Wednesday, April 30, 2014

Tuesday, April 29, 2014

DH2013 Busa Award Lecture by Willard McCarty

If you're a digital humanist, or curious about the species, listen to this lecture, carefully!

Roughly at 12:12:

The primary historical object I want to bring into focus and call on for help is the Otherness of computing, not its user friendliness, ubiquitous presence of social power...I want to grab on to the fear this Otherness provokes and reach through it to the otherness of the techno-scientific tradition from which computing comes. I want to recognize and identify this fear of Otherness, that is the uncanny, as for example, Sigmund Freud, Stanley Cavell, and Masahiro Mori have identified it, to argue that this Otherness is to be sought out and cultivated, not concealed, avoided, or overcome. That it’s sharp opposition to our somnolence of mind is true friendship.

Somewhat later: "If we’re not changed by computing, we’re imprisoned by it."

Monday, April 28, 2014

I’m Lost in the Web & Digital Humanities is Sprouting All Over

When this is posted it will be the 2398th post on New Savanna since my first post on April 4, 2010 (which now contains nothing but a busted link). Some of those are just links to other material, many of them my photos, while a few others are long-form posts one a variety of subjects: literature, animation, cognitive psychology, society, cultural evolution, graffiti, and a few others. The thing is, despite the fact that I did those posts, I no longer know what I’ve done.

When I look through old posts for something the merits reposting (thus saving me the time of writing something new) I find posts I’d forgotten about. And when I go looking for something I know I’ve written, it sometimes takes me awhile to find it. Sometimes I find it by search through my tags. Sometimes I’ll search on a word or phrase I figure is likely to be in the target post, but not in many others. This searching may take several minutes or more.

I suppose that’s not bad. But, really, I’d like to find stuff instantly. Just like I recall something from my own mind.

But whoops! my own mind doesn’t work like that either. Sometimes I can remember things, sometimes I can’t.

What’s interesting though is that blogging has shifted the boundary between my private notes and public thoughts.

Sunday, April 27, 2014

Saturday, April 26, 2014

What is computing? It's more than doing sums!

Look at some of the presentations for the 2nd Workshop on Mind, Mechanism, and Mathematics (Mat 12-13, NYC):

- Mark Braverman (Princeton University) - Protecting a Conversation Against Adversarial Interference

- Rebecca Schulman (Johns Hopkins University) - Software for Matter: Programming the Morphogenesis, Replication and Metamorphosis of Everyday Things

- Martin Davis (New York University and UC Berkeley) - Gödel, Mechanism, and Consciousness

- Benjamin Koo (Tsinghua University) - CELL: A Cognitive Extreme Learning Lab

- Paul Grant (University of Cambridge) - Synthetic Spatial Patterning Using Two-Channel Quorum-Sensing Signaling

Check out the Big Questions:

1. The Mathematics of Emergence: The Mysteries of Morphogenesis2. Possibility of Building a Brain: Intelligent Machines, Practice and Theory3. Nature of Information: Complexity, Randomness, Hiddenness of Information4. How should we compute? New Models of Logic and Computation

Friday, April 25, 2014

Krugman and Brooks on Piketty

No, what’s really new about “Capital” is the way it demolishes that most cherished of conservative myths, the insistence that we’re living in a meritocracy in which great wealth is earned and deserved.

For the past couple of decades, the conservative response to attempts to make soaring incomes at the top into a political issue has involved two lines of defense: first, denial that the rich are actually doing as well and the rest as badly as they are, but when denial fails, claims that those soaring incomes at the top are a justified reward for services rendered. Don’t call them the 1 percent, or the wealthy; call them “job creators.”

But how do you make that defense if the rich derive much of their income not from the work they do but from the assets they own? And what if great wealth comes increasingly not from enterprise but from inheritance?

Piketty wouldn’t raise taxes on income, which thriving professionals have a lot of; he would tax investment capital, which they don’t have enough of ... Politically, the global wealth tax is utopian, as even Piketty understands. If the left takes it up, they are marching onto a bridge to nowhere. But, in the current mania, it is being embraced.

This is a moment when progressives have found their worldview and their agenda. This move opens up a huge opportunity for the rest of us in the center and on the right. First, acknowledge that the concentration of wealth is a concern with a beefed up inheritance tax.

Second, emphasize a contrasting agenda that will reward growth, saving and investment, not punish these things, the way Piketty would. Support progressive consumption taxes not a tax on capital. Third, emphasize that the historically proven way to reduce inequality is lifting people from the bottom with human capital reform, not pushing down the top.

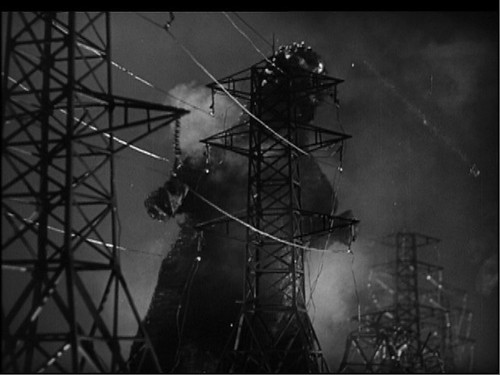

Godzilla and Wuthering Heights, Kissing Cousins?

In what way is Godzilla, King of the Monsters, like Wuthering Heights? You might think that they are so different that their resemblances are of little account. Sure, they’re both about people in conflict, but other than that... After all, one is a classic text of English literature written in the early 19th Century. The other is an Americanized version of a mid-20th Century Japanese creature feature that has spawned almost 30 sequels, all about monsters.

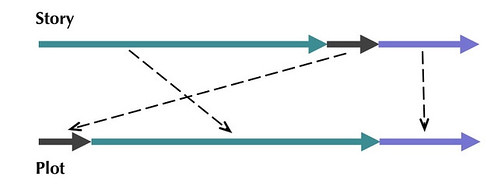

Yes, they ARE very different texts. But they are alike in a very profound way: form. Consider the following diagram, which applies to both texts:

The upper line divides indicates story in temporal order, from first (on the left) to last (on the right). The line shows these events divided into three segments. The lower line depicts how those three sets of events are re-ordered in the text.

Thus both stories have a certain sequence of events that happens relatively late in the overall sequence. As the stories are actually narrated, however, this late sequence is moved to the beginning and the other sequences are adjusted to accommodate. In both cases the sequence that is moved involves a narrator external to the main sequence but known to the characters in it.

Godzilla, King of the Monsters (1956) is an Americanized version of the original Japanese Gojira (1954). Large chunks of the Japanese original were removed and new footage shot involving an American reporter, Steve Martin. Martin is in Tokyo on his way to report a story in Cairo. While there he decides to visit some friends and Godzilla appears. He reports on the story as it develops and is injured when Godzilla finally attacks Tokyo.

