Wednesday, August 31, 2016

Description, Interpretation, and Explanation in the Case of Obama’s Eulogy for Clementa Pinckney

I want to continue the discussion in my previous two posts, Yet Another Brief for Description (and Form), and, Why Ethical Criticism? or: The Fate of Interpretation in an Age of Computation. I want to take a quick and dirty look at description, interpretation, and explanation with respect to Obama’s eulogy for Clementa Pinckney as I discussed it in “Form, Event, and Text in an Age of Computation” [1]. In that (draft) article I first present a (toy) model of the computational analysis of a literary text (Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129) and then discuss form, arguing for a computational conception. Then I take a look at Obama’s performance (which is readily available in video form) followed by a demonstration that the text is a ring-composition [2].

The ring-composition analysis is fundamentally descriptive. To be sure, I have to do some low-level interpretation to divide the text into sections. For example, I assert that in paragraph 17 the topic shifts from Rev. Pinckney and his relations to the nation and the black church’s role in it. How do I know that? Because that’s the first paragraph where the word nation occurs; then paragraph 18 talks of the role of the black church in the Civil Rights Movement. This sort of thing seems obvious enough.

But what’s there to explain? I can imagine that, in principle, the kind of computational model I created for the Shakespeare sonnet could be created for the eulogy. That might help us to explain just how the eulogy works in the mind. But I can’t see creating such a model now; we just don’t know how. That is to say, the eulogy’s ring-form design is something that needs to be explained by an underlying psychological model. And computation will be an aspect of the model.

What I don’t do is invoke the special terminology of some interpretive system: deconstruction, Lacanian analysis, Foucaultian genealogy, and so forth. I don’t offer a “reading” of the eulogy. I don’t, for example, offer remarks about the underlying theology, which seems to invoke the notion of the Fortunate Fall in its central presentation of the mysterious was of God’s grace.

* * * * *

Nor do I address an observation Glenn Loury made in conversation John McWhorter [3]. Loury is remarking on the fact that Obama took on the role of a black preacher and drew on the tropes and stylistic moves of black vernacular preading. They are remarking that, of course, this was a performance. But not an inauthentic one, though Obama was not himself raised in the black church. Loury says:

A mask, a face has to be made. A way of being has to be fashioned. It’s gotta’ be practiced. You could see him standing in front of the mirror. John, we should write the novel John. […]

It just resonates in my mind so deeply. Because what does it mean for a people, I speak now of black Americans 30-40 million, to have the embodiment of their generational hopes, personified by a person who must adopt artifice, and manufacture, in order to present himself as being of them. What does it say of such a people.No no no. I think this is historic profound. Excuse me if I, you know, I mean I’m just saying, here we are. Because think about it, think about it, OK, the stigma of race, slavery, OK, Orlando Patterson just brilliantly analyzes this, I think. Slavery has to be, you’re putting the slave down. The slave must be a dishonored person. OK so honor, honor becomes central to the whole quest for equality.And having the Chief Executive of State, be of you, or at the very least, be a person who when in a position of choice, chose to be of you, is countering the dishonor in a very deep way. But perhaps the only way that the state’s symbolic power could be married to your quest for honor is through the President of someone who wasn’t quite fully of you. Your stigma still resonates even in the workings of history, that are intended to elevate you.

Those remarks are certainly worth elaboration, and that elaboration will necessarily be interpretive in the fullest sense of the word.

Tuesday, August 30, 2016

Monday, August 29, 2016

Why Ethical Criticism? or: The Fate of Interpretation in an Age of Computation

Why is it that I am so insistent that interpretation be kept separate from reading? Why is it that I think that the profession’s desire to elide the difference between the two, to believe – heart and soul – is now counterproductive? Yes, I want to clear conceptual space for the description of formal features and for computational and otherwise mechanistic models of literary processes. But I also want to clear space for a forthright ethical criticism.

It is clear to me that textual meaning is something that is negotiated among critics (and their readers) through the process of interpretation. Such meaning cannot be objectively determined – though textual semantics could, at least in principle, be objectively modeled (but not yet, we don’t know how). In this usage, semantics is a facet of a computational model of mind while meaning is what happens in a mind that is articulating its encounter with a text. Yes, that’s a bit obscure, but I want to move on.

As I have articulated time and again, the creation of textual meaning through the interpretive process is a relatively new practice, dating back to the middle of the previous century, roughly speaking. We must understand it as new, not so we can supplant it with something newer still, but so that we can cultivate it without it having to bear the burden of being the central focus of the encounter between knowledge and art (as beauty, love, adventure). Naturalist criticism needs to be freed of interpretation so that it can pursue the description of form and the creation of psychological and neural models.

By the same token, ethical criticism needs the freedom to explore new ways of being human, ways that can be discovered through full responsiveness to literary texts (and other aesthetic objects). Interpretation is a vehicle for ethical response. Interpretation articulates possibilities of feeling and action. Evaluation passes judgment on whether or not these possibilities are to be pursued and even amplified.

Human “nature” IS NOT closed by human biology. Human biology leaves our nature open to cultural specification and elaboration. That’s where interpretation and evaluation come into their own, And THAT’s why I want to acknowledge that interpretation is different from (mere) reading. Interpretation must be acknowledged and developed as being essential to this enterprise.

That can happen ONLY when academic critics stop insisting, against all reason, that interpretation is really just reading on steroids (or something like that). It’s not. It’s new mode of knowing, a new mode of reading intersubjective agreement. It must be cultivated as such.

See Coltrane's Addendum, newly posted.

* * * * *

See Coltrane's Addendum, newly posted.

Vector-based representations of word meaning (& human bias)

Mark Liberman at Langauge Log has a useful post on a piece that's been making the DH rounds, Arvind Narayanan, "Language necessarily contains human biases, and so will machines trained on language corpora", Freedom to Tinker 8/24/2016:

We show empirically that natural language necessarily contains human biases, and the paradigm of training machine learning on language corpora means that AI will inevitably imbibe these biases as well.

Liberman continues:

This all started in the 1960s, with Gerald Salton and the "vector space model". The idea was to represent a document as a vector of word (or "term") counts — which like any vector, represents a point in a multi-dimensional space. Then the similarity between two documents can be calculated by correlation-like methods, basically as some simple function of the inner product of the two term vectors. And natural-language queries are also a sort of document, though usually a rather short one, so you can use this general approach for document retrieval by looking for documents that are (vector-space) similar to the query. It helps if you weight the document vectors by inverse document frequency, and maybe use thesaurus-based term extension, and relevance feedback, and …A vocabulary of 100,000 wordforms results in a 100,000-dimensional vector, but there's no conceptual problem with that, and sparse-vector coding techniques means that there's no practical problem either. Except in the 1960s, digital "documents" were basically stacks of punched cards, and the market for digital document retrieval was therefore pretty small. Also, those were the days when people thought that artificial intelligence was applied logic — one of Marvin Minsky's students once told me that Minsky warned him "If you're counting higher than one, you're doing it wrong". Still, Salton's students (like Mike Lesk and Donna Harman) kept the flame alive.

