I’ve mentioned the film’s title in other posts, but Miyazaki is so insistent on it that I decided it required a post of its own. But not entirely its own. I want to juxtapose the rising wind with another motif that is prominent in the film, design and mechanical detail.

The Rising Wind

Miyazaki tells us about his title as soon as the film starts. Immediately after a shot of the title he tells us where it came from:

00:00:33

The Japanese version, of course, has a translation into Japanese. Immediately after the film ends, and before he runs the end credits, Miyazaki has a shot telling us that the film is “A Tribute to Jiro Horikoshi and Tatsuo Hori”. It is in Hori’s novel, The Wind has Risen (風立ちぬ – Kaze Tachinu), that Miyazaki got the story of a woman with tuberculosis on which he based his fictional account of the real Horikoshi’s wife.

But, as we’ve already seen in How Caproni is Staged in The Wind Rises, Miyazaki repeats the title in the film itself, both literally, and in imagery. It enters the film during the Kanto Earthquake sequence, which starts with Horikoshi on the train back to Tokyo. Young Naoko Satomi utters it as she notices the wind – Le vent se lève. At the same time, a gust carries Horikoshi’s hat away

00:14:24

and she manages to catch it, though she almost falls from the train herself.

00:14:25

They then have a conversation in which she repeats the opening of the line – Le vent se lève – and Horikoshi completes it: il faut tenter de vivre. A few minutes later, after the earthquake has struck and after Horikoshi has made his way to his college after helping Naoko and her maid, Caproni repeats the whole line as he scraps the film of the failed flight of his dream plane.

In this one sequence, then, Miyazaki has 1) staged the first meeting between his protagonist and his future wife, 2) linked the film’s title phrase both to that meeting and to, 3) his protagonist’s virtual mentor, Caproni, and done it all 4) in the context of disaster, the earthquake and the failed flight. He has done this both verbally and in the events he depicts. Nor is not only the gust of wind that takes Horikoshi’s hat, but also the winds that fan the flames in Tokyo – in the course of which, incidentally, Caproni asked Horikoshi whether or not the wind was still rising.

The thing about the wind is that, when it blows, it is both pervasive and elusive. Given that we might ask just what the phrase means for Miyazaki and the film. It might be better to ask: How does Miyazaki use it? What does it do?

Horikoshi’s second meeting with Satomi is also mediated by the wind. This time we’re not on the way to an earthquake, though. We’re at a mountain resort where Horikioshi is on hiatus after a failure at work, his first as chief engineer on a project. Satomi is up on a hill at work on a painting, though we don’t yet know that it is her

01:05:43

and the wind carries her umbrella away.

01:05:48

Horikoshi manages to catch it and wrestle it to the ground.

01:06:01

Her father, who is out walking as well, retrieves it from Horikoshi and returns it to her. It is only a bit later that we learn just who she was.

But surely we suspected that at this point, no? (I don’t actually remember my own response.) Between the conventions of such films and the pains Miyazaki has taken to associate her with the wind, how can we not think that this must be that same person, now grown to adulthood?

Satomi then returns at the very end of the film, where Horikoshi has been chatting with Caproni in the liminal meadow where they’ve met before. Horikoshi sees her walking toward him:

02:01:49

Then, after a brief, life-affirming, interchange she floats up and dissolves into the wind.

02:02:19

Caproni: “She was beautiful, like the wind.”Horikoshi: “Thank you, thank you.”

We might think of the illness that killed her, tuberculosis, as an illness of the wind, as it affected her ability to breath. And more generally we have the association between airplanes and the wind.

Design and Mechanism

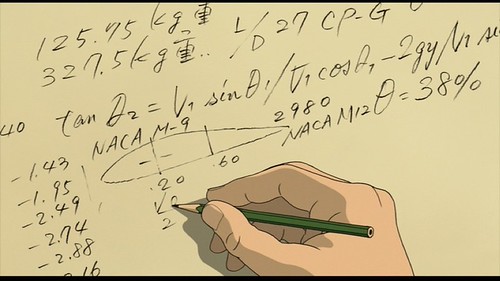

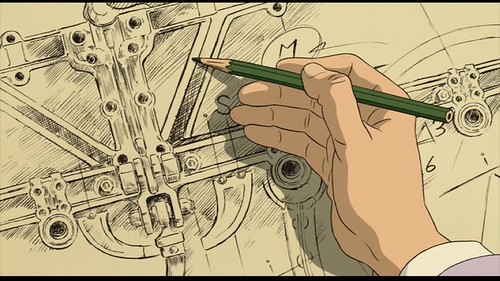

The other thematic element is quite different. I’m thinking of how Miyazaki emphasizes design and mechanism. Horikoshi, of course, designs airplanes. So Miyazaki frequently shows him with the tools of his trade, paper and pencil. We saw that when Horikoshi first took his job with Mitsubishi, which I discussed in Horikoshi at Work: Miyazaki at Play Among the Modes of Being. Thus we saw him making calculations:

00.34.38

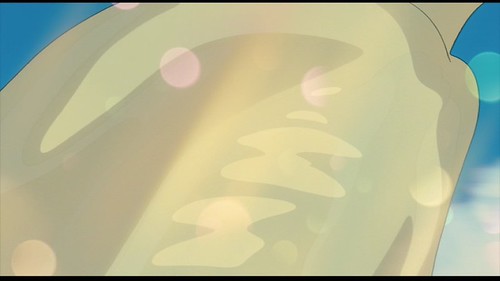

Later in that scene we see internal details of wing structure as air flows over it. Is Horikoshi imagining this in just this way or is Miyazaki simply showing us how things work independently of the exact specifications of Horikoshi’s imagination?

