One of the most profound books I’ve ever read was written by William Powers: Behavior: The Control of Perception (1973). It received a positive review in Science, which is how my teacher, the late David Hays, learned about. He urged his students to read it and it became foundational to our thinking. In particular, when it came time to reconceptualize the cognitive model Hays had been developing over the years, he adopted Powers’s system as a model for the sensorimotor component of the system.

I don’t have time to go into Powers’s model in any detail. Suffice it to say that it was based on servomechanical control systems or the sort that Norbert Wiener popularized, at least in intellectual circles, in his Cybernetics. Powers’s innovation was to imagine a simple and elegant scheme whereby control systems were stacked one above the other, with higher level systems regulating the activities of lower level systems and lower level systems providing inputs to, and realizing outputs from, those same higher level systems.

In this note I’m interested in what Powers has to say about conflict. Here’s how he sets it up (pp. 253-254):

A person is said to be “in conflict” when he wants two incompatible goals to be realized at once. Since the time of Freud and no doubt for much longer than that, inner conflicts have been recognized as a major cause of psychological difficulties. Unresolved conflict leads to anxiety, depression, hostility, unrealistic fantasies, and even delusions and hallucinations. In fact as I have come to realize what inner conflict means in terms of this feedback model, I have become more and more convinced that conflict itself, not any particular kind of conflict, represents the most serious kind of malfunction of the brain short of physical damage, and the most common even among “normal” people.The reasons for the extraordinarily bad consequences of conflict are not to be found in specific behavioral efforts, although disruption of overt behavior certainly can make life difficult. Our model, however, tells us that mere practical consequences of specific conflicts are secondary to their major consequence, which is to remove parts of the brain’s organizations from action as effectively as if they had been cut out with a knife, yet without getting rid of their undesirable influences on the whole hierarchy [of control systems]. The worst aspect of conflict between control systems is that the higher the quality of the control system, the more violent and disabling is the result of conflict.

A bit later, p. 254:

Conflict is an encounter between two control systems, an encounter of a specific kind. In effect, the two control systems attempt to control the same quantity, but with respect to two different reference levels. For one system to correct its error, the other system must experience error. There is no way for both systems to experience zero error at the same time. Therefore the outputs of the systems must act on the shared controlled quantity in opposite directions.

Immediately before this paragraph Powers had observed that “when two people arrive simultaneously at opposite sides of a swinging door they do not simply stop as two rocks rolling against each other would.” Let’s play that situation out as commentary I’d just quoted in full, with commentary in italics:

... the two control systems attempt to control the same quantity, but with respect to two different reference levels.The position of the door is the controlled quantity.For one system to correct its error, the other system must experience error.That is, when one person starts to on push the door, the other will see the door moving in what he or she regards as the wrong direction and will push back.There is no way for both systems to experience zero error at the same time. Therefore the outputs of the systems must act on the shared controlled quantity in opposite directions.The two will simply try harder and harder to move the door in the direction each favors. If they are matched in strength, neither can possibly win. But they might will injure themselves.

Let’s consider a different example, one I’d used in my dissertation, Cognitive Science and Literary Theory (1978). The example is artificial, but it gets the point across. Harry, John, and Frank are playing the children’s game “hot and cold.” As you may recall, the game is played with respect to a goal. One player is blindfolded and moves about the play space. As he gets closer to the goal the other players so indicate by telling him that he’s getting warmer or, when very close, even hot. If he moves away he’s said to be getting colder.

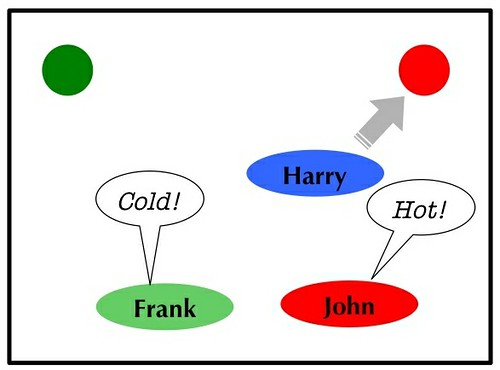

In this game Harry is blindfolded. But there’s a peculiarity. There are two goals, a red ball and a green one. John is trying to direct Harry toward the red ball while Frank is trying to direct him toward the green one. The two balls are at opposite sides of the game space. Here we see Harry approaching the red ball:

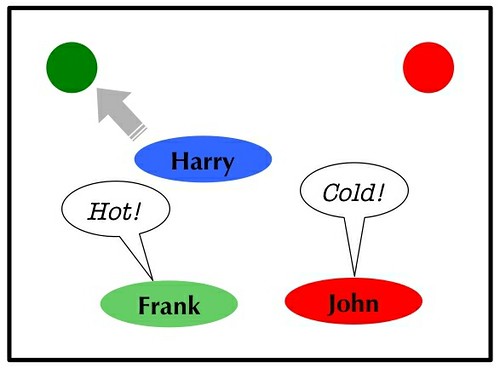

Here he’s approaching the green ball:

As long as Harry can distinguish between the two voices he’s OK. He just picks one voice and listens to it while ignoring the other. If he listens to Frank he’ll end up at the green ball and if he listens to John he’ll end up at the red ball.

But what if he can’t tell the voices apart? He hears both, and at any given moment he can hear one yelling “warmer” while the other is yelling “colder.” But he can’t track the continuity of each voice from one utterance to the next. If in the course of wandering around Harry should reverse his direction of motion with respect to the two goals, John and Frank will reverse what they’re saying, but Harry won’t hear the reversal because he can’t tell one voice from the other.

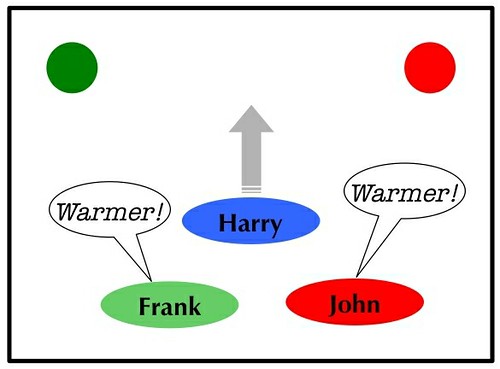

And what happens in this situation:

Harry is equidistant between the two balls and is heading right between them. Both John and Frank will be telling him he’s getting warmer until he crosses the line between the two balls, at which point they’ll both tell him he’s getting colder.

This conflict has made it impossible for him to reach either goal, much less achieve both. That conflict has effectively taken Harry out of action.

THAT’s why conflict is so debilitating.

No comments:

Post a Comment