I’ve recently finished a submission for the First Workshop on the History of Expressive Systems:

By 'expressive systems', we broadly mean computer systems (or predigital procedural methods) that were developed with expressive or creative aims; this is meant to be a superset of the areas called creative AI, expressive AI, videogame AI, computational creativity, interactive storytelling, computational narrative, procedural music, computer poetry, generative art, and more.

And that got me thinking about my intellectual genealogy.

Here’s some notes, some diagrams, and some light commentary, just enough to give some idea of who these people are, how they’re related to one another, to me, and to expressive systems. If you want more information on these people you know what to do.

1° of separation: Core connections

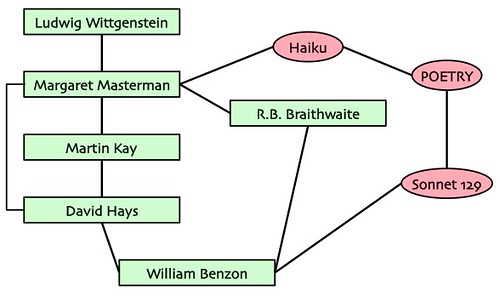

Back in the ancient days Margaret Masterman studied with Ludwig Wittgenstein in the 1930s. Sometime after that she established the Cambridge Language Research Unit (CLRU). She also married R. B. Braithwaite, a philosopher.

Meanwhile David Hays had gotten his degree at Harvard and took a job at the RAND Corporation, where he headed up the machine translation program starting in the mid-1950s. It is through MT, presumably, that he came to know Masterman, whose CLRU was doing important work in linguistic computing. Martin Kay had taken a job there in 1958 and Hays hired him to work for the RAND MT program in 1961.

In the late 1960s the CLRU had done some work on a Haiku generator – that’s Masterman’s connection with expressive computing. Meanwhile she had written a now classic essay on Kuhn’s concept of a paradigm, “The Nature of a Paradigm”. I read that sometime in the early 1970s and was quite impressed; she catalogued 22 different senses in which Kuhn had used the word.

But before that, I had taken a course in decision theory taught by Braithwaite. He was visiting at Johns Hopkins in 1968-69 and, as a philosophy major, I was urged to take the course. We were given that he was a major figure. Also a bit eccentric. I knew nothing about his relationship with Masterman, nor do I learn anything about her relationship with him when I read the Kuhn essay. Those were different worlds and different people.

By the mid-1970s I was at SUNY Buffalo and working with David Hays and his students in computational linguistics. In particular, I was working on Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129, “The Expense of Spirit.” That’s my connection with expressive computing. I didn’t implement anything, but I took a computational view in the kinds of things expressive computing is about.

One day I was at Hays’s house – perhaps working on putting out an issue of the American Journal of Computational Linguistics (AJCL) – and we were talking about things and stuff. He said that he’d had in interesting and possibly important idea about consciousness, but that it was so crazy he was reluctant to tell it to anyone for fear they’d think he’d gone off the deep end. There was, however, one person he trusted.

Who?And then he told me about her and computational linguistics and Martin Kay – I already knew about him; he typeset some pages of AJCL on his Xerox Alto (he was working at PARC at the time) – but I didn’t know about Masterman. He also informed me that she was the one who knitted that white sweater he wore so often in cool weather. I suppose that’s when I learned that she was married to Braithwaite.

Margaret Masterman.

Margaret Masterman! You mean THE Margaret Masterman?

Yes.

Computing stories

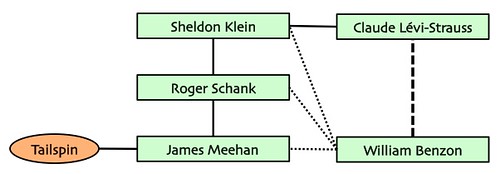

As I have explained many times, the work Claude Lévi-Strauss did on myth has been a major influence on my thought.

During the mid-1970s I was bibliographer for AJCL. The gig required me to read the current literature in computational linguistics and prepare abstracts for the journal. As editor Hays got tech reports from all the major research projects and turned them over to me. Thus I read everything that came out of Roger Schank’s lab at Yale, including the original reports on James Meehan’s Tailspin system, one of the earliest story generators.

I also got reports from Sheldon Kline’s work on a ‘myth’ generator, some he’d done with Lévi-Strauss himself. Given my interest in Lévi-Strauss, those reports should have been more interesting to me than they were. The problem is that Kline’s generator seemed to owe more to Propp than to Lévi-Strauss. It had always seemed to me that, 1) Propp’s functions were the product of deeper mechanisms, and 2) Lévi-Strauss was much closer to those mechanisms that Kline was. Alas, Lévi-Strauss didn’t really know how to formulate those deeper mechanisms. As far as I know, no one has figured that out.

I don’t know when and where I learned that Schank had trained with Kline.

In any event, I knew of that work and cited it where appropriate, but it didn’t have much influence on me. It’s about the specific mechanisms and structures of computation. Hays’s model was more to my liking. Of course I am not unbiased. By that time I had been working with Hays enough that I had made a contribution or two to the model.

We knew one another

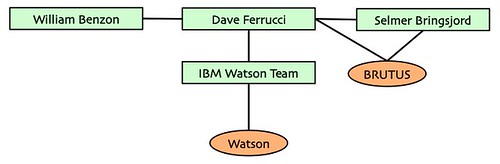

When I left SUNY Buffalo I took a job in Language, Literature, and Communication at RPI (Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute). I ended up as a faculty advisor on knowledge representation for CIM (computer integrated manufacturing) with the CMP (Center for Manufacturing Productivity). There I met and worked with a young master’s student named David Ferrucci for a semester or two. Then I left RPI.

Ferrucci left RPI to work at IBM. Sometime in the 1990s he worked with Selmer Bringsjord, an RPI cognitive scientist, on BRUTUS, a story generating system in the symbolic-computing style of classic AI. A decade later he led the team that built Watson, the question-answering system (QA is a classic AI problem), that beat the reigning Jeopardy! champion on nationally televised TV. Watson was built in the newer everything-but-the-kitchen-sink Big Data style. Ferrucci has now left IBM and is working on an approach that combines the symbolic knowledge-based AI with the newer style. His company is called Elemental Learning.

BRUTUS, of course, is an expressive system. Watson, though, is questionable. Still, Jeopardy! is an entertainment program, and that’s what Watson did in that context, entertain.

Ferrucci and I still exchange an occasional email.

No comments:

Post a Comment