Another working paper (title above):

Academia.edu: https://www.academia.edu/10263479/Cultural_Evolution_Literary_History_Popular_Music_Cultural_Beings_Temporality_and_the_MeshSSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2553278

Abstract and introduction below.

* * * * *

Abstract: Culture is implemented in a material and biological substrate but has a distinct ontology and its phenomena belong to a distinct order of temporality. The evolution of culture proceeds by random variation among coordinators, the cultural parallel to biological genes, and selective retention of phantasms, the cultural parallel to biological phenotypes. Taken together phantasms and a package or envelope of coordinators constitute a cultural being. In at least the case of 19th century American and British novels, cultural evolution has a direction, as demonstrated by the analytical work of Matthew Jockers (Macroanalysis 2013). While we can think of cultural evolution as a phenomenon that happens in history, it is at the same time a force that influences human life. It is thus a force IN history. This is illustrated by considering the history of the European novel from the 19th century and into the 20th century and in the evolution of popular musical styles in 20th century American music, in which interaction between African American and European American populations has been important. Ultimately, the evolution of culture can be thought of as the evolution of mind.

* * * * *

0. Introduction: The Evolution of Culture is the Evolution of Mind

One of the themes that has been prominent in Western culture is that we humans have a “higher” nature and a “lower” nature. That lower nature is something we share with animals, even plants–I’m thinking here of Aristotle’s account of the soul. That higher nature is unique to us and we have tended to identify it with reason and rationality. We are rational and can reason, animals are not and cannot.

It was one thing to hold such a belief when we could believe that our nature was distinct from that of animals. Darwin made that belief much more difficult to entertain. If we are descended from apes, and so are but animals, then how can we have this higher nature? And yet, by any reasonable account, we are quite different from all the other animals.

For one thing, we have language. Yes, other animals communicate, and, with much painstaking effort, we’ve managed to teach some sign language to chimpanzees, but still, no other species has yet managed anything quite like human language. And the same goes for culture. Yes, other animals have culture in the sense that they pass behavioral traits from one individual to another through social learning rather than through reproduction. But the trait repertoire of animal culture is quite limited in comparison to that of human culture. Nor has any animal species managed to remake their environment in the way we have, for better or worse, not beavers and their dams, nor termites and their often astounding mounds.

In the process of working through the posts I’ve gathered into the this working paper, the original writing and the subsequent reviewing and revising, I’ve come to believe that it is culture, not reason, that is our higher nature. Reason is a product of culture, not the reverse.

That conclusion is not a direct result of the post’s I’ve gathered here. You won’t find it as a conclusion in any of them, nor will I provide more of an argument in this introduction than I’ve already done. It’s a way of framing my current view of culture and human nature. It’s a higher nature. It rules us even as it is utterly dependent upon us.

Conceptualizing Cultural Evolution

This working paper marks the fruition of a line of investigation I began in 1996 with the publication of “Culture as an Evolutionary Arena” (Journal of Social and Evolutionary Systems, 19(4), 321-362). That was not my first work on cultural evolution; but my earlier work, going back to graduate school in the 1970s, was about stages conceived in terms of cognitive systems (called ranks). That work was descriptive in character, aimed at identifying the types of things possible with a given cognitive apparatus. The 1996 paper was my first attempt at characterizing the process of cultural evolution in evolutionary terms.

That paper originated in conversations I’d had with David Hays, who died in 1995, in which he suggested that the genetic material for cultural evolution was in the external world. Why? Because it is public, open for everyone to see. If the genetic material was out there in the world, I reasoned, then the selective environment must be social, something like a collective mind. That made sense because, after all, isn’t that how books and movies and records survive? Many are published, but only a few are taken up and kept in active circulation over the years.

That’s not much of a conception, but I stuck with it. It’s taken almost two decades for me to refine those initial intuitions into a technical conception that feels good. That’s what I managed to achieve in the process of writing the posts I’ve collected and edited into this working paper.

All of which is to say that I’ve been working on two levels. On the one hand I’ve been making specific proposals about specific phenomena. But those specific proposals are in service of a more abstract project: crafting a framework in which to conceptualize cultural evolution. By way of comparison, consider chapter eleven of Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene. That’s where he proposes the concept of memes in thinking about cultural evolution: “Memes: the new replicators” (pp. 189-201). He gives a few examples, but mostly he’s focused on the concept of the meme itself. The examples are there to support the concept. None of them are developed very extensively or in detail; he says just enough to give some sense of what he has in mind.

THAT’s what I’m doing, though proportions and quantities are different. It is the concept of cultural evolution that most interests me: what’s it like, what kind of entities does it involve? The example from Matthew Jockers’ Macroanalysis in the first two posts is just that, an example. In subsequent posts I introduce further examples, but they are just that, examples.

