In destinies sad or merry, true men can but try.

– Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

In scientific prognostication we have a condition analogous to a fact of

archery—the farther back you draw your longbow, the farther ahead you can

shoot.

– Buckminster Fuller

Birthdays are generally just that, even “major” birthdays, like my most recent

one, my 70th. They are an occasion for a celebration, perhaps a modest one,

perhaps not quite so modest – our house was crowded with dinner guests for my

father’s 50th birthday – perhaps even extravagant. I’ve never been to an

extravagant birthday party. Birthdays may also be a time for reflection, but

by no means necessarily so.

But in my experience birthdays rarely correspond to major life events. What’s

a major life event? Getting married, whether at a small civil ceremony before

a judge or an elaborate wedding with 100s of guests into the church and out to

the reception where a great band – like me and my colleagues in The Out of

Control Rhythm and Blues Band – performs for hours of dancing, that’s a major

life event. Climbing a mountain you’ve trained for over a period of years,

that’s a different kind of major life event. Graduating from school, or

completing basic training in the military, passing the bar exam, all major.

Years ago, in my early 20s, I was in a rock band called “St. Matthew Passion.”

It was our last gig, the sax player and I were jamming a whacked out intro to

“She’s Not There” and suddenly it all disappeared, me, the musicians, the

room, the world, all into a brilliant, but soft, white light. Only the light

and the music. It lasted what, half a second, a second, two seconds? Whatever.

Those few moments challenged me for years, changing my sense of myself and the

world.

Major life events come in all forms and durations, but they rarely coincide

with a birthday. Birthdays simply mark the passage of time.

That was a bit unusual because I generally write in the morning, and perhaps I

was motivated by my birthday to do something a bit different. But that’s all

it was, a change in routine. It’s no big deal; I do it all the time.

But then I realized, sometime in the afternoon, that this birthday IS a big

deal, and that I really can make it a big deal. How? By finishing my working

paper, Calculating meaning in “Kubla Khan” – a rough cut. Why is that

important, major milestone important? Because I’ve been working on it almost

50 years, all my adult life.

|

|

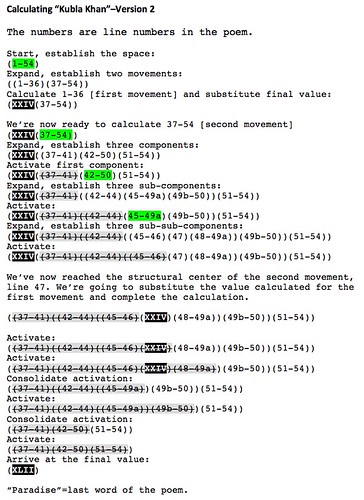

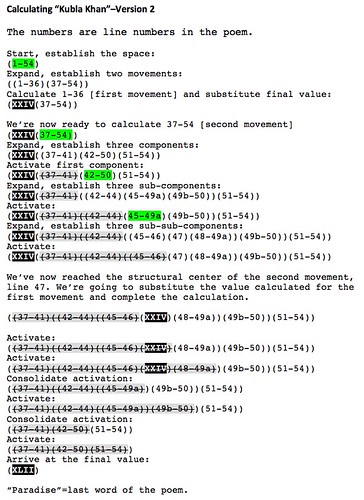

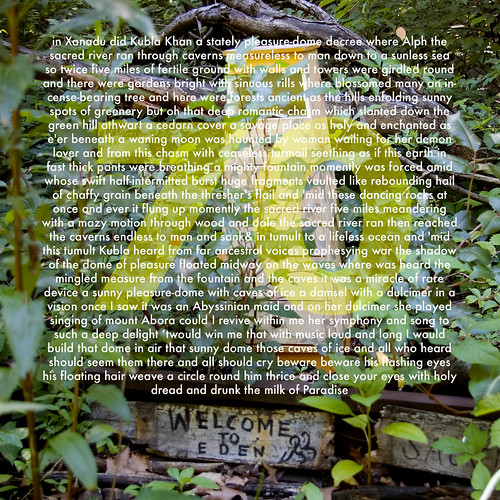

Teaser: Calculating meaning in “Kubla Khan”, 2017

|

This image likely makes little sense. Don’t worry about it. There are

two more images that won’t make much sense. Don’t worry about them

either. Just look at them as you would displays in a museum or gallery

and move on.

