Consider this post an update and amendment to my report, Jersey City: From a Skate Park to the World, and embedded below.

|

| Somewhere behind Mana Museum for Urban Arts on a stanchion supporting the 14th street viaduct, that is, if it's managed to survive all the construction crews that have been mucking around back there. |

With the emergence of Mana Contemporary, Jersey City is set to ride the intersection of two dynamics which could, together, transform Jersey City over the next quarter century. One of these dynamics is about cultural change and growth while the other is about the interaction of culture and urban real estate.

First we talk culture and urban development, and then we discuss Jersey City and Mana Contemporary.

Two Dynamos

One of the best-known dynamics in urban development is the one that begins when artists move in to a dead commercial or industrial neighborhood to get cheap space. The buildings are empty and have large open space well suited for artist’s studios. Services businesses follow the artists – laundries, food stores, restaurants and cafes, and so forth – and then others, with more money to spend on housing, see an upcoming neighborhood and decide to live there. A generation later the artists are priced out of the neighborhood they’d created.

That’s one dynamic. Let’s set that aside for the moment and look at another dynamic, one that’s different and more abstract. This dynamic is about cultural change.

The single best example I can think of is American popular music in the twentieth century, which has been dominated by the interaction between white and black musics. That’s by no means the only dynamic, nor even the only important one, but it’s the one that’s strongest and that’s been doing on the longest, with roots extending back into colonial times.

Thus early in the 20th Century blues and ragtime came bubbling up out of the ground with particular concentrations in New Orleans, Mississippi, Kansas City, and New York City. From this came Swing, the popular music of the 20s, 30s, and into the 40s. Though the most innovative practitioners where black, everyone got in on the act and the audience was mostly white, simply because the white population was and is so much larger than the black. Rock and Roll broke free in the 1950s, first among black musicians and audiences, but then everyone. Hip-hop emerged in the 1980s.

That, of course, is a gross simplification – I run it down in more detail in Music Making History: Africa Meets Europe in the United States of the Blues. The point is simply that we have cultural interaction between two different populations, with different histories and positions in society. A similar dynamic is now operating in the visual arts, and that dynamic is linked to this one in that graffiti is the all-but official visual style of hip-hop.

Graffiti and "Legit" Art

The dynamic relationship between graffiti and the “legit” art world is much like that between black music and white – two-way imitation and borrowing.

Spray-can graffiti arose in New York City and Philadelphia in the late 1960s and early 1970s and had spread around the world by the 1990s–in part because hip-hop took it there. It arose outside the legit art world of galleries, museums, and art schools and maintains a significant “outside” presence to this day. Even the graffiti writers who have gallery representation and have canvases and prints in museum collections insist on maintaining their street cred by doing “illegals.”

It’s the illegal nature of street graffiti that anchors outside the legit art world. And, while some graffiti writers now have art school educations (and may even work as designers with sporting goods, apparel, media and other companies) many writers remain indifferent if not actively hostile to that world. Graffiti has not been assimilated to and absorbed into museum, gallery, and art school culture – though some schools now have studio courses in aerosol art.l

What makes the graffiti/legit dynamic such a powerful one, then, is: 1) graffiti originated outside the legit world and has maintained that status, and 2) graffiti is international, and so has interacted with legit art traditions on every continent. It’s everywhere and remains strong after more than four decades. It’s the most important art form to have emerged in the last half century.

Once graffiti had claimed the streets for (illegal) art, other artists, with different sensibilities and techniques took to the streets. The so-called street artists began gaining prominence in the 1990s. Many of these artists used stencils – Banksy is perhaps the best-known of these – and prints, often quite large, that they pasted on walls. As swing gave birth to bebop, so graffiti gave birth to street art.

Mana Contemporary and the Urban Arts

What does this have to do with Mana Contemporary? Simple. As you know, Mana Contemporary is a multi-faceted arts complex located near Journal Square on the West side of Jersey City. The core business is fine arts storage and handling, with clients including both individual collectors and museums. The complex also has studios for over 200 artists, exhibition space, an outdoor sculpture garden, a foundry, a dance studio, and an auditorium and hotel are planned. That complex is devoted to standard art – though I have seen graffiti in some of the studios and street art in some of the exhibitions.

In September of this year Mana will open the Mana Museum of Urban Arts in a building that’s near the Holland Tunnel about a mile east of the main complex. As the name suggests, this museum will be devoted in graffiti and street art. It may be the first permanent museum devoted to those art forms.

Mana thus has separate institutions devoted to the two poles of this cultural dynamic, the most important one in the visual arts today. It is thus in a position to monitor the further evolution of the dynamic interaction of “legit” art and graffiti/street art.

Will Mana also influence the interaction of these two art worlds? It’s not simply that the Mana complex includes artist’s studios at its main complex and will be sponsoring (as yet unspecified) artist activity at and through the urban arts museum. Because artistic ideas travel freely through various media the mere fact that one institution encompasses and embraces both poles of this cultural dynamic might facilitate and accelerate their interaction.

