Note: I originally published this at 3 Quarks Daily earlier this year. But 3QD has just moved to a different platform and some of the posts haven't yet made it over. This is one of them. So I'm reposting it here.

* * * * *

Science fiction isn’t just thinking about the world out there. It’s also thinking about how that world might be—a particularly important exercise for those who are oppressed, because if they’re going to change the world we live in, they—and all of us—have to be able to think about a world that works differently.

–Samuel Delany

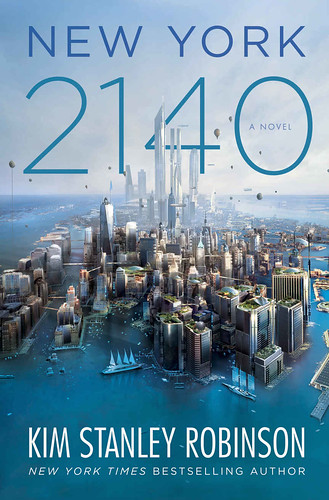

New York 2140, as many of you know, is Kim Stanley Robinson’s latest novel, a hefty doorstop of a book at a few pages over 600. The title tells the tale, well not all of it by any means, heck, not much of it at all, but it tips you to the central premise: this is a story set in New York City in the year 2140. After the flood. Actually, it’s after two floods, called pulses in the book, a term suggesting that they’re but inflections in the global climate system, though Robinson clearly believes that human activity ramped them up. Consequently, the sea in 2140 is much higher than it is now, fifty feet higher. Manhattan below 50th Street is under water, but most of the buildings remain. People live and work in them and get around by boat and by skybridges. And it’s like that all over the world. Coastal cities have flooded, but people remain.

It’s called the intertidal, this vast worldwide boondocks. It’s not fully wild, but it’s no longer fully civilized, whatever that means. It’s legally ambiguous, lots of off-grid activity, lots of informal mutual-aid living.

The two pulses have weakened nation-states in favor of private institutions and the world remains split into a large sprawling 99+% and a much smaller (fraction of) 1%, who rule over everything by speculating in real estate and financial instruments. New York 2140 is about how a small handful of 99 percenters living in one building in lower Manhattan manage to put a monkey wrench into the whole shebang and bring it to its knees. It is thus a comedy, in the literary sense of the word (e.g. Dante’s Divine Comedy), with an optimistic outlook.

I’m going to take a longish passage from about two-thirds of the way through and use it as a prism to examine the whole. It starts near the bottom of page 399 and continues to page 400:

Mutt, thinking to divert Jeff’s no doubt withering critique of their young financier, says, “Have you ever noticed that our building is a kind of actor network that can do things? We got the cloud star, the lawyer, the building expert, the building itself, the police detective, the money man...add the getaway driver and it’s a fucking heist movie!”“So who are we?” Jeff says.“We are the wise old geezers, Jeffrey”“But that’s Gordon Hexter,” Jeff points out. “No, we’re the two old Muppets on the balcony, cracking lame jokes.”“Lame-ass jokes,” says Mutt. “I like that.”“Me too.”“But isn’t it a little weird that we have all the right players here to change the world?”Charlotte shakes her head. “Confirmation bias. That or else representation error. I’m forgetting the name, shit. It’s the one where you think what you see is all of what’s going on. A very elementary cognitive error.“Ease of representation,” Jeff says. “It’s an availability heuristic. You think what you see is the totality.”“That’s right, that’s the one.”Mutt acknowledges this, but says, “On the other hand, we do have quite a crew here.”Charlotte says, “Everybody does. There are two thousand people living in this building, and you only know twenty of them, and I only know a couple hundred, and so we think they’re the important ones. But how likely is that? It’s just ease of representation. And every building in lower Manhattan is the same, and they’re part of the mutual aid society, and those are everywhere now, all over the drowned world. Probably every intertidal building in the world is just like us. For sure everyone I meet in my job is.”“So it’s mistaking the particular for the general?” Mutt says.“Something like that. And there’s something like two hundred major coastal cities, all just as drowned as New York. Like a billion people. And we’re all wet, we’re all in the precariat, we’re all pissed off at Denver and at the rich assholes still parading around. We all want justice and revenge.”

And that’s what it is, a heist movie, as though the Ocean’s Eleven series had continued on past 12 and 13 to, say, Ocean’s Ninety-Seven. Only now “ocean” isn’t the name of a thief, it is the Atlantic Ocean which, riled up by a hurricane, floods New York City. But that doesn’t happen until later in the book. At this point the heist is simply being planned.

Mutt, Jeff, and Charlotte are three of the planners, out of a crew of ten or so. As the story opens the crew don’t know one another. It takes Robinson 60 or so pages to bring them all on stage and a couple of hundred more to weave them all into a crew planning the heist of the century. Mutt and Jeff are the first ones we meet. They’re computing programmers working in finance who’re planning to hack the world-wide financial system. Until they disappear.

They disappear from temporary quarters in the Met Life tower, where Charlotte, the lawyer, is head of the co-op board. Her ex-husband is head of the Federal Reserve, a post which gives him some purchase on the ruling financial oligarchy. And since she remains on good terms with him, that gives our heist crew at least the beginnings of purchase on them as well. And, of course, there’s the software hack which Mutt and Jeff have been working on.

