Wednesday, March 28, 2018

Patterns and Literature

From four years ago.So, patterns. Some patterns operate on the time and scale of sensory perception; we see, hear, smell, touch, and taste things in the course of everyday life. But other patterns require more time and deliberation. That our solar system consists of planets and asteroids in transit about the sun is a pattern, but it’s not one given in sensory perception. Rather, it’s one that can be inscribed on a surface (where on can see it at human scale) and that emerged through thousands upon thousands of observations made by hundreds of individuals conversing over the course of centuries.

Literary texts (and films) are a bit like that. They are devices for capturing patterns of (mostly, generally) human life. Depending on the text, the reading may take only minutes or hours, perhaps over the course of days, but the writing likely took longer. Each text rests on a history of texts from which it draws and against which it reacts, and a body of texts requires a community to keep it in circulation.

Lifeways and Literature

Susan Langer (Feeling and Form) would say that these textual patterns embody virtual experience. Wayne Booth (The Company We Keep) talks of literature as a way of “trying out” modes of life, while more recently, Keith Oatley (Such Stuff as Dreams) writes of literary experience as simulation. We can say that these patterns are meant to be taken up by one’s whole psyche, one’s whole being – even that they are meant to facilitate unity of being.

Kenneth Burke writes of this in “Literature as Equipment for Living” from The Philosophy of Literary Form (1973). Using words and phrases from several definitions of the term “strategy” (in quotes in the following passage), he asserts that (p. 298):

... surely, the most highly alembicated and sophisticated work of art, arising in complex civilizations, could be considered as designed to organize and command the army of one’s thoughts and images, and to so organize them that one “imposes upon the enemy the time and place and conditions for fighting preferred by oneself.” One seeks to “direct the larger movements and operations” in one's campaign of living. One “maneuvers,” and the maneuvering is an “art.”

Finally, it is not, after all, as though life happens OVER THERE, while literature takes place in a separate space IN HERE such that literature is completely external to life. It’s not that simple. Literature takes place in and reacts on life.

Interpretive Criticism

Provisionally, we can say that a text represents certain states of affairs in the world; call that content. Texts use various devices to organize their contents; call that form. In Oatley’s terms the content is the world simulated while the form is the “machinery” used to run the simulation.

In critical practice, distinguishing form and content can be difficult. Ordinary literary criticism, mainstream literary criticism, is focused on interpretation. As far as I can tell, that seems to be an exercise in re-stating the lifeways captured in a text in a different kind of language. Such interpretations are always partial; they always leave some aspects of a text untouched. And while hermeneutic criticism takes note of textual devices, of formal matters, that is not its focus. It attends to form as a way of explicating meaning, of retracing the lifeways originally traced in the text.

I would further say that such criticism strives to keep in touch with the “ordinary” practice of reading and “taking up” literature. Hence it is common to talk of an interpretation as a reading of the text. The introduction of technical and quasi-technical concepts and vocabulary tends to get in the way of such reading and hence is problematic. On the one hand we hear calls for critics to drop the scientism, as this is thought to be, and write in ordinary language. On the other hand, critics themselves feel and express anxiety about their activity, thinking of it as somehow parasitic on primary texts and not an activity unto itself–I’m thinking here of the anxieties Geoffrey Hartman expresses in The Fate of Reading.

But it can be parasitic only if it is (seen as) doing the same thing as literature; it the aim is to do something different, well then, it’s no longer parasitic. Biology, for example, needs living things as its objects of investigation; but no one would think of biology as parasitic upon life. And so literary criticism needs texts as objects of investigation. It is only to the extent that criticism aims, not at the texts, but through the texts to life itself, that it can be parasitic.

Monday, March 26, 2018

Population is the main driver of war group size and conflict casualties

Rahul C. Oka, Marc Kissel, Mark Golitko, Susan Guise Sheridan, Nam C. Kim and Agustín Fuentes, Population is the main driver of war group size and conflict casualties, PNAS December 11, 2017. 201713972; published ahead of print December 11, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1713972114

Significance: Recent views on violence emphasize the decline in proportions of war groups and casualties to populations over time and conclude that past small-scale societies were more violent than contemporary states. In this paper, we argue that these trends are better explained through scaling relationships between population and war group size and between war group size and conflict casualties. We test these relationships and develop measures of conflict investment and lethality that are applicable to societies across space and time. When scaling is accounted for, we find no difference in conflict investment or lethality between small-scale and state societies. Given the lack of population data for past societies, we caution against using archaeological cases of episodic conflicts to measure past violence.

Abstract: The proportions of individuals involved in intergroup coalitional conflict, measured by war group size (W), conflict casualties (C), and overall group conflict deaths (G), have declined with respect to growing populations, implying that states are less violent than small-scale societies. We argue that these trends are better explained by scaling laws shared by both past and contemporary societies regardless of social organization, where group population (P) directly determines W and indirectly determines C and G. W is shown to be a power law function of P with scaling exponent X [demographic conflict investment (DCI)]. C is shown to be a power law function of W with scaling exponent Y [conflict lethality (CL)]. G is shown to be a power law function of P with scaling exponent Z [group conflict mortality (GCM)]. Results show that, while W/P and G/P decrease as expected with increasing P, C/W increases with growing W. Small-scale societies show higher but more variance in DCI and CL than contemporary states. We find no significant differences in DCI or CL between small-scale societies and contemporary states undergoing drafts or conflict, after accounting for variance and scale. We calculate relative measures of DCI and CL applicable to all societies that can be tracked over time for one or multiple actors. In light of the recent global emergence of populist, nationalist, and sectarian violence, our comparison-focused approach to DCI and CL will enable better models and analysis of the landscapes of violence in the 21st century.

Sunday, March 25, 2018

Saturday, March 24, 2018

Analytic and/vs Continental Philosophy

Gee, this explanation of the difference between "analytic" and "continental" philosophy by Gary Gutting in a New York Times "opinionator" column of 2012 is the best explanation I've ever seen for the non-specialist: https://t.co/sr4sNvXhLQ— Alan Liu (@alanyliu) March 24, 2018

The false consciousness of the elite American university(?)

A powerful, vital essay by @PatrickDeneen on the false consciousness of the elite American university: https://t.co/L6PWxcgdhJ— Alan Jacobs (@ayjay) March 24, 2018

Here's a paragraph from the essay:

Like so many similar demonstrations against inequality at elite college campuses, the protest against Murray was an echo of resistance of the ruling class to the noble lie. The ruling class denies that they really are a self-perpetuating elite that has not only inherited certain advantages but also seeks to pass them on. To mask this fact, they describe themselves as the vanguard of equality, in effect denying the very fact of their elevated status and the deleterious consequences of their perpetuation of a class divide that has left their less fortunate countrymen in a dire and perilous condition. Indeed, one is tempted to conclude that their insistent defense of equality is a way of freeing themselves from any real duties to the lower classes that are increasingly out of geographical sight and mind. Because they repudiate inequality, they need not consciously consider themselves to be a ruling class. Denying that they are deeply self-interested in maintaining their elite position, they easily assume that they believe in common kinship—so long as their position is unthreatened. The part of the “noble lie” that once would have horrified the elites—the claim of common kinship—is irrelevant; instead, they resist the inegalitarian part of the myth that would then, as now, have seemed self-evident to the elites as well as the underclass. Today’s underclass is as likely to recognize its unequal position as Plato’s. It is elites that seem most prone to the condition of “false consciousness.”

