how it works out in fact and in our world. If our world were culturally uniform and static, then, yes, the search for genius might properly be conceptualized as a search for essence. But that’s only because every individual would be surrounded by the same culture and thus the possibilities for a ‘fit’ between individual capabilities and accomplishments would be the same for all.

But that’s not the world we live in. In the first place, it is not culturally uniform. Culture varies by class, geographical region, and by ethnicity and religion. In such a world a search for genius will almost inevitably be biased by the interests and understanding for those conducting the search. In such a world the ONLY way to escape bias is to recognize the problem and take explicit steps to correct for it.

Just what those steps would be, I don’t know. Two obvious suggestions: 1) Make sure the selection process includes people from all sectors of society. 2) Conceive each class of awardees as a sampling of the cultural space.

And in the second place, our world is not culturally static. It’s changing rapidly for various reasons. Globalization is driving workforce changes that affect educational requirements and skillset distribution and needs. Computer technology has changed the media world and is itself making many jobs obsolete while creating new classes of jobs. Ideas in every sphere are changing and new expressive forms are emerging in the arts. And globalization is moving large numbers of people from one country to another.

In that kind of situation, which is the situation we face, it is all but impossible to have an unbiased genius hunt. I argued in my first post, on the MacArthur Fellows Program, that their search is in fact very biased and that that bias is evident in the number of fellows who are on staff at elite educational and research institutions. While those institutions are pumping out some of the ideas and technology that’s driving change, they are themselves conservative. How could these conservative institutions thus be a force for change?

Sunday, October 22, 2017

Saturday, October 21, 2017

Acting white in the Trump-era

White people acting white have embraced the ethic of the white underclass, which is distinct from the white working class, which has the distinguishing feature of regular gainful employment. The manners of the white underclass are Trump’s — vulgar, aggressive, boastful, selfish, promiscuous, consumerist. The white working class has a very different ethic. Its members are, in the main, churchgoing, financially prudent, and married, and their manners are formal to the point of icy politeness. You’ll recognize the style if you’ve ever been around it: It’s “Yes, sir” and “No, ma’am,” but it is the formality of soldiers and police officers — correct and polite, but not in the least bit deferential. It is a formality adopted not to acknowledge the superiority of social betters but to assert the equality of the speaker — equal to any person or situation, perfectly republican manners. It is the general social respect rooted in genuine self-respect.

Its opposite is the sneering, leveling, drag-’em-all-down-into-the-mud anti-“elitism” of contemporary right-wing populism. Self-respect says: “I’m an American citizen, and I can walk into any room, talk to any president, prince, or potentate, because I can rise to any occasion.” Populist anti-elitism says the opposite: “I can be rude enough and denigrating enough to drag anybody down to my level.” Trump’s rhetoric — ridiculous and demeaning schoolyard nicknames, boasting about money, etc. — has always been about reducing. Trump doesn’t have the intellectual capacity to duke it out with even the modest wits at the New York Times, hence it’s “the failing New York Times.” Never mind that the New York Times isn’t actually failing and that any number of Trump-related businesses have failed so thoroughly that they’ve gone into bankruptcy; the truth doesn’t matter to the argument any more than it matters whether the fifth-grade bully actually has an actionable claim on some poor kid’s lunch money. It would never even occur to the low-minded to identify with anybody other than the bully. That’s what all that ridiculous stuff about “winning” was all about in the campaign. It is might-makes-right, i.e., the politics of chimpanzee troupes, prison yards, kindergartens, and other primitive environments. That is where the underclass ethic thrives — and how “smart people” came to be a term of abuse.

75% Americans are afraid of government corruption

H/t 3QD.For the third year in a row, corruption of government officials has topped the list—only this year it jumped 13 percentage points, from 60.6 percent of Americans identifying themselves as afraid of government corruption in 2016, to a whopping 74.5 percent being afraid of the same in 2017.“Our previous lists had more to do with disasters and crime, and that naturally lent itself to the type of messaging [about crime] we’re doing,” Bader says. “The list this year is fundamentally different in the sense that it’s showing a great fear of some of the things happening in this presidency.”Fear of North Korea using weapons came in at number nine on the list, with 44.9 percent marking themselves as being afraid. The survey has been asking about nuclear attacks since it first started; this is the first year North Korea was listed specifically. “It’s very difficult to curb people’s fears about North Korea when frankly, North Korea and how it’s being addressed is very scary,” says Bader.Another first this year was environmental concerns appearing in the top ten list of fears, of which there were four: pollution of oceans rivers and lakes; pollution of drinking water; global warming/climate change; and air pollution. And the survey was conducted before Hurricanes Harvey and Maria and the ongoing California wildfire crisis, with questions sent out from June 28 to July 7. The researchers ascribe the increased environmental fears to media coverage of President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement and cut funding to the Environmental Protection Agency, as well as coverage of the lead in the tap water in Flint, Michigan.

