On the one hand this is one of the more popular posts at New Savanna. Not in the very top rank, but well over a thousand hits. That's one reason to bump it to the head of the queue. The fact that I'm currently thinking about chiasmus, in the extended form known as ring-composition, is a better one.* * * * *

Some years ago, before I got a computer, I read. R. G. Peterson, Critical Calculations: Measure and Symmetry in Literature (PMLA 91, 3, May 1976: 367-375). It opens:

That such a superb example of Renaissance elegance and grace as Spenser’s Epithalamion is literally informed by a complicated numerical system and a highly symmetrical structure was announced in 1960 by A. Kent Hiatt. The numbers–365 days, twenth-four hourse, the proportions of day and night at the summer solstice at a given latitude in Ireland, the long and short lines of the poems, the groups of stanzas–coincide with transitional points in the content; the structure depends upon correspondences and parallels between the two halves.

Peterson goes on to report that similar methods “have been used to reveal everywhere in literature hitherto hidden symmetries, correspondences, patterns, and systems of number symbolism.” He goes on to review quite a bit of this work while raising the inevitable question: did the authors actually intend these patterns? And that question bleeds into this one: Are they real?

The questions are real, and serious. But I’m not prepared to address them in full. I’m interested in a single case. Peterson devotes some attention to Cedric H. Whitman’s study, Homer and the Heroic Tradition (1958) and tells us that had also remarked that Dylan Thomas’ “Author’s Prologue” formed a “huge chiasmus” – that is, the first line rhymed with the last, the second with the next to last, the third with the next to the next to last, and so forth. I decided to check it out.

Rhyming the Circle

“Author’s Prologue” is the first poem in Thomas’ Collected Poems. It is 102 lines long. Here’s the first ten lines:

This day winding down now

At God speeded summer's end

In the torrent salmon sun,

In my seashaken house

On a breakneck of rocks

Tangled with chirrup and fruit,

Froth, flute, fin, and quill

At a wood's dancing hoof,

By scummed, starfish sands

With their fishwife cross

Gulls, pipers, cockles, and snails,

There’s no rhyme scheme apparent there, but that’s not the issue. What we’re interested in is the relationship between the first ten lines and the last ten. Before we look at that, however, let’s look at the middle ten lines:

Out of the fountainhead

Of fear, rage read, manalive,

Molten and mountainous to stream

Over the wound asleep

Sheep white hollow farms

To Wales in my arms.

Hoo, there, in castle keep,

You king singsong owls, who moonbeam

The flickering runs and dive

The dingle furred deer dead!

There the chiasmus begins to reveal itself, as line 51 – Sheep white hollow farms – gives way to line 52 – to Wales in my arms – and then “keep” at the end of 53 resonates back to “asleep” at the end of 50, “moonbeam” back to “stream” and so on beyond the ken of one’s mental resonaters.

Thus it comes a no surprise, to those who check, that the last 10 lines do indeed rhyme with the first 10 in proper symmetcial fashion:

Cry, Multiudes of arks! Across

The water lidded lands,

Manned with their loves they'll move

Like wooden islands, hill to hill.

Huloo, my prowed dove with a flute!

Ahoy, old, sea-legged fox,

Tom tit and Dai mouse!

My ark sings in the sun

At God speeded summer's end

And the flood flowers now.

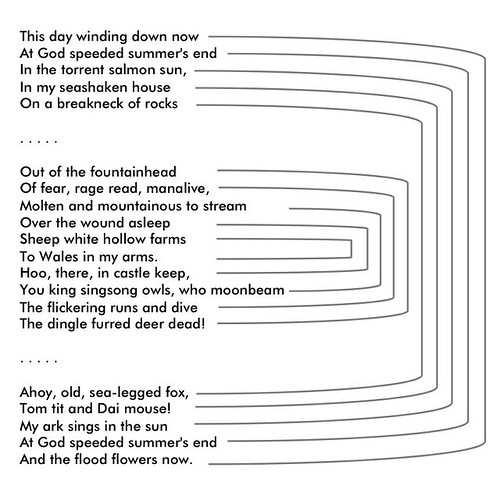

All the other rhymes line up according to scheme I assure you. I’ve checked. Here’s what it looks in diagram form:

It’s quite astonishing when you think about it. And it gets even more astonishing when you look at line lengths. A few lines lay fairly long on the page (e.g. “You king singsong owls, who moonbeam”) while others are short (e.g. “To Wales in my arms.”); the difference is sufficient to be quite visible. And if you look at chiasmic pairs, the line lengths in each pair seem roughly the same. Just look at how those lines lay on the page. Is the whole poem like that?