A bit later, this:

Campaigns for equality that focus on the inclusion of identity groups rather than examinations of the class divide permit an extraordinary lack of curiosity about complicity in a system that secures elite status across generations. Concern for diversity and inclusion on the basis of “ascriptive” features—race, gender, disability, or sexual orientation—allows the ruling class to overlook class while focusing on unchosen forms of identity. Diversity and inclusion fit neatly into the meritocratic structure, leaving the structure of the new aristocratic order firmly in place.This helps explain the strange and often hysterical insistence upon equality emanating from our nation’s most elite and exclusive institutions. The most absurd recent instance was Harvard University’s official effort to eliminate social clubs due to their role in “enacting forms of privilege and exclusion at odds with our deepest values,” in the words of its president. Harvard’s opposition to exclusion sits comfortably with its admissions rate of 5 percent (2,056 out of 40,000 applicants in 2017). The denial of privilege and exclusion seems to increase in proportion to an institution’s exclusivity.

Moving toward the end:

For as long as our nation has been in existence, confused and diverging streams have fed into the American creed. The first of these was political liberalism. It puts a stress upon individual rights and liberty, promising that if we commit to a common project of building a liberal society, our distinct and often irreconcilable differences will be protected. Liberalism affirms political unity as a means to securing our private differences.Christianity has been the other stream. It approaches the question from the opposite perspective, understanding our differences to serve a deeper unity. This is the resounding message of St. Paul in chapters 12–13 of 1 Corinthians. There, Paul calls upon the squabbling Christians of Corinth to understand that their gifts are not for the glory of any particular person or class of people, but for the body as a whole. John Winthrop echoed this teaching in his seldom-read, oft-misquoted sermon aboard the Arbella, “A Model of Christian Charity.” Winthrop begins his speech with the observation that people have in all times and places been born or placed into low and high stations; the poor are always with us, as Christ observed. But this differentiation was not permitted and ordained for the purpose of the degradation of the former and glory of the latter, but for the greater glory of God, that all might know that they have need of each other and a responsibility to share particular gifts for the sake of the common. Differences of talent and circumstance exist to promote a deeper unity.So long as liberalism was not fully itself—so long as liberalism was corrected and even governed by Christianity—a working social contract was possible. For Christianity, difference is ordered toward unity. For liberalism, unity is valued insofar as it promotes difference. The American experiment blended and confused these two understandings, but just enough to make it a going concern. The balance was always imperfect, leaving out too many, always unstably oscillating between quasi-theological evocation of unity and deracinated individualism. But it seemed viable for nearly 250 years. The recent steep decline of religious faith and Christian moral norms is regarded by many as marking the triumph of liberalism, and so, in a sense, it is. Today our unity is understood almost entirely in the light of our differences. We come together—to celebrate diversity. And today, the celebration of diversity ends up serving as a mask for power and inequality.

Friday, March 23, 2018

Enlightenment how? Pinker on progress: Impressive evidence, not so impressive argument why

Nick Spencer reviews Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (Viking 2018).

... Pinker presents graphs on life expectancy, child mortality, maternal mortality, infectious diseases, calorie intake, food availability, wealth, poverty, extreme poverty, deforestation, oil spills, protected areas, war, violence, homicides, battle deaths, famine deaths, pedestrian deaths, plane crash deaths, occupational accident deaths, natural disaster deaths, deaths by lightning, human rights, state executions, racism, sexism, homophobia, hate crimes, violence against women, liberal values, child labour, literacy, education, IQ, hours worked, years in retirement, utilities and homework, the price of light, disposable spending, leisure time, travel, tourism… and much else besides.All of these, he shows, are travelling in the right direction. It’s an impressive and invigorating story...Is he convincing? For the most part: yes, very. His charts are as persuasive as they are fascinating and should make even the most ardent “progressophobe” think again. Life really is better today for most people than it has been in the past, and not just when their teeth ache. Pinker admits that “any dataset is an imperfect reflection of reality” and one can’t help but wondering how solid some of the more historical data are, but no amount of footnoted data points would change his overall argument, or even do much to dent its strength.

But Spencer has doubts about Pinker's account of this, the Englightenment, for one thing:

The Enlightenment wasn’t one single thing, or even one clearly delimited period, and its thinkers did not all want the same thing, in the same way, for the same reasons. Moreover, Pinker’s vagueness about the Enlightenment is not simply a cause of his brevity. He is also ahistorical and at times verges on caricature.The brainchildren of the Enlightenment, we are told, included “free speech, nonviolence, cooperation, cosmopolitanism, human rights, and an acknowledgement of human fallibility, and among [its] institutions are science, education, media, democratic government”. Peace was “another Enlightenment ideal”. So was “mutually beneficial co–operation [and] voluntary exchange”. “The institutions of modernity” include “schools, hospitals, charities [and] international organisations”. The Enlightenment “imagined humanity could makes intellectual and moral progress”.The idea that human co–operation, natural rights, or international peace were undreamt of before 1750 is not tenable. Schools, hospitals and charities are hardly “institutions of modernity”.

Racism, for example:

Lest we forget, the late 18th century was the time par excellence for slave trading, a commerce that was finally abolished due to the efforts of Quakers and Evangelicals rather more than Enlightenment philosophes and deists. Pinker rightly cavils at the idea that 19th century science was intrinsically racist, or that it wasn’t coloured by the racist cultures of the time. But 19th century science did not dismantle the racist cultures in which it found itself, and sometimes spent considerable time and energy fortifying them. There was such a thing as “scientific racism” and plenty of ‘enlightened’ people believed in it. Overall, it is hard to disagree with John Gray’s judgement of a previous Pinker book, to the effect that “Pinker’s response when confronted with such evidence is to define the dark side of the Enlightenment out of existence. How could a philosophy of reason and toleration be implicated in mass murder?”

Moreover (after a bit of argumentation):

In short, Pinker’s progress ex nihilo from the Enlightenment doesn’t add up. Had he been more attentive to the historical peculiarities and details of what happened in England in 1688, the rest of Europe after it, and the rest of the world after that, he might have seen the 18th century as the period not of a new and unprecedented start, but one in which Enlightenment philosophers, politicians, investors, and inventors picked up and built on the existing institutions of European order, which had been slowly crafted over centuries.

What about Christianity?

Like it or not – and Pinker clearly doesn’t – many of those cultural conditions were Christian in formulation, as the list above will have indicated. To forestall the inevitable objection, this is not to claim all the glories of the Enlightenment for Christianity. Just as the Enlightenment gave us the calculated ‘treatment’ of workhouses alongside greater political accountability, so Christianity gave us Crusades, Inquisition, and Wars of Religion, alongside the rule of law, the invention of the individual (to use Siedentop’s title) and the notion of ineradicable human dignity and equality. History is messy and no one’s biddable slave.The problem is, from reading Pinker’s book you would imagine that Christianity’s legacy to the world comprised only the former. Just as he is wilfully blind about the Enlightenment’s failings, he is wilfully blind about Christianity’s positive contribution. Most of his references to Christianity, Bible and Church are casual, sometimes snide, asides usually, indeed, about the Crusades, the Inquisition or the Wars of Religion. When he does engage with the topic, it is disappointingly thin or a little disingenuous.

Spencer's conclusion:

The final result, therefore, is a book whose punctilious, readable and important attention to detail and data in one regard (progress) is marred by its casual, vague and sometimes lazy inattention in another.What Pinker says deserves to be heard and Enlightenment Now, in spite of its historical and philosophical weaknesses, merits a wide audience. Sadly, I am not convinced that being better informed about how rich, comfortable, clever and safe we are compared to our grandparents’ generation will make us happier and more grateful (Pinker is alert to the data on unhappiness and ingratitude and discusses them at length). Nor am I as sanguine as him that all this progress has improved the quality of our relationships.However, Pinker does show that there is far more room for hope than we have in our current culture, and his take on some of the big issues that vex us, like terrorism, bio–hazards, AI, Armageddon, nuclear war, and other existential threats is a model of common sense, without slipping into complacency. Enlightenment Now deserves to be read and appreciated, but more for what it says about our future than what it does about our past.