The film opens with shots of a wrecked Tokyo. We see Martin in the wreckage of some building; then he’s on a stretcher; and he’s finally placed the on the floor of a hospital. He sees one of his friends and they talk. She leaves to get a doctor and he begins recalling the story from the beginning.

In Wuthering Heights the outsider is a man named Lockwood. He’s come to rent a house, Thrushcross Grange, for the summer and meets the principal characters in another house, Wuthering Heights. He then hears a story about two generations of love and loss from one of those characters, Nellie Dean. But, like Steve Martin, he plays no causal role in the events he’s narrating.

In the abstract, one could imagine that the filmmakers who Americanized the Japanese film, Gojira, were influenced by Brontë’s text. But that seems implausible to me. The more plausible explanation is that they faced a similar problem and so arrived at a similar solution. We know the problem the American producers faced; they had to present a Japanese story to an American audience, and when the two countries had recently been at war. It’s not obvious to me just what problem Brontë faced. Did she regard her core story as being so strange that she had to create Lockwood to hear it from Nellie Dean and then tell it to her audience? If so, why?

These two stories are alike in another respect: one of the principle characters in each is an outsider to the world where the story is set. In Wuthering Heights it is Heathcliff who is the outsider. His background is obscure. We know only that he came from the city. He’s depicted as wild and impetuous, almost feral. In Godzilla, King of the Monsters, it is Godzilla who is the outsider. This resemblance suggests something about why the story has to be told through an outsider, something requiring further thought.

* * * * *

Given my interest in form, this case is intrinsically interesting to me. I want to know how this form works.

But I’m also interested in the fact that this resemblance is a superficial one, superficial in then sense that it is readily apparent. You don’t have to undertake an extensive and possibly problematic analysis to discover this similarity between these two texts. The resemblance is available to simple and straightforward descriptive means.

But it was largely fortuitous that I happened to notice this resemblance. If recent posting had brought not Wuthering Heights to mind at a time when I’d just finished working on Gojira, I might not have noticed this resemblance. The academic study of culture is organized in such a way – along nationalist lines, Popular culture vs. high culture – that few researchers are unlikely to be interested in such very different texts.

Not only do we need to place more emphasis on description, to ride a favorite hobbyhorse, but we need to undertake extensive comparative work encompassing all texts regardless of their origins.

Thursday, April 24, 2014

Is conflict necessary to plot?

From still eating oranges:

The necessity of conflict is preached as a kind of dogma by contemporary writers’ workshops and Internet “guides” to writing. A plot without conflict is considered dull; some even go so far as to call it impossible. This has influenced not only fiction, but writing in general—arguably even philosophy. Yet, is there any truth to this belief? Does plot necessarily hinge on conflict? No. Such claims are a product of the West’s insularity. For countless centuries, Chinese and Japanese writers have used a plot structure that does not have conflict “built in”, so to speak. Rather, it relies on exposition and contrast to generate interest. This structure is known as kishōtenketsu.Kishōtenketsu contains four acts: introduction, development, twist and reconciliation. The basics of the story—characters, setting, etc.—are established in the first act and developed in the second. No major changes occur until the third act, in which a new, often surprising element is introduced. The third act is the core of the plot, and it may be thought of as a kind of structural non sequitur. The fourth act draws a conclusion from the contrast between the first two “straight” acts and the disconnected third, thereby reconciling them into a coherent whole. Kishōtenketsu is probably best known to Westerners as the structure of Japanese yonkoma (four-panel) manga; and, with this in mind, our artist has kindly provided a simple comic to illustrate the concept.

See Azumanga Daioh.

Toward a Computational Historicism. Part 4: Into the Autonomous Aesthetic

This is the fourth and last in a series of posts that began with Discourse and Conceptual Topology, moved to From History to Abstraction, and then Abstraction at the Time Scale of History.

In the 6th pamphlet from Stanford’s Literary Lab, “Operationalizing”: or, the Function of Measurement in Modern Literary Theory, Franco Moretti ended with a call to explicate the theoretical consequences of computing for literary study. That’s what I’ve been doing. It is now time to wrap up the exposition.

Let us begin with a passage from one of the last essays published by Edward Said, Globalizing Literary Study (PMLA, Vol. 116, No. 1, 2001, pp. 64-68). In his second paragraph Said notes: “An increasing number of us, I think, feel that there is something basically unworkable or at least drastically changed about the traditional frameworks in which we study literature“ (p. 64). Agreed. He goes on (pp. 64-65):

I myself have no doubt, for instance, that an autonomous aesthetic realm exists, yet how it exists in relation to history, politics, social structures, and the like, is really difficult to specify. Questions and doubts about all these other relations have eroded the formerly perdurable national and aesthetic frameworks, limits, and boundaries almost completely. The notion neither of author, nor of work, nor of nation is as dependable as it once was, and for that matter the role of imagination, which used to be a central one, along with that of identity has undergone a Copernican transformation in the common understanding of it.

What has happened to all those things, as Alan Liu has noted in “The Meaning of the Digital Humanities” (PMLA 128, 2013, 409-423) is that they have dissolved into vast networks of objects and processes interacting across many different spatial and temporal scales, from the syllables of a haiku dropping into a neural net through the process of rendering ancient texts into movies made in Hollywood, Bollywood, or “Chinawood” (that is, Hengdian, in Zhejiang Province) and shown around the world.

If it is difficult to gain conceptual purchase on the autonomous aesthetic realm, then perhaps we need new conceptual tools. Computation provides tools that allow us to examine large bodies of texts in new ways, ways we are only beginning to utilize. But computation also gives us new ways of thinking about the mind, and that is particularly important, and problematic, in this context.

Wednesday, April 23, 2014

Toward a Computational Historicism. Part 3: Abstraction at the Time Scale of History

Poets are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration; the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which humanity casts upon the present; the words which express what they understand not; the trumpets which sign to battle, and feel not what they inspire; the influence which is moved not but moves. Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.

–Percy Bysshe Shelley

In the first post in this series, Discourse and Conceptual Topology, I reviewed network models on three scales, micro, meso, and macro. In the second post, From History to Abstraction, I moved to the micro scale and argued that the mechanism of abstraction proposed by David Hays gives us a way of thinking about how a historical process can lead to subsequent abstraction and illustrated the model through an examination of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129. In this post I examine Heuser and Le-Khac on the 19th Century British novel and undertake a formal comparison of The Winter’s Tale and Wuthering Heights in which I argue that Brontë had the advantage of conceptual machinery unavailable to Shakespeare, though in some way anticipated by him. I hope to conclude this series with a fourth post in which I return to purely theoretical and methodological matters.