Not that paper, no, not that. It’s the poem, “Kubla Khan”, by Samuel Taylor

Coleridge, that I’ve been tracking all my adult life. I’ve been working on it

since the spring of 1969 when I read it in Earl Wasserman’s class in my senior

year at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore – where my father had gone

to school. To have completed a project that framed one’s adult life, that is

indeed a major event. Not completed, not in the sense that it’s all over and

done with – for it isn’t, but in some deep and fundamental sense, things have

changed. I’ve got a new understanding, and new obligations to go with it.

The first five lines:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

There are 49 more.

Let me explain. Perhaps then you will understand why I expect the next decade

to be the most productive one of my life. And not just my intellectual life.

There is the Bergen Arches Project as well. And who knows what else? I wonder

if Rita Moreno is available for salsa lessons?

The road to “Kubla Khan”

As William Wordsworth observed at the beginning of the 19th century, the child

is father to the man, so let’s go back to my childhood.

When I was seven or eight I received a toy. The toy came in a box. And the box

fascinated me. On the top of the box was a picture, and in the picture was a

boy. In the boy's hand was a box. And on the cover of that box was a picture.

In that picture was a boy. And that boy was holding a box. And on that box was

a picture. ETC. I would stare at that box and think, and stare, and think. For

I perceived that the pictures of boys holding boxes went on and on and on.

Only most of them were too small for me to see. But, though I could not see

them, I knew that they were there.

At about the same time I had my first cosmological idea. It seemed to me that

the entire world was but a motion picture which God projected onto a large

screen for the pleasure of His Son, the Baby Jesus – they were big on the Baby

Jesus in Sunday school; he was a very important little boy. Having figured

that out, I was puzzled. If we were images on a motion picture screen, then

how could we see one another, around one another? Motion picture screens were

flat, and so were the images projected on them. But I was not flat. My friends

and family weren’t flat. The house and yard wasn’t flat. The whole world

didn’t seem flat. How’d God manage to do that and how could the Baby Jesus see

it all?

As I grew older the questions changed. By the time I’d reached my early

twenties the questions focused on language, the mind, and literature. And then

I read “Kubla Khan”. Wham! That was it. I’d found a problem that

absorbed me. Yes, that’s a reasonable word, “absorbed”. It was bigger than me;

it took me in; it consumed me.

Explaining just how that was so, that’s not easy. It’s a technical matter. You

need to understand the intellectual context, and this isn’t the place to

explain that [1]. A crude analogy will have to do. The critical consensus is

that the poem is a colorful chaotic painting by a mad man. Beautiful, but

crazy. I’d discovered that, no, it was really an IMAX movie theater crafted

with the intricacy of a jeweled Fabergé egg by a team of highly skilled

artisans under the supervision of a master architect. Beautiful, intricate,

coherent, grand.

|

|

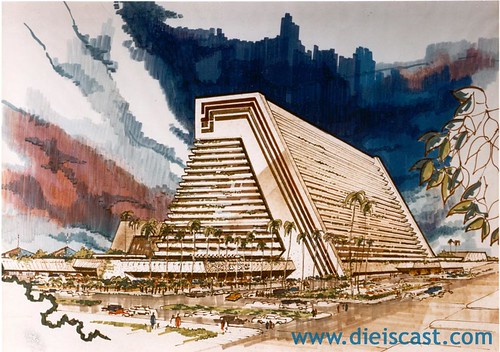

Back in the 1970s Donald Trump commissioned this hotel and casino

design from Martin Stern, Jr., a well-known Las Vegas architect. It was to be called Xanadu

[2].

|

The thing is, I could describe “Kubla Khan” from the outside, but I didn’t

know what was on the inside holding it up and causing it to turn on its axis.

The basic description was in place in my 1972 master’s thesis, which had been

directed by Richard Macksey of the interdisciplinary Humanities Center at

Johns Hopkins. A year later, in the fall of 1973 I went off to the State

University of New York at Buffalo to get a PhD in English. I was also hoping

to figure out the inner mechanisms of “Kubla Khan”.

