This post is about the opening dream sequence of The Wind Rises. I’m interested in the way this sequence prefigures the whole film. The sequence is about four minutes long, four minutes in which nothing happens to advance the plot. It “sets the scene” and establishes a mood. That’s all.

This is Miyazaki’s only feature-length film since his first, The Castle of Cagliostro, that does not have strong supernatural aspects. They’re very prominent in some films – Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle – and not so prominent in others – Kiki’s Delivery Service, Porco Rosso – but they don’t exist in this one. Dreams, yes, but that’s different. THAT is in itself an important feature of The Wind Rises.

The film has a minimal title sequence. We see the title in plain letters (kanji characters in the Japanese) on a blue-grey screen and simultaneously hear a mandolin accompanied by a guitar. The music is wistful and nostalgic. If you’re familiar with Miyazaki’s work you may think Porco Rosso at this point, as much of that film took place in Italy.

There will be no speaking at all in this sequence. Later dream sequences will have conversation.

That screen gives way to one where we see the quote from Valéry that gives the film its title: “The wind is rising! We must try to live” (in French and Japanese in the Japanese version). When that leaves the screen we see something like this, with the mandolin and guitar continuing accompanied by a concertina or accordion (one of those, I can’t really tell):

00.00.54

Notice the numbers at the lower left of the frame grab; that’s the timing in hours, minutes, and seconds. The timing starts at the beginning of the DVD, not of the film proper. Subtract 24 seconds or so to get the time from the beginning of the film.

This is not quite the first thing we see – I really can’t frame grab everything. The first thing we see is waving grass beneath the fog. Then we see this house rising out of the mist.

We move in closer. Is that a small shrine at the left? Notice the shape of the branch impinging from the left, like you see in traditional Chinese or Japanese paintings.

00.01.00

We zoom into the house where we see two children sleeping under mosquito netting. Jiro Hirokoshi is the one in the center; he’s the protagonist. That’s his sister to the left. She plays no role in the dream, but she’s a secondary character in the film. She’ll become a physician.

00.01.02

The (virtual) camera zooms in on Jiro:

00.01.09

And then we cut to a shot of him climbing along the roof of the house. What fun.

00.01.21

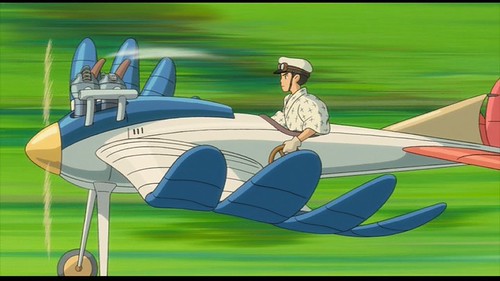

He walks along the roof ridge toward this slightly odd looking airplane. Can it fly or is it just an elaborate ornament as we sometimes see on Japanese houses and castles?

00.01.31

Jiro climbs into the cockpit and acts like the thing is going to fly. This next shot, from down in the cockpit looking up an out at our pilot, is straight out of Porco Rosso, as anyone who’s seen the film will recognize.

00.02.01

Porco Rosso in his cockpit

If you HAVE seen the film, what does that tell you? Is this recognition essential to the film? Of course not. But if you, as a critic, want to figure out what’s going on in Miyazaki’s films, establishing alignments between them is a useful part of the process.

Now we see young Jiro in full flight while the sun rises over a mountain. (When he awakens it will be morning.) Is this real or a dream? At no point in the sequence did Miyazaki signal that we’ve entered a dream. At the beginning we saw a shot of a sleeping boy and then we cut to a shot of that boy climbing the roof of the house. We’re given no information whatever about what happened, what boundaries were crossed, in that cut. There’s no reason to think that the boy climbing the roof was doing so in a dream. Boys do in fact climb roofs – I did it myself, often.

00.02.08

But then when we see him walk along the roof ridge toward a small bird-like plane, then we might wonder what’s going on. That’s not a real plane, is it? Or maybe it’s real in this movie, which after all IS a cartoon even if it’s loosely based on a real life (and how much do we really know about that life when we watch the film?). So these questions arise, not so explicitly, and you can’t follow them out because the film is moving along in real time and you have to follow it and now see! he’s climbing into the cockpit and taking off. Isn’t it glorious?