I think so. Not perfectly so, but close enough to be interesting and intriguing. You can see for yourself. I’ve listed the chiasmic pairs at the end of this post. Examine the list.

A Note on Method

There is a little lesson in method here. I’ve known about that chiasmus for years and verified it for myself long ago. That’s all I had in mind when I set out to write this post. It wasn’t until I’d prepared the above diagram that I noticed the line-length symmetry. Once I saw it there I had to verify it for the entire poem.

Point the first: Description isn’t rocket science. But it’s not self-evidently easy either. You have to be careful and meticulous and, yes, you’ve got to mess around a bit as well. That diagram wasn’t necessary. The point had been made without it. But I like diagrams and I thought the sight of those nested brackets would be pleasing. As indeed it is. The line-length business was a gift from the gods. It’s also another thing to check for in later work.

Point the second: Nothing in cognitive science told me to do any of this and, as far as I know, cognitive science has little to say about why poets do such things. I did it–verified the existence of the chiasmus, did the diagram, and then verified line-length symmetry–because I am an experienced critic. I’ve read many texts (and watched many movies). Though I’ve only done detailed work on a handful of texts (and movies), that’s been sufficient to tell me that these are complex objects and they do not yield their secrets casually.

At any given time you may be looking for something in particular, but you have to keep your antennae tuned to pick up new signals. Years ago I read Theodor Reik on the kind of free-floating attention required of a psychoanalyst in session. Literary critics on the descriptive trail need it too.

But Is It Real?

In this case, of course it is. That’s why I chose it as an example. Such elaborate designs do not happen by accident. That chiasmus is there because Thomas consciously and deliberatly put it there.

But how do I KNOW that he did so consciously and deliberately? I, that is me, persoanlly, don’t know that. I’m assuming it based on my general knowledge of language, the mind, and poets.

There is, however, in this case, more evidence available, evidence I wasn’t aware of until I went cruising online. If you haven’t already done so, look at Thomas’ numbering down the right hand side in the typescript that’s available online. He numbers the lines from five through 50 (at five line intervals) in the first half and then reverses the order for the second half, 50 through five (those numbers aren’t in the published text, at least not the one I havew). That’s conscious intent.

Such evidence isn’t always available. Whoever Homer was, or whoever it was that was on the Homeric Committee for the Presevation of Ancient Tales, didn’t leave any notes about how the two epic poems were constructed. And so it is for many texts.

Thus we find ourselves back at that old question: authorial intention. Any kind of pattern can be created by someone who consciously sets out to do so. That’s why the question of authorial intention has been so important. It’s been taken as an index of textual reality. Texts are complicated objects; they have many different properties and attributes. Which of them are real and which are products of the critical imagination? If the author put it there, consciously and deliberately put it there, then it’s real. Otherwise…

But the question of authorial intention has mostly been directed at matters of meaning, not form. It’s meaning that Stanley Fish, for example, is fussing about in Is There a Text in This Class?, not form. There is such a thing as formalism in criticism, but it’s not about examining form, rather it’s about using the existence of form as a conceptual device to treat the text, and its meaning, as an autonomous object.

I don’t by any means think that the issue of authorial intention simply disappears when it addresses matters of form. But the problems of answering it may well be different. In the case of meaning, we know that meanings are found in texts by special critical procedures that one must learn, and that different procedures will yield different meanings. David Bordwell has argued the case in some detail with respect to film criticism (Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema, 1989), but his arguments apply to literary criticism as well (indeed, much film criticism has borrowed its critical vocabulary from literary criticism).

In the case of “Author’s Prologue” it seems all but self-evident that Thomas consciously constructed that chiasmus. There’s no other way it could have gotten there.

But did he intend the reader to notice it? Ah, that’s a different question. When the reader gets to the middle, he or she is certainly going to catch the rhyme between “farms” (51) and “alarms (52) and then “keep” (53) and “asleep” (50). But whether or not the reader will then go on to examine the other rhymes, that’s a different matter. Yet Thomas left another very strong clue. The penultimate line of the poem – “At God speeded summer's end” is exactly the same as the second line. That’s easily enough noticed, and someone who notices it may well start digging around.

Still, did Thomas intend for the reader to dig around? I don’t know and am inclined to think the question irrelevant. He left clues. What the reader does with them is up to the reader, no?