History: Showing and Telling

As we all know, one of the major problems of literary studies up to now is that it has concentrated its attentions on a relatively small body of texts, the so-called canon, and has allowed the examination of those texts to stand as a proxy for all of literary history. The assumption is either that, because of their quality, those are the only texts that matter or, perhaps, their quality allows them to “stand-in” for the rest. The widespread availability of powerful computers now allows as to put these assumptions to the test or, rather, simply to abandon them.

Sister disciplines have developed techniques for analyzing large bodies of texts, corpus linguistics, and literary critics are applying these to newly available digital text collections. I want to examine one such study, Ryan Heuser and Long Le-Khac, A Quantitative Literary History of 2,958 Nineteenth-Century British Novels: The Semantic Cohort Method (Stanford Literary Lab, Pamphlet 4, May 2012; HERE is an older post that looks at this study). Their corpus included almost 3000 British novels spanning the period from 1785 to 1900. What they discovered, roughly speaking, is a shift from abstract terms to concrete, which they characterize as shift from telling (abstract terminology) showing (concrete terms). They read this shift through Raymond Williams (The Country and the City) as reflecting a population shift from small rural closely-knit communities to large urban communities where people are constantly amid strangers.

Here is how Heuser and Le-Khac characterize the texts toward the beginning of the period (p. 35):

Thinking in terms of the abstract values, the tight social spaces in the novels at the left of the spectrum are communities where values of conduct and social norms are central. Values like those encompassed by the abstract values fields organize the social structure, influence social position, and set the standards by which individuals are known and their behavior judged. Small, constrained social spaces can be thought of as what Raymond Williams calls “knowable communities,” a model of social organization typified in representations of country and village life, which offer readers “people and their relationships in essentially knowable and communicable ways” (Country 165). The knowable community is a sphere of face-to-face contacts “within which we can find and value the real substance of personal relationships” (Country 165). What’s important in this social space is the legibility of people, their relationships, and their positions within the community.

Toward the end of the period writers wrote and readers read texts Ryan and Le-Khac characterize like this (p. 36):

If this is how the abstract values fields are linked to a specific kind of social space, then we can make sense of their decline over the century and across the spectrum. The observed movement to wider, less constrained social spaces means opening out to more variability of values and norms. A wider social space, a rapidly growing city for instance, encompass- es more competing systems of value. This, combined with the sheer density of people, contributes to the feeling of the city’s unordered diversity and randomness. This multiplicity creates a messier, more ambiguous, and more complex landscape of social values, in effect, a less knowable community... The sense of a shared set of values and standards giving cohesion and legibility to this collective dissipates. So we can understand the decline of the abstract values fields—these clear systems of social values organized into neat polarizations—as a reflection of their inadequacy and obsolescence in the face of the radically new kind of society that novels were attempting to represent.

The upshot (p. 36): “Alienation, disconnection, dissolution—all are common reactions to the new experience of the city.”

I have no problems with this, as far as it goes. But, in light of Hays mechanism of abstraction, where abstract terms are defined over terms, I want to suggest that something else might be going on. Perhaps all those concrete terms in the later novels are components of abstract patterns, patterns defining terms which may not even be named in the text (or elsewhere).

That is to say, abstract terms do not contain their definitional base somehow wrapped up “inside” them. The signified is not enclosed within the signifier. It lies elsewhere. When constructing discourse intended to circulate within a known world one can rely on others to possess, internally, the defining pattern of terms. But when sending a text to circulate among strangers, a message in a bottle, one cannot rely on them to already to have internalized the definitional patterns. One must also supply the patterns themselves. And once the patterns are there, perhaps the terms they define become irrelevant. Perhaps, in fact, this situation is an opportunity to gather new patterns – which others may or may not name and rationalize.

The fact that these later novels do not use abstract terms so liberally thus does not necessarily mean that those texts do not imply abstraction. Perhaps they are but using abstraction in a different mode; they are supplying the patterns themselves.

Let us consider a text from the end of that period, Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness. If alienation, disconnection, and dissolution are your cup of tea, that text abounds in them, though it’s not a novel of the city at all. To be sure, it starts with four men on a yacht in the Themes River, but those men are not really of London in that moment, though they may be in it. Though the story moves to the European continent, and ends there too, its heart is in Africa, but colonial Africa.

I don’t have the means to examine the lexical usage in the whole text, so I don’t know where Conrad’s text appears on the continuum between showing and telling. But the text is a highly abstracted and elliptical. A key rhetorical indicator: only two of the characters are known by name, Kurtz and Marlow; the rest are known by title, the Director, the Intended. People are merely nodes in a social net, one stretched to the breaking point.

But I want to focus on one paragraph; at about 1500 words it’s the longest one in the text. Prior to this point Marlow has made it clear that his African crew was just barely competent, his helmsman in particular. It this point in the trip the boat is attacked from the shore and the helmsman is speared. Bleeding profusely, he falls to the deck. At this point Marlow interrupts the story and delivers a long set of comments about Kurtz – the paragraph of interest – and then, when he’s done, he returns to the helmsman bleeding on the deck and throws him overboard. This paragraph is strongly and dramatically marked.

The paragraph starts with the Intended and moves from there to Kurtz and his bald head and then to the all-important ivory, the “fossil” as it is called. Then there’s talk of the moral comforts and pressure of home, which are gone in the jungle, Kurtz’s pan-European background – “His mother was half-English, his father was half-French. All Europe contributed to the making of Kurtz...” – his education, his ideas, his beautifully-written report to the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs, the unspeakable practices Kurtz allowed himself, and, of course, the report’s postscript: “Exterminate all the brutes!” The paragraph ends with something of an abbreviated eulogy for his helmsman:

I missed my late helmsman awfully,—I missed him even while his body was still lying in the pilot-house. Perhaps you will think it passing strange this regret for a savage who was no more account than a grain of sand in a black Sahara. Well, don't you see, he had done something, he had steered; for months I had him at my back—a help—an instrument. It was a kind of partnership. He steered for me—I had to look after him, I worried about his deficiencies, and thus a subtle bond had been created, of which I only became aware when it was suddenly broken. And the intimate profundity of that look he gave me when he received his hurt remains to this day in my memory—like a claim of distant kinship affirmed in a supreme moment.

Immediately before those lines Marlow weighs Kurtz against this helmsman: “No; I can't forget him, though I am not prepared to affirm the fellow was exactly worth the life we lost in getting to him.” He thus implies that the dead helmsman was more to him than Kurtz. The fellowship of one African is worth more than the accomplishments of a remarkable Englishman.