Ebert Defends Literature on the uncharted seas

Bumping this seven year old post to the top of the queue. The issues are still unresolved. Regert Ebert died on April 4, 2013.

* * * * *

I’ve recently become interested in Roger Ebert. As I’ve indicated earlier, he’s long served me as a reference critic, someone I’d consult on movies that interest me. My current interest extends beyond that.

The nature of my current interest is not entirely clear to me. Oh, sure, Ebert is one of the most prominent intellectuals in America these days, and is readily available on the web. As is Stanley Fish. That Stanley Fish is an intellectual is obvious on the face of it. But Roger Ebert, he’s a film critic, no? Yes, and we don’t normally think of film critics as intellectuals. But there are film critics and there are film critics.

And Roger Ebert is more than a film critic. Perhaps he’s always been more than a film critic. But it’s his writing in his blog that interests me, and that’s what’s prompted me to think of him as an intellectual. Yes, I find it just a bit strange. But I’m going with it. He’s not the type of intellectual Stanley Fish is, but an intellectual he is. And, for what it’s worth, he’s more widely known.

And that’s worth something. Just what, I don’t know. But something, and that something is part of my attraction.

You may have heard that Ebert’s been kicking up a fuss about video games. He doesn’t think that they can ever be art. This little tempest in a teapot led him to Tweet and then blog a simple question: “Which of these would you value more? A great video game. Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain.” The answer came back 13,823 to 8,088 in favor of video games.

And so Ebert posted that result to his blog, while also admitting that there was nothing remotely scientific about his procedure. It’s just an informal question, with an answer that didn’t please him. And he launches into a defense and justification of literature without, however, saying anything more against video games. For the moment, that’s done and gone.

Ebert tells us that he first read Huckleberry Finn when he was seven – I believe I was a bit older than that when my father read it to me. He quotes Hemingway’s line about all modern American literature descending from Huck Finn. [He illustrates his post with scans from a Huck Finn comic.] And he quotes his favorite passage from the book: “Read it over a couple of times and then read it aloud to someone you like. It's music. Can you imagine a more evocative description of a thunderstorm?”

Here’s the nub of his concern:

I believe reading good books is the best way we can civilize ourselves even in the absence of all other opportunities. If a child can read, has access to books and the freedom to read them, that child need not be "disadvantaged" for long. What concerns me is that reading competence and experience has been falling steadily in America. Most of the adults I meet are not very "well read." My parents were.

And then:

Beyond a certain point, we take our education into our own hands. We discover what excites us intellectually, and seek it out. The world of books allows us to walk in the shoes of people who lived in other times and other places, who belonged to other races and religions. It allows us to become more humane and open-minded. In exposing us to prose of the highest level, it encourages us to think in a way that isn't merely "better" but is more fanciful, creative, poetic and expressive. It makes us less boring, and less bore-able.

This is all quite traditional. It could have been written fifty or sixty years ago. No doubt it was, by other intellectuals, in other words.

It’s as though the intellectual ferment that ripped through English departments in the 70s and 80s, ferment in which Stanley Fish was a major rabble rouser, it’s as though that had passed Ebert by. Ebert is writing as a traditional humanist in a world where the academic stewards of humanism have all but abandoned the tradition. The promising new ideas of the 70s and 80s have, indeed, changed the field of discourse. But the way forward is no longer apparent. We’re in a swamp, we have no map, nor compass, and so we don’t know where we’re going.

Yet Ebert defends reading in traditional terms as though Fish’s swamp didn’t exist. What’s particularly interesting is that it’s literature that Ebert is defending, not film. Literature is very important to him, but it’s film that he’s put at the center of his intellectual life. I don’t know what terms he’d use to defend film, though one could certainly say that it allows us to walk in the shoes of people who lived in other times and other places, who belonged to other races and religions. It allows us to become more humane and open-minded. In exposing us to prose of the highest level, it encourages us to think in a way that isn't merely "better" but is more fanciful, creative, poetic and expressive. It makes us less boring, and less bore-able.