|

|

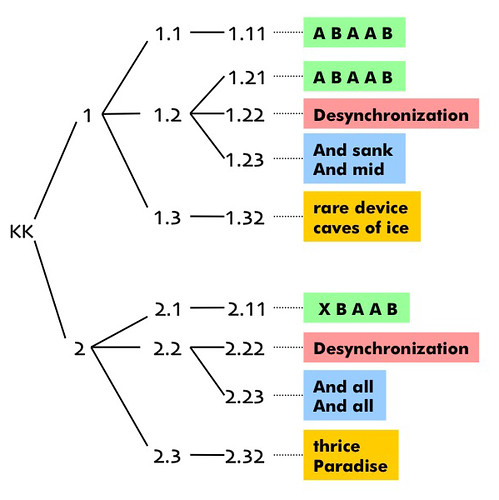

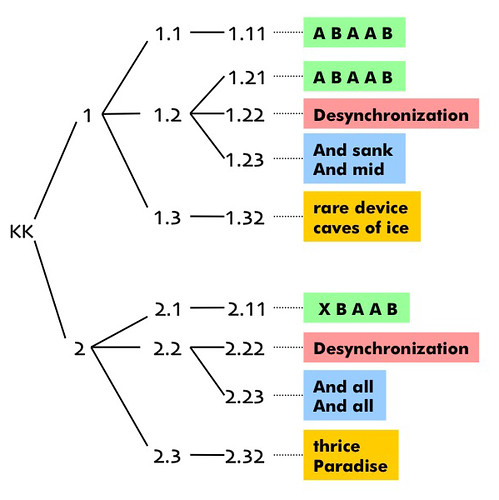

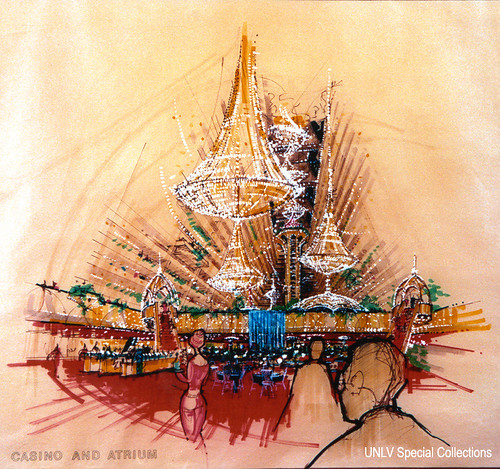

Cardinal points in “Kubla Khan”, 1972

|

Members of the English faculty read that master’s thesis and recognized that,

yes, there was something there. But they couldn’t help me figure it out. A

fellow graduate student, Ralph Henry Reese, introduced me to a professor in

the Linguistics Department, David Hays, who was one of the founders of

computational linguistics. Perhaps he could help me? Yes, he could, and did. I

worked closely with him and his students and learned a great deal; it was

perhaps the best learning experience of my life – well, next to years of

informal tutelage by my father. We figured out a Shakespeare sonnet, “The

Expense of Spirit”, but “Kubla Khan” remained an enigma.

By that time I’d decided that “Kubla Khan” was my touchstone, the thing I used

to test my knowledge and understanding of the human mind. For that’s what I

was really interested in, the mind. Literature was but a way of investigating

the mind.

My touchstone kept eluding me. I wrote articles on the brain, cognitive and

cultural evolution, metaphor, music, and Shakespeare plays – some of them in

conjunction with Dave Hays; we’d become fast friends and colleagues. I

published a book on computer graphics and imaging –

Visualization: The Second Computer Revolution (1989), coauthored with

Richard Friedhoff. A decade later I wrote a book on music,

Beethoven’s Anvil: Music in the Mind and Culture (2001). While working

on that book I consulted closely with Walter Freeman, a pioneering

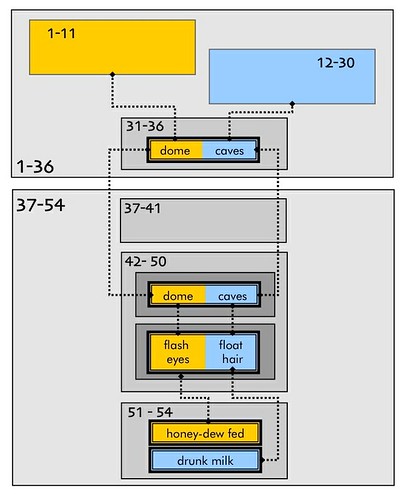

neuroscientist. Then I decided to take another crack at “Kubla Khan” [3]. Much

better, I thought, but not yet there.

|

|

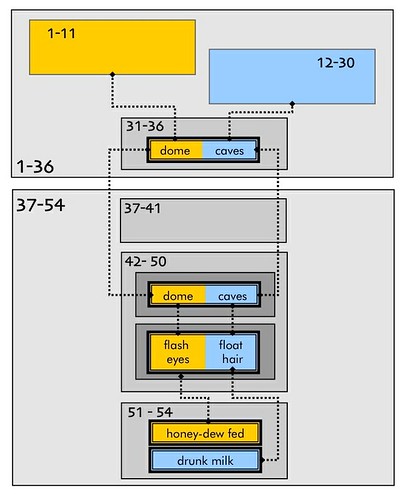

“Kubla Khan”, 2003

|

That was 2003. I couple years later I joined the academic blogosphere and

became a blogger at The Valve [4], a group blog about literature and

philosophy. I posted up a storm, and when The Valve shut down, I moved here,

to New Savanna, and continued posting. In 2010 or so I began gathering posts

into working papers and posting them to the web [5]. I was now, in effect,

self-publishing.