Marlow is not only measuring one man against another in that sentence, he’s measuring African against Europe, which is rather a more abstract comparison. In that moment Africa noses out Europe in the comparison, a rather extraordinary thing, no? To be sure, the terms of comparison are rigged, as Chinua Achebe pointed out in a lecture entitled “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.” Still, it is an extraordinary moment.

But was it prophetic in Shelley’s sense? With the advantage of hindsight one might claim it was, for not long thereafter Europe was singing and dancing to the music of the African diaspora and sun tans came in vogue, perhaps in imitation of African skin, as Ann Douglas argues in Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920's (Farrar, Straus, 1995).

But the point I really want to make is more modest. And I want to make it by way of Leslie Fiedler. Early in Love and Death and the American Novel (1966, pp. 32-33) he says:

The series of events which includes the American and French Revolutions, the invention of the novel, the rise of modern psychology, and the triumph of the lyric in poetry, adds up to a psychic revolution . . . a new kind of self, a new level of mind; for what has been happening since the eighteenth century seems more like the development of a new organ than a mere finding of a new way to describe old experience.

Is Fiedler correct about this? But I do not see how one can account for this “new organ” by reference to our biological nature – Fieldler is talking metaphorically – for this new organ arose long after our biological nature had stabilized. Its origin thus must be found in the culturally evolved refashioning of biological materials.

This new organ is more is constructed in the mind and not the body or, if you will, it is in the brain, but not thereby of the body. It is the sort of thing that culture can craft and I suggest that Piaget’s notion of reflective abstraction and Hay’s concept of abstract definition tell us something of the machinery culture has at its disposal. The kind of evidence Hauser and Le-Khac offer about the British novel is consistent with this view, though it would require more work to offer a stronger statement on the matter.

[I’ve examined the Conrad paragraph in some detail. I situate this paragraph in Conrad’s text in this post: The Heart of Heart of Darkness. I undertake an informal analysis of that paragraph, almost at the sentence level, in Heart of Darkness 6: Some Informal Notes about the Nexus. I examine Marlow’s comparison of the helmsman and Kurtz in Marlow’s Calculation. All of these posts are included in Heart of Darkness: Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis on Several Scales (PDF).]

From Shakespeare to Bronte

Now let’s take a look at Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale and Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. Both narratives span two generations in which the first generation narrative ends in tragedy while the second-generation narrative ends happily. To be sure, the happy ending of Wuthering Heights is muted and rather bizarre in that Heathcliff must reunite with his beloved Catherine in the grave whereas Leontes’ beloved Hermione turns out to be alive at the end. But Heathcliff goes happily to that grave.

The first thing that interests me is that Brontë’s novel uses a complex double narration—Nellie Dean to Lockwood, Lockwood to the reader—of a sort that is completely absent in Shakespeare (and his contemporaries). I’m suggesting that she has conceptual machinery that he didn’t have and that double narration is the most obvious trace of that machinery. This machinery allows how to manipulate and reorder the events of her story in a way that Shakespeare could not.

Brontë opens her narrative with events that in fact happen late in the two-generation history she is telling. Catherine Linton née Earnshaw has been long dead and her daughter is coming into her majority. Heathcliff has taken over both estates, Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange, while residing at Wuthering Heights. Lockwood has just come off a failed summer romance and has decided to rent Thrushcross Grange.

As the novel opens Lockwood is narrating the story of his visit to Heathcliff at the Heights, two visits actually. Those visits extend through three chapters (of 34). It isn’t until the fourth chapter that we meet Nelly Dean and get a clear indication that this is not going to be the story of Lockwood getting over his failed summer romance, but rather a story about the Earnshaws, Lintons, and Heathcliff.

While there is much to remark on in these opening chapters, I want specifically to look at the second. What happens is that Lockwood makes a series of mistaken inferences about the relationships among the people residing at the Heights. There are five, Heathcliff, Catherine Linton, Hareton Earnshaw, and two servants, Joseph and Zillah. First he presumes that Catherine was Heathcliff’s wife:

'It is strange,' I began, in the interval of swallowing one cup of tea and receiving another--'it is strange how custom can mould our tastes and ideas: many could not imagine the existence of happiness in a life of such complete exile from the world as you spend, Mr. Heathcliff; yet, I'll venture to say, that, surrounded by your family, and with your amiable lady as the presiding genius over your home and heart--''My amiable lady!' he interrupted, with an almost diabolical sneer on his face. 'Where is she--my amiable lady?''Mrs. Heathcliff, your wife, I mean.''Well, yes--oh, you would intimate that her spirit has taken the post of ministering angel, and guards the fortunes of Wuthering Heights, even when her body is gone. Is that it?'Perceiving myself in a blunder, I attempted to correct it. I might have seen there was too great a disparity between the ages of the parties to make it likely that they were man and wife. One was about forty: a period of mental vigour at which men seldom cherish the delusion of being married for love by girls: that dream is reserved for the solace of our declining years. The other did not look seventeen.Then it flashed on me--'The clown at my elbow, who is drinking his tea out of a basin and eating his broad with unwashed hands, may be her husband: Heathcliff junior, of course. Here is the consequence of being buried alive: she has thrown herself away upon that boor from sheer ignorance that better individuals existed! A sad pity--I must beware how I cause her to regret her choice.' The last reflection may seem conceited; it was not. My neighbour struck me as bordering on repulsive; I knew, through experience, that I was tolerably attractive.'Mrs. Heathcliff is my daughter-in-law,' said Heathcliff, corroborating my surmise. He turned, as he spoke, a peculiar look in her direction: a look of hatred; unless he has a most perverse set of facial muscles that will not, like those of other people, interpret the language of his soul.

Notice that, upon correction, Lockwood infers that Hareton is married to Catherine and is Heathcliff’s son. He is mistaken on both counts. Heathcliff is without issue (his son had died shortly before Lockwood arrived) and Catherine and Hareton are not married, though they will have become engaged by the end of the novel, after we’re been told some 30 chapters worth of events.

Lockwood’s mistaken inferences were natural enough given the existing customs about who lives together under one roof, customs which aren’t so different from current one, though servants are not so prevalent now as they were in the 19th Century. The effect is to turn the story into something of a mystery, it seems to me, is to foreground the fact of family-hood. Just how is it that these came to be living together under one roof?

Not only do these two texts span two generations, both are explicitly concerned about character as well. In The Winter’s Tale this takes the form of commentary about how a lowly shepherdess, Perdita, is nonetheless worthy of a prince, Florizel. In Wuthering Heights it takes the form of remarks about how the personalities of second-generation people are blends of the personality traits exhibited by their first generation parents. Such discussion, I submit, was just beyond Shakespeare and his audience, but was routine for Brontë and hers.