Such words, once again, ignore Fish’s swamp. But they’re apt. Moreover it seems to me that we’re living in a world where film has the kind of importance that novels had in the 19th century. In fact, film may be less important now than it was 30, 50, 80 years ago. And video games, I’m told the video game market is bigger than the film market. Do video games allow us to walk in the shoes of people who lived in other times . . . . ? I don’t know, I don’t play them.

So, in consequence of an argument that video games aren’t and will never be art, Roger Ebert, a film critic, mounts a traditional defense of literature. That’s were we are today. That’s our uncharted sea.

Friday, October 20, 2017

It's a small world (network) after all, and it arises through adaptive rewiring

Nicholas Jarman, Erik Steur, Chris Trengove, Ivan Y. Tyukin & Cees van Leeuwen, Self-organisation of small-world networks by adaptive rewiring in response to graph diffusion, Scientific Reports 7, Article number: 13158 (2017) doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12589-9

AbstractComplex networks emerging in natural and human-made systems tend to assume small-world structure. Is there a common mechanism underlying their self-organisation? Our computational simulations show that network diffusion (traffic flow or information transfer) steers network evolution towards emergence of complex network structures. The emergence is effectuated through adaptive rewiring: progressive adaptation of structure to use, creating short-cuts where network diffusion is intensive while annihilating underused connections. With adaptive rewiring as the engine of universal small-worldness, overall diffusion rate tunes the systems’ adaptation, biasing local or global connectivity patterns. Whereas the former leads to modularity, the latter provides a preferential attachment regime. As the latter sets in, the resulting small-world structures undergo a critical shift from modular (decentralised) to centralised ones. At the transition point, network structure is hierarchical, balancing modularity and centrality - a characteristic feature found in, for instance, the human brain.IntroductionComplex network structures emerge in protein and ecological networks, social networks, the mammalian brain, and the World Wide Web. All these self-organising systems tend to assume small–world network (SWN) structure. SWNs may represent an optimum in that they uniquely combine the advantageous properties of clustering and connectedness that characterise, respectively, regular and random networks. Optimality would explain the ubiquity of SWN structure; it does not inform us, however, whether the processes leading to it have anything in common. Here we will consider whether a single mechanism exists that has SWN structure as a universal outcome of self-organisation.In the classic Watts and Strogatz algorithm, a SWN is obtained by randomly rewiring a certain proportion of edges of an initially regular network. Thereby the network largely maintains the regular clustering, while the rewiring creates shortcuts that enhance the networks connectedness. As it shows how these properties are reconciled in a very basic manner, the Watts-Strogatz rewiring algorithm has a justifiable claim to universality. However, the rewiring compromises existing order than to rather develop over time and maintain an adaptive process. Therefore the algorithm is not easily fitted to self-organising systems.In self-organising systems, we propose, network structure adapts to use - the way pedestrians define walkways in parks. Accordingly, we consider the effect of adaptive rewiring: creating shortcuts where network diffusion (traffic flow or information transfer) is intensive while annihilating underused connections. This study generalises previous work on adaptive rewiring. While these studies have shown that SWN robustly emerge through rewiring according to the ongoing dynamics on the network, the claim to universality has been frustrated by need to explicitly specify the dynamics. Here we take a more general approach and replace explicit dynamics with an abstract representation of network diffusion. Heat kernels capture network-specific interaction between vertices and as such they are, for the purpose of this article, a generic model of network diffusion.We study how initially random networks evolve into complex structures in response to adaptive rewiring. Rewiring is performed in adaptation to network diffusion, as represented by the heat kernel. We systematically consider different proportions of adaptive and random rewirings. In contrast with the random rewirings in the Watts-Strogatz algorithm, here, they have the function of perturbing possible equilibrium network states, akin to the Boltzmann machine. In this sense, the perturbed system can be regarded as an open system according to the criteria of thermodynamics.In adaptive networks, changes to the structure generally occur at a slower rate than the network dynamics. Here, the proportion of these two rates is expressed by what we call the diffusion rate (the elapsed forward time in the network diffusion process before changes in the network structure). Low diffusion rates bias adaptive rewiring to local connectivity structures; high diffusion rates to global structures. In the latter case adaptive rewiring approaches a process of preferential attachment.We will show that with progressive adaptive rewiring, SWNs always emerge from initially random networks for all nonzero diffusion rates and for almost any proportion of adaptive rewirings. Depending on diffusion rate, modular or centralised SWN structures emerge. Moreover, at the critical point of phase transition, there exists a network structure in which the two opposing properties of modularity and centrality are balanced. This characteristic is observed, for instance, in the human brain We call such a structure hierarchical. In sum, adaptation to network diffusion represents a universal mechanism for the self–organisation of a family of SWNs, including modular, centralised, and hierarchical ones.