Visual word form - "written words invaded a sector of visual cortex that was initially weakly specialized, slightly responsive to pictures of tools, and that lay next to a face-selective region"

Dehaene-Lambertz G, Monzalvo K, Dehaene S (2018) The emergence of the visual word form: Longitudinal evolution of category-specific ventral visual areas during reading acquisition. PLoS Biol 16(3): e2004103. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2004103

Abstract

How does education affect cortical organization? All literate adults possess a region specialized for letter strings, the visual word form area (VWFA), within the mosaic of ventral regions involved in processing other visual categories such as objects, places, faces, or body parts. Therefore, the acquisition of literacy may induce a reorientation of cortical maps towards letters at the expense of other categories such as faces. To test this cortical recycling hypothesis, we studied how the visual cortex of individual children changes during the first months of reading acquisition. Ten 6-year-old children were scanned longitudinally 6 or 7 times with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) before and throughout the first year of school. Subjects were exposed to a variety of pictures (words, numbers, tools, houses, faces, and bodies) while performing an unrelated target-detection task. Behavioral assessment indicated a sharp rise in grapheme–phoneme knowledge and reading speed in the first trimester of school. Concurrently, voxels specific to written words and digits emerged at the VWFA location. The responses to other categories remained largely stable, although right-hemispheric face-related activity increased in proportion to reading scores. Retrospective examination of the VWFA voxels prior to reading acquisition showed that reading encroaches on voxels that are initially weakly specialized for tools and close to but distinct from those responsive to faces. Remarkably, those voxels appear to keep their initial category selectivity while acquiring an additional and stronger responsivity to words. We propose a revised model of the neuronal recycling process in which new visual categories invade weakly specified cortex while leaving previously stabilized cortical responses unchanged.

Author summary

Reading acquisition is a major landmark in child development. We examined how it changes the child’s brain. Ten young children were scanned repeatedly, once every 2 months, before, during, and after their first year of school. In the scanner, they watched images of faces, tools, bodies, houses, numbers, and letters while searching for a picture of “Waldo.” As soon as they started to acquire reading skills, a specific region of the visual cortex of the left hemisphere—called the visual word form area (VWFA)—started to selectively respond to written words. In every child, it was then possible to go backward in time and ask what this region was doing prior to reading. We found that written words invaded a sector of visual cortex that was initially weakly specialized, slightly responsive to pictures of tools, and that lay next to a face-selective region. Reading acquisition did not displace those initial responses but blocked their development, such that face-selective responses became stronger in the right hemisphere. Those results provide direct evidence for how education recycles the human brain by repurposing some visual regions towards the shapes of letters.

Tuesday, March 20, 2018

Talk to the Wood: Animism is Natural

I'm bumping this 2011 post to the top of the queue.

But, it’s 2011 and we’re slipping rapidly past post-modernity in a world that’s in the early phases of a global ecotastrophy. Perhaps going nuts with deliberation is a prudent move. It’s good for the circulation.

Whatever.

In Beethoven’s Anvil I’ve argued that primitive proto-music created a new arena for human sociality. At the beginning of “Chapter IX, Musicking the World”, I suggest that animism is what happens when non-humans are assimilated into this new social space. It is their spirits that anchor them in this new community. Here’s that passage (pp. 195-198).

* * * * *

According to Fannie Berry, an ex-slave, Virginia slaves in the late 1850s would sing the following song as they felled pine trees:

A col' frosty mo'nin'

De niggers feelin' good

Take you ax upon yo' shoulder

Nigger, talk to de wood.

She went on to report that:

Dey be paired up to a tree, an’ dey mark de blows by de song. Fus’ one chop, den his partner, an’ when dey sing TALK dey all chop togedder; an’ purty soon dey git de tree ready for to fall an’ dey yell “Hi” an‘ de slaves all scramble out de way quick.

The song thus helped the men to pace and coordinate their efforts. Beyond that, Bruce Jackson notes of such songs, “the songs change the nature of the work by putting the work into the worker’s framework...By incorporating the work with their song, by in effect, co-opting something they are forced to do anyway, they make it theirs in a way it otherwise is not.” In the act of singing the workers linked their minds and brains into a single dynamical system, a community of sympathy. By bringing their work into that same dynamic field, they incorporate it into that form of society created through synchronization of interacting brains.

What is the tree’s role in this social process? It cannot be active: it cannot synchronize its activities with those of the wood choppers. But, I suggest, “putting the work into the worker’s framework” means assimilating the trees, and the axes as well, into social neurodynamics. The workers are not only coupled to one another; by default, that coupling extends to the rest of the world. What does it mean to treat a tree or an ax as a social being? It means, I suggest, that you treat them as animate and hence must pay proper respect to their spirits.

Thus we have arrived at a conception of animism, perhaps mankind’s simplest and most basic form of religious belief. In this view animistic belief is a natural consequence of coupled sociality. In effect, the non-human world enters human society as spirits and, consequently, humans perform rituals to honor the spirits of the animals they eat, or the trees they carve into drums, and so forth. With that in mind let’s consider a passage from Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines, an intellectual and spiritual journey into Australia’s Aboriginal outback. In this passage Chatwin is talking with Arkady Volchok, an Australian of Russian descent who was mapping Aboriginal sacred sites for the railroad. Much of the outback is relatively featureless dessert, and navigation is a problem if you don’t have maps and instruments, which, of course, didn’t exist until relatively recently. The Aborigines used song to measure and map the land:

[Arkady] went on to explain how each totemic ancestor, while traveling through the country, was thought to have scattered a trail of words and musical notes along the line of his footprints ... as ‘ways’ of communication between the most far-flung tribes.

‘A song’, he said, ‘was both map and direction-finder. Providing you knew the song, you could always find your way across country.’

‘And would a man on “Walkabout” always be travelling down one of the Songlines?”

‘In the old days, yes,’ he agreed. ‘Nowadays, they go by train or car.’

‘Suppose the man strayed from his Songline?’

‘He was trespassing. He might get speared for it.’

‘But as long as he stuck to the track, he’d always find people who ... were, in fact, his brothers?’

‘Yes.’

. . . .

In theory, at least, the whole of Australia could be read as a musical score. There was hardly a rock or creek in the country that could not or had not been sung. One should perhaps visualise the Songlines as a spaghetti of Iliads and Odysseys, writhing this way and that, in which every ‘episode’ was readable in terms of geology.

. . . .

‘Put it this way,’ he said. ‘Anywhere in the bush you can point to some feature of the landscape and ask the Aboriginal with you, “What’s the story there?” or “Who’s that?” The chances are he’ll answer “Kangaroo” or “Budgerigar” or “Jew Lizard”, depending on which Ancestor walked that way.”

‘And the distance between two such sites can be measured as a stretch of song?’

We are now prepared to answer that question in the affirmative, as Arkady Volchok did. Given the nature of navigation by dead reckoning—that it requires accurate estimates of elapsed time—and the temporal precision of musical performance, it makes sense that one would use song to measure one’s path in a desert with few discernible features. Given our further speculation that music’s narrative stream is regulated by the brain’s navigation equipment, this Aboriginal Song-as-Map seems like a natural development.

