01:45:17

The marriage between Naoko Satomi and Jiro Horikoshi is notable on several counts. In the first place, marriage is a major life event and a large number of stories are oriented around it. A romance may or may not actually depict a wedding at the end, but when it isn’t depicted, it is implied. This particular wedding doesn’t happen at the very end of the film, but it is quite near the end.

Secondly, I don’t know quite how to read it. That puzzle has two aspects. While I am generally familiar with Western marriage ceremonies and their depiction in film, I’m not very familiar with Japanese customs, though I know something. In consequence, I have little sense of how a Japanese audience would read the ceremony Miyazaki depicts. Would members of a Japanese audience see that ceremony as somehow unusual or exceptional or is it well within standard (movie) practice?

Beyond the ceremony itself, we have the way in which the marriage was contracted [1]:

Until the 1940s, almost 70 percent of all marriages were arranged (お見合い omiai). The modern system of marriage has adjusted to pressure from the Western custom of love marriages (恋愛結婚 ren’ai kekkon), which surpassed arranged marriages in number in the mid-1960s. The acceptance of the love-match meant that households, and in particular the parents of a young couple, did not have the final say in the marriage anymore.

Their marriage is not arranged, but Naoko’s father is fully aware of developments in their relationship and Horikoshi initially broached the issue of marriage with him, not Naoko, though she was within earshot (when they were in the dining room at the mountain retreat). We know nothing of her mother nor of his parents. In a sense, though, the Kurokawa’s are ‘standing in’ for his parents, as he was living with them at the time.

Why was he living with them? Because he was hiding from the Japanese secret police. Why was he hiding from the secret police? Because he had been seen consorting with an anti-Nazi German. When and where had he been doing that? When he was at that same mountain retreat where he met and courted Naoko. And that German even played a minor facilitating role in their relationship.

Do you see what’s going on here? If so, please tell me. It’s complicated, no?

Moreover their relationship follows a convention common in anime and manga. This convention is that of two lovers meeting prior to full adulthood – often in connection with marital arrangements made on their behalf by their parents, becoming separated until they reach adulthood, and then meeting again. At this time they may or may not recognize their childhood connection but in any event they fall in love and, in course, become married. That’s not a Western romantic trope and so I don’t how to read it. More to the point, I don’t know how Miyazaki’s Japanese audience would read it.

I do sense, though, that while arranged marriage is no longer the norm in Japan, it is still practiced in Japan and the transition to love marriages (恋愛結婚 ren’ai kekkon) is recent enough that the nature of the relationship between Naoko and Jiro would register with a Japanese audience in a way that it doesn’t with a Western audience. In this respect Miyazaki is making a statement about their relationship that resonates more deeply in Japan than it does in the West.

Naoko Wants to Get Married

Let’s begin by recognizing that the move toward the actual marriage was initiated by Naoko. Yes, Jiro proposed, but at the time Naoko asked him to hold off until she had recovered from her tuberculosis. She went – yes, into the mountains – to a sanatorium. It’s while she’s there that Miyazaki initiates the sequence.

It begins with a shot of Mount Fuji, thereby identifying her with Japan:

01:38:27

Yet, as a woman with an illness that may well kill her, she is at the same time an outsider to normal Japanese society. This is a delicate game Miyazaki is playing. It’s as though her outsider status makes it easier to summon her to quasi-symbolic duty – though she’s quasi-symbolic to us, the audience, not Horikoshi or any other characters in the film. To them she’s a real person.

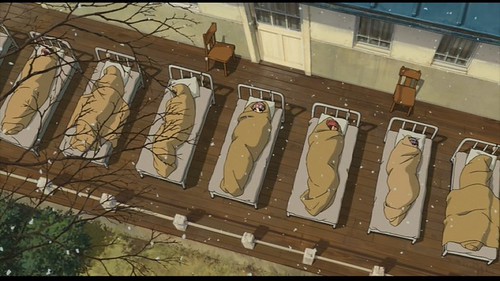

The camera zooms into the sanatorium and then to patients lined up on a porch wrapped cocoon-like in blankets. Naoko receives a letter and we see her reading it (notice the snowflake near the angle where her cap meets her robe, though I know it’s a snowflake only because I see it moving). Is she in a symbolic womb?

01:39:05

The camera cuts back to a shot of nearby trees...

01:39:08

... cuts to Naoko...

01:39:15

... and then cuts to an overhead view and zooms slowly back so we can see them, lined up cocoon-like, on the porch as the snow falls lightly. What is Miyazaki doing here?