I kept thinking about “Kubla Khan”, of course, and had become interested in

animation after watching Disney’s Fantasia in connection with an

aborted book project. My friend Tim Perper then introduced me to Japanese

manga and anime – Cardcaptor Sakura, Metropolis (Tezuka’s manga,

Rintaro’s anime),

Sailor Moon, Azumanga Daioh, Ghost in the Shell, Spirited Away, Astroboy

and others. I had extensive correspondence with the late Mary Douglas, DBE,

FBA (Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire –

I kid you not – and Fellow of the British Academy), who got me

interested in ring-composition, which has become a central interest of mine.

And that interest has recently converged on, you guessed it, “Kubla Khan”.

Earlier this year I began having a Twitter conversation with James Ryan, a

graduate student working on computer games at the University of California at

Santa Cruz. He became interested in the work I’d done at Buffalo on

computational linguistics and poetry and invited me to give a presentation at

a workshop he’d organized in Portugal. So I wrote a paper and delivered a

presentation based on it early in the morning on Tuesday, November 14, 2017

[6]. As I couldn’t make it to Portugal I had to deliver the paper over the

Internet via Skype. The time difference meant that I had to get up at 4:30 AM

so I could shower, shave, and have breakfast in time for my presentation at

5:45 AM my time, but 10:45 AM in Portugal.

The presentation went well. In the question period Ryan asked me whether I

planned to get back to “Kubla Khan”. I forget exactly what I said, but it was

something like “maybe/I hope to/someday/yes”. Two days later I’d gotten back

to the poem and decided that, yes, I knew how it worked. I’d had a glimpse of

the mechanism. I could see the springs and gears.

More or less.

I quickly published some notes to the Internet (such as the

Teaser above), place keepers. Then I went to work explaining those

notes. I posted one draft on the web on November 29,

The problem of form in “Kubla Khan”, in which I stated the problem,

sorta’ [7]. I then set to work on another paper in which I intended to outline

a solution. That paper grew and grew until I called a halt and decided to

regrounp. I started working on the new document on the 5th or 6th, I don’t

remember just when.

And this brings us back to where we began. On December 7, my 70th birthday:

I woke up, cruised the web, made four posts to New Savanna, had breakfast

and then, and then I decided to go out and take some photos, including some

of that green platform pump I’ve been having so much fun with. That was a

bit unusual because I generally write in the morning, and perhaps I was

motivated by my birthday to do something a bit different. But that’s all it

was, a change in routine. It’s no big deal; I do it all the time.

But then I realized, sometime in the afternoon, that this birthday IS a big

deal, that I really can make it a big deal. How? By finishing my working

paper, Calculating meaning in “Kubla Khan” – a rough cut.

And that’s what I did. The fact is, I didn’t quite finish it that day. My

brain was frazzled by six or seven in the evening, but I’d completed the guts

of the paper, the part about “Kubla Khan”. I cleaned up the last details

(about a contrasting poem) the next day, December 8, and posted it to the web

[8].

And so there it is, my life’s project, done. Well, sure, I’m going to have to

write a book on Coleridge, and the book may not work out – it’s not done until

it’s done. Still, as far as I’m concerned, I’ve taken this as far as I can.

I’ve satisfied the hunger that sent me off to Buffalo over four decades ago.

From this point on it’s up to others to take it farther – and it must be taken

farther. When the book is written – it’ll take a year, maybe two depending on

what else I’ve got to do, which is likely quite a lot – I will have fulfilled

my responsibility to that quest.

What’s curious is that there are no concepts in the papers that I didn’t have

at hand, say, five or even ten years ago. Why’d it take me so long to put the

pieces together? I don’t really know, but I offer two observations: 1) One of

the pieces is the mathematical idea of convolution, which David Hays and I had

used in a paper we’d published in the mid-1980s. I’d seen it in recent work on

“deep learning”, so it was newly relevant. 2) I was asked. A small group of

people I hadn’t know about six months before wanted to know what I’d been

doing back in the 1970s. If the world was now asking about my work, perhaps

there was something there I hadn’t realized. I looked, and SHAZAAMM!!,

I found that something.