Thursday, October 19, 2017

The Hunt for Genius, Part 2: Crackpots, athletes, 4 kinds of judgment, training, and Cultural Context

I continue reposting my series on the MacArthur Fellowship Program. This time I take up the problem of identifying "genius"-class creativity by running through a variety of examples and ending on a brief discussion of the importance of cultural context. How do we bias our selection process toward the future, not the past? I've collected these posts into a working paper, The Genius Chronicles: Going Boldly Where None Have Gone Before?, which you may download at this link:

https://www.academia.edu/7974651/The_Genius_Chronicles_Going_Boldly_Where_None_Have_Gone_Before.

Part 1 is my post on the misguided MacArthur Fellows Program. And I thought that would be the end of it. I was wrong.

https://www.academia.edu/7974651/The_Genius_Chronicles_Going_Boldly_Where_None_Have_Gone_Before.

* * * * *

Part 1 is my post on the misguided MacArthur Fellows Program. And I thought that would be the end of it. I was wrong.

Now that I’ve gotten my brain revved up thinking about “genius”, whatever that is, I’ve got to think a bit more. The foundation is making judgments about people, judgments about the originality of their work, their ability to cross traditional disciplinary and institutional boundaries, their need for support, and their potential for future contributions of an extraordinary kind. The program has been consistently criticized for picking too many fellows who don’t meet those criteria.

In that post I argued there is in fact a simple way to improve those judgments relative to those criteria: don’t give fellowships to people with stable jobs at elite institutions. The purpose of this post is to clarify my reasoning on that point.

I begin by pointing out that it’s possible for one person to be both a genius and a crackpot. Then I have a brief note on the Nobel Prize, where the point is that even giving awards for accomplishment is difficult. In the following two sections I step through athletic and musical performance as a way of outlining different kinds of judgments, which I’ve called objective, complex, incommensurable, and predictive. I return to the MacArthur Fellowship Program in the final section where I once again talk about the importance of cultural context.

Two for One: Genius and Crackpot in a Single Package

First, let’s think about, say, Isaac Newton, a prototypical scientific genius. We remember him for his work in physics (optics, mechanics, and gravity) and mathematics. No one cares about his work in theology and alchemy except historians, yet it meant a great deal to Newton himself. In the last century Albert Einstein was quickly recognized as a genius, mostly for his work on relativity and photons. He spent the last part of his career looking for a unified field theory. For a long time that work was considered to be a waste of time. Now that unified theory has made a comeback in physics I don’t know whether that work has been re-evaluated or not.

Were these guys working on half a brain when they did that misbegotten work? Were they drunk? I mean, what happened to the supernal abilities that allowed them to make profound and permanent contributions to science?

Nothing happened to those abilities. There’s no reason to think that they weren’t firing on all cylinders when they did that work. The work just doesn’t fit very well with other knowledge of the world. Think of ideas as keys. What do we use keys for? To unlock doors. Some of the keys these geniuses crafted unlocked real doors. Other keys don’t unlock real doors. Whether or not a key unlocks a door is not a matter of how well the key is crafted. The most exquisitely crafted square peg is not going to fit into a round hole.

Well, it turns out that some of the locks these guys had in mind when crafting keys weren’t real. They were figments of their imagination. Just because the lock was imagined by a genius doesn’t mean it is real.

And so forth.

The point is that ability is not enough. That ability has to be fitted to context.

The search for genius, however, is always conceptualized as a search for ability. This is most obviously the case when genius is defined in terms of a score on some standardized test, an IQ test. If you score high enough on the test you’re a genius – as defined by the test. Otherwise, no.

Now, I rather doubt that anyone involved in the MacArthur Fellows program cares about scores on IQ tests. Whatever it is they’re looking for, it can’t be identified by an IQ test. If it could, then running the Fellows Program would be trivially easy. If tests did the trick there’d be no need for the program. The geniuses would be identified by the standard testing programs undertaken in schools. They aren’t.

So, how do you find a genius?

