On the one hand we have those simple diagrams Mark Rose drew back in 1972, the ones he apologized for. Why?

Because they’re over the line, ever so slightly. But over, definitely over.

On the other hand, we have these recurring discussions: What is the text? What is the form? They go nowhere, that is, there is no effort to reach consensus on what those things are. On the contrary, these occasions serve to keep the questions alive: Ah, we don’t agree, but that’s OK. Maybe someday they will. Someday.

Someday my ass. The latent purpose of these challenge sessions, if you will, is to make sure that that day never comes. As long as the discipline can continue asking these questions, it can remain blind to its founding shortcomings, the blindness that allows it to pursue interpretation with single-minded vigor.

But what’s that have to do with those poor diagrams of Mark Rose? They blow the whistle on the whole thing. They follow from a simple conception of the text – as a string of words – and a simple conception of form – as the arrangement of items in that string. The profession can’t let such heresy spread!

Let’s take a closer look.

Mark Rose apologizes for simple diagrams

Mark Rose’s slender volume, Shakespearean Design [1], has been on my mind recently off and on for several years as it speaks to two hobby horses of mine, 1) literary form and 2) its description. Rose is interested in Shakespeare’s plays, not interpreting them, telling us what they mean,

This is about an incidental remark in the Preface, something of an apology (p. viii):

A critic attempting to talk concretely about Shakespearean structure has two choices. He can create an artificial language of his own, which has the advantage of precision; or he can make do with whatever words seem most useful at each stage in the argument, which has the advantage of comprehensibility. In general, I have chosen the latter course.

The little charts and diagrams may initially give a false impression. I included these charts only reluctantly, deciding that, inelegant as they are, they provide an economical way of making certain matters clear. The numbers, usually line totals, sprinkled throughout may also give a false impression of exactness. I indicate line totals only to give a rough idea of the general proportions of a particular scene or segment.

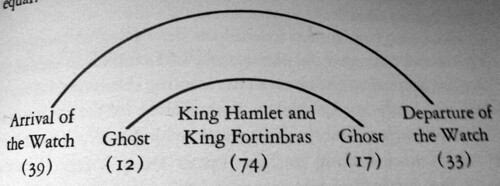

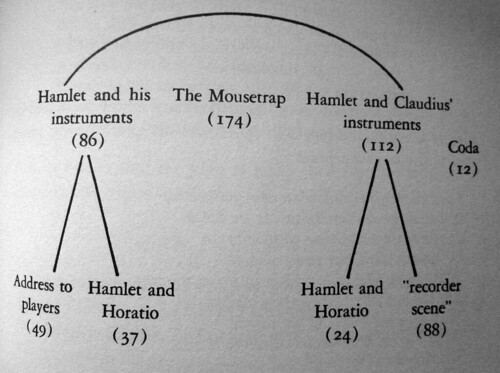

Here’s two of those offending diagrams, from the Hamlet chapter, pages 97 and 103 respectively; you can see the line counts in parentheses:

What’s the fuss about? And there aren’t many of them. These are simple diagrams and, yes, without them, Rose’s accounts would be more difficult to understand. Indeed, without them, a reader would be tempted to sketch their own diagrams on convenient scraps of paper.

I figure Rose’s misgivings about the numbers are about humanistic ideology, we don’t do numbers, though his use of numbers is, as he says, slight. His willies about the diagrams may be that as well, but I think there’s something more there. The diagrams themselves are problematic simply because they ARE diagrams. They intrude too deeply into the inner workings of the humanistic mind. It’s like throwing a spanner into a machine; it gums-up the works.

It’s one thing to have pictures in an illustrated edition of, say, Hamlet, pictures depicting a scene in the play. That’s fine, for it’s consistent with the narrative flow. And it’s fine to have illustrations in, say, an article about the Elizabethan theatre, where you need to depict the stage layout or the relationship between the stage and the seating. Such illustrations are consistent with the ongoing flow of thought.

Those diagrams are different. It’s not that they’re inconsistent with the flow of thought. They’re not. They’re essential to it. But they indicate that this kind of thinking is not quite kosher. Why not? How do these simple diagrams intrude on the humanistic mind, while more elaborate images of the type mentioned in the previous paragraph, while those images are fine?

The problematics of text and form

The concepts of text and form are central to literary criticism. Texts are the things we study and form is what somehow makes them special. And yet we have no consensus views of either concept. In a sense, we don’t know what we’re talking about, though we talk about it incessantly.

The following statement is typical. It is by Frances Ferguson and John Brenkwood introducing papers from the 2013 English Institute on form [2]:

A second irony is that the recently renewed interest in questions of literary form has proved quite amorphous. Perhaps, though, that has been the predicament and vitality of the topic all along. Georg Lukács inaugurated modern literary theory with a collection of essays called Soul and Form, a title that would be impossible today unless it were for a critical reflection on jazz. Among theorists preoccupied with form, there is a recurrent conflict between nonformalist and formalist conceptions of form: Bahktin as against Shklovsky; Jameson as against Frye; or the Barthes of S/Z over against the Barthes of “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative.” There is also a conflict, cutting across these competing methods, between form as a feature of literary works and form as constitutive of literary works. The New critics are often the benchmark of formalism in American discussions, but they did very little to illuminate literary forms compared to the Russian Formalists or, say, Lévi-Strauss and Jakobson’s classic essay on Baudelaire’s “Les chats.” And yet even the surest markers of literary forms fail to define form when it comes to actual works. The form of the sonnet, for example, is readily defined by the number of lines and the stanza organization, but does that account for a particular sonnet’s form any more than a rectangle accounts for a painting’s form? Vertical for portraits, horizontal for landscapes! And, finally, is formalism itself based on the idea that literary works are purely form, or on the idea that the vocation of literary criticism lies in formalization, that is, in its capacity to create categories at a level of abstraction applicable to the widest variety of literary phenomena?