Mark goes on to discuss Google's "PageRank", "latent semantic analysis" (LSA), and more recent models. Liberman notes:

He then turns to Narayanan's post.It didn't escape notice that this puts into effect the old idea of "distributional semantics", especially associated with Zellig Harris and John Firth, summarized in Firth's dictum that "you shall know a word by the company it keeps".

Sunday, August 28, 2016

The A.D.H.D. Industrial Complex

The boundaries of the A.D.H.D. diagnosis have been fluid and fraught since its inception, in part because its allegedly telltale signs (including “has trouble organizing tasks and activities,” “runs about or climbs in situations where it is not appropriate” and “fidgets with or taps hands or feet,” according to the current edition of the DSM) are exhibited by nearly every human being on earth at various points in their development. No blood test or CT scan can tell you if you have the condition — the diagnosis is made by subjective clinical evaluation and screening questionnaires. This lack of any bright line between pathology and eccentricity, Schwarz argues, has allowed Big Pharma to get away with relentless expansion of the franchise.Numerous studies have shown, for example, that the youngest children in a classroom are more likely to be diagnosed with A.D.H.D. Children of color are also at higher risk of being misdiagnosed than their white peers. One clinician quoted in the book more or less admits defeat: “We’ve decided as a society that it’s too expensive to modify the kid’s environment. So we have to modify the kid.”Schwarz has no doubt that A.D.H.D. is a valid clinical entity that causes real suffering and deserves real treatment, as he makes clear in the first two sentences of the book: “Attention deficit hyperactivity is real. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.” But he believes that those who are disabled by the condition deserve a wider range of treatment options than an endless litany of stimulants with chirpy names like Vyvanse and Concerta.

And Big Pharma has been using ADHD to push pills:

While other books have probed the historical roots of America’s love affair with amphetamines — notably Nicolas Rasmussen’s “On Speed,” published in 2008 — “ADHD Nation” focuses on an unholy alliance between drugmakers, academic psychiatrists, policy makers and celebrity shills like Glenn Beck that Schwarz brands the “A.D.H.D. industrial complex.” The insidious genius of this alliance, he points out, was selling the disorder rather than the drugs, in the guise of promoting A.D.H.D. “awareness.” By bankrolling studies, cultivating mutually beneficial relationships with psychopharmacologists at prestigious universities like Harvard and laundering its marketing messages through trusted agencies like the World Health Organization, the pharmaceutical industry created what Schwarz aptly terms “a self-affirming circle of science, one that quashed all dissent.”

Over a decade ago I wrote up some notes of my own: Music and the Prevention and Amelioration of ADHD: A Theoretical Perspective. Here's the abstract:

Russell A. Barkley has argued that ADHD is fundamentally a disorientation in time. These notes explore the possibility that music, which requires and supports finely tuned temporal cognition, might play a role in ameliorating ADHD. The discussion ranges across cultural issues (grasshopper vs. ant, lower rate of diagnosis of ADHD among African-Americans), play, distribution of dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain, neural development, and genes in culture (studies of the distribution of alleles for dopamine receptors). Unfortunately, the literature on ADHD does not allow us to draw strong conclusions. We do not understand what causes ADHD nor do we understand how best to treat the condition. However, in view of the fact that ADHD does involve problems with temporal cognition, and that music does train one’s sense of timing, the use of music therapy as a way of ameliorating ADHD should be investigated. I also advocate conducting epidemiological studies about the relationship between dancing and music in childhood, especially in early childhood, and the incidence of ADHD.

Saturday, August 27, 2016

Yet Another Brief for Description (and Form)

These remarks are prompted by Ted Underwood’s tweets from the other day:

This helped me grasp an aesthetic problem w/ distant reading: it provides description at a scale where we expect interpretive synthesis.— Ted Underwood (@Ted_Underwood) August 17, 2016

Those tweets triggered my own long-standing puzzlement over why literary criticism has neglected the close and attentive description of literary form.

* * * * *

Let’s go to the text Underwood is referencing (see the link in his first tweet), Sharon Marcus, “Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis and the Value of Scale” (Modern Language Quarterly 77.3, 2016, 297-319). She uses description, interpretation, explanation, and evaluation as her analytic categories (304). And, while her discussion tends to circle around a ‘dialectic’ of description and interpretation, she also emphasizes Auerbach’s use of evaluative language: “Mimesis may owe its lasting allure to Auerbach’s complex relationship to the language of value” (300). And then (301):

Certain adjectives have consistently positive or negative valences in Mimesis: rich, wide, full, strong, broad, and deep are always terms of praise, while thin, narrow, and shallow always have negative connotations. Tellingly, Auerbach’s values are themselves related to scale; his epithets suggest that he prefers what is large and dense to what is small and empty, the river to the rivulet.

Such evaluative terms link Auerbach’s criticism to the existential concerns that, in the conventional view (which I do not intend to contest), motivates our interest in literature in the first place. Those concerns are ethical and aesthetic, but, as Marcus notes, such evaluative matters where bracketed out of professional consideration back in the 1960s though they have returned in the form of critique (306). Auerbach was writing before that dispensation took hold and so was free to use evaluative language to link his discussion, both at the micro-scale of individual passages and the macro-scale of Western literary history, to his (and our) life in the here and now.

Distant reading, however, is fundamentally descriptive in character, as Underwood notes. Moreover, as Franco Moretti has asserted in interviews and publications, he pursues distant reading because he seeks explanations, not interpretations. That is, he sees an opposition between interpretation and description. And this is where things begin to get interesting, because I suspect that Underwood would prefer not to see things that way and Marcus seems to be resisting as well. That is, they would prefer to see them working in concert rather than opposition.

But look at what Marcus says about explanation (305-306):

Explanation designates the operation by which literary critics assign causality, though explanation can also signify description and interpretation, as when we “explain” a poem. Literary critics tend to downplay causality — “why?” is not our favorite question — and usually refer the sources of a text’s meaning or form to disciplines other than literary criticism, such as history, biography, economics, philosophy, or neuroscience. Thus scholars often relate specific features of literary works to general phenomena such as modernity, capitalism, imperialism, patriarchy, or the structure of our brains. But because explanation is an undervalued operation in literary criticism, one seen to depend on the kind of literalism that leads many critics to reject description as impossible, the exact nature of the link between general phenomena and specific works often remains nebulous. Literary critics are more likely to posit the relationship between the realist novel and capitalism as one of homology, analogy, or shared commitments (to, say, individualism) than they are to trace a clear line from one as cause to the other as effect.

In practice, literary critics neglect precisely what Moretti seeks, explanation. When Marcus asserts the literary critics like to talk of “homology, analogy, or shared commitments,” she is in effect saying that they talk of interpretation.

That is, in terms of actual practice if not in abstract methodological terms, interpretation and explanation are, as Moretti sees, alternative forms of causal explanation. “Classically,” if I may, the cause of a text is the author; the classical critic seeks the author’s intention as the source of a text’s meaning. Why is the text what it is? How did it come into being? The author did it. Post-classically, the author got bracketed out in favor of social, semiotic, and psychological forces operating through the author. It is those forces that bring the text into existence and are the source of its meaning. The post-classical critic then smuggles evaluation in by way of critique, thereby completing the circuit and linking criticism to those existential concerns – what is the good? how do I live? – that motivate literature itself.

