In Dumbo as Myth 1: Beginning and End I concentrated on the very beginning and the very end of the film, noticing that the end was the opposite of the beginning in mode of presentation. The story begins during a storm and asserts the difference between the sky and the ground. Birds live in the sky while other animals live on the ground. The story ends during the day and focuses on crows, creatures of the sky, sitting atop a telephone pole, which is sunk into the ground.

Now let’s take a look at the terms in which Dumbo takes his success and ask, once again: Why?

Success

Dumbo’s success comes, of course, during a circus act featuring him. He failed the first time, when he tripped on his ears and collapsed the elephant pyramid rather than landing triumphantly on top. He succeeded the second time, but was humiliated because he was made-up as a clown and was soaked in white goo. The third time, as the cliché has it, was a charm. He flew.

And in the Big City, which is important. The film started in winter quarters somewhere in South Florida and played in a few small towns. But Dumbo triumphs in the Big City where, of course, the clowns had been anticipating their own triumph.

Once Dumbo had dunked the clowns and shown off his flying skills he took mild revenge on those matrons who had spurned him an his mother, spraying them with peanuts as though his trunk were a machine gun:

That’s the last thing we see in his act. Of course, it wasn’t planned. Then we see him flying with Timothy Mouse in his hat proclaiming: “You’re makin’ history!”

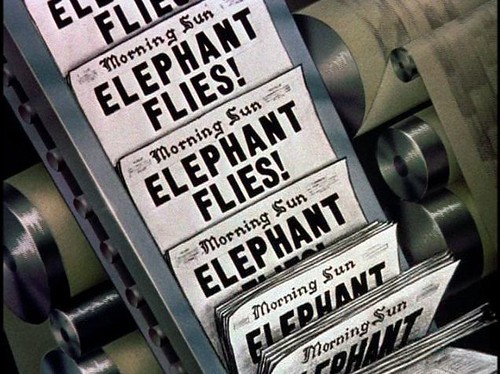

And the next thing we see is the presses rolling:

There’s high tech for you, mid-20th-century style: newspapers just flowing off the presses. Then we see several headlines, including “Dumbombers for Defense!” And then we return to the train, in motion, where Dumbo is at last re-united with his mother.

While the story was effectively over once Dumbo had demonstrated that he could fly, this elaborate coda is nonetheless critical. For one thing it assures us that, yes, Dumbo really is reunited with his mother. That’s closure, as they call it these days. His separation from his mother was the event that drove the plot, and it wasn’t even his fault. He was separated from her because of what she did to protect him. Now he’s reunited with him, wearing his aviator’s cap and without Timothy Mouse.

This could easily have been accomplished without all the hoopla, without Making History. But the making of history WAS the point, though in Myth Logic, not in the ordinary logic of interpersonal (that is, inter-elephant) relationships. The fact that we see history made BEFORE we see the happy reunion puts the making of history WITHIN the mythological scope of the reunion plot.

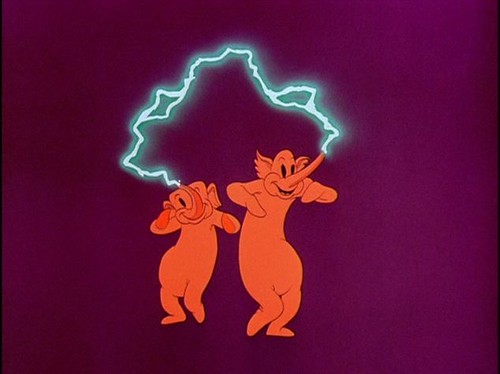

That means that the equivalence between Dumbo the flying elephant and those high-tech bombers is no mere decorative accident. The point is not so much that the high-tech was military—though that was obviously salient in 1940 when Dumbo premiered and when the European war would have been on people’s minds—but simply that it WAS high tech. Disney prepared us for this equation with Pink Elephants on Parade, when two elephants became juiced (on electricity, that is), reproduced, and then morphed into cars and trains.

And even earlier than that, even earlier. Way back in the beginning, when the movie went from the chaos of the opening storm to the calm moonlit night with the storks, during that transition the sound-track had the sound of some kind of engine zooming by. That’s the same sound we heard when Dumbo pulled out his dive in his final act, just before he would have gone into the white goo (as the clowns had planned).

Dumbo, this big-eared oddball elephant was Disney’s vehicle for assimilating Big City High Tech ways to the small town intimacy of the circus. In Myth Logic.

