Note: This may be the most important post in the series. But it’s a long way through, 6000 words or so. Fortunately, there are a lot of illustrations, and much of the argument is in those illustrations.

This will concludes my examination of the “Theme” chapter from Matthew Jockers, Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History. First I say a word or three about topic modeling. Then I review Jockers’ own findings. Then I ride one of my current hobby horses, Leslie Fiedler’s argument in Love and Death in the American Novel. First I look the waxing and waning of themes through the 19th century and then I return to Moby Dick and move on briefly to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. I conclude with some informal remarks about argument, evidence, epistemology, and interface design.

Operationalizing the Idea of Theme

When I was originally thinking about this post I decided that, since I’d already explained topic modeling elsewhere (e.g. HERE), there was no point in doing it again. But I’ve now decided to do it again just to make the point that we’re operating in an “operationalized” intellectual world and we must be aware of that.

For example, while Jockers has identified 500 themes (a term in ordinary language) in his corpus of 3346 novels, it would be somewhere between misleading and outright mistaken to say that he discovered 500 themes. For that would imply that it could have been 386 or 617 or 239 or any other number of themes, but that, no, it turns out that there are 500 of them, no more, no less.

Jockers has 500 themes because he ‘instructed’ his algorithm to prepare that many. He could have instructed it to prepare any number of topics (a term of art in corpus linguistics) he wished, 386, 617, or 239, for example. There’s no discovery involved. What’s involved is more like tuning. Jockers explored various possibilities and 500 seemed like a useful number of topics.

What’s going on?

Topic analysis depends on the fact that the words used to state some theme are going to occur together in any text where that theme shows up. It’s all about context. That fact isn’t of much use if you’re dealing with only a handful of themes in a small body of text. But if you’ve got a large body of texts with an appreciable number of themes, then there’s a way you can get a computer to list the words in each theme, more or less.

If a given text doesn’t contain a given topic then the words associated with that topic won’t appear in that text, obviously. Oh, some of them might, but not all of them. So, the computer does a massive comparison of the words that occur throughout the corpus. Just how it does this is irrelevant at the moment, as least, it’s irrelevant if you’re willing to trust that the researchers who invented the technique know what they’re doing. One interesting thing about the technique is that the results improve as the corpus gets larger–assuming you’ve got the computer power needed to crunch the data. That’s because a larger corpus will have a larger number of topics and each different topic will appear in contrast to a larger universe of topics. It’s the contrast that the computer’s looking for.

But, as I’ve said above, in order to run the algorithm, you’ve got to specify how many topics you’re looking for. If the number is too high the algorithm returns (p. 128)

topics lacking enough contextual markers to provide a clear sense of how the topic is being expressed in the text; setting the number too low may result in topics of such a general nature that they tend to occur throughout the entire corpus.

But you don’t necessarily want to run your algorithm against the entire text as a single analytical unit if the texts are individually large, as is the case with novels. What happens then is that just about any topic can be found in a given text. Jockers determined that he needed to slice his texts into 1000 word chunks. That is, each whole novel is searched, but the algorithm treats each 1000-word segment of a novel as an independent text for the purpose of determining word co-occurrence.

This has the benefit that it is possible to track the distribution of a given topic in a novel (Jockers gives examples on pp. 142-43). Thus topic modeling returns useful results both at the macro scale of the whole corpus and the meso scale of the individual text (on scales, see Reading Macroanalysis 5: An Interlude on Scale: Micro, Meso, and Macro in this series).

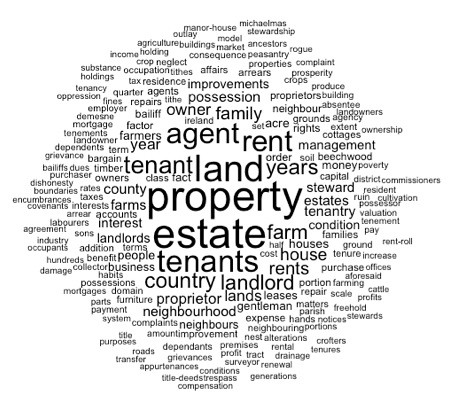

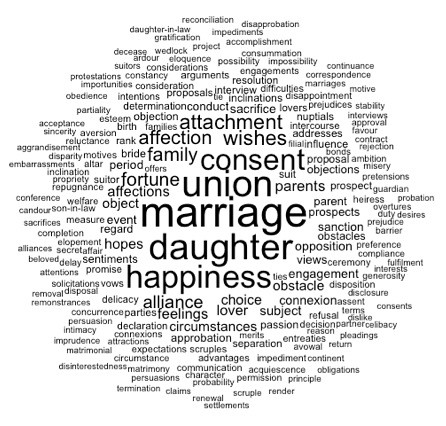

What the algorithm returns for each topic is a weighted list of words for that topic, where the weighting of a word is proportional to its frequency in the topic. Jockers’ preferred representation for a topic is a word cloud, such as this one:

But it’s not convenient to use those clouds as devices for referring to a given topic. For that purpose it’s useful to have names. The general practice is to devise a name from the words most prominent in the topic. Thus, Jockers has called that topic TENANTS AND LANDLORDS.

