In this post, which is a long one, I use two books to investigate Jockers’ themes, and vice versa. One of the books is a classic of fairly traditional, at least by now, literary criticism, Leslie Fiedler’s Love and Death in the American Novel. The other book is one that Fiedler examined, Herman Melville’s Moby Dick.

First I open with some of Jockers' charts, then I consider a particular passage from Moby Dick, and Fiedler’s gloss on it. I then return to Jockers, looking for themes and charts that resonate with or respond to the passage. What I’m up to is, in effect, using Fiedler to guide me in a close reading of Jockers’ distant reading, a term, by the way, that he doesn’t use. I’m using it, of course, for rhetorical purposes.

Note: I downloaded all the charts from Matt Jockers’ Macroanalysis website.

An Outlier in the 19th Century

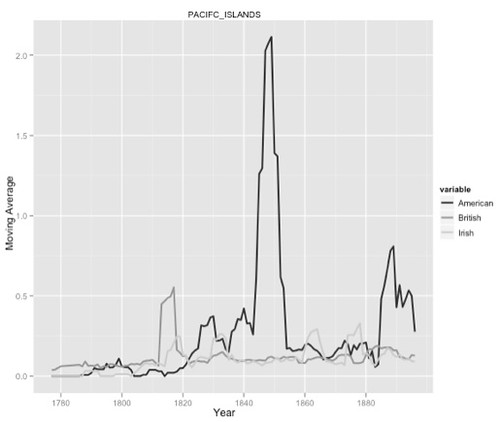

Look at this graph:

That spike in the middle is Moby Dick. Not literally of course. But it is reasonable to believe that that spike in the data is caused mostly by Moby Dick–where cause is to be read as Aristotelian formal cause. The timing is right; Moby Dick was published in 1851, which is roughly where that spike peaks. The light grey line shows the use of the topic by Irish authors in the 19th century; the darker grey line shows use by British authors. And the black line, of course shows American authors.

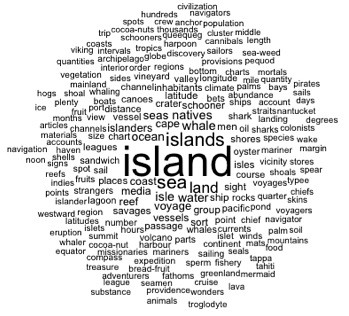

And the topic is typical of Moby Dick. In his book Jockers calls it Seas and Whaling; on his website it’s PACIFC ISLANDS AKA SEAS AND WHALING. Here’s the corresponding word cloud:

Above island and islands in the middle you can see whale while near the top in the middle you can see Queequeg.

Note: for reasons that Jockers explains in the book, proper names are generally eliminated from topic models because they can recur in many contexts without there being any thematic similarity between those contexts; this one slipped through.

This particular topic constitutes almost 20% of the text of Moby Dick, though it constitutes a very small faction of the corpus as a whole (p. 130 and Figure 8.4 p. 132). Other topics having to do with ships and the sea are also prominent in the book while being relatively unimportant in the whole corpus of 3.346 British, American, and Irish novels.

Moby Dick is, as Jockers says, an outlier. It is also one of the world’s great novels. Back in 1976 Edward Mendelson included it as one in a very small and exclusive genre he called the encyclopedic narrative (“Encyclopedic Narrative: From Dante to Pynchon,” MLN 91, 1267-1275). The other examples are: Dante’s Divine Comedy, Rablais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel, Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Goethe’s Faust, Joyce’s Ulysses, and Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. In Mendelson’s account each of these works is unique in its national canon and each is encyclopedic in scope, encompassing the world as it was known at the time. (Mendelson does have a ‘fix’ for the fact the America gets two such books; he links Gravity’s Rainbow to a newly forming international culture.)

Moby Dick is also one of the books Leslie Fiedler discusses in his classic, Love and Death in the American Novel (1966). And it is for that reason that I’m discussing it in this post. Fiedler argues that, while the 18th- and 19th-century European novel is focused on courtship and marriage, the American novel — which is necessarily based on European prototypes — is about “a man on the run, harried into the forest [e.g., Cooper’s Natty Bumpo] and out to sea [e.g., Melville’s Ahab], down the river [e.g., Twain’s Huck Finn] or into combat [e.g., Crane’s Henry Fleming] — anywhere to avoid ‘civilization,’ which is to say, the confrontation of a man and a woman which leads to the fall to sex, marriage, and responsibility” (p. 26).