Winter Quarters

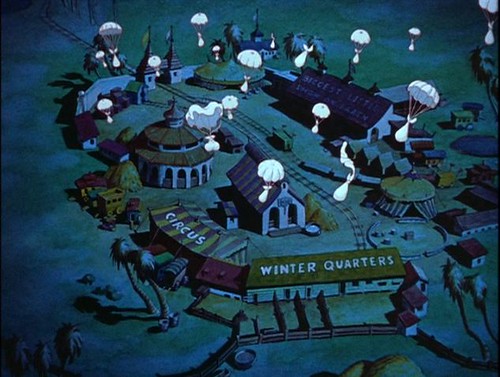

Let’s go back to the beginning and continue on to see how Disney sets things up. We’re following those original storks, the ones we saw immediately after we left the storm (to the sound of an airplane engine). Those storks do not land; rather they descend a bit and drop their bundles into the winters quarters of the circus. We know it’s the winter quarters because that’s what the label on the roof says:

The bundles are now slung beneath parachutes and they’re dropping into what appear to be permanent dwellings for the animals rather than tents or railroad cars.

And, as we can see, this happens at night. But there’s no bundle for Mrs. Jumbo, though she scans the sky for one. But there is, alas, no bundle for her:

Why not? The question I’m asking is about myth-logic, which is different from the questions we presume Mrs. Jumbo to be asking. Why didn’t Disney have Dumbo delivered at the same time as the others? Perhaps it’s a matter of drama craft. He wanted to create expectation and suspension. That accounts for the delay, but not for many other things.

Dumbo is Different, Why?

It’s not simply that Dumbo himself is different from other elephants because his ears are so large. Rather, the circumstances of his arrival are different, and in ways that cannot be explained simply by the desire to create suspense.

That alone does not explain these differences:

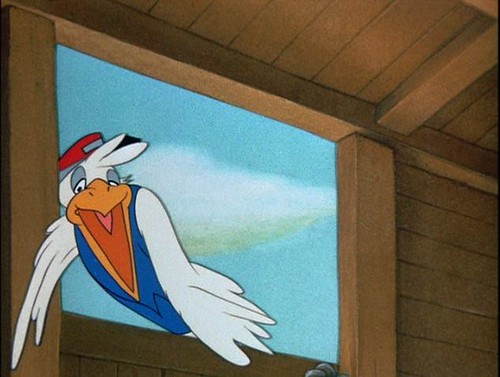

- The stork delivering Dumbo is not realistically rendered, like the other storks.

- The stork delivering Dumbo wears clothes and talks.

- The stork consults a map (suggesting he might have been lost?).

- The stork asks Mrs. Jumbo to sign a receipt.

- And then sings a naming song.

- And, Dumbo is delivered during the day and on the circus train while it’s in motion.

There’s more going on here than dramatic delay and a gag or two, such as having the stork snatched away by a mail hook at the very end of his song:

And it’s not as though we can’t see that Dumbo’s ears set him apart from other elephants. That is, Disney’s artists surely aren’t worried that we’ll miss those ears and so are piling on all sorts of differences so we’ll get the point.

The point isn’t simply about the ears. It’s also about all those other things too.

Let’s return to Lévi-Strauss, whom I mentioned in the previous myth post. He argues that myth is, above all, an attempt to draw a line between nature and culture and so between humans and animals. Something like that is going on here. I say “like” that because, of course, this story centers on animals, not on humans.

But there is a clear distinction between animals that wear clothes and animals that do not. The elephants wear clothes, caps and blankets, while, with one exception, the other circus animals do not. The exception is Timothy Mouse, who is Dumbo’s companion and protector. The crows wear clothes. And the stork who delivers Dumbo wears clothes, but the other storks do not.

Further, the animals that wear clothes also talk, with two exceptions. Dumbo never talks. One could, I suppose, attribute this to the fact that he’s an infant. That’s not very convincing, though, not in a cartoon where a locomotive going up a steep hill chugs out “I think I can I think I can” (this happens just before the tent raising sequence). Dumbo doesn’t talk. He’s got big ears and, in time, he flies. But talk he does not.

The other non-talking elephant is his mother. She speaks only once, to utter his name, Jumbo Jr., but otherwise she never says a word, though the other elephants chatter up a storm. She defends Dumbo physically, closing an opening against the other elephants as they insult her child, but she doesn’t speak in his defense. Nor does she speak to him when he visits her at night.