Let us first examine a passage from The Winter’s Tale. Polixenes arrives at the Shepard’s hut and Perdita sees him for the first time, Act IV Scene IV:

Polixenes

Shepherdess,

A fair one are you--well you fit our ages

With flowers of winter.

Perdita

Sir, the year growing ancient,

Not yet on summer's death, nor on the birth

Of trembling winter, the fairest

flowers o' the season

Are our carnations and streak'd gillyvors,

Which some call nature's bastards: of that kind

Our rustic garden's barren; and I care not

To get slips of them.

Polixenes

Wherefore, gentle maiden,

Do you neglect them?

Perdita

For I have heard it said

There is an art which in their piedness shares

With great creating nature.

Polixenes

Say there be;

Yet nature is made better by no mean

But nature makes that mean: so, over that art

Which you say adds to nature, is an art

That nature makes. You see, sweet maid, we marry

A gentler scion to the wildest stock,

And make conceive a bark of baser kind

By bud of nobler race: this is an art

Which does mend nature, change it rather, but

The art itself is nature.

Though Perdita and Polixenes are talking of the breeding of flowers, we in the audience can’t help but read this conversation against the characters in the play. Perdita appears to be base born but in fact she is not. And that seems to be the burden of Shakespeare’s concern: appearances do not tell all.

Turning to Wuthering Heights, we see that Brontë is much more direct and explicit in her examination of character through descent. She takes great pains, almost geometric in their precision, to show how the personalities of second generation characters are derived from the personalities of their parents. It’s not only that this derivation is obvious to readers, but it is obvious to characters in the story, who comment upon it, e.g. Nelly Dean and Joseph. Note the passages Joseph Carroll quotes as he describes these relations of character descent (The Cuckoo's History: Human Nature in Wuthering Heights, Philosophy and Literature 2008, 32: 241-257:

Heathcliff and Catherine are physically strong and robust, active, aggressive, domineering. Edgar Linton is physically weak, pallid and languid, tender but emotionally dependent and lacking in personal force.... Isabella Linton, in contrast, is vigorous and active. She defends herself physically against Heathcliff, and when she escapes from him she runs four miles over rough ground through deep snow to make her way to the Grange. Her son Linton, weak in both body and character, represents an extreme version of the debility that afflicts his uncle Edgar. …. Isabella’s son has “large, languid eyes—his mother’s eyes, save that, unless a morbid touchiness kindled them a moment, they had not a vestige of her sparkling spirit.” Despite his inanition, Linton Heathcliff can be kindled to an impotent rage that recalls his father’s viciousness of temper. Witnessing an episode of the boy’s “frantic, powerless fury,” the old servant Joseph cries in malicious glee, “Thear, that’s t’ father! ... That’s father! We’ve allas summut uh orther side in us.”. … The younger Cathy is as physically robust and active as her mother and her aunt Isabella. She also has her mother’s dark eyes and her vivacity, but she has her father’s blond hair, delicate features, and tenderness of feeling. … Her cousin Hareton Earnshaw is athletically built, has fine, handsome features, and his mind, though untutored, is strong and clear. He has evidently not inherited the fatal addictive weakness in his father’s character. (pp. 247-248)

There is nothing like this in Shakespeare. Thus, while he may be unmatched in his capacity to create rich and subtle characters, for all the talk of nature, breeding, and descent in the fourth act of The Winter’s Tale, he did not use his powers to show this kind of process. In this matter Emily Brontë has—if I may be so heretical—done the master one better. She is depicting an aspect of human life that eluded him.

I leave it as an exercise to the reader to consider whether or not Brontë has factored this descent of personality into components of nature and nurture (breeding) and, if so, what techniques she uses to do so. Were I to undertake this exercise I would probably begin by noting Brontë’s depiction of dogs, some of which are large and violent (e.g. Wolf and Skulker) while others seem quite tamed (the small dog the Linton children fought about in Chapter VI). That is, some dogs seem more or less wild while others are more highly bred for human companionship. Nurture vs. nature exists in both the human and the animal world.

Thus, while the two-generation story at the core of Wuthering Heights bears a strong resemblance to the stories in Pandosto and The Winter’s Tale, the narrative displays two signal characteristics that are absent in those earlier narratives: a complex double narration and a depiction of the descent of character. The two-generation story exists independently of the narrative frame and can be told without it, as I did above. The narrative frame thus exists in addition to the story itself; its narrative machinery is meta to the basic machinery of the story itself.

My argument, then, is that Brontë had the use of conceptual machinery unavailable to Shakespeare, machinery that emerged from the interactions of many readers and writers over the intervening years. Among other things she had the formal strategies embodied in the modern novel itself. Those strategies imply and stand upon the existence of earlier modes, but they also move beyond them. They allow novelists to present and thereby identify new patterns of human experience.

Tuesday, April 22, 2014

The Philological mysteries

I have long known that my discipline is descended from philology, but I've never had a very firm sense of just what philology is other than the study of language with a historical emphasis. Language Log has taken up the quest. Mark Liberman, for whom philology means "an old term for linguistic analysis, and especially comparative and historical linguistics as applied to analyzing and understanding texts in dead languages such as Old English and Middle English", starts off with a post wondering just what Paul de Man meant by philology when he urged a return to philology in one of his late essays. Liberman cites a number of dictionary definitions of the term and his commenters have quite a bit to say on the matter.

He adds another post, based on remarks by one of his commenters, Omri Ceren, and himself notes "the supreme intellectual prestige of 'philology' in Europe through the middle of the 19th century, and to some extent until WW I." He closes with a publisher's blurb for James Turner, Philology: The Forgotten Origins of the Modern Humanities (2014):

Many today do not recognize the word, but "philology" was for centuries nearly synonymous with humanistic intellectual life, encompassing not only the study of Greek and Roman literature and the Bible but also all other studies of language and literature, as well as religion, history, culture, art, archaeology, and more. In short, philology was the queen of the human sciences. How did it become little more than an archaic word? In Philology, the first history of Western humanistic learning as a connected whole ever published in English, James Turner tells the fascinating, forgotten story of how the study of languages and texts led to the modern humanities and the modern university.

The redoubtable Victor Mair weighs in with on Philology and Sinology, explaining that:

a Sinologist is a philologist who specializes on matters pertaining to China. To which [people] will generally ask, "Huh, what's that?" Whereupon I will say, "A philologist is someone who studies ancient texts for the purpose of understanding the languages and cultures of the times in which they were written."I definitely think of myself as a philologist specializing in Sinology. Disciplines parallel to Sinology are Indology, Japanology, Semitology, and so forth. For the majority of scholars, these have now morphed into Indian Studies, Japanese Studies, Semitic Studies, and so on, but I'm old fashioned and still cling to the old ideals and old methods of Sinology, though happily assisted now by modern technology and techniques (computers, data bases, online resources, etc.).

