I'm currently thinking about Harold Bloom and his Bardolatry. Thus I'm bumping this post to the top of the queue as it is directly relevant. The following post is relevant as well: What does evolution have to teach us about Shakespeare’s reputation? [founder effect].

* * * * *

Yes, I know, all those plays were written by a real person, not by an alien from another world. And no, I’m not alluding to that inane controversy over whether or not those plays were in fact written by Christopher Marlow, Edward de Vere, or Rocket J. Squirrel. I’ve got something else in mind.

I’m thinking of his place in our cultural imagination. There he’s an almost mythic figure, beyond any mere human being. He’s the best, no one else is even close. That’s the legendary creative genius whom Harold Bloom credits with creating well, hear him out [1]:

Western psychology is much more a Shakespearean invention than a Biblical invention, let alone, obviously, a Homeric, or Sophoclean, or even Platonic, never mind a Cartesian or Jungian invention. It’s not just that Shakespeare gives us most of our representations of cognition as such; I’m not so sure he doesn’t largely invent what we think of as cognition. I remember saying something like this to a seminar consisting of professional teachers of Shakespeare and one of them got very indignant and said, You are confusing Shakespeare with God. I don’t see why one shouldn’t, as it were. Most of what we know about how to represent cognition and personality in language was permanently altered by Shakespeare.

Is The Bard great? Of course. But is he THAT good, that original, all by his own self? I think not. Actually it’s not so much that but that I don’t know what all those superlatives mean. Still, it’s useful to have him around, as many legends are.

Popularity/Prestige

And that brings me to J.D. Porter, Popularity/Prestige, from Stanford’s Literary Lab [2]. It’s about the so-called canon and it’s relation to non-canonical texts. As the title suggests, it’s about the roles of popularity and prestige in determining canonicity.

The study uses a convenience sample of 1406 authors. It is not nor is it intended to be comprehensive. It is biased toward the English language. Porter measured popularity by counting the number of times an author was rated on the Goodreads website and prestige by the counting number of articles in the MLA International Bibliography where the author is listed as “Primary Subject Author”.

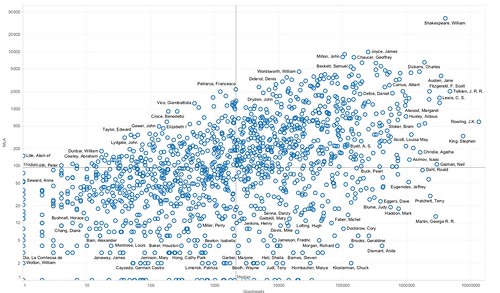

Consider this graph:

Popularity is indicated along the X axis (Goodreads) while prestige is indicated along the Y axis (MLA). That figure way up there at the Northeast corner, that’s Shakespeare, all alone.

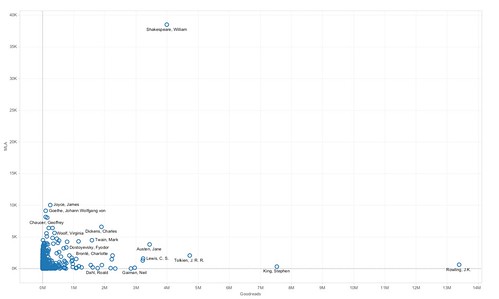

The thing to realize is that the chart scales are logarithmic. When you plot the same data without logarithmic scaling Shakespeare’s uniqueness pops out even more dramatically:

Almost all the other authors are bunched together down there at the Southwest corner. Only about 40 authors escape the “blob”, as Porter calls it. That’s Shakespeare up there at the top, with almost four times as many articles (38,000) as the next-most prestigious author, James Joyce with 10,000 articles. This chart also makes it obvious that there are three authors who make more appearances in Goodreads: J.R.R. Tolkien, Stephen King, and J.K. Rowling. King and especially Rowling have vastly more readers than Shakespeare, but none of those three have anything like Shakespeare’s prestige.

Why the enormous difference in prestige? Well, I suppose one could say that Shakespeare’s THE BEST, and hence better than Tolkien, King, and Rowling. But that doesn’t quite get at it. I’m willing to concede that he’s better than those three, and better than most other writers as well. As to whether or not he’s the BEST EVER, I’m not sure that’s even a meaningful designation.

But why does Shakespeare have overwhelmingly more articles about him than any writer? I don’t really know, but I have a few remarks. Obviously any academic who’s a Shakespeare specialist is going to write articles about him. And so it is with specialists in the Early Modern period, particularly specialists in British literature. The same goes for specialists in drama, in the sonnet, and so forth. But how is it the he came to be an exemplary author, one you’re likely to write about if you want to make a general theoretical or methodological point independently of any specific area of specialization? It helps, of course, that he wrote several centuries ago. It’s not only that age tends to confer prestige, but that it affords more time for sprouting influence. Beyond that, how is it that he came to be included in general survey courses such as world literature or British literature? Has Shakespeare's presence in all those survey courses in turn driven his popularity?

But all those articles are relatively recent, within a century or so. What got Shakespeare the level of visibility such that, when scholars started publishing articles, they published them about Shakespeare? Whatever it is, once it got started, it snowballed, and Shakespeare took over the academic field. And now he’s untouchable.

For awhile.

How will things look 100 years from now?

The canon system

Put in an extreme way, which I don’t necessarily believe but I’m putting it this way so we can see the internal logic, let’s assume that a canon system, if you will, requires a centerpiece, one significant author (or text), to anchor the whole thing. This is a structural requirement. Think of it like the solar system: one sun, a bunch of planets, planetoids and asteroids, and some of those planets can have their own satellites. The system functions to keep everything in its place.

Yes, I know, there are double star systems. That’s a complication. Set it aside.

Where does that centerpiece come from? First answer: It doesn’t matter; perhaps it’s an accident. Once a text is fixed in the center, the system will function to keep it there. Second answer: It’s motivated. The centerpiece is noticeably different from its competitors.

If Shakespeare’s position is in fact motivated, I think the motivation would be some combination of the quality of his poetry and the variety of his dramatic materials. Once he got fixed in the center role, the system kept him there, where he still is.

What are the institutions of this system? Well, no doubt it varies. The Early Modern world is institutionally different from the Modern world. For example, the aristocracy was much more important in the early modern world than it is in the modern world. Different levels of literacy are a factor as well; Porter wonders whether or not “prestige and popularity [are] even distinct in, say, 1650, when most people could not read” (p. 19). In the modern world we have the emergence of mass literacy, which confers power on those who control print media. It also confers power on the school system, libraries, and colleges and universities.

What institutions are responsible for the current canon system, when did they emerge, and what was Shakespeare’s standing when that happened?

Note: This was suggested by the rocket/airplane metaphor Porter invokes on page 21.

There's more

Literary Lab Pamphlet 17 isn’t primarily about Shakespeare’s oddball status. While Porter acknowledges that status (pp. 14 and 15) they don’t dwell on it. Rather, they discuss how complex the literary field is and how canonicity changes over time. The whole thing is well worth reading.

References

[1] Antonio Weiss, interviewer, “Harold Bloom, The Art of Criticism No. 1”, The Paris Review, No. 118, Spring 1991, https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2225/harold-bloom-the-art-of-criticism-no-1-harold-bloom.

[2] J.D. Porter, Popularity/Prestige, Pamphlet No. 17, Stanford Literary Lab, September 2018, https://litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet17.pdf.

No comments:

Post a Comment