What’s next? I can think of perhaps five academic books I could do, including

the Coleridge book. But I’m not sure I really want to write all of them. I’ve

got to do the Coleridge book, and there’s a book on cultural evolution I’ve

got to do – as far as I can tell, no one else is in a position to do it. As

for those other books, much of the material is already out there on the web in

the form of working papers. Gathering those papers into books would allow me

to tighten things up a bit, but it’s pretty accessible as it is.

And then there’s the notes I’ve done on attractor nets [9]. They need a lot of

work, or I could simply abandon them. But I need collaborators to take that

project farther, people with technical skills I don’t have. I’d like to find

some suitable people and get on with it. And, frankly, I’d be interested in

making that a commercial venture, though it would be a long shot.

But then there’s the Bergen Arches Project. That’s a different story; I figure

it will take up a good deal of my time over the next decade. Before we get to

it, though, you need to understand how Jersey City became my home.

Making Jersey City my home

When Dave Hays died in 1995 – lung cancer – I had to reestablish contact with

the mid-1970s gang. One of them, Bill Doyle, was starting a new company,

MetaLogics, and he wanted me to be part of the team. The company was to be

based in Hoboken, NJ, so I moved to Jersey City, which bordered Hoboken to the

south. When the company died in the dot-com bust of 2001 I decided to remand

in Jersey City.

Late in 2003 I was attending a meeting of a seminar, Computers, Man, and

Society, held at the Faculty House of Columbia University. Another member of

the seminar, Takashi Utsumi, had brought a guest, Jerry Greenberg. Jerry

explained a project he was working on, called World Island. The idea was to

create a “permanent world’s fair, for a world that’s permanently fair” on

Governor’s Island, in New York Harbor just off the southern tip of Manhattan.

It was to be a combination of hotels, an ongoing trade show, restaurant row,

an arts and crafts fair, museum, meeting place, and a whole lot more, with

orchids woven throughout. Why orchids? Because, said Jerry, we know that “when

the orchids go, we’re next.” I was entranced by the vision, scope, and poetry

of the project.

I also figured it would be an opportunity for some interesting consulting

money. I made appointment to meet Jerry at his office just off Union Square in

Manhattan. It quickly became obvious that he didn’t have two dimes, well,

quarters, to rub together, but that he had attracted the interest of people

with real money. His presentation materials had been professionally produced

and, as I said, the project was fascinating.

|

|

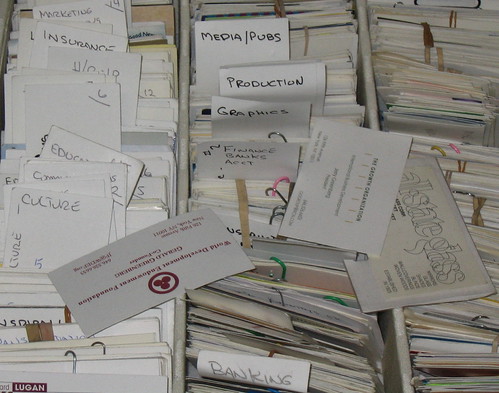

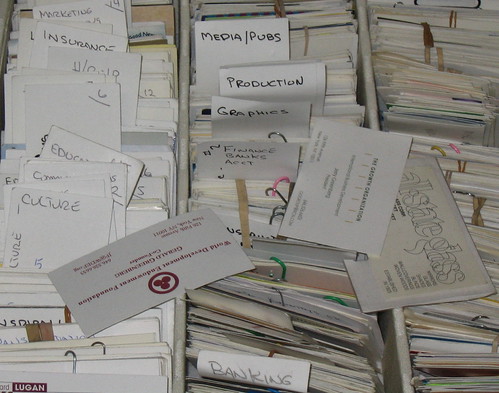

Jerry’s World Island Database

|

So I decided to go along for the ride, to see what’s up. I schemed with Jerry,

did research, and refined his presentation materials. And I attended meeting

after meeting with a remarkable range of people, Wall Street financiers,

expatriate Russian inventors, German businessmen, theatre executives, a

billionaire New York real estate mogul (not Donald Trump), heads of NGOs, and

a motley crew of creatives in a wide variety of disciplines. All willing and

even eager to listen to this 20, 30, 40, 50 billion dollar (the number

fluctuated, but generally got larger over time) plan for a non-profit real

estate development in New York harbor [10].