Monday, April 21, 2014

Toward a Computational Historicism. Part 1: Discourse and Conceptual Topology

Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.

– Percy Bysshe Shelley

... it is precisely because we are talking about ordinary language that we need to adopt a notation as different from ordinary language as possible, to keep us from getting lost in confusion between the object of description and the means of description.

–Sydney Lamb

Worlds within worlds – that’s how Tim Perper, my friend and colleague, described biology. At the smallest scale we have individual molecules, with DNA being of prime importance. At the largest scale we have the earth as a whole, with all living beings interacting in a single ecosystem over billions of years. In between we have cells, tissues, and organs of various sizes, autonomous organisms, populations of organisms on various scales from the invisible to continent-spanning, and interactions among populations of organisms on various scales.

Literature too is like that, from single figures and tropes, even single words (think of Joyce’s portmanteaus) through complete works of various sizes, from haiku to oral epics, from short stories through multi-volume novels, onto whole bodies of literature circulating locally, regionally, across continents and between them, from weeks and years to centuries and millennia. Somehow we as humanists and literary critics must comprehend it all. Breathtaking, no?

In this essay I sketch a potential computational historicism operating at multiple scales, both in time and textual extent. In the first part I consider network models on three scale: 1) topic models at the macroscale, 2) Moretti’s plot networks at the mesoscale, and 3) cognitive networks, taken from computational linguistics, at the microscale. I give examples of each and conclude by sketching relationships among them. I open the second part by presenting an account of abstraction given by David Hays in the early 1970s; in this model abstract concepts are defined over stories. I then move on to Hauser and Le-Khac on 19th Century novels, Stephen Greenblatt on self and person, and consider several texts, Amleth, Hamlet, The Winter’s Tale, Wuthering Heights, and Heart of Darkness.

Graphs and Networks

To the mathematician the image below depicts a topological object called a graph. Civilians tend to call such objects networks. The nodes or vertices, as they are called, are connected by arcs or edges.

Such graphs can be used to represent many different kinds of phenomena, a road map is an obvious example, a kinship tree is another, sentence structure is a third example. The point is that such graphs are signs of phenomena, notations. They are not the phenomena itself.

Sunday, April 20, 2014

Three cheers for the liberal arts

Tom Friedman to Laszlo Bock, head of hiring at Google:

Are the liberal arts still important?

They are “phenomenally important,” he said, especially when you combine them with other disciplines. “Ten years ago behavioral economics was rarely referenced. But [then] you apply social science to economics and suddenly there’s this whole new field. I think a lot about how the most interesting things are happening at the intersection of two fields. To pursue that, you need expertise in both fields. You have to understand economics and psychology or statistics and physics [and] bring them together. You need some people who are holistic thinkers and have liberal arts backgrounds and some who are deep functional experts. Building that balance is hard, but that’s where you end up building great societies, great organizations.”

Trees: Their use in visualization

Scott Weingart reviews Manuel Lima, The Book of Trees: Visualizing Branches of Knowledge (Princeton 2014:

Lima’s book is a history of hierarchical visualizations, most frequently as trees, and often representing branches of knowledge. He roots his narrative in trees themselves, describing how their symbolism has touched religions and cultures for millennia. The narrative weaves through Ancient Greece and Medieval Europe, makes a few stops outside of the West and winds its way to the present day. Subsequent chapters are divided into types of tree visualizations: figurative, vertical, horizontal, multidirectional, radial, hyperbolic, rectangular, voronoi, circular, sunbursts, and icicles. Each chapter presents a chronological set of beautiful examples embodying that type.

Literary Studies in the Current Era (the Machinic and post-Apocalyptic Anthropocene)

Back in August 2011 I published a short document called Preview: The Key to the Treasure IS the Treasure, A Program for Literary Studies in the Current Era.

In December 2013, after I’d been working on Latour and pluralism for awhile, I published a revised version in which I replaced Object Oriented Ontology from the first version with Ethical Criticism: The Key to the Treasure IS the Treasure.

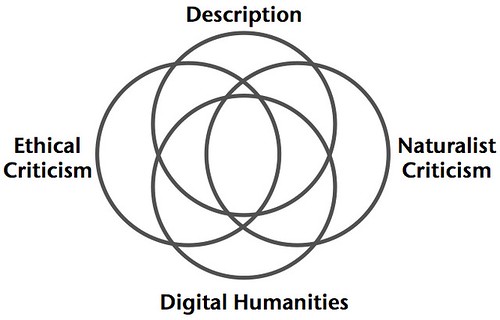

No doubt there will be a third version, perhaps soon, or perhaps a little later. In any event I offer this diagram by way of making the obvious point that the divisions I imagine aren’t exclusive.

For those who haven’t read either of the earlier documents I note two things: 1) I give description separate billing because I believe that we MUST get better descriptive control over our materials. Description as I have come to understand it encompasses both somewhat revised approaches to “close” reading and “distant” reading. 2) Ethical criticism encompasses hermeneutics and critique while naturalist criticism can accommodate cognitive and evolutionary approaches.

I took more or less the first version of Key to the Treasure, added some philosophical reflection, and posted a working paper to SSRN in September 2012: Working Paper: Literary Criticism 21: Academic Literary Study in a Pluralist World. Here’s the abstract:

At the most abstract philosophical level the cosmos is best conceptualized as containing various Realms of Being interacting with one another. Each Realm contains a broad class of objects sharing the same general body of processes and laws. In such a conception the human world consists of many different Realms of Being, with more emerging as human cultures become more sophisticated and internally differentiated. Common Sense knowledge forms one Realm while Literary experience is another. Being immersed in a literary work is not at all the same as going about one's daily life. Formal Literary Criticism is yet another Realm, distinct from both Common Sense and Literary Experience. Literary Criticism is in the process of differentiating into two different Realms, that of Ethical Criticism, concerned with matters of value, and that of Naturalist Criticism, concerned with the objective study of psychological, social, and historical processes.

Saturday, April 19, 2014

Irving Geis: He Saw Molecules

Well, not directly. No one can do that, they’re too small. They’re so small that you can’t even see them with the most powerful light microscope. They’re dimensions are less than the wavelengths of visible light. In effect, light misses them.

So you zap them with a tightly focused x-ray beam – much shorter wavelengths – and the beam scatters onto a photographic emulsion or, these days I guess, on to some micro-electronic detector and get an image. Which looks like a smudge. But, from such smudges you can deduce what the thing must look like.

That’s where Geis came in. He takes those deductions, which have been rendered as sketches of some sort, and turns them into useful and elegant images, images that make sense to the naked eye. These images are at once true to the molecule and to the eye, but they are also fictions. Because, as I said, they’re way too small to be visible themselves. So Geis had to come up with plausible visualization.

