Unlike Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which has no talking animals, Dumbo has many of them, and talking humans as well. In this post I want to look at who talks, and in the case of Dumbo and his mother, who doesn’t, and examine how that talk, or silence, functions in the film.

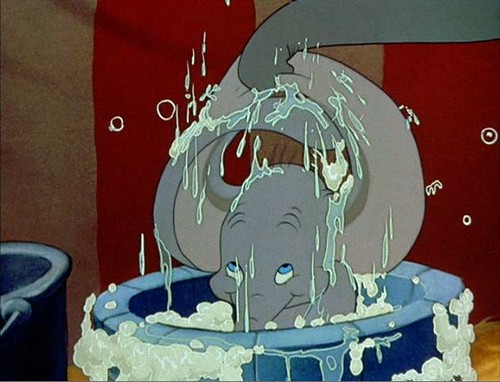

The first talker we encounter in Dumbo is the stork who delivers him. Then we hear the elephant matrons, and one line from Mrs. Jumbo, when she utters her son’s name, which is the only line she speaks in the film. Later, after the tent’s been put up in the middle of a stormy night, after the opening day parade, and after Dumbo’s had a bath, we hear the first human talking, a barker drawing the crowed to the side shows and the menagerie (plus crowd chatter). The next human to talk is the brat who taunts Dumbo (more chatter).

I’m going to start with those talking humans, move on to the others, and then move on to the animals, talkers and non-talkers, move to the peculiar case of Timothy Mouse, and conclude with a comparison to Pinocchio.

Humans Talking

So, Dumbo has concluded his bath, he ventures toward the crowd as he hears the barker and gets noticed by a big-eared boy, who taunts him, remaking how odd he looks—with lots of crowd chatter in the background. This leads to the first crisis in the movie, when Mrs. Jumbo spanks the boy and then goes berserk. That brings the ringmaster running: “What’s going on?...Surround her. ” Thus yet another human speaks, one who’s the boss of the circus and thus the authority in the story.

We hear from him several more times. We hear him when he introduces his spectacular new act, an introduction which prompts cynical remarks from the elephants actually performing the act. But we also hear him at night, in his tent.

The first time is when he’s talking to his assistant about a new act and later that night when he’s gotten the brilliant idea suggested to him by Timothy Mouse. In that conversation with his assistant we don’t see either of them directly. Rather we see them in silhouette against the tent wall. THAT’s what I want to talk about. We see the same motif while eavesdropping on the clown conversation, which is the other major bit of human-talk in the film.

While I’ve previously suggested that this may have been a cost-saving measure—the budget was tight on this film—it also has thematic significance. Just who are those clowns, anyway? Would we recognize them as individual people? Would we know how to match voices to faces?

That would be difficult. They’re wearing make-up during their act, which disguises them. And we don’t see their faces in the silhouette views, though we can see whether or not a clown is talking. But it would certainly be difficult to match those voices to faces if we saw them.

The effect is one of depersonalization. These voices don’t come from particular individuals. They’re just ‘in the air’ as it were. They’re voices of The Organization, not of people. That is, the voices underline the operations of the circus as a social mechanism for turning entertainment into profit. They thus play into the thematics of Fordism and machine as social organization that I discussed in Dumbo as Myth 2.2: Machines and Fordism.

Animal Talk

Most of the animal talk comes from the elephant matrons, the crows, Dumbo’s stork, and from Timothy Mouse, but not from either Dumbo or his mother. So, on the one hand we have the matrons and, on the other, we have Dumbo’s associates (the stork, Timothy Mouse, and the crows) but not Dumbo himself.

The stork and the crows are outsiders to the circus, which forms the core community in the film, a matter I’ll return to in the next post. The stork brings Dumbo into the world while the crows help restore him to society. But once their tasks have been complete, the stork and the crows are not needed.

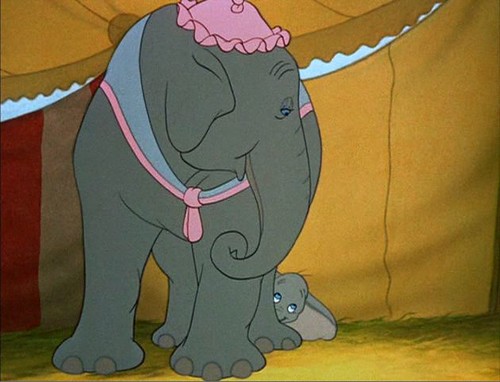

Within the circus community, Dumbo and his mother do not talk to one another, nor do they talk to the matrons. But they communicate with one another quite a bit, nonverbally. When Dumbo is first delivered Dumbo sneezes Mrs. Jumbo ends up rocking him in her trunk. She does the same thing when he visits her at night. They don’t talk, but they do touch. And they touch at the very end of the film, when Dumbo flies into her arms as she’s setting at the rear of the train.

Their major scene occurs after Dumbo steps in the mud in the opening day parade. She baths him and they have a grand time playing together, first with Dumbo in the bath and then afterward, as he plays hide-and-seek amid her legs.

Their bond, and their relationship, is deeper than language. The point is so obvious that it seems trite, but one reason the point is obvious is that a most of the work on non-verbal human communication has been done after Dumbo was filmed and viewed. We are heirs to a lot of writing, both scientific and popular, that wasn’t available to Disney and his audience.