And when he refers to a topic, it’s to that weighted list of words he’s referring, because that’s the operationalized object. Topic modeling is useful because the operational objects defined by the technique have a useful correspondence to the ‘natural’ topic, in this case, the discourse of tenants and landlords.

The Corpus

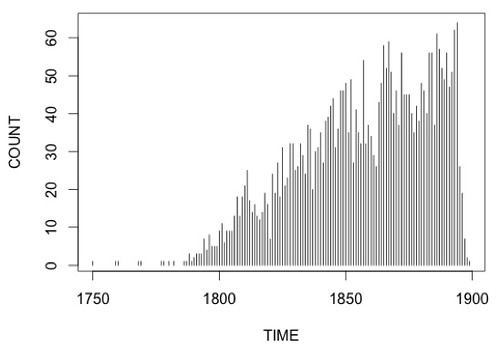

There’s one more thing we’ve got to note before getting down to business. Jockers’ corpus includes 3,346 American, British, Irish, and Scottish novels published between 1750 and 1899. But the distribution of texts across that span is by no means full and even. Here’s a chart that depicts the distribution of texts by year of publication (from Jockers and Mimno, “Significant Themes in 19th-Century Literature,” Poetics 41 (6), 2013, 750-769, available in an online preprint):

It isn’t until well into the 19th century that we see 20 or more books per year in the corpus. Since we’ll be taking particular note of the temporal unfolding of themes we should keep this in mind. At least some of the erratic action at the 18th century end of the distribution is likely the result of a small sample size. This particularly effects American novels which were few and far between in the 18th century.

Jockers’ Findings

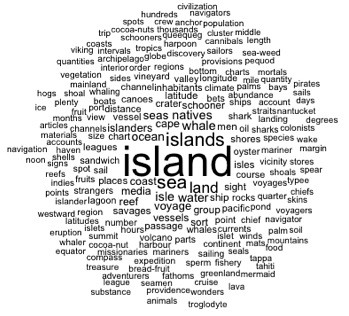

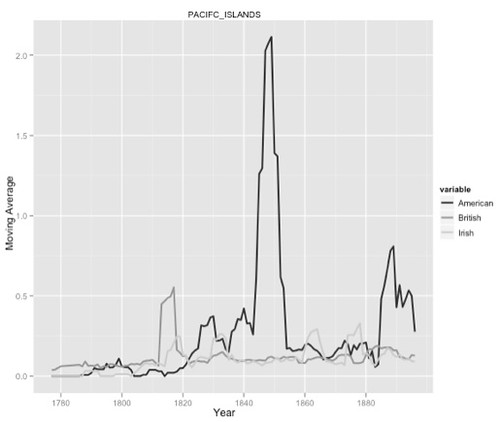

Jockers begins unpacking his results by looking at Moby Dick. He lists the ten most prevalent themes in that novel, noting that they are relatively rare in the corpus as a whole. The most prominent theme is, not surprisingly, Seas and Whaling (called PACIFC ISLANDS AKA SEAS AND WHALING on the pull-down menu for the online topic browser):

It takes up almost 20% of the book, but less than 1% of the whole corpus. Then we have SHIPS at about 7%, BOATS AND THEIR CREWS, 2.5% and others, both less than 1% in the whole corpus (chart, p. 132).

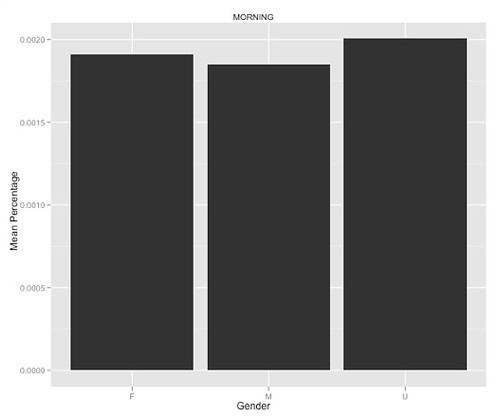

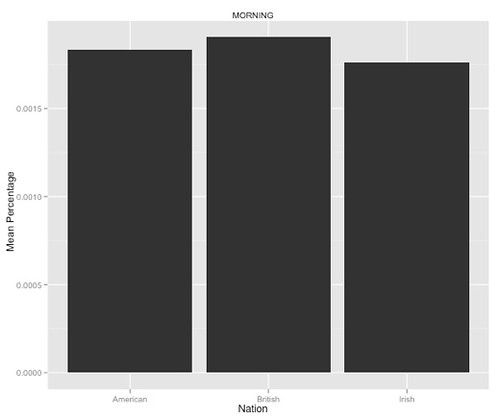

The theme MORNING is one of the most prevalent in the entire corpus and it is present in Moby Dick at roughly the same magnitude as in the whole corpus (0.25%). Notice that MORNING occurs evenly across author gender (M, F, and U, for unknown) and nation (American, British, Irish):