This is a nice trick, and it is “sold” by the ruse of calling interpretation “reading,” thus making it appear to be continuous with the ordinary activity of reading as practiced by those very many readers who have never taken any courses in literary criticism (or have forgotten them long ago) much less become proficient in one or more of the various schools of interpretation and critique. Interpretive proficiency does not come “naturally” in the way that learning to speak does. It requires years of practice and tutelage at an advanced level.

Friday, August 26, 2016

Friday Fotos: Welcome to Eden: The Bergen Arches

Since it's Bergen Arches week in Jersey City I thought I'd bump one of my many Bergen Arches posts to the top of the queue.

The local name for the phenomenon, the Bergen Arches, is a bit well, odd. Yes, there are arches, five of them; two are bridges and three are short tunnels. You see them when you are there, but what you really see is the Erie Cut, a trench cut through Bergen Hill, which is the southern tip of the Jersey Palisades.

The Cut is 85 feet deep and almost a mile long. It was cut into solid rock in the early 20th century to bring four railroad tracks to the port at Jersey City. Jersey City - like Hoboken to its immediate North (where “On the Waterfront” was set) - is no longer a port city; those tracks have been abandoned and only one of them remains. No one goes into the Cut except graffiti writers, historic preservationists, and other assorted miscreants and adventurers.

Once you're in the Cut you're in another world. Yes, New York City is two or three miles to the east across the Hudson and Jersey City is all over the place 85 feet up. But down in the Cut, those places aren't real. The Cut is its own world, lush vegetation, crumbling masonry, rusting rails, trash strewn about here and there, mud and muck, and mosquitoes, those damn mosquitoes! Nope, it's not Machu Pichu and it's not Victoria Falls, but it's pretty damn good for being in the middle of one of the densest urban areas in the freakin' world.

Is Description [FINALLY!] Coming of Age in Literary Criticism? [AT LONG FREAKIN’ LAST!]

Description, of course, has been kicking around for awhile. It’s part of a critical quartet articulated by Monroe Beardsley in the 1950s: description, analysis, interpretation, and evaluation. Stanley Fish took it to task in Is There a Text in This Class? where he castigates Steven Booth for asserting that he was but describing Shakespeare’s sonnets (p. 353):

The basic gesture, then, is to disavow interpretation in favor of simply presenting the text; but it is actually a gesture in which one set of interpretive principles is replaced by another that happens to claim for itself the virtue of not being an interpretation at all. The claim, however, is an impossible one since in order “simply to present” the text, one must at the very least describe it ... and description can occur only within a stipulative understanding of what there is to be described, an understanding that will produce the object of its attention.

And that’s where things have pretty much rested until recently.

In 2010 Heather Love published an essay that got a fair amount of buzz, Close but not Deep: Literary Ethics and the Descriptive Turn (New Literary History, 41, No. 2, 371-391). After citing Bruno Latour on the importance of description, Love takes a look at Toni Morrison’s Beloved, but NOT to describe features of Morrison’s text. Rather, she’s interested in Morrison’s use of description IN her text. If Latour describes the phenomena that interest him, why doesn't Love do the same? Why does she displace her descriptive desire into Morrison's text?

More recently Sharon Marcus discusses description, interpretation, explanation, and evaluation in the course of analyzing Auerbach’s method in Mimesis in Modern Language Quarterly. She notes (p. 298):

For the past several decades, the most celebrated literary critics have tended to value interpretation, connotation, and the figurative over description, denotation, and the literal, arguing that the latter set of terms names operations that are impossible to carry out. Literary critics often rally around the preferred terms by casting them as methodological underdogs in need of defense against an allegedly dominant empiricist positivism that no longer prevails even in the sciences.

She goes on to show the Auerbach makes frequent use of description while distinguishing it from interpretation (308) and to argue that we value Auerbach because of his use of description (309).

And now Marcus has conspired with Heather Love and Stephen Best to edit an issue of Representations (Summer 2016) devoted to description. What next?

representations

Summer 2016 • Number 135

SPECIAL ISSUE: Description Across Disciplines

Edited by Sharon Marcus, Heather Love, and Stephen Best

LIZA JOHNSON –

Observable Behavior 1–10, page 22

KATHLEEN STEWART

–

The Point of Precision, page 31

LORRAINE DASTON –

Cloud Physiognomy, page 45

JOANNA STALNAKER –

Description and

the Nonhuman View of Nature, page 72

GEORGINA KLEEGE – Audio Description Described: Current Standards, Future Innovations, Larger Implications, page 89

CANNON SCHMITT –

Interpret or Describe? page 102

JILL MORAWSKI –

Description in the Psychological Sciences, page 119

MICHAEL FRIED –

No Problem, page 140

Thursday, August 25, 2016

The mystery of humanistic epistemology in 5 tweets and a link

This helped me grasp an aesthetic problem w/ distant reading: it provides description at a scale where we expect interpretive synthesis.— Ted Underwood (@Ted_Underwood) August 17, 2016

@bbenzon I agree, obvs. But I'm really trying to understand the reluctance. Much of it is simple inertia, but part is something else.— Ted Underwood (@Ted_Underwood) August 25, 2016

@Ted_Underwood Yes on something else. Maybe it's the same 'something else' blocking attentive description of single texts.— Bill Benzon (@bbenzon) August 25, 2016

The cognitive linguists like to talk about 'human scale.' One of the things that happens in conceptual blending, as they call it, is that phenomena can be repackaged from their own 'natural' scale to human scale. Is that what interpretation does that the descriptive methods of 'distant reading' don't do?

Wednesday, August 24, 2016

Digital Resistance & Anti-Neoliberal Hype [#DH]

From Whitney Trettien, Creative Destruction/"Digital Humanities":

H/t:Today, the digital turn in its various constellations offers the best potential for fostering resistance to the conservative forces that seek to devalue interpretive inquiry. This is because the nature of the work itself forces scholars to attend to that frictive zone where critical acts are taken up by technologies, woven into the material world, and entangled within a network of social and cultural practices. The pressures of this seemingly new kind of work have opened a fruitful space of collaborative inquiry around issues like the politics of information storage, the economics of the scholarly monograph, and the role of the public domain. By drawing attention to systems of mediation, this shift has also galvanized discussion around access and disability, as well as the critical valences of different modes of representation and how they invisibly shape discourse. And it has empowered scholars to take publishing (by which I simply mean making an idea public) under their own control while developing frameworks for accreting value to previously undervalued practices, such as editing, technical design, and creative criticism. Of course, simply engaging in digital or collaborative scholarship alone won’t result in a more equitable academy, nor is such work any more inherently resistant than “literary-interpretive practices” are. Rather, the productive entanglement of the humanities’ interpretive work and its self-conscious mediation holds the greatest possibility for catalyzing change right now.This possibility has most been realized at the fecund node where the concerns of book history, media studies, information sciences, and digital scholarship meet. I don’t think this is an accident. Historians of information and media technologies deal with tangible objects and infrastructures, and as such are accustomed to thematizing the points of contact between immaterial ideas and the material systems that store, archive, and communicate them. Scholars working across these areas know well that archives are not neutral zones of accumulation but battlegrounds of interpretation; that no discourse remains untainted by the technologies that mediate it; and that moments of media transition — which are all moments — are always hybrid, containing simultaneously progressive and regressive values. Because of their methodological commitments, these fields are capable of historicizing the emergence of electronically-mediated methods, thereby deconstructing the false oppositions that often unwittingly guide both critics and advocates, such as humanities/neoliberalism or thinking/making. Thus historians of text technologies are best poised to seize the technological and rhetorical upheavals of our time as an opportunity to restructure the humanities in ways that are both more culturally salient and politically potent.