Yes.

But is it real or a dream?

I forget just what I was thinking at this point in the film. More likely than not I was hovering somewhere between real and dream. Have you ever heard of fuzzy logic? No, I don’t mean incompetent thinking. I mean a mathematical discipline for reasoning about varying degrees of truth. It does away with binaries, like T or F, dream or real, and replaces them with...Well, that depends and we need not go into details here.

00.02.16

Let’s agree that at this point in the film I was allowing reality to float and was mostly enjoying the beauty of Jiro’s flight while noticing that I’ve seen this before in other Miyazaki films, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Castle in the Sky, and of course Porco Rosso.

Marco Pagot, the protagonist of Porco Rosso, was a superb pilot and a loner who made his living as a bounty hunter in the Adriatic between the two world wars. The film picks him up in middle age, where he somehow assumed a pig’s head (hence his nickname, Porco Rosso, the Red Pig) as a consequence of losing his best friend in battle in World War I, but we get flashbacks to his early youth. The next shot could easily be young Marco, except that he flew a somewhat larger triplane, not a small futuristic (for 1918, yes, this is a futuristic design) plane with bird-like pinions on its wingtips.

00.02.26

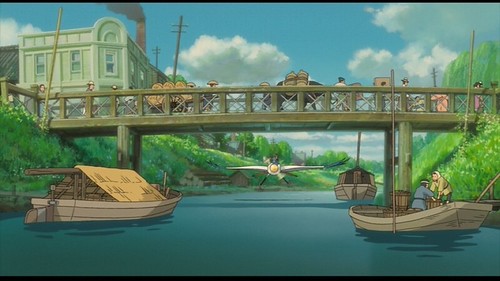

Here’s another shot out of Porco Rosso. Marco had lost a dogfight and took the remains of his plane to Milan for rebuilding. The shop was located along a canal. So, when Marco’s plane, a seaplane, was ready, they pushed it into the canal and he took off, flying along several canals and at one point going under a bridge, like this:

00.02.46

Marco didn’t showboat for his fans (his exploits were well known) on that particular flight as he was intent on just getting airborne and out of the city while evading the Italian air force; but he did played to the gallery earlier in the film. On that occasion his fans waved to him

00.02.58

And he waved back.

00.03.00

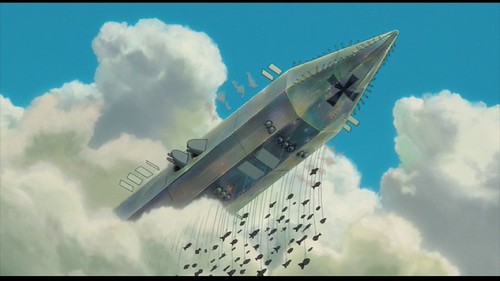

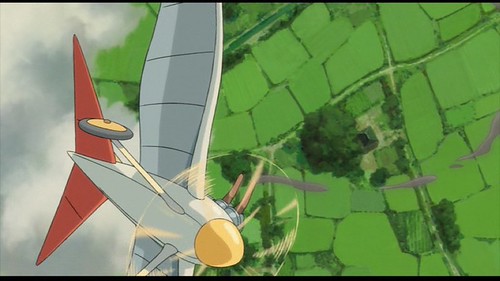

Note, however, that The Wind Rises is not about a pilot, as Porco Rosso was. Jiro Horikoshi was an aeronautical engineer. This is the first and last time we see Jiro piloting a plane. And yes, let’s get real, and admit that this has to be a dream sequence. And the dream turns ominous. The sound track music stops at this point and is replaced by an ominous hum. There will be no music from here through the end of the dream (and some way beyond, not until midway through the second dream sequence). Jiro looks up and sees the clouds dotted with dark things moving in formation. And then we see that they’re suspended from a huge dirigible marked with the Iron Cross – a premonition of war to come?:

00.03.21

Notice that many of these suspended devices are biomorphic, as Jiro’s plane is. Those dark creatures standing atop these things look like creatures from Howl’s Moving Castle, a film about a man-bird-wizard in a world haunted by war.