Many others have painted molecules, but Geis was the first. You can find nice appreciations at L2Molecule and at Brain Pickings, which covers some of his other scientific visualizations. This Google query pulls up a bunch of images.

Here’s a passage about Geis from an article* I wrote on visual thinking:

In a personal interview, Geis indicated that, in studying a molecule's structure, he uses an exercise derived from his training as an architect. Instead of taking an imaginary walk through a building, the architectural exercise, he takes an imaginary walk through the molecule. This allows him to visualize the molecule from many points of view and to develop a kinesthetic sense, in addition to a visual sense, of the molecule's structure. Geis finds this kinesthetic sense so important that he has entertained the idea of building a huge model of a molecule, one large enough that people could enter it and move around, thereby gaining insight into its structure. Geis has pointed out that biochemists, as well as illustrators, must do this kind of thinking. To understand a molecule's functional structure biochemists will imagine various sight lines through the image they are examining. If they have a three-dimensional image on a CRT, they can direct the computer to display the molecule from various orientations. It is not enough to understand the molecule's shape from one point of view. In order intuitively to understand it's three-dimensional shape one must be able to visualize the molecule from several points of view.

Think about that for a minute. In order to visualize a single tiny molecule, Geis used his entire body.

* * * * *

* William Benzon. Visual Thinking. Allen Kent and James G. Williams, Eds. Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Technology. Volume 23, Supplement 8. New York; Basel: Marcel Dekker, Inc. (1990) 411-427, https://www.academia.edu/13450375/Visual_Thinking.

Friday, April 18, 2014

The Only Game in Town: Remarks on Alan Liu and Digital Humanities

I've collected five posts on Alan Liu into a single PDF. You can download it from my SSRN page: Remarks on Alan Liu and the Digital Humanities, A Working Paper. Abstract and introduction below.

* * * * *

Abstract: Alan Liu has been organizing and conceptualizing digital humanities (DH) for two decades. I consider a major essay, “The Meaning of the Digital Humanities,” two interviews, one with Katherine Hayles and the other with Scott Pound, and a major blog post in which Liu engages Stephen Ramsay. Other investigators included: Willard McCarty and Franco Moretti. Some of Liu’s themes: DH as symbolic of the future of the humanities, the need for theory as well as practical projects, the role of DH in enlarging the scope of the “thinkable,” the importance of an engineering mindset, and the need for a long-term effort in revivifying the humanities.

* * * * *

Computation has theoretical consequences—possibly, more than any other field of literary study. The time has come, to make them explicit.

–Franco Moretti

I first heard about Alan Liu back in the late 1990s, when he was working on Voice of the Shuttle. I may or may not have submitted some links, I don’t really remember, but if so, that would have been it. Since then I gather that he’s been acting as a Johnny Appleseed for what has come to be called digital humanities, an ambassador, or in the corporate jargon of Apple Inc., an evangelist.

But it wasn’t until early in 2012 that I started to focus on the so-called digital humanities (aka DH). To be sure, Matt Kirschenbaum showed up at The Valve (alas, now dormant) for the Moretti book event (Graphs, Maps, Trees) and, for that matter, Moretti himself put in a few appearances. I snagged a promising book reference from Kirschenbaum (Dominic Widdows, Geometry and Meaning), but for me that event was about Moretti, not DH. It took Stanley Fish to get me thinking about DH. He’d gone to the MLA convention, attended some DH sessions, and blogged about it in January, 2012: Mind Your P’s and B’s: The Digital Humanities and Interpretation. Of my posts tagged “digital humanities”, only a bit less than a quarter of them were written before Fish. The rest come after.

Sometime in the wake of Fish I came across anxiety within the DH community about the lack of Theory, with Alan Liu prominent among the worriers. Now I was irritated. On the one hand, it seems to me that Theory has lost most of its energy – for what it's worth, it was an examination of that morbidity that had attracted me to The Valve (the discussions of Theory’s Empire) in the summer of 2005. On the other hand, there’s a rich body of theory around computation, language, the mind, and evolutionary process (read: history) which is relevant, it seemed to me, to DH and yet which has been for the most part neglected. There is more to theorizing humanity than is dreamt of in Theory.

Finally, in March of this year I saw a video of Liu’s Meaning of the Humanities talk at NYU. I watched it, liked it, and contacted Alan. He responded by sending me a PDF of his PMLA article of the same title (“The Meaning of the Digital Humanities”, PMLA 128, 2013, 409-423). That prompted me to write the first of the blog posts I’ve collected here: Computer as Symbol and Model: On reading Alan Liu.

Thursday, April 17, 2014

A digital humanist was walking to Damascus...

I’m wondering how many digital humanists set out to do one thing and ended up realizing they were doing something else, something they don’t quite understand. Some texts...

* * *

We who have been working in the field know that the digital humanities can provide better resources for scholarship and better access to them. We know that in the process of designing and constructing these resources our collaborators often undergo significant growth in understanding of digital tools and methods, and that this sometimes, perhaps even in a significant majority of cases, fosters insight into the originating scholarly questions. Sometimes secular metanoia is not too strong a term to describe the experience.

Willard McCarty, A Telescope for the Mind?

* * *

To Capture Infinity in a Bottle: The Digital Humanities and Cultural Criticism

The Gist: The only way the digital humanities are going to develop a cultural analytics that is sui generis is by thinking about the nature of computation itself in relation to human minds, as embodied in human brains, and as developing though interaction with other minds through various media and in groups of varying size and social structure. Otherwise the digital humanities will have no choice by to borrow its cultural concepts from other discourses, as it is now doing.

* * * * *

Let has start from some passages. First up, Alan Liu, from “Why I’m In It” x 2 – Antiphonal Response to Stephan Ramsay on Digital Humanities and Cultural Criticism (September 13, 2013):

The digital humanities can only take on their full importance when they are seen to serve the larger humanities (and arts, with affiliated social sciences) in helping them maintain their ability to contribute to the making of the full wealth of society, where “wealth” here has its older, classic sense of “well-being” or the good life woven together with the life of good.

Compare that with Willard McCarty, A telescope for the mind? (Debates in the Digital Humanities, ed. Matthew K. Gold. Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2012): “What can the digital humanities can do for the humanities as a whole that helps these disciplines improve the well-being of us all?”