My object in this post then, is to take a look at the sorts of things one can find in Jockers’ material that bears in some way on Moby Dick in relation to Fiedler’s arguments. I’m not interested in using this material to bolster or weaken Fieldler’s argument; I just want to see how one might bring this kind of material to bear on that kind of argument.

Male Friends

Moby Dick is utterly devoid of women. It is a story about men among men, the sea and, of course, the great white whale. Here’s the opening of Chapter 4, “The Counterpane” (I’m quoting from the Project Gutenberg text):

Upon waking next morning about daylight, I found Queequeg's arm thrown over me in the most loving and affectionate manner. You had almost thought I had been his wife. The counterpane was of patchwork, full of odd little parti-coloured squares and triangles; and this arm of his tattooed all over with an interminable Cretan labyrinth of a figure, no two parts of which were of one precise shade–owing I suppose to his keeping his arm at sea unmethodically in sun and shade, his shirt sleeves irregularly rolled up at various times--this same arm of his, I say, looked for all the world like a strip of that same patchwork quilt. Indeed, partly lying on it as the arm did when I first awoke, I could hardly tell it from the quilt, they so blended their hues together; and it was only by the sense of weight and pressure that I could tell that Queequeg was hugging me.My sensations were strange. Let me try to explain them. When I was a child, I well remember a somewhat similar circumstance that befell me; whether it was a reality or a dream, I never could entirely settle. The circumstance was this. I had been cutting up some caper or other–I think it was trying to crawl up the chimney, as I had seen a little sweep do a few days previous; and my stepmother who, somehow or other, was all the time whipping me, or sending me to bed supperless,–my mother dragged me by the legs out of the chimney and packed me off to bed, though it was only two o'clock in the afternoon of the 21st June, the longest day in the year in our hemisphere. I felt dreadfully. But there was no help for it, so up stairs I went to my little room in the third floor, undressed myself as slowly as possible so as to kill time, and with a bitter sigh got between the sheets.I lay there dismally calculating that sixteen entire hours must elapse before I could hope for a resurrection. Sixteen hours in bed! the small of my back ached to think of it. ... At last I must have fallen into a troubled nightmare of a doze; and slowly waking from it--half steeped in dreams–I opened my eyes, and the before sun-lit room was now wrapped in outer darkness. Instantly I felt a shock running through all my frame; nothing was to be seen, and nothing was to be heard; but a supernatural hand seemed placed in mine. My arm hung over the counterpane, and the nameless, unimaginable, silent form or phantom, to which the hand belonged, seemed closely seated by my bed-side. ... I knew not how this consciousness at last glided away from me; but waking in the morning, I shudderingly remembered it all, and for days and weeks and months afterwards I lost myself in confounding attempts to explain the mystery. Nay, to this very hour, I often puzzle myself with it.Now, take away the awful fear, and my sensations at feeling the supernatural hand in mine were very similar, in their strangeness, to those which I experienced on waking up and seeing Queequeg's pagan arm thrown round me. But at length all the past night's events soberly recurred, one by one, in fixed reality, and then I lay only alive to the comical predicament. For though I tried to move his arm–unlock his bridegroom clasp–yet, sleeping as he was, he still hugged me tightly, as though naught but death should part us twain.

Here is Fiedler’s gloss on that passage (p. 373):

It is worth noting that Ishmael tends to think of himself in the passive, the feminine role; but even more critical is his immediate sense of their relationship as a marriage, which is to say, a permanent commitment: the sort of indissoluble union, which he, as a detached wanderer, has presumably been fleeing. To be sure, it all seems quite comic and unreal, this bedroom scene with a Polynesian sailor -- only a gross parody of marriage; and Ishmael reflects ironically on "the unbecomingness of hugging a male in that matrimonial style…."Yet he begins to grow a little disturbed, too, at the thought of being somewhat trapped. "For though I tried tol…unlock his bridegroom clasp…he still hugged me tightly, as though naught but death should part us twain." The final words echo the marriage service, but in evoking the shadow of death, they also betray an access of panic, arising from an old association between sexual satisfaction and punishment. This suggestion is fortified by the recollection of a childhood nightmare, itself symbolic of rejection, paralysis, castration, and death.