Gender

Nation

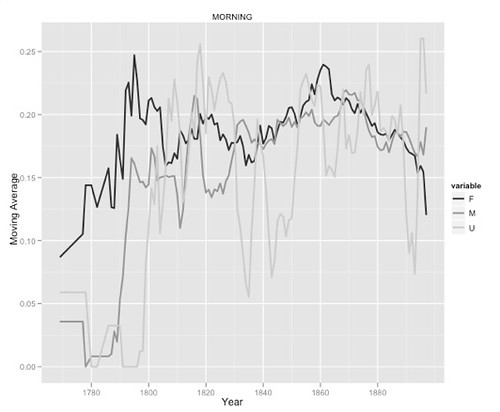

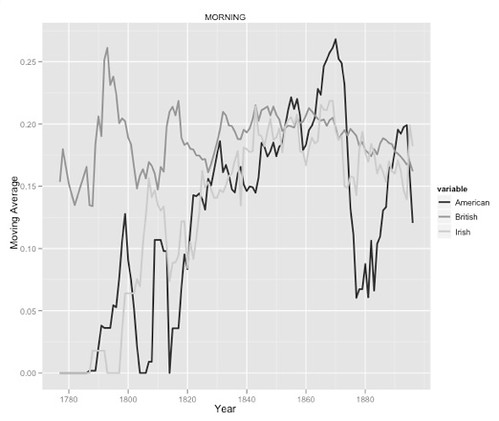

The next two charts show its distribution according to gender and nation over time:

Gender by Year

Gender by Nation by Year

The gender distribution is pretty erratic before 1800 for males and undecided, but not so much for females. The national distribution is pretty erratic before 1820 for Irish and American texts, but not for British–but notice the dip for American texts around 1880.

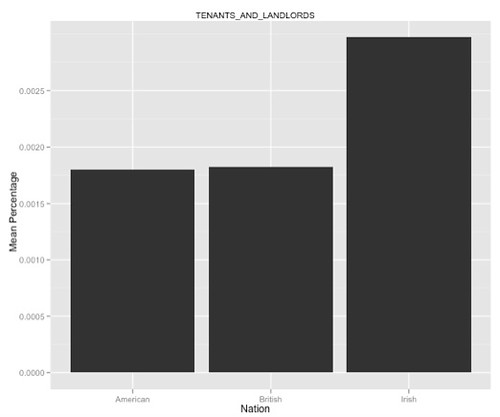

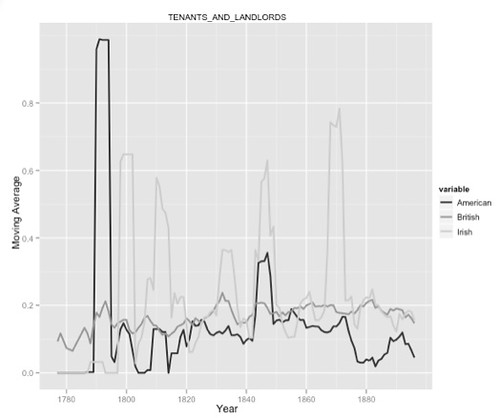

Jockers then goes on to discuss thematic preferences among nations and genders. As Irish literature is his particular interest, that’s what gets the most attention. One theme which is particularly important in Irish literature is LANDLORDS AND TENANTS:

Let’s look at the distribution of this topic over time (the Irish curve is light gray):

Forget the portion of the curves before 1800 (Jockers doesn’t even show them in the book). Jockers attributes the first spike to, c. 1810, to Castle Rackrent and Wild Irish Girl; he says nothing about the second one (c. 1835), but notes that the third corresponds to the Great Famine of 1845 and after.

The spike of the 1849s is followed by a steep decline into a trough that runs from the 1850s until the late 1960s. Such a decline may very well be attributable to the aftermath of the famine. This was, after all, a national catastrophe that would have made writing fiction about strained tenant-landlord relationships seem almost cruel and unusual punishment for a devastated population. A final spike of increased writing about tenants and landlords is seen in the 1860s, where again it seems to have parallel currency in the American context. (p. 144)

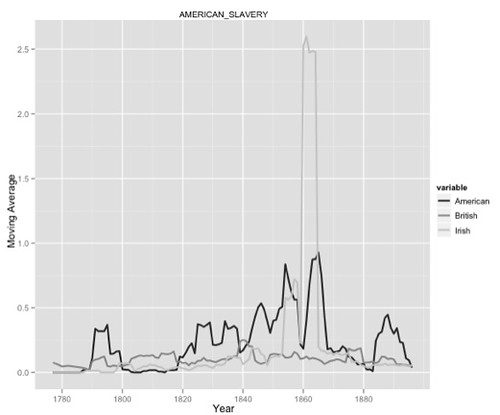

Jockers then goes on to point out that, while the AMERICAN SLAVERY topic is most prominent in American texts, it is roughly twice as prevalent in Irish as in British texts and has a peak during the American Civil War:

He attributes that peak to Mayne Reid, a prolific author who published a well-known anti-slavery novel, The Quadroon, in 1856.

