How to Change Your Mind is a four episode miniseries on Netflix based on Michael Pollan’s book of the same name. It has four episodes, each named after a different psychedelic drug: LSD, Psilocybin, MDMA, Mescaline. I’ve watched the first episode. Color me underwhelmed.

Pollan serves as an on-screen guide and narrator, and is appropriately serious. He’s very clear that LSD is a potentially mind-changing and therefore very important drug. But, to be honest, he’s also a bit boring.

Before I get going, however, let me quote from a review of the episode published by James Hallifax in Psychedelic Spotlight News:

Episode 1 of Netflix’s How to Change Your Mind is a great introduction to the topic of LSD for those who don’t already know a lot about the subject. Narrated by Michael Pollan, the show takes us on a journey through the history of the powerful compound, from its discovery and its early medical use, to secret CIA mind-control studies, the counterculture and its banning, and finally to our current renaissance.

From amazing clips of LSD’s inventor Albert Hofmann describing his “Problem Child,” to powerful personal testimonies of individuals who have healed their suffering through LSD, episode 1 is a fun and entertaining refresher on the topic of LSD for even experts in the field.

In short, How to Change Your Mind’s first episode is definitely worth the watch.

My favorite segment came when psychedelic researcher James Fadiman was discussing an early LSD study on its effects on creativity, held at Stanford University in 1960. They recruited 48 senior scientists from various fields, all of whom had been working on a scientific problem to no avail for at least three months. In the study, each scientist was dosed with 100 micrograms of LSD, which can be considered a medium-sized dose.

As Fadiman describes it, “out of the people who came, we had 48 problems and 48 satisfactory solutions.” In other words, the LSD study was a stunning success. The fact that all 48 scientists —who had all been working on their problem for at least 3 months!!!— credited their LSD experience with solving their problem is nothing short of a miracle. True, perhaps this study would not meet the rigid rules of today’s clinical trials, but the results speak for themselves. According to Fadiman, “We had patents, we had publications, and because most of these people worked in industry, we also had products. And eventually the computer world emerged here.”

Despite this amazing story — and many more held within the one-hour premiere — the debut episode was not without its faults. Primary among them is its over-reliance on anecdotal stories, weaving a narrative that is not necessarily always backed up by current scientific study. The best example of this comes towards the end of the episode when Michael Pollan turns towards the subject of microdosing LSD.

About that last paragraph, I’m neither here nor there.

My problem with the episode is a bit different. It’s serious and, on the whole, dull. There’s some nifty special effects used to recreate the legendary bicycle ride taken by Albert Hoffman after he’d taken a substantial dose of LSD, 250 micrograms. There are some special effects scenes as well, and footage from some of Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests from the 1960s. But there was nothing like this:

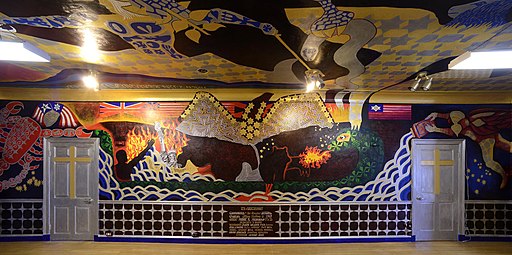

That’s a mural painted by Bob Hieronimus in Levering Hall on the campus of Johns Hopkins University in 1968-1969. I was a student at Johns Hopkins at the time; I saw that mural being painted. I listened to music played in that room, which functioned as a coffee house on the weekends. I rehearsed with a rock and roll band in a room next to that. That’s what I think of when I think about when I think about LSD.

Mind you, I am not now nor have I ever been an acid head. I’ve only taken LSD twice – which I’ll get to in a minute – but I was there and, if not exactly immersed in the culture, I spent a lot of time at its edges. I read a lot of the scientific literature on LSD and other psychedelics, not to mention a wide variety of material on mystical experience, I listed to the music, wore the clothes. And whatever THAT is, it’s missing from this episode.