Nabakov's "Lolita" and an example of ethical criticism

I recently came across an essay by Michael Doliner, Advanced Creepology: Re-Reading “Lolita” (Counterpunch). It struck me as being a very good piece of literary criticism, and that's why I'm mentioning it here, as an example of good, if 'conventional' literary criticism. I should note that I've not read the book in decades, so perhaps it's not as good as I think it is. Still, I present it as a good way of writing about literature. Here's an example passage:

Lolita’s twelve-year-old body with it’s twelve-year-old nature reveal her as a nymphet, but Humbert remains in love with her long after it is gone. When he finds her again at the squalid home of Mr. Richard F. Schiller, he continues to love, without wavering, the woman she has become. Whatever else Humbert is, he passes Shakespeare’s test of love, namely, that love is not love that alters when it alteration finds. And since Humbert loves nymphets, she must still be a nymphet, for she is still Lolita. Humbert offers to take her away and live with her forever. Dolores declines the offer.… and there she was with her ruined looks and her adult, rope-veined narrow hands and her goose-flesh white arms, and her shallow ears, and her unkempt armpits, there she was (my Lolita!), hopelessly worn at seventeen, with that baby, dreaming already in her of becoming a big shot and retiring around 2020 A.D. — and I looked and looked at her, and knew as clearly as I know I am to die, that I loved her more than anything I had ever seen or imagined on earth, or hoped for anywhere else.Just as the nymphet need not be conventionally beautiful, she also need not be prepubescent.He sells everything and gives her the money. His days of being transfixed by nymphets are over. He still looks at them, but there is no Erotic connection. Lolita is his one and only love. He heads out to kill Quilty. She, that is Mrs. Richard Schiller, goes to Alaska to die in childbirth.Nabokov had tried to write Lolita several times while still in Europe. What he had been missing came to him suddenly soon after he came to America, and he wrote the novel while he and his wife Vera were on a butterfly hunting trip. To write the whole novel while spending days out chasing butterflies and driving from place to place makes it sound like the novel must have come to him in a rush. Nabokov could write Lolita soon after coming to the United States because Lolita had to be an American girl, and Humbert had to come to America. Nabokov needed Lolita to have an innocence contending with vulgarity that he discovered here. Humbert needed to be a European discovering this in America. Europe, after the second world war, is too exhausted, too jaded, too sophisticated to support a Lolita.Lolita, a spirit who inhabits Dolores, is visible only to one who can see her lace-like existence, one led by Eros, a desire for possession of the beautiful. But when the opportunity comes, Humbert defiles her with her willing collaboration. Until the fateful moment Humbert had been more than satisfied with possession of his furtive experiences. Humbert’s physical possession of Lolita destroys her and leaves Dolores with a deep indifference. As with butterflies that Nabokov killed so as to possess their beauty, Humbert killed Lolita spiritually when he possesses her. Lolita’s existence and her destruction have the same cause, Eros unrestrained by a sufficient respect for the divine.However, it is Lolita who initiates the actual sex with Humbert. Before that her proximity was all he dared to hope for. It was more than enough to sense the vibrations on the strands of his web. His timidity was paralyzing. To be sure she had been seductive, but it had been playful. He would not have dared to violate her. Humbert describes Lolita’s initiation of him into sex as, for her, no big deal. The head-counselor’s son had already deflowered her in camp and she thought of sex as another camp activity. It was just a thing, like tennis or canoeing. The refined Humbert sees Lolita’s diaphanous charm within her undeniable vulgarity revealed in a matter-of-fact attitude to this monstrous sin.

As you can see from this passage, this is not academic literary criticism, it does not employ any of the various critical theories and methodologies that have proliferated in the last half century. And yet it is certainly intellectually sophisticated. One could imagine such ideas being developed via one or more or these methodologies.

I present this as an example of what, following the late Wayne Booth, I have come to call ethical criticism, as opposed to the naturalist criticism for which I have been arguing. What place does it have in the university? That's what I want someone to tell me. Surely it has a place, certainly in the undergraduate curriculum. The sorts of things discussed in this essay are what brings one to literature, what one seeks to clarify through literature. No?

Yes.

Saturday, March 17, 2018

The discipline of literary criticism and the difference between graduate and undergraduate education

Michael Meranze reviews a new book by Geoffrey Harpham, What Do You Think, Mr. Ramirez?: The American Revolution in Education, which centers on the definition and role of the humanities, literary criticism in particular. After a bit of introductory material we have this paragraph:

Harvard University’s General Education in a Free Society offered the crucial conceptualization of the humanities within general and liberal education. Commonly known as the “Redbook” (for the color of its cover), General Education in a Free Society was a protean text. Its greatest influence appears to have been in promoting lower-division general education in colleges and universities, though its notion of the centrality of general education was far too capacious for postwar academic institutions. Arguably, the Redbook was the last attempt to define higher education as a humanist enterprise that was not a defensive gesture: its authors — a Committee empaneled by Harvard President James Bryant Conant — asserted that the humanities and social sciences lay at the core of higher education. The aim of education was the instillation of “wisdom,” conceived as an “art of life,” a cultivation of the “whole man.” None of these lofty terms would survive the intellectual challenges of the next half-century. But they proved to be powerful arguments in the midcentury debate over the creation of a mass higher education system in the United States.

And then, and then, until:

As Harpham shows, the New Criticism was as much a pedagogy as a research program. Late 19th- and early 20th-century English studies was divided, to use Gerald Graff’s terms, between scholars and generalists. Scholars based their authority on a Germanic tradition of philological rigor while generalists, believing this approach missed the element of genius in literature, embraced the theater of charismatic teaching. Ultimately this divide was settled in practice through the separation of graduate training from an undergraduate curriculum of appreciation. This arrangement allowed both sides to participate in a larger project of “criticism” that would, on the one hand, establish the professional status of literary critics while, on the other hand, maintaining the undergraduate enrollments that kept professors employed.The New Criticism provided the means to bring these two visions together into one pedagogical program. As envisioned by I. A. Richards and elaborated by William Empson, the New Criticism’s emphasis on close reading and the structures of language allowed professors simultaneously to claim a new, more scientific method and to dazzle undergraduates with interpretive possibilities. Moreover, because the New Criticism opened up a seemingly endless debate about authorial intention, it made literary criticism into a powerful tool for tackling the interpretive dilemmas of American civic culture. New Criticism, in short, transformed constitutional interpretation into literary interpretation and therefore opened up the possibility of training students to read the texts of America in a more critical fashion.

And that's what interests me, the distinction between undergraduate education and graduate training. It has long seemed to me that what's most important about (lower-division) undergraduate courses in literature is the texts themselves. It almost doesn't matter what we say around and about them as long as students are taught/allowed to take them seriously (whatever that may mean). Graduate training and professional research, however, may be somewhat different in character–a matter I discuss at greater length in a working paper, An Open Letter to Dan Everett about Literary Criticism. Here's the abstract:

Literary critics are interested in meaning (interpretation) but when linguists, such as Haj Ross, look at literature, they’re interested in structure and mechanism (poetics). Shakespeare presents a particular problem because his plays exist in several versions, with Hamlet as an extreme case (3 somewhat different versions). The critic doesn’t know where to look for the “true” meaning. Where linguists to concern themselves with such things (which they mostly don’t), they’d be happy to deal with each of version separately. Undergraduate instruction in literature is properly concerned with meaning. Conrad’s Heart of Darkness has become a staple because of its focus on race and colonialism, which was critiqued by Chinua Achebe in 1975 and the ensuing controversy and illustrates the problematic nature of meaning. And yet, when examined at arm’s length, the text exhibits symmetrical patterning (ring composition) and fractal patterning. Such duality, if you will, calls for two complementary critical approaches. Ethical criticism addresses meaning (interpretation) and naturalist criticism addresses structure and mechanism (poetics).