Jockers then discusses experiments in predicting author nationality, gender, and date of publication on the basis of thematic ‘signals.’ That can be done with about 67% accuracy. The topics that proved most useful in separating national literatures are those involving features of national dialect. Those aren’t themes or topics in the ordinary sense of the terms, but they are coherent groups of words that will co-occur in texts.

Jockers concludes by mentioning themes which are particularly important in the national literatures (we’ll see a bit of this in the next section) and, finally, shows that the (pp. 151-153)

gender data from this corpus area ringing confirmation of virtually all of our stereotypes about gender. Smack at the top of the list of themes most indicative of female authorship is “Female Fashion.” “Fashion” is followed by “Childrenb,” “Flowers,” “Sewing,” and a series of themes associated with strong emotions... In contrast stand the male authors with their weapons and war. Topping the list of characteristic themes for men is “Pistols,” followed in turn by “Guns,” “Swords,” “Weapons,” “Combat,” and a series of themes related to the rugged masculine places where such implements of war are most likely to be employed...

And so it goes, as Kurt Vonnegut would say.

Waxing and Waning of Themes

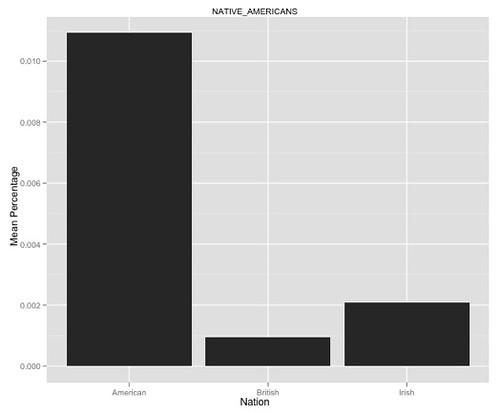

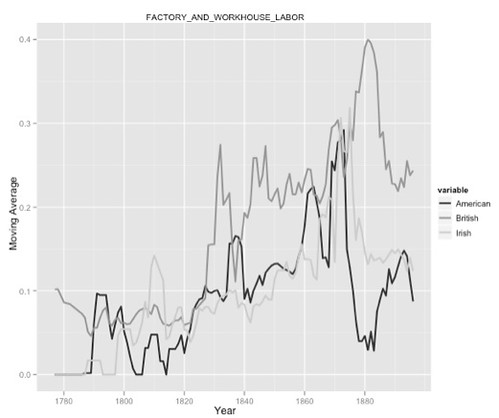

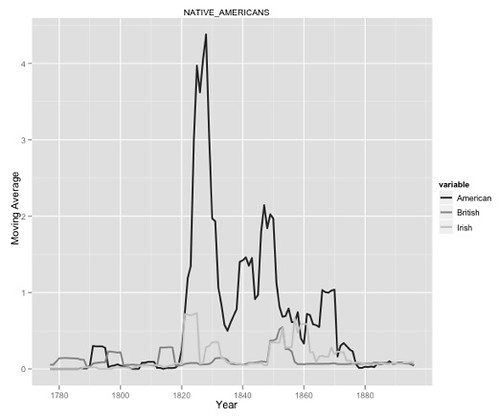

As I said at the outset, what interests me is the waxing and waning of themes over time. We’ve already seen a bit of that in the previous discussion (for MORNING, LANDLORDS AND TENANTS, and AMERICAN SLAVERY). Let’s consider two more themes, FACTORY AND WORKHOUSE LABOR and NATIVE AMERICANS. The next two charts depict the occurrence of these themes by nation:

FACTORY AND WORKHOUSE LABOR by Nation

NATIVE AMERICANS by Nation

Note that NATIVE AMERICANS is of far more interest to Americans than it is for the British and Irish, but that FACTORY AND WORKHOUSE LABOR is of greater interest to the British than the Irish. These distributions make sense on general historical grounds. Native Americans were a direct concern of Americans, of course, but not for the other two. Similarly, Britain was more industrialized in the 19th century than America or Ireland.

Let’s look at how these themes perform over time. First FACTORY AND WORKHOUSE LABOR by nation and year:

Given the time course of industrialization, the general rise of these topics over time makes sense, though the late century parallel drop for both the Irish and the American curves needs some account.

The time course for NATIVE AMERICANS also makes general sense:

The topic is of little interest to the British and Irish so those curves scurry along at the bottom of the chart. The American curve goes high after 1820 (The Last of the Mohicans was published in 1826) and then spikes generally downward over the course of the century. Conflict with Native Americans continued through the century (the Wounded Knee Massacre happened in 1890) but it shifted westward as European Americans settled the continent. During the second half of the century it was no longer of direct concern east of the Mississippi and so was less salient in the national imagination, such as FACTORY AND WORKHOUSE LABOR (except for that dip around 1880).