Back to Liu:

It seems to me that digital humanists can and should evolve a mode of cultural criticism that is uniquely their own and not a mere echo of fading humanist cultural criticism by treating their immediate objects of inquiry (academically-oriented technologies and methods) as always also “mediate objects of inquiry” bearing on the way the human beings they wish their students could become (and they themselves could be on their best days) can really engage meaningfully with larger social agents and forces....The goal is to do research, to teach, and to live as if humanities technology is constantly intertwined with, reacts to, and acts on the way the links are now being forged between individuals (starting with those in the academy where we teach and conduct research) and the social-economic-political-technological constitution of contemporary society.What it comes down to is that the digital humanities need both to work on tools and methods in their own institutional place (the academy) and to develop a capable imagination of the relation of that unique institutional place (or family of variant institutional spaces) to the other major institutions that play a part in enabling or thwarting the passageway from private human subjectivity to public social sensibility.

It seems that Liu is imagining a cultural criticism centered on institutions and society, one that treats computers and minds as black boxes whose inner workings remain unexamined. In this practice it seems to me that the ideas about culture and society would likely come from already existing bodies of work.

Wednesday, April 16, 2014

As Greece Founders, Athens Becomes Graffiti Mecca

From the NYTimes:

Graffiti in Athens, as in other cities the world over, has flourished for decades. But in a country where the adversity of wars and military dictatorship already has shaped the national psyche, the five-year economic collapse has spawned a new burst of creative energy that has turned Athens into a contemporary mecca for street art in Europe.Denounced as thuggish vandalism by some observers, but hailed by others as artistic and innovative, tags, bubble letters and stylized paint work long have blanketed this city’s walls, trains, cars, banks, kiosks, crumbling buildings — and even some ruins of the Acropolis. But in the past several years, the anguish of the times has increasingly crept into the elaborate stencil work and multitude of large, colorful murals found all over the city, as Greece’s throngs of unemployed and underemployed young people have ample time to express their malaise.

And a dentist has turned to graff:

Recently, under cover of darkness, a Greek dentist whose business has been all but wiped out by the crisis reached into a tote bag and grabbed a can of spray paint and a stencil he had cut in his spare time using a cavity drill. Stopping at a crumbling wall, he quickly painted an image not typically associated with his profession: a masked man hurling a firebomb.“The middle class and the working class in Greece have been ruined,” said the dentist, who goes by the street handle Mapet, declining to give his real name. “My goal is to deliver social and political counterpropaganda, and make people think.”

Athens School of Fine Arts has courses in street painting.

Tuesday, April 15, 2014

The Gojira Papers

While I've got some more thinking to do about Gojira, I'm currently preoccupied with other things. So I've to decided to take what I've got so far and wrap it up into a working paper. Here's the link to the Academia.edu page. Abstract and introduction are below.

Abstract : Gojira (1954) is a Japanese film with two intertwined plots: 1) a monster plot about a prehistoric beast angered by atomic testing, and 2) a love plot structured around a conflict between traditional arranged marriage and modern marriage by couple’s choice. The film exhibits ring-composition (A B C D C’ D’ A’) as a device linking the two apparently independent plots together. Nationalist sentiment plays an important role in that linkage. the paper ends with a 6-page table detailing the actions in the film from beginning to end.

Machinic Theory and the Humanities Singularity

Back when I threw in my lot with cognitivism in the early 1970s, I did so because I was excited by the idea of computation. That's what animated the early years of the “cognitive revolution.” But, by the 80s you could get on board with the cognitive revolution without really having to think about computation. Computation made the mind thinkable in a way it hadn't been in in the Dark Ages of Behaviorism.

Once that had happened psychologists and others were happy to think about the mind and leave computation sitting off to the side. Among other things, that’s the land of cognitive metaphor, mirror neurons, and theory of minds.

By the mid-90s literary critics were getting interested in cognitive science, but with nary hint of computation. A lot of cognitive criticism looks lot old wine in new barrels. The same with most literary Darwinism. All that's new here are the tropes, the vocabulary.

As far as I can tell, digital criticism is the only game that's producing anything really new. All of a sudden charts and diagrams are central objects of thought. They're not mere illustrations; they're the ideas themselves. And some folks have all but begun to ask: What IS computation, anyhow? When a died-in-the-wool humanist asks that question, not out of romantic Luddite opposition, but in genuine interest and open-ended curiosity, THAT's going to lead somewhere.

If you think of a singularity as a moment where change is no longer moving away from the old, but (now has the possibility of) moving toward an as yet unknown something new, then that's where we are NOW.

Monday, April 14, 2014

From Quantification to Patterns in Digital Criticism

I would like to continue the examination of fundamental presuppositions, conceptual matrices, which I began in The Fate of Reading and Theory. That post was concerned with how, in the context of academic literary criticism, 1) “reading” elides the distinction between (merely) reading some text – for enjoyment, edification, whatever – and writing up an interpretation of that text and 2) how “literary theory” became the use of theory in interpreting literary texts. This post is about the common sense association between computers and computing on the one hand and numbers and mathematics on the other.

* * * * *

Let’s start with a couple of sentences from one of the pamphlets published by Stanford’s Literary Lab, Ryan Heuser and Long Le-Khac, A Quantitative Literary History of 2,958 Nineteenth-Century British Novels: The Semantic Cohort Method (May 2012, 68 page PDF):

The general methodological problem of the digital humanities can be bluntly stated: How do we get from numbers to meaning? The objects being tracked, the evidence collected, the ways they’re analyzed—all of these are quantitative. How to move from this kind of evidence and object to qualitative arguments and insights about humanistic subjects—culture, literature, art, etc.—is not clear.

There we have it, numbers on the one hand and meaning on the other. It’s presented is a gulf which the digital humanities must somehow cross.

When first read that pamphlet most likely I thought nothing of that statement. It states, after all, a commonplace notion. But when I read those words in the context of writing a post about Alan Liu’s essay, “The Meaning of the Digital Humanities” (PMLA 128, 2013, 409-423) I came up short. “That’s not quite right,” I said to myself, it’s wrong to so casually identify computers and computing with numbers.”

* * * * *

Now let’s take a look at an essay by Kari Krauss, Conjectural Criticism: Computing Past and Future Texts (DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly, 2009, Volume 3 Number 4). Here’s her opening paragraph:

In an essay published in the Blackwell Companion to Digital Literary Studies, Stephen Ramsay argues that efforts to legitimate humanities computing within the larger discipline of literature have met with resistance because well-meaning advocates have tried too hard to brand their work as "scientific," a word whose positivistic associations conflict with traditional humanistic values of ambiguity, open-endedness, and indeterminacy [Ramsay 2007]. If, as Ramsay notes, the computer is perceived primarily as an instrument for quantizing, verifying, counting, and measuring, then what purpose does it serve in those disciplines committed to a view of knowledge that admits of no incorrigible truth somehow insulated from subjective interpretation and imaginative intervention [Ramsay 2007, 479–482]?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)