00.03.23

Jiro looks worried and moves his flight goggles into place over his eyes:

00.03.25

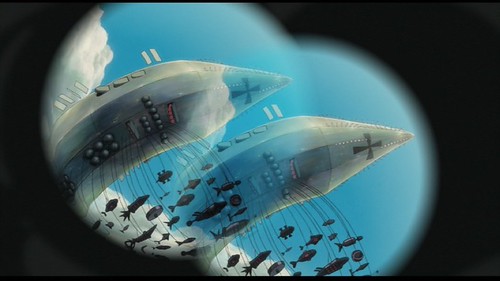

And now something strange happens. We assume Jiro’s point of view looking up at the war dirigible. He’s moving his goggles around (we see them move) and he’s having focus and registration problems:

00.03.21

Jiro’s plane spins out of control:

00.03.35

But what was that business with the wonky vision – and a bit of woozy sound accompanying it?

A bit of the flim-flammery that is the stock in trade for great artists. To see what’s going on we have to look very closely. More closely than I looked when I first watched the film and then when I watched the sequence again, this time taking screen shots. I didn’t consciously notice the following frames until just a few minutes ago when, in the process of writing these notes, I decided to go back to the film and do a bit of single-frame stepping.

Here’s what I saw. Distressed that his plan was spinning out of control Jiro rips off his aviation goggles – as though that would have any effect on gravity, inertia, and air flow. Look closely at the eye region of his face as the goggles come off:

00:03:37

Now that they’re fully off, look again:

00:03:37

Where did those glasses come from? Jiro wasn’t wearing them when he climbed the roof, nor when he entered the plane and began flying it. But now, after this warship appeared above him, after something went freaky with his vision, after he ripped off his aviation glasses, now he’s wearing glasses.

Scroll back up to the top of this post and look at the third frame grab, the one where we see the two children sleeping under the mosquito netting. Look to the upper right of Jiro. You’ll see his clothes neatly piled and his glasses are on top of the pile. He had the glasses all along.

This young boy wears glasses, as many young boys do. But not in his dreams. Or, in this case, not when he entered the dream. Then something happens. What’s the connection between those war machines and wearing glasses?

In the film’s second dream sequence (only a few minutes later) Jiro will enter the dream wearing his glasses. There he will meet Gianni Caproni, a famous Italian aeronautical engineer. Caproni will tell him that this is his dream too and then take young Jiro on a tour of a plane he’ll build when the war (the first World War) is over. At the end of that tour Jiro will point out that, because of his eyesight, he cannot be a pilot. But could he design airplanes? Caproni: “Of course!” And Jiro awakens from that dream determined to become and aeronautical engineer.

Two dreams, and a young pilot becomes a young engineer. It’s all about the eyes, but also war. One might hypothesize that the appearance of that war dirigible – which, by the way, resonates back to Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind – is a manifestation of the young dreamer’s realization that his need for glasses precludes his becoming a pilot. That makes local sense. But one must remember that war, if never quite the center of the film, is woven throughout and that the film ends with Japan’s defeat in World War II. Horikoshi, reluctantly, contributed to the war effort by designing the deadly A6M Zero fighter. That too is implicit in this opening dream.

That is, at this point in the dream sequence Miyazaki has conjoined two things: 1) the merely personal concerns of a young boy, grounded in his defective vision, and 2) the global geopolitical events in which he will live his life. To those I would add a third: 3) Miyazaki is also calling attention to the fact that, after all, this IS a film, something we view through our eyes, something that is constituted though optical devices, like cameras (remember: Miyazaki is still working in traditional hand-drawn animation, where images are photographed by a camera). It is THIS film, RIGHT NOW, that is both an event in our lives and a ‘commentary’ on life in general. It is through this film that we are summoning up our life’s experience and ordering it so that IT, life, hangs together in aesthetic experience in a way that the mere living does not.