As just-so stories, these seem reasonable enough. And that’s all they are, just-so stories. The point is simply that literature does track large-scale trends and events in the world, such as industrialization, European settlement, the Great Famine, or American slavery.

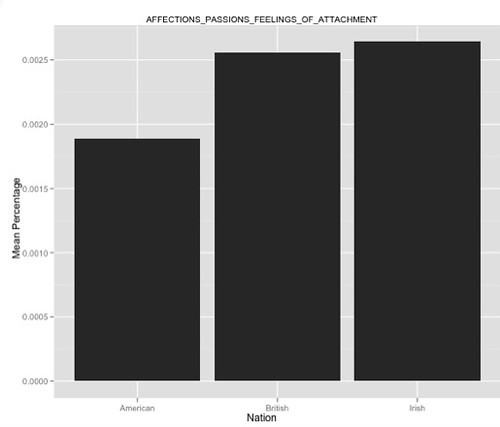

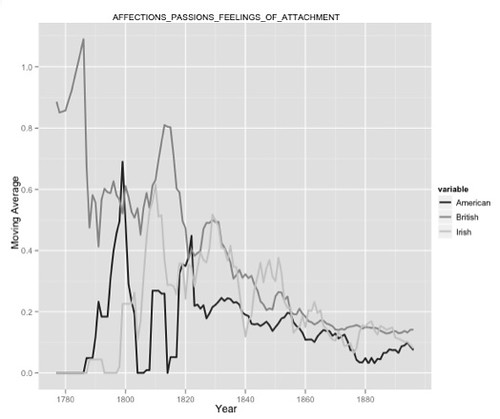

Now let us look at a different set of topics, having to do with feelings and marriage. This shows the distribution of AFFECTION FEELINGS OF ATTACHMENT by nation:

This topic is of more interest to the Europeans, that is, the British and Irish, than to Americans. The difference isn’t all that large, but it is in the direction Love and Death in the American Novel would lead us to expect. Here’s the time-course of this topic:

It’s basically downward from the beginning of the century through the end. Notice that it starts high for the British curve (before 1780) and drops. The British novel arose in the second quarter of the 18th century and took marriage and romance as its central themes. As for the crazy performance early in the American curve, the American novel lagged the British by about half and century and, remember, our sample of texts is pretty poor before the second quarter of the 19th century.

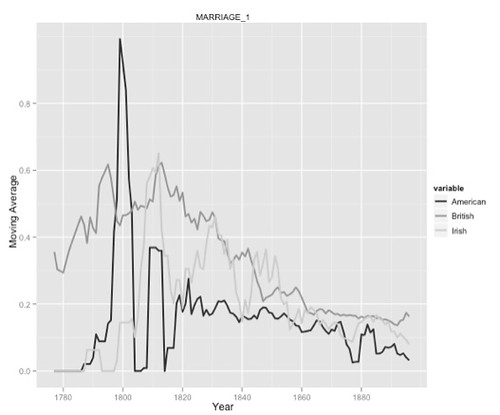

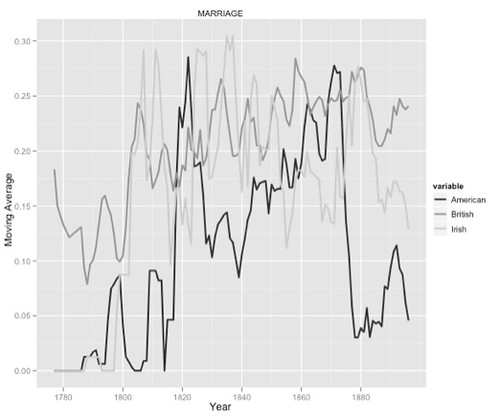

Look at these curves for MARRIAGE 1.

They’re much like those for AFFECTION FEELINGS OF ATTACHMENT. They start high and descend through the end of the century.

In contrast, the curves for MARRIAGE perform differently:

They’re more or less high during the middle of the century and low at the beginning and the end. What gives?

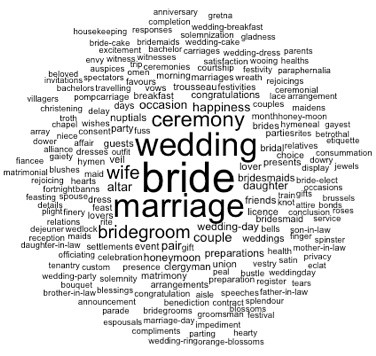

Let’s look at the word clouds, MARRIAGE 1 first, and then MARRIAGE:

MARRIAGE 1 Word Cloud

MARRIAGE Word Cloud

Notice the prominence of daughter and consent in the cloud for MARRIAGE 1, which are not at all prominent in the other one (if they’re there at all; I’ve not attempted to read the whole thing). MARRIAGE 1 looks rather like a Jane Austen topic, with parents concerned for dear daughter, while MARRIAGE is a bit different. The different time course of these two sets of curves seems to correspond to a change in the conception of marriage.