The film separates verbal and nonverbal communication and builds its central relationship, that between Dumbo and his mother, on nonverbal communication. And THAT is hardly a trivial statement about human psychology and society. I note in passing—for I want to move on to Timothy Mouse—that there’s a lot of nonverbal communication, shouting and elephant trumpeting, in the two disaster scenes, Mrs. Jumbo’s panic and the collapse of the elephant pyramid and, subsequently, the Big Top itself.

Timothy the Talking Mouse

Timothy Mouse first appears when the matrons shun Dumbo after his mother has been imprisoned. He first sympathizes with Dumbo, then he scares and chastises the matrons, and then he seeks Dumbo out and befriends him. In the last third of the film he negotiates Dumbo’s relationship with the crows and, judging from a magazine cover in the concluding collage, negotiates Dumbo a nice fat Hollywood contract.

Before those negotiations, however, he brokers a very peculiar deal with the ringmaster. The deal is peculiar in the first place because the ringmaster doesn’t know what’s going on. Timothy speaks to him in his sleep. It’s peculiar in the second place because it backfires. It was supposed to secure Dumbo’s place as a star in the circus, but it just makes matters worse, ending in the collapse of the Big Top and the matrons declaring Dumbo to be a non-elephant.

This was not Timothy Mouse’s fault, of course, nor was it Dumbos. But then, we’re not dealing with ordinary cause-and-effect logic, either. We’re dealing with Myth Logic. Within the peculiar conventions of myth logic this deal has to be made, and it has to collapse, thus forcing Dumbo to seek help outside circus society.

Dumbo and Pinocchio

A full explanation of that myth logic will have to wait for the next post. But I can lay the foundations here by comparing Dumbo with Pinocchio. Consider this table of relationships:

| Role | Pinocchio | Dumbo |

Parent

|

Geppetto

|

Mrs. Jumbo

|

Child

|

Pinocchio

|

Dumbo

|

Little Mentor

|

Jiminy Cricket

|

Timothy Mouse

|

Supreme Authority

|

Blue Fairy

|

Ringmaster

|

It’s perhaps a bit of a shock to see the Blue Fairy and the Ringmaster equated to one another in that way. After all, the ringmaster is presented as a thoroughly dislikeable and despotic character. Yet without him there’d be no circus.

In contrast, the Blue Fairly is presented as kind and wonderful, especially since she comes to Pinocchio’s rescue once he’s messed up by joining Stromboli’s marionette show. Yet she did make a deal with Pinocchio, and Jiminy, and we can only assume that, if they hadn’t managed to come through, she’d have let Pinocchio remain a puppet.

In both cases our protagonists have to screw-up royally before they can succeed. Pinocchio runs off with Stromboli while Jiminy was having trouble waking up—actually he runs off with Honest John the fox and Gideon the cat who then take him to Stromboli and, by the time Jiminy is there to offer advice, it’s too late. Dumbo ends up in an impossible act that was negotiated on his behalf by Timothy. It’s not Jiminy’s fault that he was unable to persuade Pinocchio to go to school once he’d been hooked him and it’s not Timothy’s fault that Dumbo’s awkwardness impedes him from performing the role he’d negotiated for him. In both cases the result is the same; the child protagonist ends up in even deeper trouble.

If Jiminy’s mythic blunder is one of omission—he doesn’t wake up in time—while Timothy’s is one of commission—he negotiates a bad deal—we can attribute that difference to the overall difference of their respective stories. [Putting on my tap shoes.] Pinocchio has to negotiate the transit from inanimate puppet to live boy, a transit that, in myth logic, requires the role of Supreme Authority to be played by a supernatural creature, the Blue Fairy. Dumbo only has to negotiate the transit from physically deformed elephant to flying elephant, which, though something of a stretch, is not as extreme as from nonliving to living. So, myth logic allows the role of Supreme Helper to be a merely human, but nonetheless stern taskmaster.

In the case of Pinocchio and his helper, Jiminy Cricket wants something from the Supreme Authority, a gold medal, while Timothy Mouse wants nothing from the ringmaster. In fact, he’s trying, surreptitiously, to help him with his problem—finding a climax for this new act he’s dreamed up—while the Blue Fairy has no problem she’s trying to solve.

These differences between these two sets of characters in these two films all seem of a piece to me, though I can’t quite sum them up in a simple paragraph ending in a simple sentence. It’s all Myth Logic.

Growth

A more pressing problem is why the protagonist has to fail before succeeding. That fact that that’s just how it goes is of little use. Why does it go just like that?

Both movies present us with stories about protagonists who have to grow. In one way or another growing means moving beyond yourself. Neither of our protagonists did anything to acquire a mentor; the mentor just showed up and volunteered for service. And so both must move beyond that mentor.

Dumbo fails at an act Timothy set up for him. But he flies with the encouragement of some wise-ass crows AND without the magic feather they gave to him. In parallel, Pinocchio saves Geppetto from drowning even as Geppetto was urging him to save himself. Thus both protagonists were pushed beyond themselves.

Further, myth logic requires that Pinocchio, who was created by a wood carver, must pass through a living creature in order to become a boy. And Dumbo, who was delivered from the air, must himself learn to fly in order to take his place in the world.

More later.

No comments:

Post a Comment