Connection: It is a means of linking literary investigation to a wider intellectual world.

Bear with me for a moment, I’ll get there.

Let’s start with the so-called New Criticism and its formalist assertion of textual autonomy. That is, these critics were not particularly interested in analyzing and describing for as such. Rather, they invoked it, and gestured at some of its textual features, as a way of severing the text from context, that is, from readers, writers, society, and history. This resulted in a critical practice in which it is just the critic and the text (in conversation), no literary history, no psychology of any stripe, no sociology, or even philosophy, except what is present in common educated discourse. No special intellectual apparatus is needed to do such criticism. (That, incidentally, made it attractive as a pedagogical approach in the mid-20th century; but let’s set that aside.)

And it is precisely for that reason that no special effort was needed to link academic literary criticism to the wider world, not necessarily the academic world, but the world generally. To the extent that the work was carried out with a commonsense critical armamentarium, anyone could read this criticism – most especially, other critics and academics more generally, and link it to the larger world. There was one problem, however. Critics did not agree on their close readings. Could one text mean different things to different people? Was this an objective intellectual activity, or simply high-flown subjectivity on display?

And so that enterprise was put to the test in the 1960s and 1970s and found wanting, at least by many critics. This gave rise to various forms of contextual criticism. The New Historians employed cultural, social, and political history to insert texts into their historical context and Foucault linked their discourse to broader intellectual currents. Theory, as it came to be called, whether via Derrida, Lacan, Habermas, Kristeva, Deleuze, Spivak, and so forth, was a medium through which literary critics could interact with the larger intellectual world. Evolutionary psychology and (second generation) cognitive science served the same role for various critics who emerged in the mid-1990s. None of these critics, of course, needed formalism as a device to authorize a certain critical approach nor, for whatever reason, were they particularly interested in literary form as an object of description and analysis (Jamison notwithstanding).

And yet, literary works do have very interesting formal features, features well worth describing and analyzing. And there have always been critics who focused on those features via poetics and/or narratology. But this work has been secondary in the American academy. Could it be in part because there seemed to be no way to connect these interests with larger intellectual currents? Perhaps.

That is, various critics may well be fundamentally interested in form. But the imperatives of the existing discipline don’t allow the full flowering of those interests. And so they wither and all but die.

* * * * *

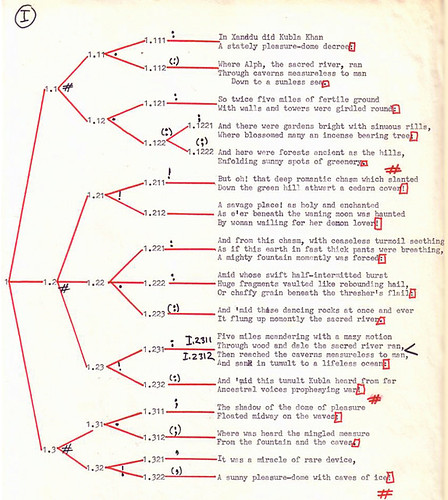

In my own case, its clear that I’ve always found formal analysis interesting. In my sophomore year, I believe it was, I took a cue from Lévi-Strauss and used a feature table in one of my papers. And it was an intuition about form that got me interested in “Kubla Khan” in my senior year. It seemed to me somehow that the two parts of the poem, the first 36 lines and the last 18, had the same structure. It took me a couple of years to figure that out, and when I’d done so, it set the general direction my intellectual career would take.

|

| Some formal features in the first 36 lines of “Kubla Khan” |

I pursued “Kubla Khan” in that way because it interested me. Once I’d found that form, then I recognized the trace, the smell, of computation in it. That’s when I decided to study the cognitive sciences, and that’s why I apprenticed myself to David Hays in graduate school. I wanted to know where that form came from, and how.

When I’m doing practical criticism, describing and analyzing a text, whether written or film, I’m not thinking about computing. That is, I’m not thinking about Turing machines, algorithms, data structures, flow of control, any of that. I’m thinking about patterns in the text. Computation is how I link those patterns to a larger intellectual enterprise. That’s what I was up to in my major methodological and theoretical paper:

Literary Morphology: Nine Propositions in a Naturalist Theory of Form. PsyArt: An Online Journal for the Psychological Study of the Arts. August 2005, Article 060608. http://www.academia.edu/235110/Literary_Morphology_Nine_Propositions_in_a_Naturalist_Theory_of_Form.Here are the nine propositions:

- Literary Mode: Literary experience is mediated by a mode of neural activity in which one’s primary attention is removed form the external world and invested in the text. The properties of literary works are fitted to that mode of activity.

- Extralinguistic Grounding: Literary language is linked to extralinguistic sensory and motor schemas in a way that is essential to literary experience.

- Form: The form of a given work can be said to be a computational structure.

- Sharability: That computational form is the same for all competent readers.

- Character as Computational Unit: Individual characters can be treated as unified computational units in some, but not necessarily all, literary forms.

- Armature Invariance: The relationships between the entities in the armature of a literary work are the same for all readers.

- Elasticity: The meaning of literary works is elastic and can readily accommodate differences in expressive detail and differences among individuals.

- Increasing Formal Sophistication: The long-term course of literary history has been toward forms of increasing sophistication.

- Ranks: Over the long-term literary history has so far evolved forms at four successive cognitive ranks. These are correlated with a richer and more flexible construction of the self.

Propositions 3, 4, 5, and 6 are explicitly stated in terms of computation, and computation is implied in 8 and 9, where computation is the means that allows the formal sophistication that, in turn, eventuates in more or less distinct ranks, with the concomitant structuring of the self.

And now we’re back where we began. What does the idea of computation bring to literary study? Connection: It is a means of linking literary investigation, in particular, the description and analysis of form, to a wider intellectual world.

More later.

No comments:

Post a Comment