I’d been planning to write this for some time. Having spent a good bit of time over the last month thinking and writing about the toxic relationship Avital Ronell had with Nimrod Reitman [1], it seemed urgent that I tell a story about a different kind of relationship.

* * * * *

I met David Hays in the Spring of 1974, my second semester in graduate school at the State University of New York at Buffalo. I was sitting in the English Department’s graduate student lounge talking with Ralph Henry Reese, a second year student. When I mentioned my interest in cognitive science, and in particular, in cognitive networks, he brought out this cognitive network diagram he’d been working on. It was for buried treasure stories. He’d been working with this guy in Linguistics, David Hays. He was a computational linguist. The name rang a bell.

Didn’t he write that article in Dædalus [2], about language and love? I didn’t know he was here at Buffalo. That was a good article, the best in the issue.

And so I met Hays in his office and explained what I was up to. We talked about cognitive science I suppose, because that’s what I was there for, and about my specific problem: I’d found this formal pattern in “Kubla Khan” that smelled like computation – I’m not sure I used that word, “smelled” in that first conversation, but it did come up early in our conversations. There was nothing in literary criticism that gave me a clue as to what it was about and no one in the English Department who could really help me, though they liked the work. Perhaps he would read my MA thesis on the poem and let me know what he thought? He agreed and I left him with a copy of the thesis.

I returned a week or two later and we talked. Have you tried this? Yes, I said. Didn’t get me anywhere. What about this? Same thing. He was impressed, thought there was something there, but just what...We decided to work together, teacher and student.

* * * * *

I enrolled in a graduate seminar Hays was giving that fall, “Language as a Focus for Intellectual Integration.” The rubric was a flexible one, basically a vehicle for Hays and his students to investigate whatever interested them. Each student could suggest a book or two. I remember Hays had us read William Powers, Behavior: The Control of Perception, and Talcott Parsons, The Structure of Social Action. I’d offered Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Raw and the Cooked, and Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism. I forget what else we read. The class format was simple, weekly readings, discussion in Hays’s office (there weren’t but a handful of students enrolled), and a final paper.

At the same time Hays tutored me in his semantic theory. He’d written a book, Mechanisms of Language, for a course of the same name, in which he set out his best account of language, phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics. He never published it formally; rather the Linguistics department arranged to make copies of the typescript for distribution in class. He gave me a copy. We concentrated on semantics, which was more or less independent of the other material.

We met once a week at my apartment. We sat around the kitchen table because we needed to be able to draw diagrams. Hays’ theory was very visual. We used up a lot of paper.

Why my apartment? Convenience mostly. SUNY Buffalo had just opened a new suburban campus. The Linguistics Department had moved there, but the English Department had not. The English Department remained in north Buffalo and I lived near the department. Hays would come by my apartment on the way to his office at the new campus – on seminar days I commuted to his office by shuttle bus.

At the beginning of the semester I’d asked Hays how long he thought it would take me to learn the semantic model. Why’d I ask that? I don’t know, vanity, eagerness, who knows. I asked. He said it generally took two to three months. Thought I to myself, it won’t take ME that long. And you know what? Three months. Back and forth across the kitchen table, working exercises from Mechanisms, talking, drawing diagrams. It was like math. It WAS math, albeit of an informal kind. You had to work the problems. That was the only way.

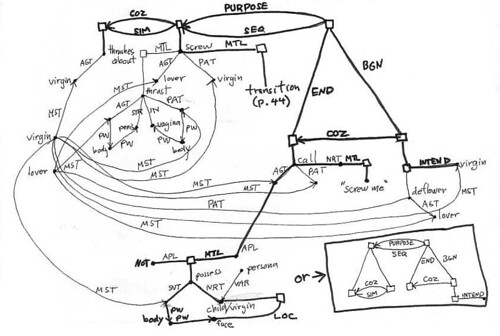

At the end of those three months I took what I’d learned in those tutoring sessions and applied it to some fragments of William Carlos Williams’ Patterson, Book V, which I’d been studying in a poetry seminar taught by Charlie Altieri. The result was a long paper which I submitted to both seminars, Modern Poetry and Linguistics as a Focus of Intellectual Integration. Here’s a diagram from that paper:

That’s what took me three months, maybe four, to learn. It’s not just the diagrams themselves, what the labels (COS, SIM, BGN, MTL, NRT, etc.) mean and so forth, but how to go from natural language statements to these diagrams representing the underlying semantic structure. It’s the back-and-forth between language and diagrams that takes time to learn, to internalize.

* * * * *

At the same time Hays was holding research meetings at his home, which was a bit south of Buffalo in Wanakah on the eastern shore of Lake Erie. The meetings were open to anyone who had something they wanted to discuss before the group, but it was mostly graduate students. Some undergraduates attended and occasionally another faculty member.

The format was simple: At the beginning of the meeting each person could put an item on the agenda. We then went through the items one by one. I don’t recall how the order was decided, but I suspect that we just went around the table. If we were unable to finish an item, or if someone’s item didn’t make it to the floor before the end of the discussion, those items went to the top of the list for the next session.