Note, however, that men in the 19th Century were used to sleeping with one another, as Gregory Jusdanis points out in a post at Stanford’s Arcade:

Although most American men of the nineteenth century would not have described this occurrence as a marriage, they would have been used to sleeping with other men. Boys became accustomed to sharing beds with their brothers and then with their roommates in college, and with strangers when traveling. So did soldiers. Physical intimacy between men was economically enforced and privacy not available. And before central heating the male body lying next to you was a literal source of warmth. Men, in short, were familiar with the smell and touch of other men.As we know, in the nineteenth and eighteenth centuries men (as well as women) formed romantic friendships, modes of relationship that allowed much emotional, if not, physical intimacy. The letters and diaries from the Civil War, for instance, reveal men talking to each and about each other with much sweetness and warmth. This was true in earlier decades. The language of affection used by men to write to one another during the American Revolution would put it today in the realm of gay discourse.

Thus what is striking about the passage is not so much the mere fact that two men were sleeping together, but, as Fiedler has pointed out, the marital imagery that Melville used.

Fiedler further remarks (pp. 374-375):

In the childhood episode recalled in Queequeg's arms, the boy Ishmael was not as usual slippered, though he begged for that customary punishment. He was forced, instead, to remain in bed all through the longest day of the year: "sixteen entire hours must elapse before I could hope for a resurrection." He was, in effect, condemned to impotence and death; and to this condemnation his own unconscious subscribed, calling up the phantom hand that held him powerless, awake but involved still in nightmare terror. In his own fantasy, the sentence of a single, endless day had been extended through all eternity: never, never (in either sense) to rise again! And for what crime had he presumably been punished -- "some caper or other," about which he claims not to be sure, but which he thinks may have involved an attempt to climb up his mother's chimney. It is a fantasy more than a fact; and its interpretation suggests itself immediately, casts light on the meaning of chimneys for Melville in such a later story as “I and My Chimney.”Finding himself in a matrimonial deadlock with Queequeg, Ishmael feels again the old threat of impotence and death. But though he is in bed, in that forbidden hugging-place, he is not this time trying to crawl up his mother's chimney. He embraces no woman, no obvious surrogate for the banned mother, only another male, a figure patriarchal enough, in fact, to remind him of George Washington! Surely, the matrimonial hug of such a companion is innocent, only a joke, an accidental result of trying to find a room in an overcrowded town. And though the memory of the nightmare terror of childhood recurs, it recurs purged; for Ishmael has forgiven himself and is free at last to rise: "take away that awful fear, and my sensations…were very similar." Actually, he is free for a reconciliation with the tabooed mother; but this he will not know until the book's end, when, an orphan, he is picked up by "the devious cruising Rachel." His long sentimental re-education has now just begun.

There we have it, Leslie Fiedler on male bonding in Moby Dick. I wouldn’t expect to find anything in Jockers’ charts and word clouds that answers to that in any specific way. But we can find some things in the general vicinity.

American Men on Boats and in the Wilderness

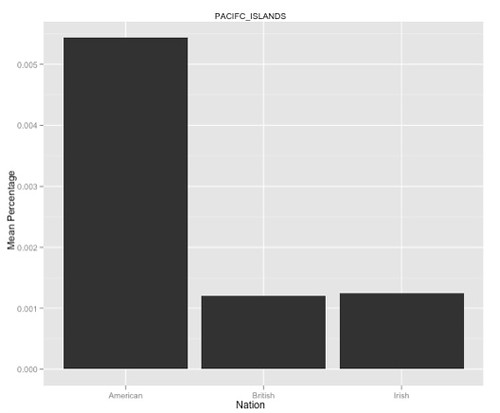

Let’s return to the topic we looked up at there at the beginning of this post, PACIFC ISLANDS AKA SEAS AND WHALING. This chart shows that that topic is much more common among American than British authors:

Here’s a list Jockers sent me showing the 20 books where this is the most prominent topic. They are sorted in descending order. Twelve of them are by Americans, six by Brits, and two by Scots.