In the summer of 2004 I was scheduled to attend a conference in Chicago to

deliver a plenary talk on “Music, the Mind, and Language”. I took a small

point-and-shoot camera with me so I could take photographs of the newly opened

Millennium Park [11], which seemed a useful model for some aspects of the

World Island Project.

|

|

Millennium Park, Chicago

|

Now I owned a camera. I’d bought it for one specific purpose. Now what? Should

I take more photographs? Of what, and why?

I’d walk around the neighborhood taking photographs of this and that,

including this:

It was right across the street from me. I thought it was pretty cool. I

figured there must be more of that around here. I went looking.

And almost immediately I found this:

It was 18 feet wide, seven feet tall, and stood next to an active freight

line. When trains went by the sound was deafening and it went on for five or

ten minutes – these trains were long. The freight cars were covered with

graffiti.

I decided I would document graffiti Jersey City. I bought a better camera and

went to work, shooting hundreds and thousands of picture of local graffiti. It

changed my life. It made Jersey City my home.

* * * * *

Jersey City is where I lived, I’d lived there since 1997 or 98. But living in

a place doesn’t make it a home, home is something deeper. Home is about your

soul, for want of a better word.

I was, and am, a bachelor. I’ve never been married, and don’t have any

children. A wife and children create a home. They are more than you; your

commitment to them extends your vital concerns beyond yourself. Moreover they

will be involved in social circles other than yours; those circles – I’m

thinking particularly of your children’s friends – commit the family to a

physical place. Nothing committed me to Jersey City in that way.

I am an independent scholar. I write and publish books and articles; I hang

out on the Internet and interact with scholars around the world. That’s where

I am rooted, that is my (spiritual) home. All that stuff about “Kubla Khan”,

and poetry and whatever else, that’s my soul, that’s the thing bigger than me

that connects me to the world. I can participate in those activities no matter

where I am physically located.

When I committed myself to photographing, to documenting graffiti in Jersey

City, that commitment made Jersey City my home. It embedded my interests as a

scholar and thinker in the physical infrastructure of the place where I lived.

It was graffiti that brought me to attend a meeting of the Hamilton Park

Neighborhood Association (HPNA), where I found out that many of my neighbors

had a different attitude toward graffiti than I did. That’s understandable,

and that’s OK.

I helped the HPNA with a small project to transfer the association’s papers to

the local branch of the library. It was there that I saw a file of newspaper

clippings about the Bergen Arches. What’s that, I thought,

what’re they?

A bit later some graffiti writers told me about another graffiti site, “below

Dickinson, near the Wall of Fame.” So I poked around and there it was:

That just HAS to be the Bergen Arches, I thought. Yes, there was

graffiti there:

But there was also ‘nothing’, not really nothing, but no city.

Of course, I’d seen such places all my life, here and there. Growing up in

Johnstown, Pa., my father would take me hiking in Stackhouse Park, in

Westmont. We’d pull off the side of the road and enter through a parting in a

wall of tall grass, bushes and trees. There we’d walk in a small ravine on

ground cushioned by pine needles, the trees over head, and a small brook

jumping from rock to rock. There was a similar place near our home on Luther

Road, about a half mile away, near the mink farm (as we kids called it). Tall

pines, cool shade even in the middle of summer. There was a more generous and

more mysterious ravine near the YMCA summer camp I went to, but not

forbiddingly large. I made a painting of it, though in a very abstract style.

It hangs in my sister’s dining room:

Coleridge wrote about such a place in “This Lime-Tree Bower”, which he wrote

at roughly the same time he wrote “Kubla Khan”. Here’s a passage:

They,

meanwhile,

Friends, whom I never more may meet again,

On springy heath, along the hill-top edge,

Wander in gladness, and wind down, perchance,

To that still roaring dell, of which I told;

The roaring dell, o’erwooded, narrow, deep,

And only speckled by the mid-day sun;

Where its slim trunk the ash from rock to rock

Flings arching like a bridge;–that branchless ash,

Unsunn’d and damp, whose few poor yellow leaves

Ne'er tremble in the gale, yet tremble still,

Fann’d by the water-fall! and there my friends

Behold the dark green file of long lank weeds,

That all at once (a most fantastic sight!)

Still nod and drip beneath the dripping edge

Of the blue clay-stone.