Parental wishes and arrangements were still of imaginative concern early in the century. But that shifted as more and more marriage was conceived of as a relationship between the couple, rather than a quasi-economic arrangement between two families. In practice parents may still have been concerned with the marital fates of their children, and so took whatever hand in those matters they could. But imaginatively, things had changed.

It’s not at all clear to me that in this case literature is tracking events and trends external to it in the way it was for industrialization or relations with Native Americans. There is an extensive body of literary criticism about love and marriage. One conclusion a person might draw from that literature is that European literature played a major role in bringing people to reconceive the nature of personal interactions between men and women. Literary culture is thus not external to family and marital culture and so merely reflecting on it. Rather literature stands in a dialectical relationship–if I may use such a term–to marital culture and so plays a causal role in that culture. It is a means though which people imagine new possibilities for their interpersonal relationships.

This is certainly not the place to attempt a summary of that evidence. Suffice it to say that that is my own position in the matter (see e.g. this paper on Shakespeare and his importance in conceptualizing the family and this one, The Evolution of Narrative and the Self). Yes, literary culture does track external events, it does “reflect.” But it also influences and determines attitudes and practices. Jockers’ topic models contain information that’s useful in considering these questions.

What Then of Moby Dick?

As Jockers points out in this chapter (p. 131), and as I emphasized in an earlier post (Reading Macroanalysis 6.2: Theme, Moby Dick in the Context of Literary Culture), Moby Dick is an outlier, a monster, a sport. It was a failure in its time. And was, and also is, a great book.

Where did it come from? Was it one of those texts that reflects the external world? To be sure, the American whaling industry was the largest in the world (though it would be scuttled by the discovery of oil in Eastern Pennsylvania a decade after the book was published) and was important in the nation’s economy. But Moby Dick came out of nowhere. The most important topic in the book, PACIFC ISLANDS AKA SEAS AND WHALING, was not at all prominent before Moby Dick was published:

Whatever Melville was doing, he was not following a rising trend in the literary world nor was he responding to external events. It was the product of his imagination, an imagination that enjoyed a substantial degree of autonomy with respect to the world around him.

And, as Leslie Fiedler pointed out a half-century ago, that book sets sail with an affectionate “marriage” between two men. This marriage was not, so far as the novel tells, a sexual one. But it was substantial and it was physical.

But those were not merely two men. One was of European descent while the other was a “savage” from the South Pacific. The crew of the Pequod also included African Americans, Native Americans, and a Middle Easterner (Fedallah, the Parsee). In this respect the crew reflected a transnational and multi-ethnic Atlantic world of seamen operating out of ports along both sides of the Atlantic and in both the northern and southern hemispheres (see Ira Berlin, “Societies with Slaves: The Charter Generations,” Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America, Harvard University Press, 1998).

Consider, for example, this passage from Chapter 27, “Knights and Squires” (Note: I’m using the Project Gutenberg text):

As for the residue of the Pequod's company, be it said, that at the present day not one in two of the many thousand men before the mast employed in the American whale fishery, are Americans born, though pretty nearly all the officers are. Herein it is the same with the American whale fishery as with the American army and military and merchant navies, and the engineering forces employed in the construction of the American Canals and Railroads. The same, I say, because in all these cases the native American liberally provides the brains, the rest of the world as generously supplying the muscles. No small number of these whaling seamen belong to the Azores, where the outward bound Nantucket whalers frequently touch to augment their crews from the hardy peasants of those rocky shores. In like manner, the Greenland whalers sailing out of Hull or London, put in at the Shetland Islands, to receive the full complement of their crew. Upon the passage homewards, they drop them there again. How it is, there is no telling, but Islanders seem to make the best whalemen. They were nearly all Islanders in the Pequod, ISOLATOES too, I call such, not acknowledging the common continent of men, but each ISOLATO living on a separate continent of his own. Yet now, federated along one keel, what a set these Isolatoes were! An Anacharsis Clootz deputation from all the isles of the sea, and all the ends of the earth, accompanying Old Ahab in the Pequod to lay the world's grievances before that bar from which not very many of them ever come back. Black Little Pip–he never did–oh, no! he went before. Poor Alabama boy! On the grim Pequod's forecastle, ye shall ere long see him, beating his tambourine; prelusive of the eternal time, when sent for, to the great quarter-deck on high, he was bid strike in with angels, and beat his tambourine in glory; called a coward here, hailed a hero there!