Brilliant. The 2 paras. starting at “This is the problem, and the danger”, & ensuing historical exemplum are gold. https://t.co/Sfh51XPTB9— Alan Liu (@alanyliu) August 24, 2016

Tuesday, August 23, 2016

My Early Jazz Education 4: Thelonius Sphere Monk

And then there’s Thelonius Sphere Monk. The album was Thelonious Monk Big Band and Quartet in Concert. I don’t know how I came across that album, but it stunned me, though it took some getting used to. At that point Maynard Ferguson’s early 1960s band was my idea of a big band. Monk’s band, not his usual performance context, wasn’t at all like that. Not that big, nor that brassy. And, of course it was Monk. Here’s the personnel:

Arranger: Hall Overton

Bass: Butch Warren

Alto Saxophone, Clarinet: Phil Woods

Tenor Saxophone: Charlie Rouse

Baritone Saxophone, Bass Clarinet, Clarinet: Gene Allen

Soprano Saxophone: Steve Lacy

Trumpet: Nick Travis

Trombone: Eddie Bert

Cornet: Thad Jones

Let’s listen to “Bye-Ya,” a Monk original:

Notice that the cut is 11:24, longer than anything I’d heard. The length is in the solos. The tune is a standard AABA tune. But, upon closer listening, not so standard. To a first approximation the harmony’s pretty static, with little excursions at the end of each 8 bar phrase. We don’t have a strong sense of tonal center, which makes this pretty advanced for its time.

Which Monk was. Advanced. Monk is generally classed with bebop. He worked with a lot of boppers, and he emerged when bop did. But he was halfway to 1960s modal music and mid-1960s “out” music.

Here's Monk's “Epistrophy” in a quartet version:

It too is AABA. The A section used a simple 2-bar riff repeated four times, with subtle variations. The B section (aka the bridge) has a more developed melody. So, melodically, it’s riffs in the A section against an actual melody in the B.

Harmonically, like “Bye-Ya,” the tonal center is weak. Now, listen closely to the A section, which is two closely related 2-chord vamps. We’ve got D-flat 7 to D7 for four bars, and then E-flat 7 to E7 for four bars. Like so:

Db7 D7|Db7 D7|Db7 D7|Db7 D7|Eb7 E7|Eb7 E7|Eb7 E7|Eb7 E7|

So, do whatever makes sense over Db D7 for four bars, and then take it up half a step for the next four. That’s the structure you’ve got work with. It’s either little or nothing, or very subtle, depending on your skill.

Monday, August 22, 2016

Markos Vamvakaris, Rebetiko Master, @3QD

I’ve got another piece up at 3 Quarks Daily: Markos Vamvakaris: A Pilgrim on Ancient Byzantine Roads. It’s a review of his autobiography, Markos Vamvakaris: The Man and the Bouzouki, as told to Angeliki Vellou-Keil and translated into English by Noonie Minogue.

|

| Markos Vamvakaris in 1967 |

Here’s a note I sent to Charlie Keil, Angeliki’s husband, while I was reading the book:

I’m now 57 pages into the Markos autobiography and beginning to get the barest hint of how to deal with it for 3QD. The easy thing, of course, would be to treat him as an exotic primitive. I think, in fact, that it will be difficult NOT to treat him in that way. But I’m beginning to get a sense of how I can, if not completely avoid that, at least to subject that temptation to some humanizing discipline.I very quickly started comparing him with Louis Armstrong. Both were born poor and had difficult early lives, both lived among criminals and reprobates, both were involved with drugs, and, of course, both eventually became nationally recognized musicians. And Armstrong, of course, wrote his own autobiography, albeit early in life, which was then edited into shape. And he wrote (often long) letters all his long. So there is that. But it’s not clear how far this gets me.But then we have the fact of Markos’ songs appearing in the text near events to which they are somehow tied. And so they are contextualized. THAT’s the barest hint.And then there’s the odd and, yes, exotic part of the world he comes from. Except that we in the West have the myth of the origins of Western culture in ancient Greece, Rome, and Jerusalem. And yeah well sure, except that those places would appear very exotic indeed to any modern civilized Westerner who would time-travel back to them. But then we treat contemporary musicians and performers (of all kinds) as exotics, don’t we? It’s a curious business.And I’ve got a question, perhaps for Angie. In her appendix she refers (p. 284) to “the dhromos (path) or maqam of each song”. I’m curious about the word “maqam.” I know it as Arabic for melodic mode. Is she using it as an Arabic term that’s equivalent to “dhromos” or has the term been adopted into Greek?

Yes, maqam was taken into Greek. Same word, same meaning. This is a part of the world where the difference between Europe and Asia Minor has more to do with lines drawn on maps than with the lifeways of the people living there.

Here’s the opening paragraph of the review Charlie posted to Amazon.com; it talks about just how such a book is gathered together:

I am biased, of course, because I know that my wife, Angeliki Vellou Keil, worked very hard to pull the transcriptions of taped interviews together for this book. It took over a year of daily visits to a little office around the corner from our house in Buffalo, patiently shaping different pieces of interviews together for each chapter. I often looked at Alan Lomax's Mr. Jelly Roll as an early example of an as-told-to book. He made it look so easy to do. And David Ritz is another master of this craft, sometimes turning out 2 or 3 books a year by recording, transcribing, and sequencing the events and opinions, editing out any excesses of profanity, or leaving out a passing on of ugly rumors. His books, some of them very long and fully detailed, always feel natural, true to life – again it looks easy. But take it from a friend of David's and a witness to wife Angeliki's labors, there are a lot of decisions to make about how many repetitions to leave in, and when does it seem prudent to leave a love affair out, or to put some particularly nasty insult or criticism of someone aside. At all times Angie insisted on keeping it just the way Markos spoke it, sticking to the transcription, and that turned out to have some unexpected benefits.

Even if it made it difficult to untangle at points. But it’s worth your serious attention.

Sunday, August 21, 2016

Melissa Dinsman interviews Richard Grusin in the last LARB interview on DH

Where should the work be done? departments, libraries, labs?