01:39:20

He then cuts to this scene, a train moving across a bridge (an image we’ve seen several times before), during a snowfall in the early evening:

01:39:27

We see Naoko leaving the building, the next day presumably, and Jiro gets a phone call at work. It’s from her father. And in short order he’s meeting her at the train station:

01:41:26

Before you know it, he’s presenting her to Mr. and Mrs. Kurokawa:

01:42:10

01:42:20

Horikoshi: “Mr. Kurokawa, we have a request.” Miyazaki cuts directly to a new shot, with a conversation already started:

01:42:27

Mrs. Kurokawa: “We have plenty of room here.”Mr. Kurokawa: “I know we have the room. That is not the problem. I simply can’t approve of an unmarried couple living under this roof.”Horikoshi: “Then we will marry tonight. Mr. Kurokawa, Mrs. Kurokawa, will you please be our witnesses.”Mr. Kurokawa: “What?! Tonight!”Mrs. Kurokawa: “Of course we will dear. Naoko’s traveled all this way. It’s the least we can do.”Satomi: “My doctors know about this. And my father has given his blessing.”Horikoshi: “Please, help us.”Mrs. Kurokawa: “The bride and I have a lot of work to do, and so do you.” [Looking at her husband.]

The two women exit and chat for a second. We cut back to the men:

Mr. Kurokawa: “If you care about her at all, Jiro, you’ll send her back on the morning train.”Horikoshi: “I would have to give up the fighter project, Mr. Kurokawa, because I would go with her.”Mr. Kurokawa: “Is that your heart, or your ego talking?”Horikoshi: “Naoko doesn’t have much time. We’ve made our decision.”Mr. Kurokawa: “I see. [standing up] All right! So I guess it’s on with the wedding.”

Notice, first of all, that when Mr. Kurokawa attempts to bring Horikoshi to his senses, Horikoshi makes it clear that he’ll give up his work to be with the woman he loves. Given how the film has centered on his love of airplane design, that’s an extraordinary statement for him to make.

Does he really mean it? Since Kurokawa relents, we don’t know. Nor, I would submit, does Horikoshi. A bit later his sister will upbraid him for neglecting his wife – who puts rouge on her face so he won’t worry – in favor work. But this is common enough among men who are strongly driven in their work. It doesn’t mean they don’t love their wives. Perhaps they do, perhaps not. Cases vary. What it does mean, always, is that life is tough and we can never get all we’re capable of desiring.

Secondly, the legalities: what constitutes a legal marriage in Japan? This marriage would have been governed by the Meiji Civil Code of 1898, paragraph 775:

A marriage takes effect upon its notification to the registrar.A notification must be made by the parties concerned and at least two witnesses of full age, either orally or by a signed document.

In this case, the Kurokawas will be the required two witnesses.

The Ceremony

As for the ceremony itself, it’s window dressing. I consulted Gilles Poitras, an expert on manga and anime. Here’s what he told me:

The little ceremony has elements I have seen in TV dramas and live action movies. To me it seemed to be an improvised ceremony with traditional elements. Today ceremonies are not part of the legal requirement for marriage. As long as a couple meets the proper relational distance and are old enough all they need to do is fill out the paperwork and turn it in, even via mail slot after hours.

Immediately after Mr. Kurakawa has proclaimed that the wedding is on, we cut to a scene where Mrs. Kurokawa leads the bride back to the chamber where Horikoshi and Mr. Kurokawa are waiting. She slides the door open:

Mrs. Kurokawa: “Hear me! I bring to you a lovely maiden who has come from the mountains to be with her beloved. She has given up everything for him. What say you?”Mr. Kurokawa: “Here me! The man I present is an insensitive chucklehead without even a home to call his own. But, if that’s what she wants, she can come in.”Mrs. Kurokawa: “And then, they shall exchange the sacred vows.”

She puts out her lantern, throws open the door, and we see the bride. But first a bit of commentary.

He’s without a home, remember, because he’s hiding from the secret police. Naoko is an outsider because she’s tubercular. Jiro is an outside because he’s wanted by the secret police – though he continues in his job of designing warplanes for the Japanese empire. The Kurokawas, by harboring him, are complicit in whatever it is that he’s done. Remember, when Mr. Kurokawa originally decided to take Horikoshi in, that he told him some friends had been taken by the secret police without any word as to why. These are citizens living in fear of the state that they also serve. This is not a comfortable world Miyazaki is presenting to us, true love not withstanding.

01:44:51

The bride: Notice those white flecks. What are they? Snow flakes? Indoors? Is Miyazaki eliding the difference between the outdoors where it’s snowing and indoors where a wedding is about to take place?

01:45:01

Horikoshi: “You’re beautiful.”

01:45:09

They share a drink. Water? Tea? Sake?

01:45:27

Naoko: “Mr. Kurokawa, Mrs. Kurakawa, all Jiro and I have in this world is each other. I cannot thank you enough for your kindness. We will never forget our debt to you.”Mrs. Kurokawa: “Nonsense, there is absolutely no debt to repay. We’re both so happy that you found each other. Aren’t we, dear?”Mr. Kurokawa [bowing]: “Um huh! You’re both very very brave.” They’re both teared up.

And Miyazaki cuts to a shot of the moon.

Again, I don’t know how to read this against contemporary Japanese culture. But let’s not belabor the point. Does it really matter whether or not Miyazaki is making a point about what life was like back then (the early 1930s) or about life now? It was so long ago, and yet not so long. And this is art.

Wedding Night

They retire for the night, and Horikoshi prepares to sleep on a separate futon, next to his wife’s.

