What Michael Gavin [1] did was to place traditional close-reading and computational criticism in the same intellectual context by using the concept of ambiguity as a tertium quid. My goal in this post is to recount his analysis and, by raising the issue of temporality – poems, and our experiences of them, unfold in time – edge near to some work on I did on a Shakespeare sonnet using “old school” symbolic computation, which I will offer in my next post.

Gavin choose to examine eighteen lines from book 9 of Milton’s Paradise Lost (455-472):

1) Such Pleasure took the Serpent to behold 2) This Flourie Plat, the sweet recess of Eve 3) Thus earlie, thus alone; her Heav’nly forme 4) Angelic, but more soft, and Feminine, 5) Her graceful Innocence, her every Aire 6) Of gesture or lest action overawd 7) His Malice, and with rapine sweet bereav’d 8) His fierceness of the fierce intent it brought: 9) That space the Evil one abstracted stood 10) From his own evil, and for the time remaind 11) Stupidly good, of enmity disarm’d, 12) Of guile, of hate, of envie, of revenge; 13) But the hot Hell that alwayes in him burnes, 14) Though in mid Heav’n, soon ended his delight, 15) And tortures him now more, the more he sees 16) Of pleasure not for him ordain’d: then soon 17) Fierce hate he recollects, and all his thoughts 18) Of mischief, gratulating, thus excites.

I’ve highlighted words that Gavin identified for specific attention, but before commenting on them I want to offer a paraphrase of the passage, a minimal reading as Attridge and Staton [2] call it:

Satan, in the form of the Serpent, comes upon Eve in the garden and is overcome by her beauty. For a moment thoughts of evil are gone and he harbors no ill intent toward her. But as he continues to view her, the knowledge that he cannot have her terminates his pleasure and he hates her (again).

That is to say, the passage follows a movement in Satan’s mind, movement I’ll consider in a bit.

But first, to Gavin. After citing some traditional criticism of this passage, Gavin, without really saying why, zeros in on line nine–though I note that the last bit of criticism he cited was about that line. Note that, as the whole passage is 18 lines long, that line is at the passage’s center. When you drop out the stop-words–that, the, and one–we are left with four terms for investigation, space, Evil, abstracted, and stood. Gavin then produces visualized conceptual spaces for each of those four terms, for the four terms together, and for the entire passage.

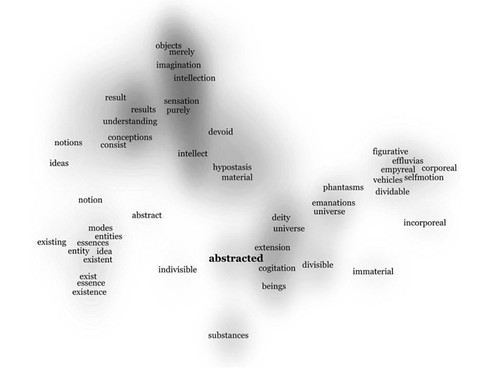

Let’s first consider the space for abstracted:

Gavin notes: “abstracted connects to highly specialized vocabularies for ontology (entity, essence, existence), epistemology (imagination, sensation), and physics (selfmotion)...” (p. 668).

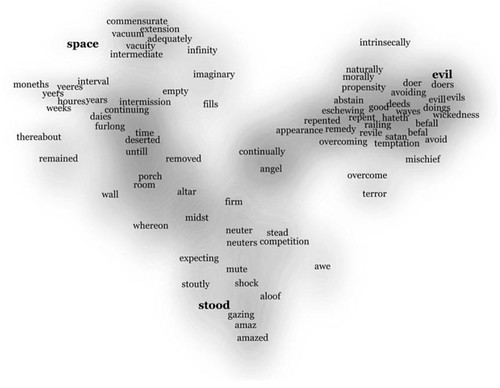

Here’s the space for the four words taken together as a composite vector:

Notice that space, evil, and stood are set in bold type and collocates of each appear in this compound space. But neither abstracted nor any of its collocates appears. As Gavin noted to me in a tweet, “Abstracted is abstracted away. It’s in there in the data, but it’s just too idiosyncratic for its collocates to float to the top.” I note that one edition of Paradise Lost glosses abstracted as withdrawn. That’s apt enough, I suppose, but misses the metaphysical and, well, abstract meanings of the word. Withdrawn could be a mere matter of physical location, but there’s much more than that at stake. As Gavin notes (671-672):

The space of evil is a space of action, of doings and deeds, of eschewing and overcoming, while Satan at this moment occupies a very different kind of space, one characterized by abstract spatiotemporal dimensionality more appropriate to angels, an emptiness visible only as an absence of action and volition.

Notice angel at the center of the diagram.