The polarity between Clark’s appeal to human-sensuous activity and Macpherson’s call for a conception of form that holds good even on the assumption of human extinction suggests the philosophical extremities to which the question of form gives rise. So, too, the polarity between the richly historical texture of formal analysis in Jones, Martin, and Butterfield and the radically formalist analysis of Jarvis exemplifies how critical practice, not definition, is where the question of form is most fruitfully fought out.

So, this discipline for which the concept of form is central is still fighting over the concept after how many years? Fifty, a hundred?

It is the same with the concept of text. This is from the introduction Rita Copeland and Frances Ferguson prepared for five essays from the 2012 English Institute devoted to the text [3]:

Yet with the conceptual breadth that has come to characterize notions of text and textuality, literary criticism has found itself at a confluence of disciplines, including linguistics, anthropology, history, politics, and law. Thus, for example, notions of cultural text and social text have placed literary study in productive dialogue with fields in the social sciences. Moreover, text has come to stand for different and often contradictory things: linguistic data for philology; the unfolding “real time” of interaction for sociolinguistics; the problems of copy-text and markup in editorial theory; the objectified written work (“verbal icon”) for New Criticism; in some versions of poststructuralism the horizons of language that overcome the closure of the work; in theater studies the other of performance, ambiguously artifact and event. “Text” has been the subject of venerable traditions of scholarship centered on the establishment and critique of scriptural authority as well as the classical heritage. In the modern world it figures anew in the regulation of intellectual property. Has text become, or was it always, an ideal, immaterial object, a conceptual site for the investigation of knowledge, ownership and propriety, or authority? If so, what then is, or ever was, a “material” text? What institutions, linguistic procedures, commentary forms, and interpretive protocols stabilize text as an object of study? [p. 417]

“Linguistic data” and “copy-text”, they sound like the physical text itself, the rest of them, not so much.

The text as “an ideal, immaterial object, a conceptual site for the investigation of knowledge, ownership and propriety, or authority”, what’s that? It’s where the process of interpretation is said to begin, and that is very elusive indeed.

One might think interpretation begins with the symbols on the page, the “Linguistic data” and “copy-text”, but interpretive criticism cannot begin there because it has no way to get from those bare naked symbols to something it wants to ponder and think about [4]. There’s a transmutation taking place in which symbol becomes thought, and that transmutation is invisible to interpretation. Interpretation starts with thought and endeavors to erase all signs of that transmutation upon which those initial thoughts rest. The physical text itself must be displaced from the arena of interpretation.

Simple concepts of text and form

Physically considered, a literary text is a string of symbols (“Linguistic data”, “copy-text”?) or a sequence of vocal sounds. It may well be and often is both of those things. One speaks the symbols on the page, one commits the vocal sounds to writing. Form then would be the ordering of symbols in the string, the sounds in the speech stream.

And that, in effect, is the conception behind those diagrams that Mark Rose drew, though he never says so in such explicit terms. If you read the diagrams from left to right you follow the order of symbols in the text string. Those diagrams, then, are about the arrangement of those symbols.

What Rose talks about, however, are scenes, and how they mirror one another, counterpoint one another, and so forth. He sometimes uses the figure of a triptych or other painted panels on an alter. So he doesn’t take about the bare naked symbols themselves. He talks about the scenes the carry or support, if you will. But, and this is important, he doesn’t interpret those scenes for us. He describes them in basic terms.

Thus Rose’s critical practice takes place in that transmutation zone between the bare naked symbols and interpretable thoughts. And that, I suspect, is why he finds those diagrams faintly embarrassing. They uncover the existence of that transmutation zone, that liminal space, that allows interpretive criticism to happen and thus threaten to expose its founding self-deception.

They should be embarrassed, but not Mark Rose.

An exercise for the reader

Music is a sequence of sounds, often very complex sounds. When written on a page, music is a string of symbols. Musicologists have developed a rich discourse analyzing the formal structure of music. Why have they been able to analyze musical form while literary critics have, for the most part, neglected the analysis of literary form?

References

[1] Mark Rose, Shakespearean Design, Harvard University Press, 1972.

[2] Frances Ferguson, John Brenkman, Introduction, ELH, Volume 82, No. 2, Summer 2015, pp. 313-318, DOI: 10.1353/elh.2015.0014

[3] Rita Copeland and Frances Ferguson, “Introduction”, ELH, Volume 81, Number 2, Summer 2014, pp. 417-422.

[4] For some thoughts on why that is so, see my earlier post, On the nature of academic literary criticism as an intellectual discipline: text, form, and meaning [where we are now], New Savanna, July 31, 2020, https://new-savanna.blogspot.com/2020/07/on-nature-of-academic-literary.html.

No comments:

Post a Comment