| Melville | Herman | Moby-Dick; or, The Whale. | M | American | 1851 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooper | James | The Crater; or, Vulcan's Peak. A Tale of the Pacific | M | American | 1847 |

| Melville | Herman | Mardi and a Voyage Thither | M | American | 1849 |

| Cooper | James | The Sea Lions; or, The Lost Sealers | M | American | 1849 |

| Melville | Herman | Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life | M | American | 1846 |

| Melville | Herman | Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas | M | American | 1847 |

| Ballantyne | Robert | The Coral Island: A Tale of the Pacific Ocean. | M | Scottish | 1858 |

| Stevenson | Robert | Island Nights' Entertainments | M | Scottish | 1893 |

| Poe | Edgar | The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket | M | American | 1838 |

| Williams | William | The journal of Llewellin Penrose, a seaman | M | British | 1815 |

| Hawthorne | Nathaniel | The Village Uncle | M | American | 1842 |

| Farjeon | Benjamin | In a silver sea | M | British | 1886 |

| Duganne | Augustine | The Prince Corsair; or, The Three Brothers of Guzan. A Tale of the Indian Ocean. | M | American | 1850 |

| Russell | William | The Golden Hope : a romance of the deep | M | American | 1887 |

| Hatton | Joseph | A modern Ulysses. : Being the life, loves, adventures, and strange experiences of Horace Durand. | M | British | 1883 |

| Collins | Edward | Miranda : a midsummer madness | M | British | 1873 |

| Payn | James | A prince of the blood; a novel | M | British | 1888 |

| Cooper | James | Mercedes of Castile; or, The Voyage to Cathay | M | American | 1840 |

| Besant | Walter | The captains' room, etc. | M | British | 1883 |

| Clemens | Samuel | Roughing It. | M | American | 1872 |

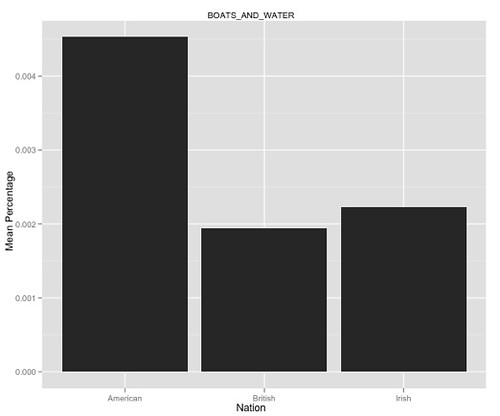

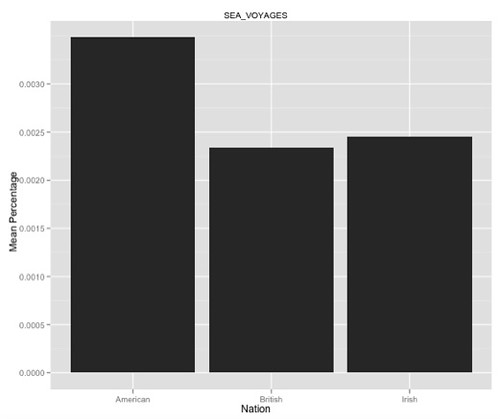

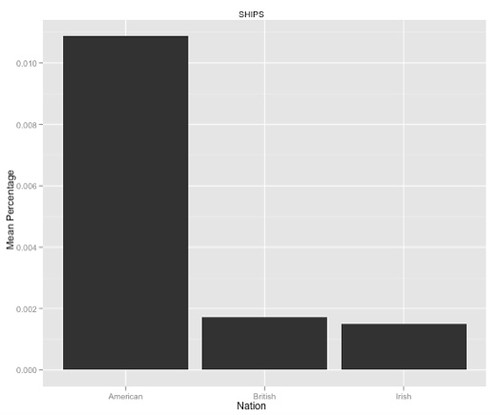

We find a similar national break down for closely related topics. America is the left hand column, Britain the middle, and Ireland the right hand column in all these charts.