Is it physically the same as those other places? How should I know, I’ve never

been there. And those other places, Stackhouse Park, the mink farm, YMCA camp,

they weren’t the same, physically. But the mood, the myth, the meaning, the

same. All of them.

And yet the Bergen Arches wasn’t a natural formation. It had been blasted out

of the Jersey Palisades with 125 tons of dynamite. It took five years. They

laid four railroad tracks there, and those tracks took trains to the Hudson

River into the early 1960s. And then three of the four tracks were pulled out

– why not the fourth? – and the Arches were closed, abandoned, and forgotten.

But homeless people lived there, urban explorers trekked there, and graffiti

writes got up (as they say) on the masonry walls of the arches. It was home to

social networks running counter to mainstream society. In a sense, it was a

foreign overlay on and intrusion into the urban environment of Jersey City.

* * * * *

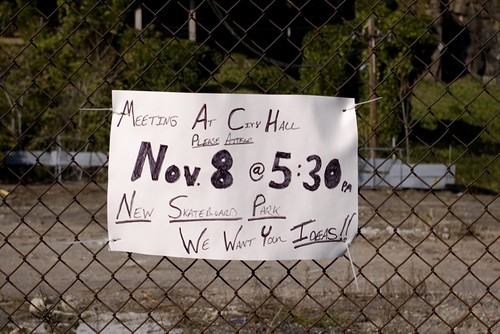

There’s a site about a quarter of a mile away from the Arches where I found

some first class graffiti. This site was also a do-it-yourself skate park. One

day in October of 2007 I arrived at this site to find the floor slab broken

up. The skate park was destroyed. On November 4, 2007, I saw this sign:

That set off the chain of events that would, almost a decade later, result in

the Bergen Arches project.

The Bergen Arches Project

I decided to attend the meeting, more out of curiosity than anything else. I

put on my banker’s suit and showed up. As I’d suspected, the meeting had been

called by the young councilman, Steve Fulop. Only four skate-boarders were

there, not enough to do anything. But they agreed to get more people out for a

meeting two weeks later. That meeting drew 30 skateboarders plus parents and

others. Fulop agreed to talk with the New Jersey Thruway authority to see if

the City could build a park beneath the I78 extension through the City and I

volunteered as liaison between the councilman and the skateboarders.

Without going into the details let’s just say that things didn’t work out, but

the process got me thinking [12]. The result of that thinking was a proposal

[13] to build a series of parks that spanned Jersey City roughly two miles

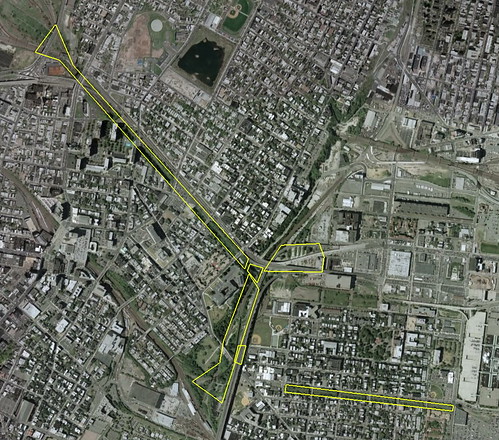

from east to west, areas outlined in yellow in the following map:

See that long narrow strip extending roughly from the center of the map to the

upper left? That’s the Bergen Arches. It’s about a mile long. I guestimated

that the whole project would cost a quarter to half a billion dollars and

could bring in 90 million a year in tourist revenue. I had no way of pursuing

the project, not something that large, but I circulated the report among

friends, gave a copy to the councilman, and put it online where the curious

could find it.

Why did I write the report if I had no way of pursuing the idea? Because it

was fun, serious fun. A way of playing around with possibilities for the

future. Maybe I couldn’t pursue the project, but who knows? Others might.

Do you remember that crazy World Island project I’d been working on with

Jerry, now Zeal, Greenberg? That’s where I got the idea for this two mile

string of parks in Jersey City. That’s where I learned to think about a city

as a coherent, if complex, object.

I continued to work with Zeal, with my writing, with my music – there was a

Saturday afternoon jam session on the Upper West Side of Manhattan I went to

for several years, and I continued photographing Jersey City graffiti. I moved

to a different Jersey City neighborhood, Bergen-Lafayette, where my interest

in graffiti led me to Greg Edgell at 51 Pacific Avenue. He curated a 5000 sq.

ft. loft there and the alley behind the whole block.