Friday, March 16, 2018

Wednesday, March 14, 2018

5003

This is to say, this is my 5003rd post here at New Savanna. I reached 2500 on July 14, 2014, and did a not so long post where I took a quick look at what I've been up to here. Should I take another wack at it? That stuff seems both so recent and so long ago. In lieu of doing a post where I attempt to characterize what's happened in the three-and-a-half years since then I'll just like to a post I did in the middle of December:

Reflections on entering my eighth decade and why it portends to be the most productive one of my life

For what it's worth, that post projects an optimism that I'm not feeling at the moment, but who knows what the morrow will bring?

Trump in Korea, and some more personal reflections

There’s no doubt about it, North Korea has been a knotty challenge for American foreign policy, not–mind you–that I’m a fan of that foreign policy, which has long seemed, shall we say, excessively bellicose. Until quite recently President Trump simply amped up the aggression and seemed entirely too sanguine about the prospect of war with North Korea. Then, all of a sudden, Trump tells us that he’s accepted an overture from Kim Jong-un to talk about Korea’s nukes.

What? Just like that! That’s a good thing, no?

That’s what I felt for maybe a day. And then I began reading commentary by those more deeply informed in such matters than I am. These worthies were not at all encouraging. Quite the contrary, they’ve been rather discouraging and disparaging.

Forget about Trump’s many personal flaws – lack of impulse control, narcissism, megalomania, etc. (Not to mention his misogyny, though that doesn’t seem directly relevant in this matter.) It’s not that these aren’t issues, they are; but let’s just set them aside. Rather, this just isn’t how these things are done. The right way to do this is to have underlings and deputies hash things out for months and even years, ironing out all the kinks, and only then bring in Trump and Kim at the very end. They do a bit of sniffing about, find that it’s all good, and sign on the dotted lines their deputies have drawn. Very cautious, very deliberate.

Besides, for Trump to agree to talks with Kim is to give away half the game, or more, at the very start. Regardless of what the talks produce, if they produce anything at all, Kim wins prestige and legitimization points both at home and abroad. But is that so bad? Who knows, maybe that would settle him down. And maybe not.

But the fact is, business as usual – which is what the worthies want – hasn’t been working all that well, has it?

* * * * *

Meanwhile, I’ve had one of those moments I seem to have been having every few weeks or months. It’s generally during the night when I’m neither fully awake or fully asleep. They don’t last long, a matter of minutes at most. And they’re difficult to characterize.

It’s as though my mind were trying to detach itself from my person and become Mind Itself and thereby grasp the World Whole, if that makes any sense. On the one hand the world is what it is and cannot be escaped. It is utterly necessary. And at the same time seems utterly contingent, as though it could easily have been otherwise. All we need is for that butterfly over China to flutter its wings and history is changed. But what if it’s nothing but butterflies all the way down?

There’s so much human diversity in the world, so many different ways of life, so many different individual life histories. Taken individually, one at a time, each in its socio-historical context, they seem fixed and determinate. But when you consider the differences, each seems utterly contingent and arbitrary.

What if we could circulate minds freely from one to another?

* * * * *

Does The Donald have such moments? What I’ve just said seems rather too abstract and too intellectual for him. If he has such moments, they wouldn’t manifest in such terms. The terms would be different.

Is that what was going on in his insistence that more people attended his inaugural day than any other? In his absurd insistence that the photographs of people on the Mall were FAKE NEWS? Sure, his narcissism, his need to assert his power by forcing his deputies to participate in his delusion. All that.

But beneath it all, was he attempting to find a bit of freedom?

Count me among those who believes he didn’t really want to win–noting that there are various ways one can interpret that. But he won and now THUD! he’s stuck with the job. He’s trapped–in the White House, with all these obscure and difficult responsibilities. His world is changed, utterly.

What’s he think he can do sitting across a table from Kim Jong-un? Two men, with nuclear arms between them, and the world on their shoulders. Is that how they wrestle with the Real?

* * * * *

If I were a religious man I’d be praying for them to find peace in a handclasp.

Tuesday, March 13, 2018

Paths Not Taken and the Land Before Us: An Open Letter to J. Hillis Miller

From three years ago (Jan 2015).

I’ve been thinking about writing a guide to my work in literary and cultural criticism, but there’s so much of it that that has seemed to be no simple task. I could list the pieces, but what use is that? And in any event, you can find that on my most recent CV. But I’ve decided to take a step in that direction by addressing an open letter to one of my teachers back at Johns Hopkins, J. Hillis Miller.

That gives me a fairly specific audience. It’s much easier to address a specific audience, with known interests, than to address the General and Undefined Other. I certainly don’t know Miller’s criticism in any detail, but I’ve read several recent pieces and interviews where he talks about the profession in general historical terms. That, plus resonance from ancient days at Hopkins, is enough for me.

For those of you in literary studies, J. Hillis Miller needs no introduction. He is one of the premier English language critics of the last half-century. For those in other disciplines, Miller’s career started at a time when interpreting texts was just becoming accepted in academic literary criticism and he became central in the use of philosophy, broadly understood, in that undertaking.

* * * * *

Dear Prof. Miller:

I’ve been mulling over the wonderful profile of Earl Wasserman that was recently published in the Hopkins Magazine. That got me thinking about the state of the profession, the transit from then to now, and where are we going anyhow? Wasserman, of course, was your colleague and he was my teacher. As it was the "structuralist moment" that ultimately captured my imagination, Wasserman was not so central as Dick Macksey, but he was still very important to me, in part through the exemplary force of his intellectual engagement. I also audited one of your graduate courses (as I recall, Carol Jacobs was a student in that course). I believe you even wrote a graduate school recommendation for me.

The profession used the structuralist moment to go in one direction and I used it to go in a rather different one. On the chance that you might be curious about where I’ve ended up I thought I would write you a letter. FWIW (an abbreviation for a phrase that titled one of the great protest songs of the 60s, “For What It’s Worth”) the open letter is a form I find congenial, having addressed letters to Steven Pinker, Alan Liu, and Willard McCarty.

A Fork in the Road

For the profession the structuralist moment rather quickly gave way to deconstruction, post-structuralism, cultural studies, and various identity-based criticisms, all of which somehow became snarled in a ball that became “Theory.” For me, however, structuralism gave way to cognitive science and that’s what I grafted to literary study at SUNY Buffalo. That English department was as wondrous in its own way as the Hopkins department was in a somewhat different way. One of the small wonders is that it granted me a degree despite the fact that no one in the department was deeply involved with cognitive science (I got that in the Linguistics Department, from a polymath named David Hays).

The profession, alas, was not ready for cognitive science at that time. By the time the profession began coming around to it in the mid-1990s I had come to believe that I had misjudged the significance of cognitive science. As important and interesting as those theories and models were (and still are) I decided that cognitive science had a different message, one that echoes an older one, a Wassermanian message: stick to the text.

It was the text of “Kubla Khan” that sent me to cognitive science in the first place and now cognitive science has sent me back, not simply to “Kubla Khan,” but to any and all texts. They all need to be looked at closely, not necessarily in a New Critical or a phenomenological, or a narratological, or a deconstructive way, but closely, more closely than ever before. I’m told that the kids these days call it surface reading.

Though I’ve been publishing in the formal literature off and on, perhaps your best route into what I’ve discovered would be through a series of informal working papers I’ve recently put online. I’ve spent quite a bit of time blogging over the past several years and, in particular, have specialized in “long-form” posts, posts running 2000 words or more. When I’ve accumulated a set of such posts on one topic I combine them into a single document and then make it available online for downloading.

