Hi Willard,

I know you’re interested in the idea of computer simulations of human mental processes, so I thought you’d be interested in how I got from my vision of such simulation – the Prospero project from the 1976 essay in Computers and the Humanities – to my current hobbyhorse, description. Description, after all, is rather pedestrian and would seem like something of a comedown from the high techno-romance of simulating the mind.

I know you’re interested in the idea of computer simulations of human mental processes, so I thought you’d be interested in how I got from my vision of such simulation – the Prospero project from the 1976 essay in Computers and the Humanities – to my current hobbyhorse, description. Description, after all, is rather pedestrian and would seem like something of a comedown from the high techno-romance of simulating the mind.

It isn’t. In fact, it’s a consequence of that romance, a step along the way. A trail that has proven to be much longer than I’d anticipated back then.

But how could I have known? Sometimes when you venture into the unknown you end up finding something familiar. But you may also end up having your mind altered and your imagination changed.

❖ ❖ ❖

When I went of to SUNY Buffalo back in 1973 I didn’t intend to work on Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129. I was gunning for Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” and did the Shakespeare sonnet as a preliminary exercise. But I never really got around to “Kubla Khan.”

By the time I’d gotten to Buffalo I’d found my way to some of the early work on semantic networks, but didn’t know I’d find someone at Buffalo who could educate me in that art. A fellow graduate student in English, Ralph Reese, had been studying with David Hays (in the Linguistics Department) and he introduced me. It took me a couple of months to become fluent in Hays’s formalism, out of which I wrote a long term paper on some passages from Patterson, Book V.

By that time Hays had become interested in grounding his semantic theory in something, and that something was a feedback model of the mind developed by William Powers, whose book, Behavior: The Control of Perception (1973) had been well-reviewed in Science. So we – Hays and his research group – set out to figure out how to do that, theoretically, though not in simulation. The result was a model where cognition was grounded in perception and action. Though we didn’t use the term, it was a model of embodied cognition.

That’s the model I worked with when I did the Shakespeare sonnet, “The Expense of Spirit.” That is to say, by them time I began working on Shakespeare I’d thought through, in some detail and over the course of two years or so, a model of the mind that when from seeing an apple and eating it through abstract thoughts of charity or even thought itself.

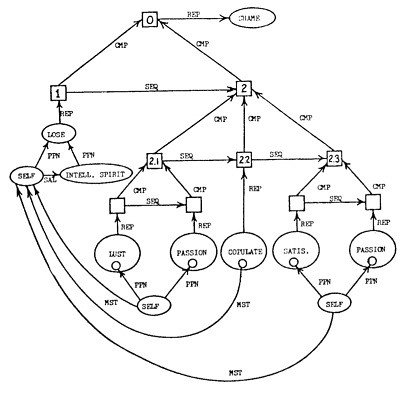

Most of Shakespeare work was in creating the diagrams, such as this one for the concept of shame:

Given the diagrams, 11 of them, writing the prose commentary on them was relatively easy.

But coming up with the diagrams themselves was hard. As I was doing it I was dogged by the problem of meaning – Will this really do the trick? Will it account for the poem’s meaning? When I’d gotten the last diagrams done and had a chance to think about them for a day or so I decided that, yes, that would do. I’ve got an approach to meaning.

❖ ❖ ❖

And that was the last literary text I subjected to the full cognitive treatment. Why, if the work had been successful, as I felt it had been, why stop there?

Several reasons. For one thing, I decided I didn’t know how to do “Kubla Khan”, which had been my objective all along. Sure, I could have hacked something together, but it wouldn’t have been satisfying. This game is played by rules, mostly unspoken ones about form and elegance, but also empirical evidence, and I’d have had to break the rules to do “Kubla Khan.” That was why the work on 129 was so satisfying; I’d gotten there by playing by the rules.

Then there was the realization that most of my work had been with the model, not on the poem. The poem helped determine what kinds of constructions I had to work on, but the actual work was done in terms set by the model and the results were generally applicable beyond the poem. Shame is shame whether it occurs in a Shakespeare sonnet or when you get caught with your sweetie behind the altar. What those diagrams told me about poem – and they really did tell me something – could have been expressed in a somewhat simpler set of diagrams.

So, I continued my work on cognition, in one way, and my work on literature in another. The connection between the two is real, but indirect.

❖ ❖ ❖

In my descriptive work I’ve always got an eye out for something that looks like the trace of computation. The computational work informed and changed my intuitions, and those are what guide me in my work in describing texts these days.

This is most obvious in my work on ring-composition, an obsession I caught from the late Mary Douglas. As you know, ring-form texts are symmetrical about a mid-point, like this: A B C … X … C’ B’ A’. That smells like some kind of nested structure, though I’ve never been able to make that work. But every once in a while I see a glimmer off in the distance, like this post, Ring Form, a Computational Approach.

Meanwhile, simply finding and describing ring-form texts is a satisfying task. The more examples we have to work with, the more clues we’ll accumulate to point our way to the underlying mechanisms. And if someone else ends up identifying the mechanisms, well that’s fine. Research is a cooperative enterprise, no?

And there is this: I now realize, as I didn’t back then, that we’re never going to create that Prospero simulation, or anything like it, until we know more about literature itself. It’s not like the cognitive scientists will figure out the mind, pack it all into a simulation, and then we can have it “read” Hamlet and learn all sorts of cool stuff we never knew before.

No, the cognitivists are not going to get to that point, we’re not going to get to that point until we learn more about literature than we now know. For literary texts and other works of art are one of the few arenas that call upon the full resources of the mind in a “compact” way. I can imagine studying what happens in a person’s mind/brain while they’re reading a novel, watching a movie, or listening to music. But there’s no way we can make detailed observations of a person’s mind/brain during the course of ordinary life, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Our best shot at observing the full mind at work is observing it at play in art – where it is unconstrained by external forces. In art we see the mind exercising its full powers unimpeded. It’s as close as we’ll ever get to “pure” mind.

The key to that treasure starts with description. Description is a necessary step on the way to a deeper understanding of the computational mind.

With regards,

Bill Benzon

With regards,

Bill Benzon

Dear Bill,

ReplyDeleteThis must be the first open letter addressed to me. Often with such things to reply is to ride into battle. But here is, at least for now, no combat. I think in particular of a sentence from your 1976 CHum article with David Hays, "Computational Linguistics and the Humanist": "The key to the... door is semantics, but if that key is to work we must know in advance something of the treasure - some fundamental theoretical problems in les sciences de l'homme - that lies behind the door" (p. 265). With one not-so-small qualification -- that with each knowing-something-of we recreate to some degree what we know -- I think this is exactly right. So an act of description is creative, or more accurately, an act of redesign under constraints which are very difficult to be exact about but which are hard as rocks. Does this make sense?

W

Yes, it does. "Redesign" – yes. After all, we ARE trying to figure out the design. We're attempting to reverse engineer it. And it is exacting, but the constraints are not obvious. I suppose we can invoke Plato's old line about carving Nature at the joints. You can't see where the joints are, but there's a world of difference between a knife stroke that misses the joint and one that goes into it.

ReplyDelete