...one of the things I really loved, more than even the networked computer classroom, was the computer lab for our masters program. I would go in the lab regularly to just kind of kibitz and chitchat and see what was going on with people, because at almost any hour of the day there would be some grad student in there working. It was a fun environment: it was loose, informal, collaborative, and the hierarchies broke down — I was the student. So I’m a huge fan of labs. I think one of the positive aspects of the digital humanities has been the creation of these kinds of open and different spaces.How do you think the general public understands the term “digital humanities” or, more broadly, the digital work being done in the humanities (if at all)?My first inclination is to say not much. But I think there are two places where digital work in the humanities is being done, and often being done outside the academy. One of these places is participatory culture. There has been an explosion of students writing online, be it blogging or fan fiction or whatever. And I think this is really one of the places where digital work in the humanities is being done as a result of changes in technology. We haven’t really made enough of a connection between this kind of participatory culture and the classroom, but I think we are moving in that direction. The other place is in the classroom. We think of the public in a kind of consumerist way. But our students are also the public. As college is becoming more and more universal, all of those students who are taking humanities courses are part of the public, and I don’t think most of them understand the digital humanities. DH is a branding tool for faculty and getting resources.

Saturday, August 20, 2016

American science rests on foundations funded by the Department of Defense

Americans lionize the scientist as head-in-the-clouds genius (the Einstein hero) and the inventor as misfit-in-the-garage genius (the Steve Jobs or Bill Gates hero). The discomfiting reality, however, is that much of today’s technological world exists because of DOD’s role in catalyzing and steering science and technology. This was industrial policy, and it worked because it brought all of the players in the innovation game together, disciplined them by providing strategic, long-term focus for their activities, and shielded them from the market rationality that would have doomed almost every crazy, over-expensive idea that today makes the world go round. The great accomplishments of the military-industrial complex did not result from allowing scientists to pursue “subjects of their own choice, in the manner dictated by their curiosity,” but by channeling that curiosity toward the solution of problems that DOD wanted to solve.Such goal-driven industrial policies are supposed to be the stuff of Soviet five-year plans, not market-based democracies, and neither scientists nor policymakers have had much of an appetite for recognizing DOD’s role in creating the foundations of our modern economy and society. Vannevar Bush’s beautiful lie has been a much more appealing explanation, ideologically and politically. Not everyone, however, has been fooled.

Bush's beautiful lie, "Scientific progress on a broad front results from the free play of free intellects, working on subjects of their own choice, in the manner dictated by their curiosity for exploration of the unknown." The truth:

First, scientific knowledge advances most rapidly, and is of most value to society, not when its course is determined by the “free play of free intellects” but when it is steered to solve problems — especially those related to technological innovation.Second, when science is not steered to solve such problems, it tends to go off half-cocked in ways that can be highly detrimental to science itself.Third — and this is the hardest and scariest lesson — science will be made more reliable and more valuable for society today not by being protected from societal influences but instead by being brought, carefully and appropriately, into a direct, open, and intimate relationship with those influences.

Especially interesting in the context of recent discussions about 'digital humanities' and 'neoliberalism.'

H/t 3QD.

Friday, August 19, 2016

Writing, computation and, well, computation

…continuing on…more thinking out loud…

Some years ago I published a long theory&methodology piece, Literary Morphology: Nine Propositions in a Naturalist Theory of Form. In it I proposed the literary form was fundamentally computational. One of my reviewers asked: What’s computation?

Good question. It wasn’t clear to me just how to answer it, but whatever I said must have been sufficient, as the paper got published. And I still don’t have an answer to the question. Yes, I studied computational linguistics, I know what THAT computation was about. But computation itself? That’s still under investigation, no?

Yet, if anything is computation, surely arithmetic is computation. And here things get tricky and interesting. While so-called cognitive revolution in the human sciences is what happened when the idea of computation began percolating through in the 1950s, it certainly wasn’t arithmetic that was in that driver’s seat. It was digital computing. And yet, arithmetic is important in the abstract theory of computation, as axiomatised by Peano and employed by Kurt Gödel his incompleteness theorems.

Counting

Let’s set that aside.

I want to think about arithmetic. We know that many preliterate cultures lack developed number systems. Roughly speaking, they’ll have the equivalent of one, two, three, and many, but that’s it. We know as well that many animals have a basic sense for numerosity that allows them to distinguish small number quantities (generally less than a half-dozen or so). It seems that the basic human move is to attach number terms to the percepts given by the numerosity sense.

Going much beyond that requires writing. Sorta’. We get tally marks on wood, stone, or bone and the use of clay tokens to enumerate herd animals. The written representation of language comes later. That is, it would appear that written language is the child of written number.

But it is one think to write numbers down. It is another thing to compute with them. Computing with Roman numerals, to give the most obvious example, is difficult. And it took awhile for the Hindu-Arabic system to make its way to Europe and be adopted there.

The exact history of these matters is beside the point. The point, rather, is that there IS a history and it is long and complex. Plain ordinary arithmetic, that we teach to school children, is a cultural accomplishment of considerable sophistication.

Thursday, August 18, 2016

What’s Computation? What’s Literary Computation?

Continuing a line of thought from yesterday… More thinking out loud.

I’m interested in both of the title questions. But, for the purposes of this post, I’m interested in the first question mainly because I figure that thinking about it will help me answer the second question. That’s the one that really interests me.

Concerning that first question, as far as I can tell, it’s under investigation. Yes, we’ve been doing calculation for like years and years and centuries and even longer. But the emergence of modern computing technology involves more than just packaging already existing computational know-how into new physical devices. The act of packaging computation into those devices has forced us to re-think computation, and we’re still working on it.

As for literary computing, by which I mean the computational processes underlying literary texts, that is little more than a dream. For the most part, we have to invent it. We can’t just take some off-the-shelf (OTS) computing tech and applying to literary texts.

Where I’m currently going is that literary form is computational. I don’t know how to get there, but I figure a way of starting is to think about ordinary conversation as computational in kind.

How so?

Simulation and Phenomena

This is tricky. There are those who think that whatever the brain does, it’s computational in nature. I might even be one of those on one day out of ten. If that’s the case, then of course computation is computational. THAT doesn’t interest me.

What makes this tricky is that digital computers can be used to simulate many different phenomena. That doesn’t mean that those phenomena are themselves computational. It is one think to simulate an atomic reaction on a computer and another thing entirely to initiate one in a reactor or a bomb. The physical phenomenon is one thing; its computational simulation is something else.

That’s clear enough. Where things get murky is when we’re talking about minds and brains. Walter Freeman, for example, used computers to simulate the dynamics of neural systems. Does that mean that the physical process being enacted by those neurons is itself a computational process? Some would say, yes, but I suspect that Freeman would say, no, it’s not computational. It’s something different. That is, Freeman makes the same distinction between physical phenomenon and simulation that the physicist or nuclear engineer makes in the case of nuclear reactions.

Conversation IS computation

I’m willing to go along with Freeman on this one, at least on, say, three days out of five. And that’s kind of the position I want to take in the case of conversation. But, with that distinction in place, I want to say is that conversation is in fact a computational process. Which implies that, if we use a computer to simulate conversation, then we’re using one kind of computation, artificial digital computation, to simulate another kind of computation, natural digital/analog computation. For the purposes of a certain line of thought, a line of thought that leads to the analysis and description of literary form, conversation is the prototypical form of computation.