Such working papers are more coherent than private notes, but not so polished as formal papers. The scholarly apparatus–references, discussions of other work–is a bit thin. And they’re a bit repetitious, for which I will not apologize as skipping over things is easy enough to do.

I’ve selected five working papers:

- Heart of Darkness: Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis on Several Scales (2011, 48 pp.): https://www.academia.edu/8132174/Heart_of_Darkness_Qualitative_and_Quantitative_Analysis_on_Several_Scales

- Apocalypse Now: Working Papers (2011, 51 pp.): https://www.academia.edu/7866632/Myth_From_Lévi-Strauss_and_Douglas_to_Conrad_and_Coppola

- Myth: From Lévi-Strauss and Douglas to Conrad and Coppola (2013, 12 pp.): https://www.academia.edu/7866632/Myth_From_Lévi-Strauss_and_Douglas_to_Conrad_and_Coppola

- Ring Composition: Some Notes on a Particular Literary Morphology (2014, 59 pp): https://www.academia.edu/8529105/Ring_Composition_Some_Notes_on_a_Particular_Literary_Morphology

- Reading Macroanalysis: Notes on the Evolution of Nineteenth Century Anglo-American Literary Culture (2014, 100 pp.): https://www.academia.edu/8183111/Reading_Macroanalysis_Notes_on_the_Evolution_of_Nineteenth_Century_Anglo-American_Literary_Culture

You are of course free to examine them in any order, but there is a reason for that particular order. I start with a set of posts on important text that I know you have written about, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Apocalypse Now is a rather different text in a different medium, but nonetheless intimately related with Heart of Darkness as Coppola kept a copy of Heart with him while shooting his film. Those two working papers each in its way harkens back to my structuralist roots, which come to the fore in the next two working papers. The fourth one (on ring composition) also discusses some poems: Dylan Thomas, “Author’s Prologue”, Coleridge, “Kubla Khan”, and Williams, “To a Solitary Disciple”.

The last working paper, and the longest by far, heads out into conceptual territory which I assume, perhaps mistakenly so, will be strange to you, the “distant reading” division of the so-called digital humanities. One of the things I do in that paper, however, is use Matthew Jockers’ large-scale analysis of a corpus of 3300 19th century English-language novels to make a case for the autonomy of the aesthetic realm. That is to say, I use (someone else’s) computational analysis to make a case for human freedom.

I don’t know what your thoughts are on the use of computers in literary study, but I do know that there are many who believe that they are a harbinger of the Apocalypse, which is what an earlier generation of critics thought about deconstruction and the rest. The sky didn’t fall then and it’s not falling now. But there are accommodations to be made, and they are not always easily accomplished.

Heart of Darkness

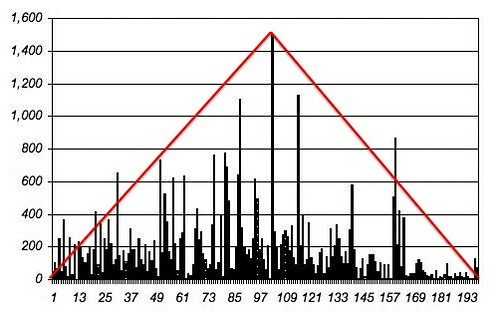

In some of your remarks about your career you talk about the importance of accidents. Well, I decided to read Heart of Darkness as a consequence of having immersed myself in Apocalypse Now, which we’ll get to in a bit. Once I’d been working on Heart of Darkness for a while I more or less stumbled into making this chart:

Each bar in the chart represents one paragraph in the text (the electronic version available from Project Gutenberg). The bars take the paragraphs in order from first to last, left to right. The length of a bar is proportional to the length of a paragraph. While the lengths vary wildly, there seems to be a shape to the distribution, which I’ve indicated by those red lines.

Is that shape real? If so, what is its significance and how did it come about? Did Conrad intend the text to be that way? Old questions, no?

I didn’t arrive at those questions and that chart through any prior interest in paragraph length. I got there because I’d become interested in one extraordinary paragraph. Until this particular paragraph Kurtz was little more than an enigma attached to a name. This paragraph gives us his history and some of his thoughts about the future. But that’s not what attracted me to it. What attracted me is that the paragraph contains proleptic elements, the only one in the text to do so. At this point in the narrative we’ve not yet arrived at Kurtz’s compound, but that paragraph contains hints of what we’re going to find there. So I was on the trail of a difference between story and plot: Russian Formalism, narratology.

Moreover, this paragraph is framed in an extraordinary way. Just before Marlow speaks this paragraph he tells us that his helmsman got speared and dropped bleeding to the deck. Just after this paragraph Marlow tells us of pushing the dead man off the deck and into the Congo. So Conrad inserts Kurtz’s story into the moments when the helmsman bleeds out on the deck.

What an extraordinary thing to do.

Well, as I was examining that paragraph, I couldn’t help but notice how very long it was. It seemed that it was the longest in the text by far. Since I had a digital text I decided, on a whim, to use MSWord’s count function to count the number words in each paragraph. It was tedious and took awhile – though not even remotely comparable to the tedium of constructing a concordance using 3 by 5 cards – but it was easy enough to do.

Once I’d done it I ran off that chart to see the results. Sure enough, that extraordinary paragraph was the longest one in the text, and by a considerable margin That’s it, at the peak of the pyramid. It was just over 1500 words long while the next two longest paragraphs weren’t even 1200 words long.

Given what’s actually said in that paragraph and its immediate context, I find it hard to believe that its length was an accident. I also find it hard to believe that Conrad was counting words. However, I have no trouble at all believing that he wanted to create some suspense by dropping the helmsman to the deck and then leaving him there while going on a grand digression. Laurence Sterne did that sort of thing some years earlier.

In that chart, it seems to me, we’re looking at the trace of a mental act, a trace we don’t know how to explain. It’s also a trace we don’t know how to convert into meaning through any of the usual conceptual tools. Maybe we need some new tools? Perhaps a different set of questions?

FWIW, I reported that chart to Mark Liberman at Language Log, a group log of linguists, because I wanted to see if linguists had done any work on paragraph length. He went to work on Nostromo and The Golden Bowl, a rather different text by one of Conrad's contemporaries, and reported the results in a post, Markov's Heart of Darkness. This occasioned a fair bit of discussion about paragraphing. I found it interesting and concluded, provisionally, that no one knew much about paragraphing.

In one section of that working paper I write a commentary on that paragraph. I quote the paragraph in full and insert observations into the text. I’m not looking for anything deep in those observations. I just note what’s there and establish links to other parts of the text.

Marlow’s tale of his trip up the Congo is, of course, embedded in a frame tale, set on the deck of a yacht in the Thames. If we think of that one very long and very strongly marked paragraph as a tale within the tale, that gives us a tale (Kurtz’s history in that paragraph), within a tale (Marlow’s trip), within a tale (the frame story). On that basis I argue that Heart of Darkness exhibits a loose version of ring-form composition, a topic that made its way into PMLA in 1976, where I noted it and set it aside, and that occupied the late Mary Douglas during the last decade or so of her career. I’d begun corresponding with her after she’d blurbed my book on music (Beethoven’s Anvil) and she asked me whether I had any idea of how the brain would do that. That set me on the trail of ring-composition, but I’ll get to that later.

There’s a good deal more in that working paper–a bit of Latour, some attachment theory (which I learned from Mary Ainsworth at Hopkins), a discussion of Achebe in relation to Ike Turner and Sam Phillips, psychohistory, and whatever else–but I won’t try to summarize it here. Let’s just say it’s an eclectic mix and leave it at that.