Could this make Jersey City the epicenter of a 21st Century artistic renaissance? There’s no way to tell.

Mana on the Ground in Jersey City

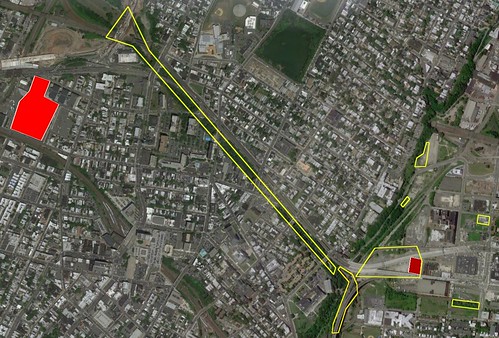

Now let’s look at how this lays out on the ground. The red area at the upper left in the following map is the main campus of Mana Contemporary while the smaller area at the lower right is the building that will house the Mana Museum of Urban Arts:

The areas outlined in yellow are areas where I’ve photographed extensive concentrations of graffiti in the last several years, though some of those areas no longer exist because of construction activities.

The Museum of Urban Arts is located in prime graffiti territory in the “Y” between the 12th and 14th Street viaducts. The stanchions supporting those viaducts have graffiti on their bases, for example:

The building itself has extensive graffiti inside – I’ve not seen it myself, but some writers told me about it – and has graffiti on the outside, naturally. Here’s a pair of rollers high on the rear wall:

Kaws, of course, is the best-known graffiti writer from Jersey City.

Now, look at the map again. The narrow rectangular area at the bottom right marks the Newport Wall, which was featured in The History of American Graffiti (Gastman and Neelon 2011), which is the first major history of American graffiti. The long narrow area extending diagonally through the map is the Bergen Arches, which hardly anyone knows about except urban explorers, homeless people, transportation planners (who want to run a light rail line down there), preservationists (who want to preserve the Arches as a hiking and biking trail), and graffiti writers, who use it as a studio and gallery (see, e.g. my recent post, Me and the Villain, Down by the Arches).

Notice that the Arches more or less run between the two Mana compounds, the main campus near Journal Square and the Urban Arts building near Hamilton Park. Is it possible to walk between the two Mana compounds by going through the Arches, observing the greenery and graffiti along the way? At the moment, no, you can’t do it. Not in any straightforward way, not to mention that you trespass on CSX property when you’re in the Arches.

What about the future? Would it be possible to make a path between the two? Well, the answer to that depends on your sense of possibility. In the normal order of things, which is pretty much where we are now, no, it would not be possible. It would cost too much, but more to the point, it would take too much civic will and imagination.

Assume, however, that Jersey City’s governmental, educational, philanthropic, and business leaders have the requisite imagination and are willing to work with the citizenry to forge the civic will, what could we do?

A Path from Mana to Mana

Here’s what I have in mind:

The white line marks a path that leads from the Urban Arts building at the lower right, through the Bergen Arches, and over to the Mana main campus. The path is about a mile and a half long.

Getting from the Urban Arts building to the Arches is relatively straightforward. Getting from the west end of the arches to main Mana campus is not.

Getting from the Urban Arts building to the Arches is relatively straightforward. Getting from the west end of the arches to main Mana campus is not.

Why? The Pulaski Skyway, that’s why:

The buildings in the background are part of the American Can Company complex. Three of the buildings have been converted into residences, the Canco Lofts. The two in the photo belong to Mana Contemporary. That roadway in front of them is the Pulaski Skyway. Given the location of the Bergen Arches you have to go over the Skyway to get to Mana Contemporary – or under it.

Let’s return to the map. That green area at the upper left is a three-acre plot of vacant land next to St. Peter’s Cemetary, which is the oldest Catholic cemetery in Jersey City. An associate of mine has suggested that that plot of land be turned into a park: a skate park, or a sculpture park, but why not both? It’s easy to walk through the Arches, which exit beneath J. F. Kennedy Boulevard, and the under Tonnele Ave., as the Green Villain is about to do...

... and then go up the embankment, which brings you here:

The vacant lot is to our right and the cemetery is in front of us, also stretching to the right. That’s Mana Contemporary peeking over the trees in front of us. To get there we have to either build a bridge, or perhaps a tunnel.

My current thought is to build a low observation tower in the park and extend the bridge to it. People could hang out on the tower and look out over the Meadowlands to Northwest, the Hackensack River to the West, and Jersey City everywhere else, with glimpses of New York City to the East. At night the views would be spectacular.

My current thought is to build a low observation tower in the park and extend the bridge to it. People could hang out on the tower and look out over the Meadowlands to Northwest, the Hackensack River to the West, and Jersey City everywhere else, with glimpses of New York City to the East. At night the views would be spectacular.

Practical? No, probably not.

But we’re not being practical. We’re dreaming, dreaming of Jersey City that’s an international hub – $90 million or more a year in tourist revenue; see the report – of artistic activity.

* * * * *

* * * * *

This is post 2499. The next one will be 2500.

No comments:

Post a Comment