Finally, a remark about Porco Rosso before returning to this dream. Marco Paget’s head became pig-like as a consequence of his experience in war. There’s a connection there with the fact that Jiro Horikoshi cannot be a pilot because of his eyesight. But I’ll let my psychoanalytic colleagues to work out the details.

Back in the dream, we cut to a close-up of one of those biomorphic war devices populated by ominous black creatures:

00.03.40

It crashes into Jiro’s plane, destroying it utterly:

00.03.41

That’s one of Jiro’s gloves in the foreground. Jiro, of course, is wearing his glasses as he plummets to the ground. This cannot end well.

00.03.47

But of course all that happens is that Jiro wakes up. It was, after all, just a dream.

00.03.52

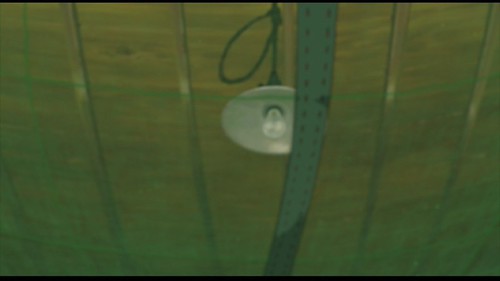

And he doesn’t seem particularly distressed by it. He looks up at the ceiling:

00.04.05

And then outside. Notice the shrine at the right. It’s the same shrine we saw at the beginning of the sequence (second frame above). Notice Jiro’s glasses atop his clothes:

00.04.12

He puts them on and now he can see clearly. He can even see the individual threads of the mosquito netting:

00.04.18

The camera zooms out beyond the netting:

00.04.27

It’s time to start the new day. And we’re about four minutes into the film (the timings include almost 20+ seconds of material before the brief title sequence begins).

* * * * *

Yet there’s a rather flat-footed sense in which those minutes have been wasted. After all, nothing happened. No action was initiated, much less advanced or completed.

All Miyazaki did was lay the ground for the rest of the film. If there is a connection between Jiro’s weak eyes and the fact that he became an engineer rather than a pilot, Miyazaki’s emphasis on those eyes and glasses, as we’ve seen, makes us aware of that that fact that he is, after all, telling this story in a visual medium. How can you not, when viewing those moments when Jiro struggles with his vision, how can you not be made aware of the fact that you are watching a movie with your eyes?

This dream is not real, but then neither is this film. The film, like all films, is something of a waking dream. How is it that these waking dreams help us to make sense of our lives. How is it that Jiro’s dreams – within this waking dream that is The Wind Rises – bring order to his life? How does Miyazaki use those dreams? And the way he uses them ¬– the ingoing boundary between reality – that is, everyday life in the film – and dream is always fluid. When the camera cuts from one scene to another you can never be sure whether or not you’ve entered a dream. You have to figure out where you are based on general knowledge of context and action. This is essential to Miyazaki’s style (in this film, but elsewhere too). Why?

So many questions.

* * * * *

Finally, a remark about method. As I remarked above, I didn’t realize the full extent of Miyazaki’s play with Jiro’s glasses until I began writing these notes. Oh sure, I caught the connection between eyes and film when I first watched the film. That’s easy. And I noticed and was puzzled by that bit about double-blurred vision just before the dream fell apart. But I hadn’t quite noticed that Jiro was wearing glasses when he fell from his plane. Maybe I knew that preconsiously even when I first watched the film. But it took the act of writing to force me into the sleuthing, frame-by-frame through less than a second of film, needed to explicitly register what Miyazaki had put on the screen.

Those details would have been obvious in the manga – Miyazaki told this story in a manga version before he made the film. I’ve not seen or read it but I assume that those details were there. If so, you couldn’t miss them.

I love this sequence. But it's not in the manga, which is different from the movie in several respects, and IIRC, doesn't deal with Jiro's childhood at all. You can find bootlegged torrent versions of it online if you look. Other short manga by Miyazaki have been translated and posted by fans, but I couldn't find a translated one when I was looking last winter.

ReplyDeleteInteresting. So Miyazaki's conception matured a bit. Thanks, Stephen.

Delete