In what way is Godzilla, King of the Monsters, like Wuthering Heights? You might think that they are so different that their resemblances are of little account. Sure, they’re both about people in conflict, but other than that... After all, one is a classic text of English literature written in the early 19th Century. The other is an Americanized version of a mid-20th Century Japanese creature feature that has spawned almost 30 sequels, all about monsters.

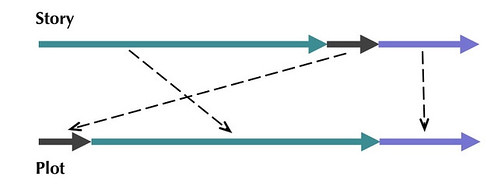

Yes, they ARE very different texts. But they are alike in a very profound way: form. Consider the following diagram, which applies to both texts:

The upper line divides indicates story in temporal order, from first (on the left) to last (on the right). The line shows these events divided into three segments. The lower line depicts how those three sets of events are re-ordered in the text.

Thus both stories have a certain sequence of events that happens relatively late in the overall sequence. As the stories are actually narrated, however, this late sequence is moved to the beginning and the other sequences are adjusted to accommodate. In both cases the sequence that is moved involves a narrator external to the main sequence but known to the characters in it.

Godzilla, King of the Monsters (1956) is an Americanized version of the original Japanese Gojira (1954). Large chunks of the Japanese original were removed and new footage shot involving an American reporter, Steve Martin. Martin is in Tokyo on his way to report a story in Cairo. While there he decides to visit some friends and Godzilla appears. He reports on the story as it develops and is injured when Godzilla finally attacks Tokyo.

The film opens with shots of a wrecked Tokyo. We see Martin in the wreckage of some building; then he’s on a stretcher; and he’s finally placed the on the floor of a hospital. He sees one of his friends and they talk. She leaves to get a doctor and he begins recalling the story from the beginning.

In Wuthering Heights the outsider is a man named Lockwood. He’s come to rent a house, Thrushcross Grange, for the summer and meets the principal characters in another house, Wuthering Heights. He then hears a story about two generations of love and loss from one of those characters, Nellie Dean. But, like Steve Martin, he plays no causal role in the events he’s narrating.

In the abstract, one could imagine that the filmmakers who Americanized the Japanese film, Gojira, were influenced by Brontë’s text. But that seems implausible to me. The more plausible explanation is that they faced a similar problem and so arrived at a similar solution. We know the problem the American producers faced; they had to present a Japanese story to an American audience, and when the two countries had recently been at war. It’s not obvious to me just what problem Brontë faced. Did she regard her core story as being so strange that she had to create Lockwood to hear it from Nellie Dean and then tell it to her audience? If so, why?

These two stories are alike in another respect: one of the principle characters in each is an outsider to the world where the story is set. In Wuthering Heights it is Heathcliff who is the outsider. His background is obscure. We know only that he came from the city. He’s depicted as wild and impetuous, almost feral. In Godzilla, King of the Monsters, it is Godzilla who is the outsider. This resemblance suggests something about why the story has to be told through an outsider, something requiring further thought.

* * * * *

Given my interest in form, this case is intrinsically interesting to me. I want to know how this form works.

But I’m also interested in the fact that this resemblance is a superficial one, superficial in then sense that it is readily apparent. You don’t have to undertake an extensive and possibly problematic analysis to discover this similarity between these two texts. The resemblance is available to simple and straightforward descriptive means.

But it was largely fortuitous that I happened to notice this resemblance. If recent posting had brought not Wuthering Heights to mind at a time when I’d just finished working on Gojira, I might not have noticed this resemblance. The academic study of culture is organized in such a way – along nationalist lines, Popular culture vs. high culture – that few researchers are unlikely to be interested in such very different texts.

Not only do we need to place more emphasis on description, to ride a favorite hobbyhorse, but we need to undertake extensive comparative work encompassing all texts regardless of their origins.

No comments:

Post a Comment