On this view apes do not engage in computation, not when they perceive and act in the world, not when they interact with one another through gestures that seem conversation-like. That’s something else. In the human case, conversation/computation is implemented in processes that are not themselves computational.

If that is the case, then what are the basic computational processes? I’m thinking that there’s the binding of sound to sense, and there’s the mechanisms of conversational repair. But, to the extent that apes exhibit turn taking in gestural interaction, turn-taking would not computational in kind. Rather, it belongs to the sensorimotor equipment in which conversational computation is implemented.

Can I live with this? I don’t know. I just made it up. Can I construct an account of literary form from this, or at least motivate such an account, that’s the question. We’ll see.

* * * * *

And it is the conversation-as-computation – or it is computation-as-conversation? – that is the root of the cultural evolutionary process that will yield arithmetic computation and, eventually, digital computers and the abstract theory of computation. This is most peculiar and tricky.

These mechanisms are at the borderline of consciousness.

To be continued.

Wednesday, August 17, 2016

Words, Binding, and Conversation as Computation

I’ve been thinking about my draft article, Form, Event, and Text in an Age of Computation. It presents me with the same old rhetorical problem: how to present computation to literary critics? In particular, I want to convince them that literary form is best thought of as being computational in kind. My problem is this: If you’ve already got ‘it’, whatever it is, then my examples make sense. If you don’t, then it’s not clear to me that they do make sense. In particular, cognitive networks are a stretch. Literary criticism just doesn’t give you any useful intuitions of form as being independent of meaning.

Any how, I’ve been thinking about words and about conversation. What I’m thinking is that the connection between signifier and signified is fundamentally computed in the sense that I’m after. It’s not ‘hard-wired’ at all. Rather it’s established dynamically. That’s what the first part of this post is about. The second part then goes on to argue that conversation is fundamentally computational.

This is crude and sketchy. We’ll see.

Words as bindings between sound and sense

What is a word? I’m not even going to attempt a definition, as we all know one when we see it, so to speak. What I will say, however, is that the common-sense core intuition tends to exaggeration their Parmenidean stillness and constancy at the expense of the Heraclitean fluctuation. What does this word mean:

race

It’s a simple word, an everyday word. Out there in the middle of nowhere, without context, it’s hard to say what it means. I could mean this, it could mean that. It depends.

When I look it up in the dictionary on my computer, New Oxford American Dictionary, it lists three general senses. One, “a ginger root,” is listed as “dated.” The other two senses are the ones I know, and each has a number of possibilities. One set of meanings has to do with things moving and has many alternatives. The other deals with kinds of beings, biological or human. These meanings no doubt developed over time.

And, of course, the word’s appearance can vary widely depending on typeface or how it’s handwritten, either in cursive script or printed. The spoken word varies widely as well, depending on the speaker–male, female, adult, child, etc.–and discourse context. It’s not a fixed object at all.

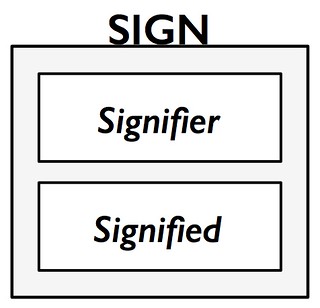

What I’m suggesting, then, is that this common ‘picture’ is too static:

There we have it, the signifier and the signified packaged together in a little ‘suitcase’ with “sign” as the convenient handle for the package. It gives the impression the sentences are little ‘trains’ of meaning, with one box connected to the next in a chain of signifiers.

No one who thinks seriously about it actually thinks that way. But that’s where thinking starts. For that matter, by the time one gets around to distinguishing between signifier and signified one has begun to move away from the static conception. My guess is that the static conception arises from the fact of writing and the existence of dictionaries. There they are, one after another. No matter when you look up a word, it’s there in the same place, having the same definition. It’s a thing, an eternal Parmenidean thing.

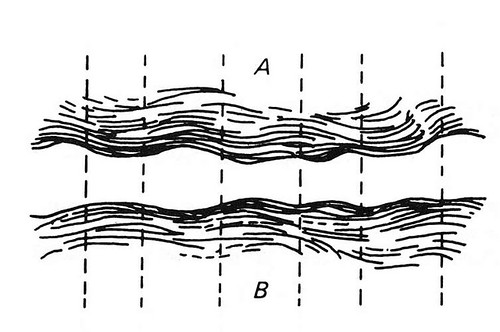

Later in The Course in General Linguistics, long after he’s introduced the signifier/signified distinction, de Saussure presents us with this picture [1]:

He begins glossing it as follows (112): “The linguistic fact can therefore be pictured in its totality–i.e. language–as a series of contiguous subdivisions marked off on both the indefinite plane of jumbled ideas (A) and the equally vague plane of sounds (B).” He goes on to note “the somewhat mysterious fact is rather that ‘thought-sound’ implies division, and that language words out its units while taking shape between two shapeless masses.” I rather like that, and I like that he chose undulating waves as his visual image.

Tuesday, August 16, 2016

Small schools punch above their weight on tech innovation

From Howard Rheingold's profile of digital educator Bryan Alexander:

My experience with large institutions such as Stanford and smaller, less brand-famous institutions such as the University of Mary Washington, led me to the same conclusion as Alexander: “Some of these private, undergraduate-focused, smaller institutions punch above their weight when it comes to technology innovation. We worked closely with these schools and experimented with variety of tools and pedagogies — GIS mapping, social media on mobile devices, digital story-telling. We used technologies to talk about how to use technologies — video conferencing to help explain video conferencing. Social media. I built and ran a prediction market game for a few years.” Since 2014, Alexander has struck out on his own as a “consulting futurist” for educators.

Social equity:

“First is the social equity benefit. If you go to a library in the developing world, you’ll find them usually packed with people but lacking a lot of materials. And, one reason is because they can’t afford to ship in a lot of books and journals. They can’t afford a lot of the developed world prices. Open education resources for those libraries are a godsend. You think about the same as a learner. You’re working in Ghana, you’re 15 or maybe you’re in North Africa and you would really like to make more of your life. You have access to the world through your phone but how much of American higher education is not available that way, even when it’s in digital form? How much do we bury behind pay walls or lock in the tombs of closed, proprietary systems? So for equity reasons, for just decency reasons, we have to open our trove for the world.”

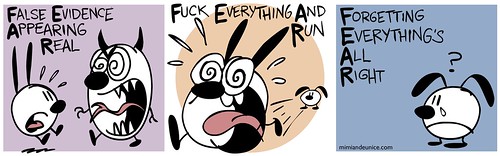

The trouble with PEACE is FEAR

Courtesy of Nina Paley

The trouble with organizing politics around peace is that there are a lot of angry people in the world, and they need targets for that anger. The Donald Trumps of the world are good at finding targets for that anger. Peace, as a cause, doesn't present a natural opportunity for political target shooting. Who are the enemies of peace? They're your friends and neighbors, who are angry at immigrants, abortionists, women's libbers, Muslims, and whoever is taking their jobs. It's pretty hard to turn that around and point it in the direction of peace. Rational arguments can't overcome that need for targets.