01:46:24

Jiro: “You must be exhausted.”Naoko: “I feel like I’m in a wonderful dream. It feels like the room in spinning.”Jiro: “You should try to get some rest.”

01:46:35

Naoko: “Come here”Jiro: “Are you sure?”[She rolls down the blanket.]Naoko: “Come here.”

01:46:40

He stands up, turns out the light, the screen fades to black as he’s getting into bed with her, and we’re left wondering what happened. But is there any doubt about what she wanted when she uttered that second “come here”, or that he was eager to do so, despite his concern for her health?

Miyazaki cuts the to daylight – a bit later, but there’s no specification – when Horikoshi is visited by his sister, who is waiting when he comes home. He’d forgotten she was coming; she’s angry; he congratulates her on becoming a doctor; she’s now met Naoko. And she upbraids him for spending so much time at work and thus leaving her home alone all day: “Did you know she puts rouge on her cheeks so you won’t worry? Naoko’s condition is much worse than you think, Jiro” (c. 01:47:59).

They finish talking and he goes in to Naoko, who awakens as he enters the room. They chat as he puts on his bedclothes while she hangs up his clothes. He finishes his design that night, working next to the bed while holding Naoko’s hand (c. 01:49:58):

Naoko: “This is nice. I really like looking at you while you’re working, Jiro.”Jiro: “In a contest for one-handed slide-rule users, I’d win first prize for sure.”

He completes the design. It’s for the A5M, which will test out successfully in a few days. And it’s at that point, the test flight, where Jiro’s actions once more intersect with those of the imperialist state.

Note his mention of his slide-rule, which has been a motif throughout the film. When he first met Naoko he used his slide rule as a splint for her nurse’s broken leg. It’s returned a couple of years later and we see him use his slide rule in several scenes.

* * * * *

I’ll say more about this marriage in a later post, perhaps the next one. Right now I just want to emphasize the ways in which Miyazaki has staged this marriage as taking place at the margins of society. Noako is tubercular and may not live much longer and Jiro is in hiding from the secret police, even though he’s working on the design of a plane for the Japanese military. We normally think of marriage as binding individuals more deeply into society. In The Wind Rises, this marriage has almost the opposite effect, that of creating an imaginary boundary around Naoko and Jiro that keeps them separate from society.

Recall, furthermore, that Jiro told Mr. Kurokawa he’d leave with Naoko if he had to and abandon his work on the A5M. At the same time we saw that he courted Noako with paper airplanes and that one of them had roughly the form taken by the A5M [3]. Miyazaki’s playing a delicate balancing game here. What’s in the balance: Horikoshi himself.

References

[1] Marriage in Japan. Japanreference. March 4, 2013. Accessed November 30, 2015, URL: http://www.jref.com/articles/marriage-in-japan.223/

[2] Gilles Poitras' website: Service to Fans. URL: http://www.koyagi.com

[3] See my post, From Concept to First Flight: The A5M Fighter in Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, URL: http://new-savanna.blogspot.com/2015/11/from-concept-to-first-flight-a5m.html

This subject is detailed and nuanced, and such a part of the Japanese culture for so long that Miyazaki didn't have to parse it in such depth. For those of us on the outside, however, there are some things we need to know.

ReplyDeleteThe current Japanese system of solemnizing marriages was put into place in 1635, during the early Tokugawa, under the name "terauke-seido". It had the effect of bringing Buddhist temples into the bureaucracy of the state by making them responsible for recording the creation of new families. THAT is marriage in Japan; everything else is pretty much cosplay, for the sake of the families and/or the bride and groom. I researched this as part of a look at the popularity of "white" Christian weddings in a country where Christianity is a profoundly minority religion.

As for the police state aspect of Japan before and during WW2, we see bits of this in "Millennium Actress" also. It alludes to the Peace Preservation Act of 1925, in which anyone who does anything offensive to the "kokutai" (basically, the well-being of the state) could be dragged in for questioning or imprisonment--trial optional. The Act was amended in 1928 to include the death penalty; hence the unspoken necessity to hide the dissident artist. His art had severe consequences. For another perspective on the Act I recommend Mikiso Hane's excellent book "Reflections on the Way to the Gallows".

Thanks, Patrick. Marriage as family alliance, of course, was once the norm in the West as well. It was the norm in Shakespeare's time; that's the background against which Romeo and Juliet played. It didn't disappear in a sharp fashion; these things never do. But it was in eclipse by the time Jane Austen was writing. And she was writing a half-century before Perry landed in Japan.

ReplyDeleteHave you watched the 1954 Gojira? There's a romance plot that centers on a conflict between arranged marriage and romantic marriage and it's quite important in the film. That must have been a very real issue in Japan in 1954, while it would have had almost no meaning in America. The Americanized version of the film – Godzilla, King of the Monsters (1956) – all but eliminated it. What I have no sense of is how real the issue remains in contemporary Japan. It certainly lingers on in anime and manga.

O good stuff. And your mention of boundaries I think is perceptive--boundaries are a key theme in this film.

ReplyDeleteYes, boundaries all over the place, not the least between one scene and another.

Delete