It is important that I treat these examples carefully. But it is not so important that I get them just right. In fact, that is likely all but impossible. For all the discussion there has been on cultural evolution over the last three decades, the area is still in preliminary stages of conceptualization. We still don’t know quite what we’re talking about. So we have to propose concepts and models, try them out to see how they feel, and then re-evaluate.

I’ve been doing that for two-decades now. Some of that work is directly reflected in this collection of posts, but only some of it. I’ve got other examples in other documents, that paper I mentioned in my first paragraph, my 2001 book on music, Beethoven’s Anvil, and others. Taken all together, however, the lot of it doesn’t add up to a strong argument about how things have happened. That’s the wrong level, that’s about specific proposals about specific documented phenomena.

Rather, what I’m offering is a well-thought out set of concepts to be used in studying cultural evolution. None of these proposals is offered without reason, but I don’t claim that any of them is the inevitable conclusion of an ironclad deductive argument. I claim only that they are reasonable and reasonably clear. Further more, this framework is not in competition with some consensus view; it is in competition with other frameworks, none of them fully worked out, but each with its own band of followers.

This working paper starts in dangerous territory, with the idea that cultural evolution has a direction, an idea that is anathema to many biological evolutionists and that is problematic for many humanists, both of which are spooked by the specter of non-existent teleology. I’ve believed that for a long time, but it is only recently that Jockers did his study of 19th century novels. My argument takes the form of a reinterpretation of his work. He set out to investigate the influence that earlier writers exerted on later writers. I argue that what he achieved in fact amounts to a demonstration of directionality. It’s not merely that some writers came later than others, but that the temporal distance between two texts is roughly proportional to their distance between one another in the ‘design space’ of the novel. The trajectory of similarity doesn’t circle back or zig-zag; it goes straight in one direction. That argument gives us the first two sections of this working paper.

In subsequent posts I introduced my own examples, 20th century novel and popular music; that’s three more sections (three, four, and five). That argument led me to thinking about the nature of time, section six: Literary History, Temporal Orders, and Many Worlds. While that’s something I’ve thought about from time to time, I hadn’t expected to run into this time out. Once I did I saw no choice but to, once again, rethink cultural evolution from top to bottom.

And so I began thinking about the basic entities involved, the cultural analogues to the genes and phenotypes of biology. I have, of course, been thinking about those things for years, ever since that 1996 article. But I hadn’t introduced those concepts into the early posts in this series, that ones the make up sections one through six of this working paper. So I wrote two or three relatively short posts on this matters which I have somewhat revised into section seven of this working paper: The Construction of Cultural Beings. That’s where I introduce not only the concept of cultural beings (which I will return to in this introduction) but also the concepts of phantasm, as the cultural analog to the phenotype, and of coordinators, as the cultural analog to genes.

I then return to my examples from literature and music and work through them again, this time in terms of pleasure and anxiety as motivating forces in cultural evolution. I’d covered them before in this series, anxiety especially (section four, Culture as a Force in History). This time the discussion is more complete and subtle.

In some sense, this is the most important conceptualization, and also the most, shall we say, tentative. I devoted a chapter to pleasure and anxiety in Beethoven’s Anvil, and I’d discussed those matters in the 1996 paper, Culture as an Evolutionary Arena. What I’m arguing is that culture evolves because we find anxiety uncomfortable and we seek pleasure. Anxiety has many causes and pleasure has many sources, but I see no choice but to treat both as a property of overall neural flow. That’s what drives us. That’s what mind is.

The Workings of Mind in the Mesh: Master-Slave

To say that it is mind that drives cultural evolution sounds a lot like nineteenth century ideas of Geist, of Spirit. The difference, though, is that I can explicate the idea in terms of material brains interacting with one another in social groups.

I devoted three chapters of my book on music, Beethoven’s Anvil, to that, chapters two, three, and four, on interpersonal coupling, dynamics, and pleasure respectively. Early in the fourth chapter I began explicating the relationship between mind and brain (pp. 71-72; cf. my post The Mind is What the Brain Does, and Very Strange):

Rather than wonder how the mysterious and ineffable mind can connect with the mysterious but concrete brain, I propose a definition:

Mind: The dynamics of the entire brain, perhaps even the entire nervous system, including the peripheral nervous system, constitutes the mind.

The thrust of this definition is to locate mind, not in any particular neural structure or set of structures, but in the joint product of all current neural activity. As such the mind is, as Ryle argued, a bodily process; in the words of Stephen Kosslyn and Olivier Koenig, “the mind is what the brain does.” Whether a neuron is firing at its maximum rate or idling along and generating only an occasional spike, it is participating in the mind. In asserting this I do not mean, of course, to imply that there is no localization of function in the brain. There surely is. But the mind and the brain are not the same thing, though they certainly are intimately related, as are the dancer and the dance. The fact that the dancer is segmented into head, neck, trunk, and limbs does not mean that the dance can be segmented in the same way. Similarly, we should not think of the functional specialization of brain regions as implying a similar specialization of the mind. It is not at all clear that the mind has “parts” in any meaningful sense.