So, what I’m suggesting, then, is that all those differences attending Dumbo’s ‘birth’ are about something other than the fact that he also has big ears. We’re dealing with what Bruno Latour calls the collective, and about how the collective is constituted. By “the collective” Latour means society and when he talks of constituting society he means, not simply relations among people, but relations among all the beings that make up society, people, animals, plants, inanimate objects, the land, the sea, resources, bacteria, concepts, all of it. All of it must be gathered to constitute society.

[See Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, 1993; Politics of Nature, 2004; Reassembling the Social, 2005.]

That’s what Disney is doing. He’s reconstituting the collective so that it can accommodate a big-eared elephant and, oh by the way, all this high tech electricity stuff too. I’m going to leave the electricity to the next post. And I’m not going to say much more about technology in this post. But I do want to say something about work and home.

Tent Raising

On the second night we have the tent raising. Why make such a big deal of that? What does it have to do with the plot? Not a great deal that I can see. It shows Dumbo working hard to be useful, but other than that it doesn’t advance the story all that much. That is, if you think the story is just about Dumbo, his mother, and their travails.

But it’s about more than that, as I’ve asserted above. It’s about the circus as a microcosm of the world. To that end, Disney is willing to devote two and a half minutes of the film to establishing the circus as a place of work. That is, we see it as a place of work before we see it as a place of entertainment. Further, we see it primarily as a place of work, even during the sections where we’re watching that entertainment.

The tent raising is the first point in the film where we see humans. And the humans we see are faceless roustabouts. They work together with the elephants to erect the big top.

That’s what this is about: work. The circus may be recreation to the audience, but it is work both to the performers and to those who support the performers. The elephants play both roles. The provide the muscle power to raise the tent and they perform an act under the tent.

During the parade the following day we see that the animals are bored. The parade may be exciting to the townspeople, but the animals have done this before. It’s nothing special to them.

And the young boy teases Dumbo, he’s having fun; he’s taking recreation. When Mrs. Jumbo protects her son and punishes the boy, not only is she overstepping the line between humans and animals, but she’s also overstepping the line between work and play. She and Dumbo may not have been in the ring at that time, but they were nonetheless on display. They were at work, and their work is to provide entertainment for the humans.

The other elephants may have rejected Dumbo because he was an odd looking elephant. But that in itself was of no consequence to the humans who ran and who attended the circus. A freak is good entertainment, and that’s what he was, a freak. But if his mother won’t let him serve as a freak, won’t let him work, well then that’s a problem.

And so she’s locked up.

Once Dumbo discovers that he can fly, of course, why then he can return to work, if in a somewhat different capacity. Not only that, he provides a model for those bombers. More work.

Meanwhile...

This film is being made by people for whom entertainment is a business. The story of the circus is thus their story. They work so that others may be entertained. And Dumbo? Perhaps he’s a figure for animation in the context of the movie business at large. As for technology, Disney worked hard at being the most technologically advanced studio in the animation business and, more generally, in the movie business.

But that’s just an aside. There’s still a lot to work through. For example, what do we make of Timothy Mouse? He serves Dumbo in a way that Jiminy Cricket served Pinocchio. Pinocchio’s needs were different from Dumbo’s, so his diminutive is different. In both cases we have, in effect, one person who’s been divided into two components, one that’s growing and one that’s guiding.

If Timothy Mouse is, then, just one aspect of a being for whom Dumbo is the other aspect, what do we make of the fact that it’s Timothy Mouse who concocts the act that brings about Dumbo’s downfall?

Whoops!

At the same time, thinking of Timothy Mouse as an aspect of Dumbo solves a problem. Remember when we noticed that there are two kinds of animals in this story, those with clothes and those without? At that same time we observed that the animals with clothes also talked, with two exceptions: Dumbo and his mother. If Timothy Mouse and Dumbo are, however, two aspects of the same being, then that solves our problem. Timothy Mouse is the voice of Dumbo.

And he’s also the voice of Mrs. Jumbo. In the his first scene he decides to scold the elephant matrons for the way they’ve shunned Dumbo. He is, in effect, speaking on behalf of Mrs. Jumbo, defending her son against the matrons as she’d earlier defended him against the boy.

And yet he’s also the source of the idea that fails so badly that, far from making Dumbo a star, it gets him banished from elephantdom.

Oh my!

What a mess. This calls for extreme measures.

Like morphing pink elephants.

And jive-talking crows.

Next time.

No comments:

Post a Comment