Some of you may be thinking, Isn’t “Mutt and Jeff” the name of an old-timey cartoon strip? Yes, it is. Names rang a bell as soon as I read them at the top of the first page. I even saw the strip as a kid, but didn’t read it. So I don’t know whether Robinson is playing off of it in any interesting way. You may also recognize “two old Muppets on the balcony” as a reference to Statler and Waldorf in The Muppets Show. I’m guessing it’s no more than that, but who knows? Without more context, however, you probably don’t know what “cloud star” means. She’s an entertainer who flies around the world in an airship moving specimens of endangered species from dodgy habitats to more hospitable ones. She’s got a world-wide following in the millions, and hence is a star, and her distribution medium is the digital cloud, presumably a continuation of the very same cloud through which you have access to 3 Quarks Daily.

So, we’ve got two programmers, a media star, a well-connected lawyer living in in the Met Life tower. They’re plotting a heist with the help of the building expert (that is, the building super), a money man, who runs a fund trading in securities pegged to the value of intertidal properties, the police detective (who plays a role in figuring out where Mutt and Jeff were disappeared to), and the building itself, described as “a kind of actor network that can do things”. Actor network is surely a reference to Bruno Latour, a philosopher and sociologist of science who has elaborated actor-network theory (ANT), which is a way of thinking about the world in which everything is an agent of some kind; Latour has also written about Gaia and climate change. Sure, people are agents, but so are pencils, and the paper they mark up, not to mention the table on which the paper rests, and the trees whose wood became paper and pencils and who knows what else, and the tools used in felling the trees, and so forth and so on. All these actors, inanimate and animate, interact act through networks, and one can even treat an actor-network itself as an agent. That’s what Mutt is saying about the Met Life tower, where they live. It’s an actor in the story.

It was built in the early 20th century in lower Manhattan – Robinson gives us its history – as an office building. It is now a residential co-op, with individual apartments being quite small. There is a large communal dining area where people can take meals – a number of scenes are set in this space – and a large area given over to indoor farming. There’s another area where people who have small boats can store them; our money man is one of these people. All of the central characters in the story live in this building – two of these characters, treasure-seeking teenaged boys aren’t mentioned in the quoted passage; they’re guided by that Gordon Hexter fellow – and consequently much of the book’s action takes place in the building. And much of the action – perhaps more – happens at various places in New York City as well, with the Met Life tower acting as a central hub. Our cloud star – her name is Amelia – roams as far as Antarctica. As the heist moves into high gear, action ripples around the world through that same cloud.

That brings us to the central statement in that passage: “But isn’t it a little weird that we have all the right players here to change the world?” Charlotte goes on to point out that every building is like that. Well, not every building, we know that. But a lot of them and they’re all over the world.

“There are two thousand people living in this building, and you only know twenty of them, and I only know a couple hundred, and so we think they’re the important ones. But how likely is that? It’s just ease of representation. And every building in lower Manhattan is the same, and they’re part of the mutual aid society, and those are everywhere now, all over the drowned world. Probably every intertidal building in the world is just like us. [...] Like a billion people. And we’re all wet, we’re all in the precariat, we’re all pissed off at Denver and at the rich assholes still parading around. We all want justice and revenge.”

It’s a modular world they’re living in – bees in a hive? The Met Life module is pretty much like all the other modules in some important respects: its inhabitants are precarious and aching for justice and revenge.

That’s what’s required for this particular heist to work, a population eager for change and ready to move. You’ll have to read the book to get the details of the heist – it’s nothing so crude as scoring a huge pile of cash. The billion in the precariat are ready to move. Our heist crew simply figures out a scheme that sets them off. That scheme involves broadcasting in the cloud, buying out the Met Life tower (with the treasure our two teen-aged boys uncover) manipulating the financial system, and getting the Federal Reserve and, more generally, the federal government to do the right thing, which is rather different from what happened in the wake of the financial collapse of 2008.

And the book itself is modular. Well, all books, indeed all texts, are modular. Sentences constructed of words, paragraphs of sentences, chapters of paragraphs, and the book of chapters. But Robinson has constructed New York 2140 in a way that emphasizes its modular structure. It consists of eight main sections, each called a part and each numbered along with a descriptive label: “Part One. The Tyranny of Sunk Costs”, “Part Two. Expert Overconfidence”, and so forth. Each part consists of eight or sometimes nine chapters, each designated by a letter and the name of a character: “a) Mutt and Jeff”, “b) Inspector Gen”, and so forth. Each of these named chapters emphasizes the named character but, as things get rolling, other characters will be called on in a given chapter.

The story itself is contingent, opportunistic, chaotic, and thus self-organizing. The characters are strangers to one another at the beginning and only gradually come in contact with one another. It’s almost as though Robinson reached into a random living module (aka building) full of characters, pulled out a random handful, set them down, and then let them go about their business. He could have reached into any module and likely gotten a similar result, though the specific pattern would differ in countless details. But this is the one he chose.

It takes awhile for these characters to learn one another’s business enough for a plan to emerge, here and there, and awhile for them to trust one another to move toward execution. Then plan never gets fully formed before a post hurricane storm surge begins forcing things. And then our cloud star jumps the gun, as if there were anything so specific as a gun to be jumped. At that point everyone scrambles.

And the result, I find, is satisfying. It gives me hope that perhaps we can cope our way out of the mess we’ve boxed ourselves into. It’s a convincing fiction, perhaps even a true lie.

* * * * *

I began writing and thinking about New York 2140 in comments to Leanne Ogasawara’s post, Knowing Bitter Melon and Global Warming (知行合一).

No comments:

Post a Comment