Finally, we read lyric poetry differently than we read prose, like Hemingway’s Death in the Afternoon or any of his novels. Most prose fiction we read through from beginning to end – perhaps skipping over the dull parts – without much study and reflection. Lyrics are different. It’s not simply that they’ve got rhythm and they may have rhyme as well, but we tend to reread them. We savor them and contemplate them. That’s what that chiasmus is there for, to be contemplated, or to guide us in contemplation.

What we discover thereby, that is up to us.

Chiasmatic Pairs Compared

Each pair of lines consists of a chiasmatic pair, if you will. As Thomas’ “Author’s Prologue” has 102 lines, the first pair consists of the 1st and 102nd lines, the second pair has the 2nd and 101st lines, and so forth.

This day winding down now

And the flood flowers now.

At God speeded summer's end

At God speeded summer's end

In the torrent salmon sun,

My ark sings in the sun

In my seashaken house

Tom tit and Dai mouse!

On a breakneck of rocks

Ahoy, old, sea-legged fox,

Tangled with chirrup and fruit,

Huloo, my prowed dove with a flute!

Froth, flute, fin, and quill

Like wooden islands, hill to hill.

At a wood's dancing hoof,

Manned with their loves they'll move

By scummed, starfish sands

The water lidded lands,

With their fishwife cross

Cry, Multiudes of arks! Across

Gulls, pipers, cockles, and snails,

Under the stars of Wales,

Out there, crow black, men

We will ride out alone then,

Tackled with clouds, who kneel

And dark shoals every holy field.

To the sunset nets,

Poor peace as the sun sets

Geese nearly in heaven, boys

Of sheep and churches noise

Stabbing, and herons, and shells

Only the drowned deep bells

That speak seven seas,

With pelt, and scale, and fleece:

Eternal waters away

Drinking Noah of the bay,

From the cities of nine

Work ark and the moonshine

Days' night whose towers will catch

Felled and quilled, flash to my patch

In the religious wind

O kingdom of neighbors finned

Like stalks of tall, dry straw,

And barnroofs cockcrow war!

At poor peace I sing

Of waters cluck and cling,

To you strangers (though song

Hollow farms ina throng

Is a burning and crested act,

Hist, in hogback woods! The haystacked

The fire of birds in

Beasts who sleep good and thin,

The world's turning wood,

(Hail to His beasthood!).

For my swan, splay sounds),

On God's rough tumbling grounds

Out of these seathumbed leaves

But animals thick as theives

That will fly and fall

On atounged puffball)

Like leaves of trees and as soon

Hubbub and fiddle, this tune

Crumble and undie

(A clash of anvils for my

Into the dogdayed night.

Clangour as I hew and smite

Seaward the salmon, sucked sun slips,

Hears, there, this fox light, my flood ship's

And the dumb swans drub blue

Whisking hare! who

My dabbed bay's dusk, as I hack

Heigh, on horseback hill, jack

This rumpus of shapes

In your beaks, on the gabbing capes!

For you to know

Agape, with woe

How I, a spining man,

Ho, hullaballoing clan

Glory also this star, bird

Down to the curlew herd!

Roared, sea born, man torn, blood blest.

who moons her blue notes from her nest

Hark: I trumpet the place,

Coo rooning the woods' praise,

From fish to jumping hill! Look:

With Welsh and reverent rook,

I build my bellowing ark

in the hooting, nearly dark

To the best of my love

O my ruffled ring dove

As the flood begins,

Huloo, on plumbed bryns,

Out of the fountainhead

The dingle furred deer dead!

Of fear, rage read, manalive,

The flickering runs and dive

Molten and mountainous to stream

You king singsong owls, who moonbeam

Over the wound asleep

Hoo, there, in castle keep,

Sheep white hollow farms

To Wales in my arms.

Authorial intention: at the very least, the poet wants to keep the process of writing enough of focused rapture to avoid creating a shell of words around a solipsistic kernel of imaginative play. Doing this requires playing with rhyme schemes and line lengths to temper the images present and "crossing over" from the unknown. Stanzas likewise get thrown in to the mix. Whether the poet cares if the reader identifies such end-resulting schemes to be noticed --

ReplyDeletewell, who knows. Writing the poem is what matters first and last.

(Though I personally wrote one poem whose scheme is so deliberate and is just waiting to be called upon for discovery, though is not likely to be noticed much because the simplicity of lyric to many contemporary critics would look -- well," simple," simply because the form is so elegant it disappears into the poem entirely.)

Does all this say anything? LOL!

Thanks for this. I love this poem. This added to my enjoyment of it.

ReplyDelete