Monday, August 15, 2016

Sunday, August 14, 2016

Knowledge as Intersubjective Agreement, a Quickie

There are matters for which we have methods that allow for “tight” intersubjective agreement. There are other matters which no known methods allow for “tight” intersubjective agreement. Science and math are as tight as these things get. Perhaps the revealed truths of religion are up there, but those truths turn out to be endlessly open to interpretation, and that can lead to sectarian divisions, which in turn give rise to some of the bitterest conflicts we’ve got. Then we’ve got simple matters like whether or not it’s raining outside. How do we settle those kinds of questions? We look out the window or step outside. Such matters generally yield intersubjective agreement.

And that, it seems to me, is the point: intersubjective agreement. That’s necessary if we are to speak of knowledge. But knowledge comes in all kinds, for there are many ways of reaching intersubjective agreement.

From my open letter to Charlie Altieri:

I am of the view that the rock-bottom basic requirement for knowledge is intersubjective agreement. Depending how that agreement is reached, it may not be a sufficient condition, but it is always necessary. Let’s bracket the general issue of just what kinds of intersubjective agreement constitute knowledge. I note however that the various practices gathered under the general rubric of science are modes of securing the intersubjective agreement needed to constitute knowledge.As far as I know there is no one such thing as scientific method – on this I think Feyerabend has proven right. Science has various methods. The practices that most interest me at the moment were essential to Darwin: the description and classification of flora and fauna. Reaching agreement on such matters was not a matter of hypothesis and falsification in Popper’s sense. It was a matter of observing agreement between descriptions and drawings, on the one hand, and specimens (examples of flora and fauna collected for museums, conservatories, and zoos) and of creatures in the wild.

A quick note about "Sausage Party"

I haven't laughed this hard since The Aristocrats – a decade ago, gasp! But only at the food orgy at the end. Before that, chuckles and giggles, but nothing that threatened a urinary accident.

Sausage Party opens in a supermarket, Shopwell's, and spends much of its time there, but with unpleasant excursions to the outside world, known as "The Great Beyond" to the items stocking the shelves. It is their hope to be chosen by the gods, that is, shoppers, to be taken to a wonderful life in that great beyond. The film follows a group of groceries into the outer world and witnesses their grisly and painful disillusionment upon discovering that it is their fate in life to be eaten. But some of them return to tell the tale.

Meanwhile, Frank, a sausage, loves Brenda, a bun. They have their own adventures inside the store. She with a lesbian taco. And he with Firewater, a bottle of liquor, and his kazoo-toking cronies (including I kid you not a Twinkie). They tell Frank the truth, which he verifies when he discovers a cookbook and looks inside. So Frank sets about the thankless task of trying to convince the others that The Great Beyond is an imaginary hope.

Before this a jar of Honey Mustard had been returned to the store. He saw the truth and didn't like it. He's on his own mission of grim-truth-telling even as an angry douche is on the loose and causing trouble. You won't believe where that douche finally meets his destiny. OK, yes, by the time we get there, you'll believe it. And the wiener visual pun.

Before this a jar of Honey Mustard had been returned to the store. He saw the truth and didn't like it. He's on his own mission of grim-truth-telling even as an angry douche is on the loose and causing trouble. You won't believe where that douche finally meets his destiny. OK, yes, by the time we get there, you'll believe it. And the wiener visual pun.

Nice bits throughout, clever bits, funny bits. And I kept thinking: This can't possibly work out! What kind of victory is possible for these fruits, vegetables, meats, potatoes, condiments, baked items, assorted nutritional liquids, and packaged goods? They were created by humans, even if they don't know it, for consumption by humans, which they're now discovering to their dismay. So they stage a revolt, so they manage to subdue the staff of the supermarket and the "gods" wandering the aisles, so what? How long can such a victory last? Not long, not long at all. So what's the point?

Every few minutes I'd run that down in my mind, not so discursively, just a flash for a second or two. Even so, the jokes and the action. In one scene we see a potato being peeled before being dropped in boiling water. It was kinda' shocking. We knew what was going to happen, we could see it coming – are they really going to go there? – after the woman had put the water on to boil, then reached to the countertop, grabbed the potato, giddy with joy at being handled, pleased as she scrubbed it, and then shocked and screaming upon being peeled.

Graphic violence, against a talking potato! I've seen some grisly movies and TV shows, some where people were cruelly tortured, but I've never actually seen the skin being sliced from a living body. Substitute a potato, put it in a cartoon, and it was actually a bit shocking. Even as I knew it would happen, I was a bit shocked to see the potato peeled before my eyes on the screen (though I've done such things many times in real life). Yes, cartoon violence is notoriously anodyne, but not this, suspended between the reality of torturing and murdering humans, the reality of peeling vegetables, and the reality of Itchy and Scratchy destroying one another for one seven minute romp after another. And somehow the decapitated head of a drug-using loser-human ends up in an aisle, after which we see how that happened, though we don't actually see the ax slice into the neck.

And, there it was, popping into my mind again: this can't end well. A wad of chewing gum spouting physics and disguised as Stephen Hawking? No! Can't end well, no it can't.

It's a matter of logic. We know that cartoons posit impossible things in an impossible world. That's fine, as long as they're internally consist about that impossible world, things are fine. But this whole misadventure seemed to rest on a premise that can't possibly deliver on any kind of ever-after, much less a happily ever-after. So these fruits, meats, buns, and paper goods manage to destroy the entire agribusiness complex, what then? Talk about your scorched earth!

Apocalypse Now!

But that food orgy just before the FINAL REVELATION, that had us rolling in the aisles. Not really, but you get the idea. There were only 30 or 40 of us in the theater, it was a mid-afternoon showing, but we laughed for a 100. It was that funny. Polymorphous perversity on intergallactic overdrive, but only foodstuffs and packaged goods. Left nothing and everything to the imagination.

Lots of filthy language, but not quite up there with The Aristocrats. That was wall-to-wall filth, but no vegetables and shopping carts.

Worth the price of admission.

Worth the price of admission.

Saturday, August 13, 2016

A Young Girl Rocks Out on Keyboard

Dan Everett posted shared this on his Facebook page and I thought I’d say a few words about her playing. I managed to find it on YouTube:

The commenters there identify the piece as Sonatina in D Major, Op 36, No 6 by Muzio Clementi. I wouldn’t have guessed that, but then, I simply don’t know Clementi. But that’s irrelevant.

I want to talk about her playing. Actually, I want to talk about how she uses her body. She plays with her body, as any halfway decent musician does. Look at how her upper body moves once she’s underway. That’s not merely a matter of moving her arms back and forth in front of the keyboard, it is some of that. It’s mostly keeping the groove and it’s setting the muscle tone in which her arms and fingers make the more differentiated movements that activate the keys.

Look, hear how strong her left hand is at 0:22 as she walks it back and forth. She’s leaning into it. And again at 0:34. Meanwhile the right hand is playing scalar figures.

The hands punctuate together at roughly 0:40, marking a turning point in the music. Listen to the left hand chords at 0:54, which are repeated an octave lower at 0:58 – well, not really repeated. But similar chordal figures, and she digs in. The young lady has a firm grasp of the piece’s structure and it comes out especially in her left hand. Hands together at 1:01. Look at/listen to her left hand just before the page turn and then hands together 1:05-1:09.