And then there is the extraordinary conversation, broken with song and dance, among the harpooners and sailors that Melville sets out in Chapter 40, “Midnight, Forecastle.” Here’s the list of speakers, more or less, in order, of appearance:

1st Nantucket Sailor, 2nd Nantucket Sailor, Dutch Sailor, French Sailor, French Sailor, Iceland Sailor, Maltese Sailor, Sicilian Sailor, Long-Island Sailor, Azore Sailor, China Sailor, French Sailor, Tashtego, Old Manx Sailor, 3rd Nantucket Sailor, Lascar Sailor, Tahitan Sailor, Portuguese Sailor, Danish Sailor, 4th Nantucket Sailor, English Sailor, Daggoo, Spanish Sailor, St. Jago's Sailor, 5th Nantucket Sailor, Belfast Sailor.

That’s a veritable united nations of a crew. Now, Melville wasn’t attempting to depict the ship as a utopian democracy of nations. It’s quite clear that the captain ruled the ship–in this case a captain mad as Hamlet, albeit madness of a different kind–and that the officers were all white men. It’s the crew that’s polygot.

Melville of course was not the first American novelist to pair whites and non-whites; we’ve got James Fennimore Cooper’s pairing of Natty Bumppo and Chingachgook in five novels published in the second quarter of the century. But, by setting his tale on the sea and thus free of the land, Melville emphasized the community of men–for, as Fiedler insisted, it was men–in a way that Cooper did not.

So, here’s what I’m wondering: Even though Moby Dick was a popular flop, did Melville set a crucial precedent for later writers? What I have in mind, to shift gears just a bit, is the argument that Ernst Gombrich made in Art and Illusion about the development of realistic depiction in Western art from the Renaissance through the end of the 19th century. His point was simple: artists didn’t just look at the world and draw or paint what they say as though to do so were the most natural thing in the world. Rather, techniques must be invented for solving the many problems posed by realistic depiction. Those techniques were invented generation-by-generation and accumulated in the European aesthetic tradition.

So too it must be with prose fiction, no? In short, to cut right to the chase, if Melville hadn’t figured out how to depict affection between two men of different races and background, Ishmael and Queequeg, Mark Twain would have been unable to tell his story about Huck and Jim. Huck treats Jim as a black mammy who soothes the wounds inflicted by his abusive alcoholic father and constricting mother-surrogate (Aunt Sally). In Jim Huck finds the nurturing parent he so desperately needed, prompting Fiedler to remark that Jim gives Huck (Love and Death in the American Novel, p. 353):

...pure affection...without the threat of marriage... the protection and petting offered by his volunteer foster-mothers without the threat of pious conformity...the friendship offered by Tom without the everlasting rhetoric and make-believe. Jim is all things to him: father and mother and playmate and beloved...calling Huck by the names appropriate to their multiform relationship: “Huck” or “honey” or “chile” or “boss,” and just once “white genlman.”

That is an extraordinary statement, but it is true. At the very heart of American literature we have this story of a dispossessed white boy who finds his deepest emotional satisfaction in the bosom a black man. For the first time in his life Huck feels at home, on a raft in the Mississippi with an escaped slave standing in for his parents. Huck and Jim on that raft in the Mississippi are tropological descendants of Ishmael floating to life on Queequeg’s coffin.

We find none of that, of course, in Jockers’ charts. That requires that the critic read the books, know a thing or three about cultural history, and know how to apply that knowledge to the task. What we do find in Jockers’ charts is that one chart (reproduced above) that makes the originality of Moby Dick quite clear. And it establishes that originality, not simply with respect to the canon, but with respect to the much larger group of texts in Jockers’ corpus.

That chart, and the others, gives us a new foundation on which to make our arguments, whether we refit existing arguments, as I have been doing with Leslie Fiedler’s argument in Love and Death in the American Novel, or embark on new ones, ones we couldn’t even have imagined without knowledge of the patterns revealed in this data.

What Have We Got?

The arguments I’ve been presenting about literary history are pro forma arguments. I believe the points I am arguing, but my belief in them precedes these arguments. The point of these arguments is to demonstrate that we now have a new kind of evidence to bring use in our thinking.

I don’t know what REAL arguments using this evidence would look like. I cherry-picked my charts, and discussed the particulars of only one text. I offered these arguments in the spirit of the term paper assigned in a social theory class I took at Johns Hopkins and taught by Arthur Stinchcombe. It was one of those courses open both to upper division undergraduates and beginning graduate students. For our final project we had to 1) pick some social phenomenon; 2) provide a theory or model to account for that phenomenon; and 3) list three consequences of that theory that could be detected by empirical means. The phenomenon we choose could be real or imagined. Stinchcombe didn’t care which; he just wanted to see how we reasoned.

I cannot imagine what it would be to deploy the full force of that evidence. We need new epistemologies to go along with these new kinds of evidence. Consider this paragraph from Alan Liu’s recent essay, Theses on the Epistemology of the Digital: Advice For the Cambridge Centre for Digital Knowledge:

But alluding to the Enlightenment forecloses as much as it discloses. An honest effort to grapple with digital knowledge will also require the Centre for Digital Knowledge to let go of too fixed an adherence to established modern ideas of knowledge (here simplistically branded “Enlightenment”). Those ideas are bound up with philosophical, media-specific (print, codex), institutional (academic and other expert-faculty), and “public sphere” configurations of knowledge that co-evolved as the modern system of knowledge. But today there are new systems, forms, and standards of knowledge, including some that refute or make unrecognizable each of the modern configurations mentioned above–e.g., algorithmic instead of philosophical knowledge, multimedia instead of print-codex knowledge, autodidactic or crowdsourced instead of institutional knowledge, and paradoxically “open”/”private” (even encrypted) instead of public-sphere knowledge.