00.34.57

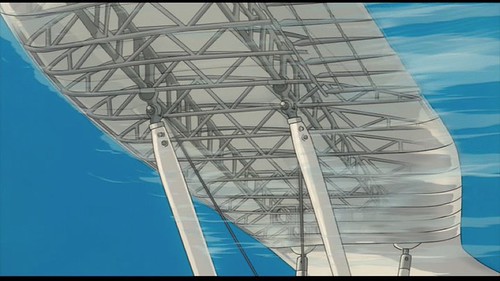

Still later in that sequence Jiro and Honjo go for lunch. Afterward they visit the assembly shop where they inspect the strut mechanism:

00:36:08

Back at the office we again see Horikoshi at his drafting table:

00:36:21

He seems to draw quickly and well.

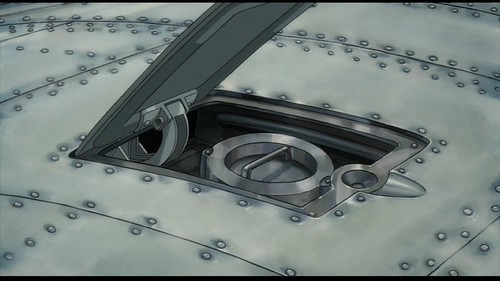

Later in the film, just before he goes into hiding from the secret police, Jiro shows Honjo the plans he’s just drawn up for some fittings on the surface of the plane. As he explains the idea we see an animation depicting the idea in action:

01:26:47

That’s a cover for the fuel port. In Miyazaki’s animation it opens and closes on its own. In actuality, of course, a person would be opening and closing it.

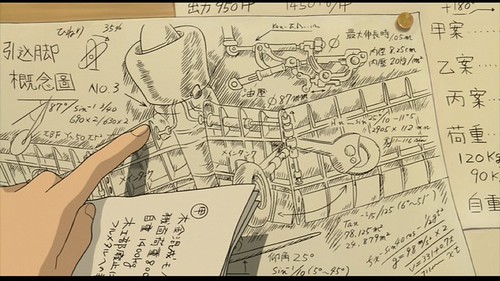

Here’s another drawing, which Horikoshi is presenting during a design review:

01:36:21

The film also has shots of the engineers at work. Here’s one of them:

01:40:03

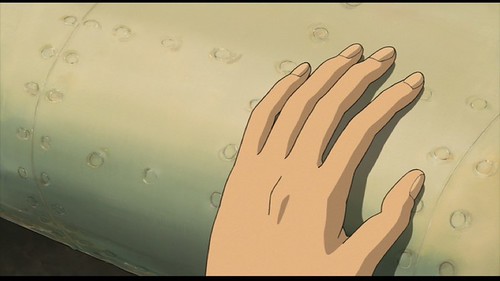

And here Honjo is looking at, and touching, another of Horikoshi’s ideas, flush rivets to reduce drag:

01:51:24

Whatever Miyazaki is doing, he wants us to see engineering design in action. We see the engineers at work at their drafting tables and we see those designs translated into physical structures. At a small scale we have these shots of component parts. At a large scale, of course, we see the planes in flight. Engineering is not simply what Horikoshi does, it is also one of the things The Wind Rises is about. It is thematically central to the film.

Dialectical Interplay

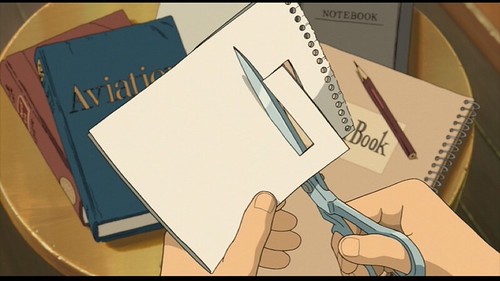

These two themes interact in Jiro’s courtship of Naoko. Here we see him cutting paper for a paper airplane (notice the books on the table):

01.18.57

We have design and fabrication in one action. Once fabricated he tosses the plane: “Let the wind carry these wings, carry these wings to you.” And the wind does that, though not directly.

01:20:27

She retrieves it, throws it back. Things happen. It’s complicated. Another paper plane. And so forth. The point is simply that this scene combines these two themes, the capricious wind and the designed plane. The upshot of this scene is that the two are in love. A bit later Horikoshi will ask her father for her hand in marriage and she’ll accept.

We might, as analysts and critics, ask just what Miyazaki is doing, philosophically, with these two themes. The wind is a natural force and acts capriciously, by chance, at least from a human point of view. We can neither predict nor dictate what the wind does. Design, in contrast, is something we humans can do. It is through design that we shape and control the world.

The wind brought about two meetings between Jiro and Naoko; but it was through design and deliberation that they became a couple. It is not merely that Jiro designed a fabricated two paper airplanes and that the wind bore them aloft. Those are the devices through which Jiro and Naoko could play with one another.

Where is play in Miyazaki’s metaphysics?

* * * * *

An exercise for the reader: Take the thought in those last paragraphs and develop it into a specific and explicit argument, something that might in fact be termed a philosophical stance.

No comments:

Post a Comment