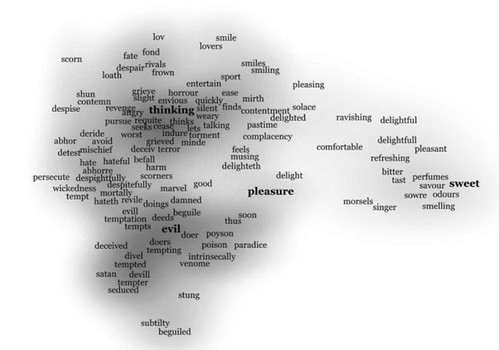

Now consider this visualization based on a composite vector of the entire passage:

Notice that Gavin has emphasized thinking, evil, pleasure, and sweet by setting them in boldface type. See how those first two are placed within the passage itself:

1) Such Pleasure took the Serpent to behold 2) This Flourie Plat, the sweet recess of Eve 3) Thus earlie, thus alone; her Heav’nly forme 4) Angelic, but more soft, and Feminine, 5) Her graceful Innocence, her every Aire 6) Of gesture or lest action overawd 7) His Malice, and with rapine sweet bereav’d 8) His fierceness of the fierce intent it brought: 9) That space the Evil one abstracted stood 10) From his own evil, and for the time remaind 11) Stupidly good, of enmity disarm’d, 12) Of guile, of hate, of envie, of revenge; 13) But the hot Hell that alwayes in him burnes, 14) Though in mid Heav’n, soon ended his delight, 15) And tortures him now more, the more he sees 16) Of pleasure not for him ordain’d: then soon 17) Fierce hate he recollects, and all his thoughts 18) Of mischief, gratulating, thus excites.

The passage begins (line 1) and ends (16) with pleasure while evil appears in the pair of middle lines (9 and 10). Notice, furthermore, that the passage moves through sweet twice on the way from pleasure in line one to evil in line nine while thoughts (rather than thinking) occurs in the second half of the passage in the line after pleasure in line 16. And of course, the mood has changed from the beginning to the end. In the beginning the pleasure seems pure but at the end it is attended by the knowledge that it is unavailable.

I don’t know quite what to make of that. But just what do I mean by “that”? On the one hand Gavin’s analytic method is inherently spatial, revealing a geometry of meaning, albeit a geometry in a high dimensional space. This eighteen line passage is characterized by a subspace in which four terms are prominent: thinking, evil, pleasure, sweet. Those four terms are co-present in that subspace.

In the poem itself, however, those four terms appear in sequence, and in a sequence that has a suspicious order. Two of them form a chiasmus: pleasure...evil, evil... pleasure. A third, sweet, fits nicely into the pattern, so nicely that I’d really like the fourth, thinking, to mirror the position of sweet, yielding:

pleasuresweetsweet

evilevil

thinkingthinkingpleasure

That’s not what we have. What we have, instead, is this:

pleasuresweetsweet

evilevilpleasure

thoughts

That we have a single occurrence of thoughts instead of a double occurrence of thinking isn’t what bothers me, ever so little. The two terms are obviously very closely related in meaning. It’s the order that bothers me. But only a little.

In the first half of the passage, Satan’s pleasure in Eve’s sweet presence abstracts him from his inherent evil. The second half of the passage works to reverse that through thought. Satan notes that further pleasure is not available to him and so thoughts of evil return to him. Somehow I feel that the ordering of these words is necessary to maintaining the coherence of the subspace.

In some way, I suppose, Gavin is getting at the same phenomenon when he says (p. 672):

When taken as a whole, the lines describe a kind of evil thinking, suddenly confronted by an unexpected pleasure of sensation. The words that orbit thinking form rings of association that descend toward evil on one side and connect loosely, impotently toward solace on the other.

We might say that the space Satan briefly occupies is outside history, or that it provides history’s conditions of possibility and is therefore conceivable only by abstracting history away.

But Gavin doesn’t conjure with how the poem is timed. But then, it’s not clear that I can do anything but conjure. Just what is going on, those mechanisms are hidden.

But I will offer one last comment before moving on. This passage seems rather like Shakespeare’s “The expense of spirit”, which Gavin referenced in an early footnote. As you may recall, the first 12 lines offers us a man moving feverishly from desire, through pleasure, and then to disgust, which in turn gives way to desire, pleasure, disgust, and so on and so forth, to no end. There is no escape. And that is what we are told in the concluding couplet:

All this the world well knows; yet none knows wellTo shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

But that couplet is articulated from a space that is a distance from, abstracted from, the feverish hell of the first twelve lines. It is as though Milton has taken the temporal gap that separated lines 1-12 from 13-14 in Shakespeare’s sonnet and transformed it into a spatial gap separate Satan from his evil.

In my next post I’ll take a look at Shakespeare’s sonnet.

References

[1] Michael Gavin, Vector Semantics, William Empson, and the Study of Ambiguity, Critical Inquiry 44 (Summer 2018) 641-673: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/698174

Ungated PDF: http://modelingliteraryhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Gavin-2018-Vector-Semantics.pdf

[2] Derek Attridge and Henry Staten, The Craft of Poetry: Dialogues on Minimal Interpretation, Routledge 2015.

No comments:

Post a Comment