Monday, March 12, 2018

Do Literary Texts Count as Strong Evidence about the Human Mind?

Once again, I'm reposting this. My concern, as before, is with taking literary texts seriously, as primary evidence. Just how do we do that? It seems to me that interpretive approaches, by directing our attention to "hidden" meaning, allow the text itself to be explained away. At the moment I'm interested in ring form, and I don't want that ring form explained away. It's doing work: what work? It's primary evidence about how the human mind works. We must understand it, not explain it away.

Given my recent comments on description and the teleome, where I argue that a robust descriptive understanding of the arts is our best source of clues about how the full range of neural systems operates in the course of living a life (Deep Learning, the Teleome, and Description, Description and the Teleome, Part 2), this old post from The Valve deserves a re-post. I originally posted in on December 14, 2009.

* * * * *

Given my recent comments on description and the teleome, where I argue that a robust descriptive understanding of the arts is our best source of clues about how the full range of neural systems operates in the course of living a life (Deep Learning, the Teleome, and Description, Description and the Teleome, Part 2), this old post from The Valve deserves a re-post. I originally posted in on December 14, 2009.

Let me repeat my favoriate analogy about the relationship between biology and culture in human life, that of a board game such as chess. Biology provides the game board, the pieces, and the basic rules. Culture provides the strategies and tactics used in joining elementrary moves into viable games play. Literary texts are then records of strategy and tactics in action. The first job of criticism, then, is simply to describe the game as it happened. Interpreting the intentions animating strategies and tactics is secondary and utterly dependent on accurate description.

* * * * *

Now that Bérubé’s review of Boyd has got me thinking about “Darwinian criticism” or “evocriticism,” I want to look at a passage in Boyd’s book that is, in effect, the generalization of his criticism of the notion that romantic love is culturally specific. Here it is (Brian Boyd, The Origin of Stories, Harvard 2009, p. 385):

Evocriticism can offer a literary theory both theoretical and empirical, proposing hypotheses against the full range of what we know of human and other behavior, and testing them. Though compatible with much earlier theory and criticism [that is to say, before “Theory” and its immediate precursors], it will reject some possibilities, such as assumptions of radical disjunction between human minds of different eras or cultures based on a general cultural constructivism or particular “epistemic shifts.”

It may be the case these days that “radical disjunction” between different eras and cultures is simply assumed, but there was a time when the disjunction was argued on the basis of evidence and, as far as I know, people are still making such arguments and presenting evidence in their favor. Isn’t that what historicist criticism is about? That is to say, Boyd seems to be implying that people just made up stuff about disjunction because they felt like it but that they didn’t have an plausible reason. He’s wrong on that, no?

And the reasons that have been and still are given involve both literary texts and non-literary texts. You read texts of different eras and cultures, you read them closely, and come to the conclusion that they thought and felt about X Y & Z differently than we do know or than those folks over that at that time. Hence there is a disjunction between our mind, their mind, and theirs as well. (I’ll dispense with “radical” as it seems to me to function as something of a weasel word in this general context. Just how much of a disjunction qualifies as radical?)

What I want to know is whether or not these various texts count as primary evidence, evidence that can’t be interpreted away? In particular, is it valid always to subordinate the evidence of those texts to the evidence of evolutionary psychology?

Sunday, March 11, 2018

A quick take on civilization by Nina Paley

Civilization: pic.twitter.com/oj7Qd8EkDA— Nina Paley (@ninapaley) March 11, 2018

Time's Arrow in Literary Space: Irreversibility on Three Scales

Another bump to the top. A topic I still think about.

* * * * *

Here's a not-so-old post from The Valve (March 2010) on a topic that fascinates me. I first published it on New Savanna on June 6, 2011. I'm bumping it to the top of the pile because it resonates with my recent work on Matt Jockers' Macroanalysis. Jockers found a century-long pattern (one scale) in a large corpus of texts that just happens to be temporal, but wasn't defined in temporal terms. This post takes up the topic of literary temporality on two other scales: years (Osamu Tezuka) and decades (William Shakespeare). If this post interests you, you might want to go over to The Valve and read the discussion there, which is quite interesting.

Is literary time directional? In some sense the answer, obviously, is “yes.” There is no doubt that Pride and Prejudice was written before A Passage to India. The issue, however, is whether or not Pride and Prejudice must have been necessarily, in some sense, before A Passage to India and, if so, in what sense it must have been written first.

Stephen Greenblatt comes close to suggesting what I’m up to early in “The Cultivation of Anxiety: King Lear and His Heirs” (Learning to Curse, Routledge, 1990, pp. 80—98) which opens with a long passage from an early 19th century magazine article on the how the Reverend Francis Wayland broke the will of his 15-month old child. Greenblatt notes that “Wayland’s struggle is a strategy of intense familial love, and it is the sophisticated product of a long historical process whose roots lie at least partly in early modern England, in the England of Shakespeare’s King Lear.” To be sure, one need not read that as any more than a statement of historical contingency, that Shakespeare’s play just happened to have been written before Wayland’s article. But when one considers the larger institutional changes Greenblatt considers – from the public space of the king’s court (and Elizabethan stage) to the privacy of the bourgeois home – one may suspect that Greenblatt is tracking the directionality of literary time, that one text must necessarily have been earlier in the historical process in which both texts exist.

That directionality is what I want to look at, but not primarily on the scale of decades-to-centuries. My principle example involves three early texts by Osamu Tezuka, the great Japanese mangaka. He was born in Nov 1928, which puts him in his early 20s when these texts were written during the American occupation of Japan after World War II. The three texts have become known collectively as his SF trilogy: Lost World (1948), Metropolis (1949), and Next World (1951). Thus, they are early texts; in particular, they are before the Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy) stories that became the centerpiece of his work for almost two-decades.

Prior to World War II Japan had an unbroken history as an independent state stretching all the way back to . . . the primordial times of Japanese mythology. The Japanese Emperor was the living embodiment of that continuity and connection. When he surrendered, that continuity was cut and with it the whole mythological and ideological apparatus that gave shape to the Japanese world, it was gone. Even for someone like Tezuka, who was not a partisan of the militarist regime that ruled Japan at the time, that must have created a profound existential problem. And so, one of the things we see Tezuka doing in this three texts is re-creating a sense of Japan. He is creating a new myth. Without that, how can there be any sense of order about the cosmos?

While there is much one could say about these texts, here I wish to raise a specific issue: Is the order in which Tezuka in fact wrote those three texts the order in which he must necessarily have written them. I don’t have a strong argument to offer. Rather, I simply want to raise the issue. Lurking behind this issue is, of course, another, for if the order IS necessary, whence the necessity?

Tezuka’s Rediscovery of Japan

The first of these texts, Lost World (1948; English translation, Darkhorse Comics, 2003), is set on two planets, Earth and Mamango, a twin of Earth that comes near to Earth every 5 million years. The geographical location of the Earth-bound events is not clear; no geographic locations are named, no cities, no countries. By default, a Japanese audience would be likely to locate these events in Japan (and some of the characters have Japanese names, e.g. Shikishima). But, when the story ends, two people, a man and a woman, remain on Mamango, and will create a new race of human beings. That is to say, in this story, the exciting new stuff of the future is going to take place somewhere else than on Earth.

The second of these texts, Metropolis (1949; English translation, Darkhorse Comics, 2003), is mostly set in some large city named Metropolis, which is explicitly not-Japan. Two of the central characters, Detective Mustachio and his nephew Kenichi, however, are identified as being from Japan and thus being Japanese. Mustachio announces himself as being from Japan (p. 46, cf. p. 53). Japan is now explicitly identified in the story, it is a named place that is differentiated from other names places, such as Metropolis and Long Boot Island. But Japan is not a site of action that is significant to the story.