BOATS AND WATER

SEA VOYAGES

SHIPS

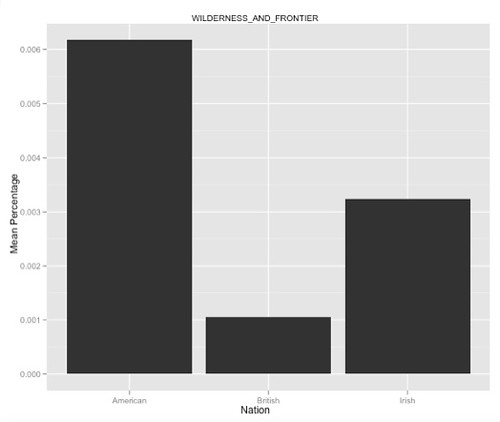

Citing Longfellow’s call for a uniquely national literature, Jockers notes that, in comparison with British, Irish, and Scottish novels, American novels are particularly concerned with the sea, but also the wilderness and the frontier (p. 151). He has also noted (p. 145): Despite the significant role played by ships and seafaring in Ireland, for example the Irish novels are almost completely lacking when it comes to themes associated with the sea.” But then, according to Jockers charts, the same is true for the British texts, and Britain was the dominant naval power of the 19th Century. It used its navy and merchant marine to build and maintain that empire on which the sun never set.

What’s going on? To be sure, the sea was important to America as well; its whaling industry was the largest in the 19th Century and helped make New England rich. But why was the sea more imaginatively salient in America than in Britain, Ireland, or Scotland? Is it because Longfellow called for a national literature? Or is something else going on, something that Leslie Fiedler diagnosed in his best-known book?

Women do not crew ocean-going vessels, at least not in the 19th Century. The sea was a man’s world and, unlike the army, it doesn’t require battle, though of course we could have books about pirating and naval battles. But such batters aren’t required as the underlying raison d'être for sea stories.

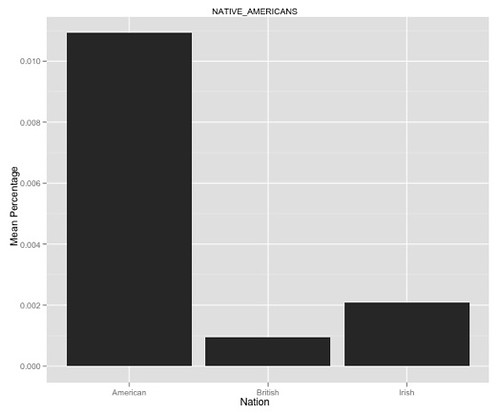

Here are some more “man’s world” topics, as suggested by Fiedler:

WILDERNESS AND FRONTIER

NATIVE AMERICANS

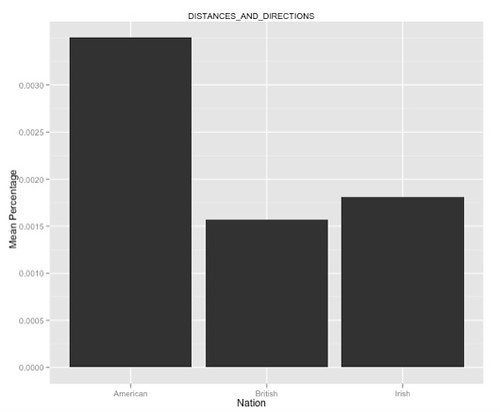

If you’re going to be spending a lot of the time in the wildness running from and hunting down Native Americans, you’re going to talk a lot about DISTANCES AND DIRECTIONS:

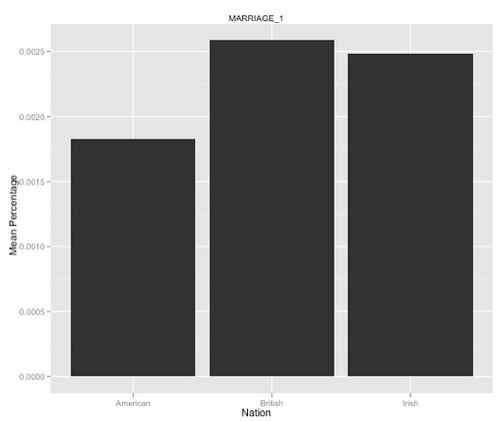

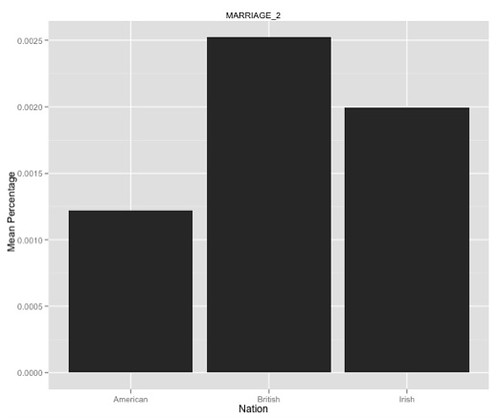

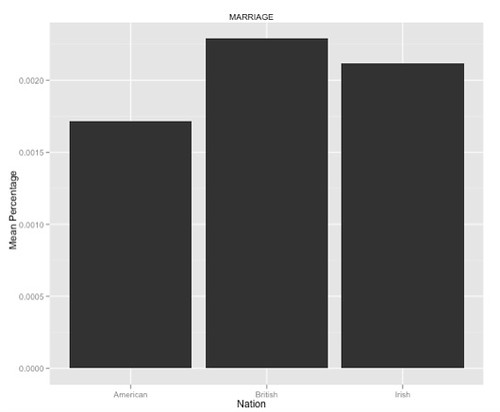

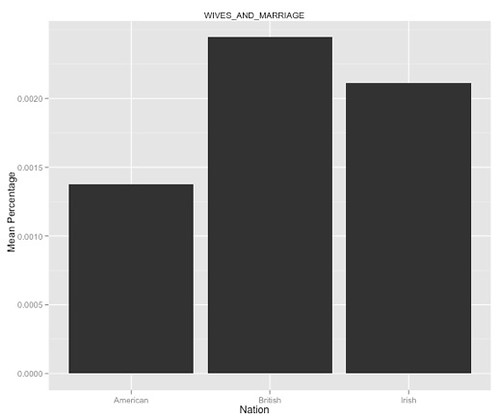

By contrast, the British (middle column), as Fiedler noted, were more concerned about marriage than the Americans:

MARRIAGE 1

MARRIAGE 2

MARRIAGE

WIVES AND MARRIAGE

Why Undertake a Close Reading of Distant Reading?

The wise guy in me, the Tom Sawyer, is tempted to stamp “QED” at this point. But I didn’t undertake this as a demonstration of anything other than the richness of Jockers’ data. I undertook it in the spirit of exploration and discovery. And, to tell the truth, I undertook it to have a bit of intellectual fun.

Still, so what? A traditionalist might be tempted to remark that, if all I’ve done is demonstrate the validity of what Leslie Fiedler had done half a century ago, what’s the point? Why not just read Fiedler? To which I might reply:

But Fiedler was only looking at canonical books.

Aha, replies the traditionalist, if it’s all there in the canon, then why bother with the rest?

There are things I could say in reply, and I’ll say some of them in a minute or two. But the fact is, if the traditionalist insists upon resisting this new-fangled technology, there’s nothing I can say that won’t elicit some triumphant riposte. If I’m clever enough I might force the traditionalist into an ever more incoherent pattern of defense, but I’ll never be able to force him to admit that this new investigative technology is worthwhile. So why bother?

But I will note, first of all, that I’ve only looked at a handful of the themes Jockers has assembled from his corpus of 3,346 19th Century novels. There’s a lot more there. Secondly, with respect to the American canon investigated by Fiedler, Jockers has given us the means to examine it in a much fuller literary context than had been possible before. By examining how literary culture in the large evolved we may begin to understand how the canon emerged.

Let us not forget that, though Moby Dick is now canonical, it was a flop for Melville. Why did it take over 50 years for the book the find an audience? Why wasn’t mid-19th Century literary culture able to countenance it and what happened over the next fifty years that made it acceptable? What role did Moby Dick itself play in that evolution?

* * * * *

Previously:

- Reading Macroanalysis 1: Framing: Hyperobjects, Objectification, and Evolution

- Reading Macroanalysis 2: Metadata and the Emperor’s New Clothes

- Reading Macroanalysis 2.1: How do we make inferences from patterns in collections of books to patterns in populations of readers?

- Reading Macroanalysis 3.0: Style, or the Author Comes Back from the Dead

- Reading Macroanalysis 3.1: Style, or Measuring the Autonomous Aesthetic Realm

- Reading Macroanalysis 4: On the matter of “the”

- Reading Macroanalysis 5: An Interlude on Scale: Micro, Meso, and Macro

- Reading Macroanalysis 6.1: Theme–Dogs, Gold, Slavery, and Awakening

- Reading Macroanalysis 7: Influence, or the evolving dynamic integrity of the aesthetic sphere

No comments:

Post a Comment