I showed him that proposal,

Jersey City: From a Skate Park to the World. He was skeptical, and

properly so. My response:

Yep, it’s crazy. But the world changes. I grew up during the Cold War and

figured it would still be going when I died. And then the Berlin Wall came

down. Shazam! The world had changed.

Greg bought it.

We worked on a variety of projects over the next few years. Well, Greg worked;

I advised and took photos. A block party on Pacific Avenue, an emergency mural

at the Liberty State Science Center, campaign headquarters for Councilman

Steve Fulop (who ran for mayor and won), murals and events all over the place.

Green Villain – the name under which Greg and his floating crew of associates

worked – was becoming established, not only in Jersey City, but New York City

too.

The largest project involved turning a shuttered Pep Boys store into a

temporary graffiti gallery, for a week (inside) and a month (outside) before

the building was demolished to make way for new construction. We called it the

Demolition Exhibition. It made the Wall Street Journal [14].

That was late summer of 2015. What next? It was Greg who asked the question

and early in 2016 he came up with the answer: The Bergen Arches Project. This

was out of that report I’d written – in a spirit of high ludic seriousness –

back in November of 2007, the report I used to introduce myself to Greg, the

report he thought was crazy, and I agreed. As Louis Armstrong sang, what a

wonderful world, and Israel Kaʻanoʻi Kamakawiwoʻole (aka Brother Iz) sang it

too.

It didn’t make sense to tackle the whole two and a half miles; for one thing,

part of that strip had been in litigation for the last decade and a half. No,

the Bergen Arches was quite enough. It was and is a single coherent piece of

real estate. Greg contacted some architect friends of his; they had some

design ideas and produced some renderings; and we launched a website in the

late summer of 2016 [15]. We were live.

There’s no need to go into any detail about what happened next. It’s

sufficient to note that we got a bit of buzz in Jersey City, we’ve talked with

neighborhood associations, architects, activists, and city officials and

politicians. We’ve assembled a small core team, including a young architect,

Rahid Cornejo; a dyed-in-the-wool Jersey City activist; Dan Levine, and our

lawyer, Judith O’Donnell. And we have formed a non-profit, Bergen Arches, a NJ

Nonprofit Corp. We’re figuring it for a ten-year ride. However it ends – who

knows? – it’ll be fun. And hard work.

What’s next?

That’s where I am as I head into my eighth decade. The way it looks to me,

here and now as I write this early in the morning of December 18, is that I’ve

got to phase out the intellectual work and devote more time and effort to

other things, the Bergen Arches certainly, but also music, photography, and

Charlie Keil’s projects – which I’ve not mentioned, but, whatever; they’re

important too.

“Phase out” doesn’t mean drop it like a hot potato. What it really means is

transmit the knowledge. While the world certainly has not rewarded me for the

time and effort I’ve put into my intellectual work, it did somehow manage to

afford me the time and resources to do it. I’ve got to repay that debt. I’ve

got some more writing to do, just how much is not clear. But I’ve also got to

create an institution of some kind, a modest one, that can carry on the

intellectually independently of me – at the moment, I figure the academic

world is a lost cause. Just what that will be, I don’t know, but that’s OK.

It’ll come in time.

I have no idea what will happen with the Bergen Arches project. That too will

come in time. And then there’s Rita Moreno. When she calls, I’ve got to have

my dancing shoes on.

* * * * *

“We’re in one of those great historic periods…

when people don’t understand the world anymore…when the past is not

sufficient to explain the future.”

– Peter Drucker

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can

change the world; indeed it is the only thing that ever has.

– Margaret Mead

* * * * *

Concerning the image at the head of the article: The “70” is obvious enough.

The white text is “Kubla Khan”, without punctuation and line divisions. The

underlying photograph is a small shrine someone had placed in the Bergen

Arches several years ago. Notice the greeting at the bottom:

Welcome to Eden.

References

[6] Here’s the workshop page:

First Workshop on the History of Expressive Systems, November 14, 2017,

at the International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling (ICIDS),

Funchal, Madeira, Portugal,

http://www.expressive-systems.org/hex/01/

As you say, "The best is yet to come."

ReplyDeleteYes. These are the good old days. The best is yet to come.

DeleteWhat a fantastic post, Bill. You drew back the bowstring so well, setting us up for your deft meditation on place. Bravo, sir.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Bryan. And now, it's the New Year and the next decade of my life. Got to start delivering.

DeleteI hear you. Back to work for me, too.

Delete