Now we move to the next section of the piece (I’m sure there’s a technical name for it, but I don’t know it). The left hand just keeps thumping away on a static figure – little or no motion up or down – while the right hand diddles the scalar melodic figures. And now an excursion into minor territory at 1:28. The left hand heads to the basement at 1:34.

She really digs in (left hand) 1:38-1:42, and then backs off on the volume (watch her body here), a short break and back to the beginning at 1:44.

The power at 2:04, 2:13, 2:15. Then she backs off. Watch hands and body at the end, 2:40-2:44.

Friday, August 12, 2016

My Early Jazz Education 3: Herbie Mann and Dave Brubeck

Of course, it wasn’t all trumpet music that I listened to, just mostly.

Really, mostly?

Yeah, pretty near.

Somehow I found my way to Herbie Mann. Don’t know exactly how. Perhaps just flipping through the bins. You can see how a young teenaged boy would be attracted to an album with that cover. Plus: four trumpets! And congas.

The album's title tune, “The Common Ground” is an up-tempo burner that opens with percussion. Mann states the melody on flute, doubled with the vibes, and then the trumpets enter on backing figures, a two bars phrases alternating with punctuations. A percussion break at 1:04 sets things up for Mann’s solo (and, again, the trumpets in the background). Exciting stuff.

This is certainly a different sound from what I’d been used to. Flute? There haven’t been too many jazz flautists. Sax players doubling on flute, yes, but with the flute as the main instrument, no. Hubert Laws played flute as his main instrument, and James Newton. Then there’s Rahsaan Roland Kirk, who was mainly a saxophonist, though that hardly characterizes what he did. He’d frequently play the flute and cut at least one album on flute music–I Talk with the Spirits–and would often hum while playing flute (a trick Ian Anderson took from him).

Just why the flute is not more widely used in jazz, I don’t know. Is it mostly a matter of historical accident, as jazz instrumentation descended from military band instrumentation and flutes aren’t all that prominent there (but then we have the piccolo obbligato in “Stars and Stripes”)? Perhaps it simply wasn’t loud enough to hold its own against brass and sax in the early days (when amplification was poor on non-existent), though the clarinet isn’t that loud either. Maybe it’s just a matter of timbre in the total range. Who knows?

Anyhow, here we have a front line of Herbie Man on flute and Johnny Rae on vibes, an exotic sound in the jazz context (itself exotic in the context of classical strings). I loved it. Talk about exotic, on “Baghdad/Asia Minor” we have another percussion opening – the drums are fundamental, get it? – with Mann on some kind of flute (not the standard transverse flute of European classical tradition) doubled by the arco bass, which is a little different jazz as the double-bass was usually plucked.

Thursday, August 11, 2016

Form, Event, and Text in an Age of Computation

I've put another article online. This is not a working paper. It is a near-final draft of an article I will be submitting for publication once I have had time to let things settle in my mind. I'd appreciate any comments you have. You can download the paper in the usual places:

Abstract: Using fragments of a cognitive network model for Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129 we can distinguish between (1) the mind/brain cognitive system, (2) the text considered merely as a string of verbal or visual signifiers, and (3) the path one’s attention traces through (1) under constraints imposed by (2). To a first approximation that path is consistent with Derek Attridge’s concept of literary form, which I then adapt to Bruno Latour’s distinction between intermediary and mediator. Then we examine the event of Obama’s Eulogy for Clementa Pinckney in light of recent work on synchronized group behavior and neural coordination in groups. A descriptive analysis of Obama’s script reveals that it is a ring-composition and the central section is clearly marked in audience response to Obama’s presentation. I conclude by comparing the Eulogy with Tezuka’s Metropolis and with Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

CONTENTS

Computational Semantics: Model and Text 3

Literary Form, Attridge and Latour 8

Obama’s Pinckney Eulogy as Performance 11

Obama’s Pinckney Eulogy as Text 15

Description in Method 19

Introduction: Form, Event, and Text in an Age of Computation

The conjunction of computation and literature is not so strange as it once was, not in this era of digital humanities. But my sense of the conjunction is a bit different from that prevalent among practitioners of distant reading. They regard computation as a reservoir of tools to be employed in investigating texts, typically a large corpus of texts. That is fine.

But, for whatever reason, digital critics have little or no interest in computation as something one enacts while reading any one of those texts. That is the sense of computation that interests me. As the psychologist Ulric Neisser pointed out four decades ago, it was the idea of computation that drove the so-called cognitive revolution in its early years:

... the activities of the computer itself seemed in some ways akin to cognitive processes. Computers accept information, manipulate symbols, store items in “memory” and retrieve them again, classify inputs, recognize patterns, and so on. Whether they do these things just like people was less important than that they do them at all. The coming of the computer provided a much-needed reassurance that cognitive processes were real; that they could be studied and perhaps understood.

Much of the work in the newer psychologies is conducted in a vocabulary that derives from computing and, in many cases, involves computer simulations of mental processes. Prior to the computer metaphor we populated the mind with sensations, perceptions, concepts, ideas, feelings, drives, desires, signs, Freudian hydraulics, and so forth, but we had no explicit accounts of how these things worked, of how perceptions gave way to concepts, or how desire led to action. The computer metaphor gave us conceptual tools through which we could construct models with differentiated components and processes meshing like, well, clockwork. It gave us a way to objectify our theories.

My purpose in this essay is to recover the concept of computation for thinking about literary processes. For this purpose it is not necessary either to believe or to deny that the brain (with its mind) is a digital computer. There is an obvious sense in which it is not a digital computer: brains are parts of living organisms, digital computers are not. Beyond that, the issue is a philosophical quagmire. I propose only that the idea of computation is a useful heuristic device. Specifically, I propose that it helps us think about and describe literary form in ways we haven’t done before.

First I present a model of computational semantics for Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129. This affords us a distinction between (1) the mind/brain cognitive system, (2) the text considered merely as a string of verbal or visual signifiers, and (3) the path one’s attention traces through (1) under constraints imposed by (2). To a first approximation that path is consistent with Derek Attridge’s concept of literary form, which I adapt to Bruno Latour’s distinction between intermediary and mediator. Then we examine the event of Obama’s Eulogy for Clementa Pinckney in light of recent work on synchronized group behavior and neural coordination in groups. A descriptive analysis of Obama’s script reveals that it is a ring-composition; the central section is clearly marked in the audience’s response to Obama’s presentation. I conclude by comparing the Eulogy with Tezuka’s Metropolis and with Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

Though it might appear that I advocate a scientific approach to literary criticism, that is misleading. I prefer to think of it as speculative engineering. To be sure, engineering, like science, is technical. But engineering is about design and construction, perhaps even Latourian composition. Think of it as reverse-engineering: we’ve got the finished result (a performance, a script) and we examine it to determine how it was made. It is speculative because it must be; our ignorance is too great. The speculative engineer builds a bridge from here to there and only then can we find out if the bridge is able to support sustained investigation.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)