The problem is one of technique, of aesthetics. How do you convey THAT while at the same time making it clear that you are not stoned out of your freaking mind? It’s clear that Pollan thinks psychedelics are important, that it’s important that we investigate them, and learn how to use them. He’s also aware that The Establishment, if you will, freaked out and made LSD illegal in 1968, shutting down all research on it. I mean, Pollan writes for The New York Times, fercrissakes, he IS the establishment (almost). He wants to steer clear of all that crazy stuff that freaks people out while at the same time knowing that, considered appropriately, the craziness is the point. It's not crazy, but rather reflects a different order in the universe.

As for my two acid trips, one was in January of 1972 and lasted approximately two weeks and the other was, I believe, in the Spring of 1974 and only lasted several hours. In neither case did I experience the visions and other sensory effects typical of LSD trips. Why, I don’t know. But that first one, that was a trip. Here’s a couple of paragraphs from an article I published in 1975:

What happens on an LSD trip is intimately bound up with one's expectations. I had lots of them. I expected to receive an insight (at least one!) into my study of language which would make it possible to write my masterwork. I had also expected to experience all kinds of nifty sensory effects. None of my expectations were met.

The sensory world remained the same and I spent two weeks living the life of a character in a Thomas Pynchon novel. I was on a quest and every event I faced was a test of my herohood. Nothing was what it appeared to be; everything had a hidden meaning. If I succeeded in my tasks the world would be saved and I would be inducted into the Secret Society of Master Creators (I didn't call it that at the time, but that is what it was) and spend the rest of my life as a Master of Improvisational Musics.

Winter in Baltimore is a dreary rainy affair. But those days in January were like the first days of spring–proof that I had succeeded and the world was being reborn. I received a letter from a friend which was misdated; the year read “1973” rather than “1972.” But I didn't think it was misdated; I merely assumed that self-sacrifice (as in Christ and Oedipus–sometimes I lay in bed at night pressing my palms into my eye sockets wondering if I would be called on to blind myself) had eliminated a year from time and that it was in fact 1973. (I didn't bother checking calendars.)

The account continues in that vein for a half-dozen more paragraphs and concludes:

Many of the people around me surely thought I was going mad. But none of this seemed in the least bit incoherent or confusing to me. And, as my cryptic messages went unanswered, as events refused to follow the course indicated by the signs, I realized that I had been acting out fantasies but that I had not broken free of them. My ego had been inflated, but not transcended. The dance had been exhilarating, but it lacked grace.

During that period I had signed up for trumpet lessons at the Peabody Institute and, as a result, brought my technique up a notch and have continued with the trumpet ever since. As important, perhaps more so, I completed my Master’s Thesis on “Kubla Khan,” and have been pursuing that work ever since. Would I have done those things if I hadn’t taken LSD? I don’t know. The fact is that before that trip I hadn’t played my trumpet in over a year and I was blocked on my thesis.

Pollan surely knows of that. It’s why he wrote the book and undertook this miniseries. I’ve not read the book, though I’ve read a review or two, but something is missing in this first episode. It tends to be strong on the facts, even if only anecdotally, and seems pitched at people who don’t know those facts. If you’ve lived through them, then there’s not much here for you. It jogs your memory, but leaves your imagination untouched.

I’m reminded of some lines from Coleridge’s “Dejection: An Ode”:

Yon crescent Moon, as fixed as if it grew

In its own cloudless, starless lake of blue;

I see them all so excellently fair

I see, not feel, how beautiful they are!

Where’s the feeling? Maybe things will improve in the other episodes. We’ll see.

Thanks for the review of the review, Bill. I saw the notice for the Pollan show last night and thought it might be interesting. A friend said someone she knows suffering from depression benefitted from LSD microdosing.

ReplyDeleteAnd thanks for the Hieronimous pictures. At first, I thought they might be something you did, remembering the wonderful painting you did on the Whitman's wall.

Forgot to say: I remember that 1972 LSD trip!

ReplyDeleteI figured you would, Frank. I still remember the room.

Delete