Nobel Prizes: Even Post Facto Judgments are Difficult

What about Nobel Prizes? They, of course, are awarded for accomplishment, not for promise. And so the prize is not conceived of as one given for ability, though we all assume that Nobel Laureates must have extraordinary ability in order to do whatever it is that got them the award.

And yet the fact that these prizes are awarded for accomplishments visible to all doesn’t insulate them from criticism. I’m sure if I were to did around in what’s written about Nobels I’d find lists of people who got them, but shouldn’t (e.g. Obama or Kissinger for the Peace Prize) and other lists of people who should have gotten them but didn’t. Judging the value of accomplishments such as these is not easy.

So, let’s start by thinking about some kind of ability where the tests are straightforward.

Wednesday, October 18, 2017

What WAS I thinking when I snapped this photo? Not the Beatles and not Abbey Road

If you are of a certain age and a certain inclination you can’t help by think of the album cover for Abbey Road, released by the Beatles in 1969. That’s certainly what I thought when I looked at the photo on my computer.

But that’s not what I was thinking when I took the photo. I had come out of New York City’s Penn Station at a bit after 5PM on Saturday, October 14, 2017. I was taking photos to document the day – a train ride my sister had gotten for us in celebration of my upcoming major birthday – and snapping shots in front of the station. Traffic was busy, making photography a bit tricky, everything moving, shots materializing and disappearing just as quickly.

It was shoot or die. I saw those people walking across street and my mind flashed there’s a photo there, but not in so many words. It was just a realization that I had to point and shoot NOW or lose it. So I took the shot.

And moved on, taking other shots.

But I’m sure that intuitive decision had been primed by that album cover I saw so many times over the years, but not, say, in the last five or six, perhaps more, years.

And, you see, when you shoot quickly, sometimes things don’t quite work out. Sometimes that’s OK.

Tuesday, October 17, 2017

Out of the ground with your hands, my summer in coal @3QD

I’ve done a little editing to a recent post and reposted it at 3 Quarks Daily under the title, slightly changed from the original, My summer job working in coal – or, how I learned about class in America: http://www.3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2017/10/my-summer-job-working-in-coal-or-how-i-learned-about-class-in-america.html

It would be a bit strong to say that coal pervaded my life growing up, but I was aware of it and thought about it, in one way or another, almost, perhaps, likely, daily – steel too. After all, my father was in the business and took frequent trips to visit coal mines and cleaning plants. I remember waiting for him to come home, staying up late a night they day of his return, and getting the little gifts he’d bring me and my sister from whatever exotic place he’d visited. I remember the hard hats he wore when on site.

And I remember talking with him about his work. I remember him telling me about dead plant matter turning into peat, peat into lignite and lignite into coal. Coal was once living matter.

Coal is elemental. It’s a fuel, a dirty fuel. A dirty fuel that gave us the iron and steel industries. Coal fires gave us the Anthropocene.

Ashes to Dust

Life to Coal

Coal to Ashes

Dust to Life

Monday, October 16, 2017

Another (strenuous) take on what went wrong with literary criticism, John Searle and Geoffrey Hartman edition

Yeah, I know. But it’s important to get this right.

Once again I’m going to review that Geoffrey Hartman statement I find so characteristic of the mid-1970s rearward shift in academic literary criticism, the one about ‘rithmatic and distance. But this time I want to put it in the context a discussion of the ontological and epistemological senses of objective and subjective that John Searle makes in The Construction of Social Reality, Penguin Books, 1995.

Searle: Ontology and Epistemology

After some preliminary discussion, some of which I’ve appended to this post, Searle concludes (p. 7):

Here, then, are the bare bones of our ontology: We live in a world made up entirely of physical particles in fields of force. Some of these are organized into systems. Some of these systems are living systems and some of these living systems have evolved consciousness. With consciousness comes intentionality, the capacity of the organism to represent objects and states of affairs in the world to itself. Now the question is, how can we account for the existence of social facts within that ontology?

How indeed.