And Liu’s is just getting warmed up at that point.

Aside from high epistemology, there is the mundane business of keeping track of your materials. I felt almost as though I have been drowning in evidence that is too complex for me to organize–I downloaded many charts that I have not used in any of these posts. In order to survey those charts I used the Icon view option of the Mac OS X interface, thus:

But that was no more than a poor workaround.

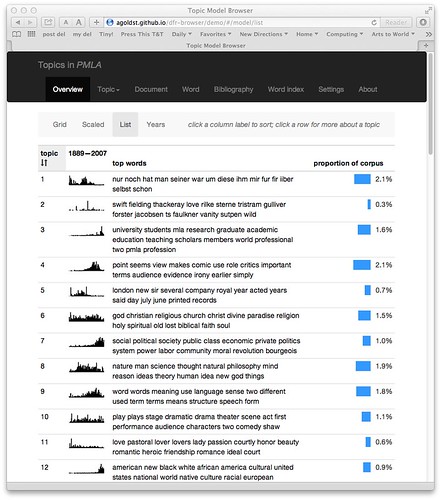

Going forward we need to explore interface design. Work like that that Andrew Goldstone has done in connection with the article he co-authored with Ted Underwood, The Quiet Transformations of Literary Studies (preprint PDF), is critical. You can read his thoughts about interface design HERE; you can access that interface HERE. Here is one of the displays he’s constructed:

Along the left you see a thumbnail sketch of the temporal distribution of each topic. When that distribution is the central focus of your argument, as has been the case for me, that’s what you want to know before investigating that topic further. The middle column lists some of the words in the topic while the right hand column shows the prevalence of that topic in the corpus.

And that’s only one of the displays Goldstone has constructed. You should examine them all.

At the moment I’m thinking that it would sure be nice to access Jockers’ corpus though Goldstone’s interface. But that won’t quite do as Goldstone doesn’t have provisions for viewing patterns segregated by the gender and nationality of the authors. In line with my general belief that there is no such thing as a 15-minute job I’m guessing that, just as porting Jockers’ database to Goldstone’s interface as is would be a chore and a half, so modifying Goldstone’s interface to accommodate the kind of displays Jockers’ has used will have hidden challenges.

This has nothing to do with issues of high epistemology and truth, but we cannot even get to high epistemology without dealing with interface issues. You can’t make an argument if you can’t see the patterns which are your primary evidence.

Thus, when I was working on this post, I first thought things through by looking at topics though Jockers’ online browser and taking screen shots of any images I thought I might use. When I’d thought things through to the point where I was ready to begin writing, the first thing I did was to create a simple topic outline with some stray notes here and there. Then I selected the charts I wanted to use and put them into the document in the order I wanted to use them. Only then did I start writing my prose.

Visualization is practical epistemology.

Are we there yet?

* * * * *

I expect to write three more posts in this series, though that, of course, is subject to change. One post, which I’ve already started, will comment on a passage from Tim Morton’s Hyperobjects. I’ll then write a concluding post in which I talk about recasting this enterprise in terms of cultural evolution where texts are phenotypic objects, genres are species-like, and words are gene-like; topics then are bundles of gene-like entities that tend to occur together in texts (phenotypic entities). Finally, I’ll tie the whole pile together and write a general introduction.

At least that’s the plan.

* * * * *

Previously:

- Reading Macroanalysis 1: Framing: Hyperobjects, Objectification, and Evolution

- Reading Macroanalysis 2: Metadata and the Emperor’s New Clothes

- Reading Macroanalysis 2.1: How do we make inferences from patterns in collections of books to patterns in populations of readers?

- Reading Macroanalysis 3.0: Style, or the Author Comes Back from the Dead

- Reading Macroanalysis 3.1: Style, or Measuring the Autonomous Aesthetic Realm

- Reading Macroanalysis 4: On the matter of “the”

- Reading Macroanalysis 5: An Interlude on Scale: Micro, Meso, and Macro

- Reading Macroanalysis 6.1: Theme–Dogs, Gold, Slavery, and Awakening

- Reading Macroanalysis 6.2: Theme, Moby Dick in the Context of Literary Culture

- Reading Macroanalysis 6.3: DOGS and BIRDS, or, the hermeneutics of screwing around

- Reading Macroanalysis 7: Influence, or the evolving dynamic integrity of the aesthetic sphere

- Reading Macroanalysis 7.1: Visualizing the Geist of 19th Century Anglo-American Literary Culture

No comments:

Post a Comment