The last of these texts, Next World (1951; English translation, Darkhorse Comics, two volumes, 2003), is set in locations all over the world. Much of it takes place in the capitalist Nation of Star (obviously the United States) and the socialist Federation of Uran (obviously the Soviet Union). But the story begins in Japan, has episodes there, and ends in Japan. In one plotline the Earth is being threatened by a large approaching mass of space gas. Once this phenomenon is perceived and categorized as an Earth-wide threat, there is a segment where the heads of Star and Uran say, “Let’s escape to Japan” (Vol. 2, p. 99) So Japan is an explicit destination for the most powerful politicians on Earth. Japan is on the map and it is the location of events significant to the story.

It turns out that the gas cloud somehow got neutralized before it reached Earth, so everyone survived. Star and Uran had gone to war, but that was stopped by the Fumoon, advanced humanoids that seemed to have been the product of radioactive fall-out from atomic tests done by Star and Uran. (Yeah, this is a complicated mess of a story.) The point is that Tezuka has positioned Japan outside the conflict between Star and Uran. That is its position in the world and, whatever the geographical relationships between the three nations, Tezuka has given it a political role to play in this, the last of the three books in his SF trilogy. Japan now has a differentiated identity.

On this one matter, Japan as a geographical and political entity, we see a clear progression that matches the order of publication. In the first text Japan is not mentioned at all; in the second it is named, but is peripheral to the action; in the third it is named and becomes a central locus of action on the international scene. Still, the fact that Tezuka wrote the text wrote the texts in that order does not necessarily imply that he had no choice but to write them in that order. To say that he had to write them in that order is to imply some process in his mind that takes place on the scale of months to years and that is linked to his story-telling activity in such a way as the place strong restrictions on the stories he can construct in any given period.

Let’s return to my assertion–merely assumed here, without argument–that Tezuka is using these texts as a vehicle for restoring some sense of order in the world in the wake of Japan’s defeat. We know that he found that transition to be traumatic. As Frederick Schodt has noted in The Astro Boy Essays (Stonebridge Press, 2007, pp. 29-30):

With the end of the war, new difficulties appeared. Tezuka also witnessed starvation among a once proud people, and during the wild, unstructured early days of the occupation, he suffered the humiliation and anger of being beaten by a group of drunken American GIs who could not understand his broken English. It was a brutal and direct experience in cultural misunderstanding that he never forgot. Like all young Japanese of his age, he had also seen how an authoritarian government—his own—had been able to manipulate information and public opinion, and how, after the war, the entire value system of the country was overturned and replaced by a new democratic ideology. It was horrifying, he later said, to realize that “the world could turn 180 degrees, and that the government could switch the concept of reality,” so that what had been “black” or “white” only days before was suddenly reversed.

All of that, I believe, is what Tezuka was working through while writing these three stories, Lost World, Metropolis, and Next World. I suggest that the process was comparable to mourning the death, for example, of one’s parents. As such it was a process that involved his whole psyche and not just some relatively localized notions about how the state functions and just who is in office now. And it is not just that Tezuka was working through the death of his nation during this period, but that he was using his fiction as a vehicle to work through that process and so to arrive at the beginnings of a new conception of Japan, its place in the world, and the place of individual Japanese in this emerging Japan.

We are still a long way from understanding just how and why the demands of this psycho-symbolic process influenced Tezuka’s manga so as “determine” the order in which certain themes and motifs appeared in them, but that is what I think is going on. That is the direction our investigations must take if we are to gain a deeper understanding, not only of Tezuka’s artistic work, but of artistic work in general, and of the human mind.

Longer Time Scales

Tezuka wrote these three texts over a period of three to four years. What about longer time spans? Many artists have been productive over decades and it is common to talk of early, middle, and late works, not as mere temporal markers, but as indicators of characteristic themes, concerns, and sometimes even of aesthetic quality. Some of this development may reflect technical command of the medium, but surely we are dealing with personal development and maturation as well.

Shakespeare presents an interesting case. Early in his dramatic career he tended to write comedies and histories; then he gravitated to tragedy; and he finished his career with curious tragic-comic hybrids, or romances. In a paper that looks at one play from each of these periods—Much Ado About Nothing, Othello, and The Winter’s Tale—I relate this sequence to ideas about adult development by Erik Erikson, Daniel Levinson, and George Valliant. Thus, while we can read or see Shakespeare’s plays in whatever order we wish, and at whatever time in our lives we wish, Shakespeare himself was constrained to write certain kinds of plays during certain periods of his life. There was a certain necessary order to his artistic production. He could not have written Othello before he wrote Much Ado About Nothing, nor The Winter’s Tale before either of those others. His psyche made demands on his artistic work, and his artistic work was a vehicle for shaping his psyche.

But the life of literature is longer than the lives of any individual writers and readers. And so we are back at the time scale implied in Greenblatt’s interest in a Nineteenth Century article on childrearing and a Shakespeare tragedy, a time scale of centuries and—why not?—millennia. Is there an intrinsic ordering there as well? If so, what is that ordering about? Does the human mind develop, perhaps mature, and, dare I even suggest it? progress over the course of centuries? Are we allowed even to thing such thoughts without being struck dumb?

* * * * *

Meta comment: I've made no attempt to hide my affection for the newer psychologies in the study of literature. The subject of this post, however, owes little or nothing to those psychologies nor does it owe much to various post-structuralist approaches (I don't follow them), though I'd be happy to find out that some new historicists have something to say about it. Nonetheless it seems to me a matter central to the study of literature. It arose in my thinking simply from thinking about literary texts and relations between them.

Friday, March 9, 2018

Thursday, March 8, 2018

What’s Photography About, Anyhow?

This is from November, 2013. Do I still believe this? This is before I discovered shaky-cam, which was in the middle of 2014.

That’s something I think about a lot, though much of that thinking is in the form of the photographs themselves. I suppose the thinking began when I got my Canon point-and-shoot to photograph Millennium Park in Chicago. At that time I had no intention of becoming a serious photographer, but I nonetheless thought about what I was doing.

Things turned serious when I decided to pursue graffiti and got my trusty Pentax SLR. There the issue was: how do I photograph graffiti? I read advice that said to photograph it straight-on and four-square, no fancy stuff. That is, photograph it as though it were a painting hanging on a wall, any wall, somewhere. The focus is on the graffiti, not on what you as a photographer can do with a camera.

Fair enough. The trouble, though, is that graffiti isn’t hanging on any just wall. It’s not hanging at all; it’s painted directly on this or that particular wall. So that particular space becomes part of the experience of the graffiti. Context is important. Further, graffiti is often quite large so that moving back and forth, in and out, is part of your experience. All of this calls for context shots, and not just one or two, and detail shots of various scales. And what about time of day and season of the year?

At this point photographing graffiti is no longer so simple. It now calls on one’s powers of imagination and invention, one’s skills as a maker of images. That is, there is the graffiti writer’s skills, and there are your skills. What’s the (proper) relationship between the two?

Not obvious.

Meanwhile, I began photographing other subjects and I began experimenting with Photoshop. At first I was only interested in an accurate rending of what I saw. But just what does THAT mean? In some sense that’s physically impossible. There’s no way any photograph can match the light one sees with one’s eyes. Exact color fidelity is somewhere between impossible and meaningless. So just how do I handle color when rendering an image? Is it appropriate to boost the saturation and contrast? Why or why not? How much?

There’s no absolute answer to such questions.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)