We got a lot accomplished in those meetings. Real work. Problems were stated, discussed, and solutions were proposed and accepted. Not always, mind you, but often enough.

One reason things worked so well is that everyone in the seminar was familiar with Hays’s work and, for the most part, discussion centered around it. This wasn’t an absolute requirement, and other topics in linguistics and cognition were brought up. But for the most part we were working with and extending the ideas Hays had put into Mechanisms of Language. That gave us a common language.

It was exciting. Real intellectual work, accomplished cooperatively, in a group. That’s how it should be.

And yet the work session, the discussions around the dinner table, the diagrams on the white board, that was only one half of a meeting. The other half consisted of a communal meal. We usually held the work sessions in the afternoon, though sometimes there was a morning session.

Before or after the work session we’d prepare a meal. Hays would let us know what was available in the kitchen – he usually had some idea of what was to be done – and we’d make a meal of it. After the meal we’d clean up and wash the dishes. Of course we’d be talking all the while, sometimes about the intellectual work, “the theory”, but also about current affairs, music, movies, whatever.

Hays believed the fellowship of the meal, which we’d prepared together, was important to the (educational) process.

* * * * *

And so things went believe into the summer or 1975. Hays had a sabbatical in the fall and suspended the research meetings for that period. But I continued to work with him.

He was editor of The American Journal of Computational Linguistics and I had become the journal’s bibliographer (a paid position), a job I inherited from Brian Phillips, who’d just graduated. The journal came out quarterly. It was my to prepare abstracts of the current literature, journal articles and technical reports. Given Hays’ interdisciplinary impulses, that had me reading widely in computational linguistics, linguistics, computer science, artificial intelligence, library science and informatics, and cognitive science.

Hays wanted informative abstracts rather than merely indicative abstracts. A proper informative abstract gave you the may substantive result such that, if you were in a hurry, didn’t need a lot of detail, and trusted the journal, you didn’t have to read the whole article. The abstract told you all you needed. Alas, many articles and tech reports didn’t have proper informative abstracts. My job was to read through the article and write one. When it was time to assemble an issue [3] I’d go to Hays’ house and type up the abstracts on his IBM Selectric typewriter – which was, at the time, the best typewriter available.

At some point after I’d been doing this for awhile Hays was asked to review the computational linguistics literature for Computers and the Humanities. Since I’d been buried in the literature for awhile he asked me to draft the essay, which I was glad to do, of course. He read it, commented, we chatted and...I don’t remember how the final draft got done. Did I write it, did he, I don’t know. But we did it and it was accepted: William Benzon and David Hays, “Computational Linguistics and the Humanist”, Computers and the Humanities 10, 1976, pp. 265-274 [4].

* * * * *

That wasn’t the end of our relationship, not by a long shot. I got my degree two years later and took a job at RPI, failed to get tenure, and did this and that, sometimes making money, sometimes not. Hays and I continued our relationship, which had become an intellectual collaboration. Over the years we co-signed a few more papers, papers that required hours of close conversation over months and years.

Every few months I go to New York City – he left Buffalo in about 1980 or so – and we’d work. We’d talk, draw diagrams as needed, and at some point we’d reach an impasse. The problem wasn’t solved, but we couldn’t figure out how next to proceed. Then, as I noted in my eulogy in 1995 [5]:

Each of us would lie back and drop into fitful reverie. Every so often one of us would make a comment or ask a question. The other would reply, to no mutual satisfaction, and the fitful reverie would continue. Eventually we would work through it, begin talking and talking, and Dave would sit down to the computer and write up some notes on what we had accomplished.

There is one feature of our conversation that is very important: We were careful to acknowledge who had had what idea. It’s not entirely clear to me just why we did it. It certainly wasn’t competitive score keeping. If anything it was cooperative score keeping, for our intellectual work was certainly a cooperative endeavor.

We had different intellectual skills and backgrounds. He had math skills that I did not; I was better at certain kinds of qualitative analysis. He knew the social sciences and linguistics; I knew music and literature. And so forth. This theory, these models we were building, was woven from our disparate and complementary skills and knowledges. When we acknowledged responsibility for an idea, we were marking the junctures between us, the points of connection. Those acknowledgments were at one and the same time courtesies and seams, social acts, and intellectual craftsmanship. You couldn’t, wouldn’t, have one without the other.

* * * * *

[1] See my working paper, Star struck and broken down: Reflections on the case of Avital Ronell, Nimrod Reitman, and the rest, September 2018, https://www.academia.edu/37444542/Star_struck_and_broken_down_Reflections_on_the_case_of_Avital_Ronell_Nimrod_Reitman_and_the_rest.

[2] Hays, D. G. (1973). “Language and Interpersonal Relationships.” Daedalus 102(3): 203-216.

[3] For more about the journal, see my working paper, Personal Observations on Entering an Age of Computing Machines, November 2015, pp. 6-9, https://www.academia.edu/18791499/Personal_Observations_on_Entering_an_Age_of_Computing_Machines.

[5] How Now I and Thou: In Memory of David Glenn Hays, New Savanna, http://new-savanna.blogspot.com/2011/04/how-now-i-and-thou-in-memory-of-david.html.

No comments:

Post a Comment