In nudged that conception toward psychoanalysis in a recent post, Neural Weather, an Informal Defense of Psychoanalytic Ideas:

The brain consists of some 100s of neurofunctional areas. Enormous time and effort has gone into figuring out just what each area does and how it relates to what goes on in other areas. Much of this thinking seems like it follows from a vision of a Kafkaesque bureaucracy in which each neurofunctional area is a separate office. These offices receive messages written on scraps of paper sent around through pneumatic tubes. A functionary receives a bunch of such scraps at his desk, reviews them, and writes this or that on fresh scraps which he then sends out through tubes taking them to other anonymous functionaries. This is called information processing.

The thing is, those 100s of neurofunctional areas are each composed of millions upon millions of neurons, each of which is directly connected to 10,000 or so other neurons. Some of those neurons are connected to immediately adjacent neurons; others are connected to more distant neurons in the same neurofunctional area; and many others are connected to neurons in other neurofunctional areas, some close by, some quite distant. If two neurons don’t share any direct connections, chances are they are indirectly connected by multiple chains, some of them of only two or three links, others of five or six links.

Whatever the brain IS, it IS NOT an information-processing bureaucracy.

In my own work I’ve used the metaphor of weather, the mind as neural weather. Think of the brain as a complex landscape and the mind as the swirls and eddies of air, water, and dust blowing through it. And think of defense mechanisms as forms of neural weather. Denial, projection, dissociation, repression, sublimation, and all the rest, they’re complex patterns of activity each involving the whole brain. This, it seems to me, is one area where psychoanalytic thought is going to prove out.

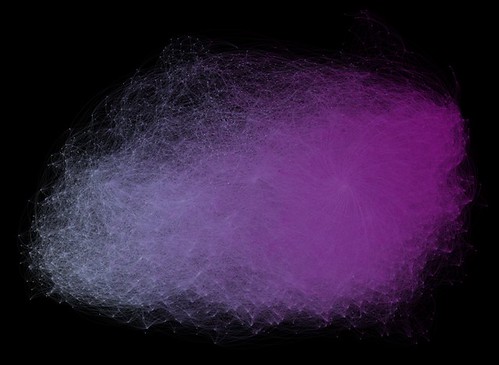

THAT is what Jockers is looking at in this image depicting similarity relationships among nineteenth century novels:

That’s a highly abstracted representation of collective denial, projection, dissociation, repression, sublimation, and the rest; that’s the evolving mind of nineteenth century America and Britain as seen through its production of novels.

When I talk of cultural beings–as I do in section seven, The Construction of Cultural Beings–I mean a physical ‘text’, whether it consists of marks on paper, sounds in the air, or some other subtle deformation of matter, plus its neural trajectory, its mental weather, in the mind/brain of everyone who has experienced it. The phenomenon Jockers has depicted in that image is the evolution of collective neural weather as inferred from the texts of 3346 novelistic cultural beings. To be sure, all he has been working from is the physical texts, he has no access to the minds of those millions of nineteenth century readers. But the order in which those texts were written, that is a function of those tens and hundreds of millions of readings by those millions of readers: millions of readers, billions of readings, 3346 cultural beings.

THAT’s a very abstract conception, but its connections to the mateiral lives of nineteenth century American and British readers are not, in principle mysterious. They can be traced through a Latourian actor network extenting from Jockers and his computers back through libraries to readers, booksellers, publishers, and writers. When I talk of the mesh, that’s what I mean, a Latourian actor network. Cultural evolution is the workings of mind in the mesh.

Those cultural beings, beings anchored in texts and extended through the minds of people participating in those texts, they are utterly dependent upon us. Without us Moby Dick is a bunch of ink splotches on paper and “Take the A Train” is grooves on wax, both of which have become bits in some electronic medium. At the same time we are utterly dependent on these cultural beings as vehicles for our common values, attitudes, and ideas. It looks rather like the master-slave dialectic, though I hesitate to say which is the master, which the slave.

And that higher nature that we’re always invoking to differentiate ourselves from animals, it’s not reason. It’s culture. Yes, there is animal culture, but not to the scale and depth of human culture. Human culture is our higher nature and reason is but one manifestation of it, one that varies from group to group. Culture, our higher nature evolving in the mesh.

* * * * *

Let me remind you that this really is a working paper. There are redundancies in the text and, of course, things that could be spelled our more fully. I say this, not to make excuses, but simply to note that I am aware of the unpolished state of the text. I have been doing this long enough to know that, at this point however, the best thing for me to do is set this project aside for a while. But, as Arnold Schwarzenegger said at the end of The Terminator, I’ll be back.

No comments:

Post a Comment