Searle then observes (pp. 7-8):

Much of our world view depends on our concept of objectivity and the contrast between the objective and the subjective. Famously, the distinction is a matter of degree, but it is less often remarked that both “objective” and “subjective” have several different senses. For our present discussion two senses are crucial, an epistemic sense of the objective-subjective distinction and an ontological sense. Epistemically speaking, “objective” and “subjective “ are primarily predicates of judgments. We often speak of judgments as being “subjective” when we mean that their truth or falsity cannot be settled “objectively,” because the truth or falsity is not a simple matter of fact but depends on certain attitudes, feelings, and points of view of the makers such subjective judgments with objective judgments, such as the judgment “Rembrandt lived in Amsterdam during the year 1632.” For such objective judgments, the facts in the world that make them true or false are independent of anybody’s attitudes or feelings about them. In this epistemic sense we can speak not only of objective judgments but of objective facts. Corresponding to objectively true judgments there are objective facts. It should be obvious from these examples that the contrast between epistemic objectivity and epistemic subjectivity is a matter of degree.In addition to the epistemic sense of the objective-subjective distinction, there is also a related ontological sense. In the ontological sense, “objective” and “subjective” are predicates of entities and types of entities, and they ascribe modes of existence. In the ontological sense, pains are subjective entities, because their mode of existence depends on being felt by subjects. But mountains, for example, in contrast to pains, are ontologically objective because their mode of existence is independent of any perceiver or any mental state.

Word meanings, in this sense, are ontologically subjective, which I’ve previously argued [1]. And so are the meanings of texts, even texts about objective facts. Hence textual meaning can be subject to endless, and often fruitless, discussion, especially when intersubjective agreement on the meanings of crucial terms is lax.

Continuing directly on from the previous passage, (pp. 8-9):

We can see the distinction between the distinctions clearly if we reflect on the fact that we can make epistemically subjective statements about entities that are ontologically objective, and similarly, we can make epistemically objective statements about entities that are ontologically subjective. For example, the statement “Mt. Everest is more beautiful than Mt. Whitney” is about ontologically objective entities, but makes a subjective judgment about them. On the other hand, the statement “I now have a pain in my lower back” reports an epistemically objective fact in the sense that it is made true by the existence of an actual fact that is not dependent on any stance, attitudes, or opinions of observers. However, the phenomenon itself, the actual pain, has a subjective mode of existence.

I argue, though Searle might disagree, that the meanings of the words in that statement – “I now have a pain in my lower back” – are themselves ontologically subjective, despite the fact that the statement itself, in context, is ABOUT an epistemologically objective fact (where that fact is about something ontologically subjective, a pain).

It’s confusing, I know. Alas, it’s going to get worse.

Sunday, October 15, 2017

Latour on the second science "war"

Jop de Vrieze interviews Bruno Latour in Science; an excerpt:

Q: How do you look back at the “science wars”?

A: Nothing that happened during the ’90s deserves the name “war.” It was a dispute, caused by social scientists studying how science is done and being critical of this process. Our analyses triggered a reaction of people with an idealistic and unsustainable view of science who thought they were under attack. Some of the critique was indeed ridiculous, and I was associated with that postmodern relativist stuff, I was put into that crowd by others. I certainly was not antiscience, although I must admit it felt good to put scientists down a little. There was some juvenile enthusiasm in my style.We’re in a totally different situation now. We are indeed at war. This war is run by a mix of big corporations and some scientists who deny climate change. They have a strong interest in the issue and a large influence on the population.

Q: How did you get involved in this second science war?

A: It happened in 2009 at a cocktail party. A famous climate scientist came up to me and said: “Can you help us? We are being attacked unfairly.” Claude Allègre, a French scientist and former minister of education, was running a very efficient ideological campaign against climate science.It symbolized a turnaround. People who had never really understood what we as science studies scholars were doing suddenly realized they needed us. They were not equipped, intellectually, politically, and philosophically, to resist the attack of colleagues accusing them of being nothing more than a lobby.

Q: How do you explain the rise of antiscientific thinking and “alternative facts”?

A: To have common facts, you need a common reality. This needs to be instituted in church, classes, decent journalism, peer review. … It is not about posttruth, it is about the fact that large groups of people are living in a different world with different realities, where the climate is not changing.The second science war has at least freed us of the idea that science and technology can be separated from policy. I have always argued that they can't be. Science has never been immune to political bias. On issues with huge policy implications, you cannot produce unbiased data. That does not mean you cannot produce good science, but scientists should explicitly state their interests, their values, and what sort of proof will make them change their mind.

Q: How should scientists wage this new war?

H/t 3QD.A: We will have to regain some of the authority of science. That is the complete opposite from where we started doing science studies. Now, scientists have to win back respect. But the solution is the same: You need to present science as science in action. I agree that’s risky, because we make the uncertainties and controversies explicit.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)