Another working paper. Title above, abstract, TOC and introduction below.

Download at:

- Academia.edu: https://www.academia.edu/27132290/Miyazakis_Metaphysics_Some_Observations_on_The_Wind_Rises

- SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2812252

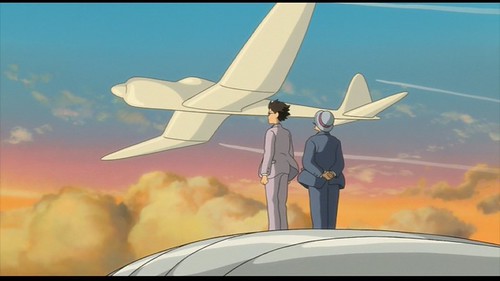

Abstract: In The Wind Rises Hayao Miyazaki weaves various modes of experience in depicting the somewhat fictionalized life of Jiro Horikoshi, a Japanese aeronautical engineer who designed fighter planes for World War II. Horikoshi finds his vocation through ‘dreamtime’ encounters with Gianni Caproni and courts his wife with paper airplanes. The film opposes the wind and chance with mechanism and design. Horikoshi’s attachment to his wife, on the one hand, and to his vocation on the other, both bind him to Japan while at the same time allowing him to separate himself, at least mentally, from the imperial state.

CONTENTS

Making Sense of It All: Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises 2

Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, Some Observations on Life 6

Some Thoughts about The Wind Rises 9

The Wind Rises, It Opens with a Dream: What’s in Play? 10

Horikoshi at Work: Miyazaki at Play Among the Modes of Being 23

The Pattern of Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises 31

From Concept to First Flight: The A5M Fighter in Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises 32

Why Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises is Not Morally Repugnant 40

Horikoshi’s Wife: Affective Binding and Grief in The Wind Rises 49

The Wind Rises: A Note About Failure, Human and Natural 57

Problematic Identifications: The Wind Rises as a Japanese Film 59

How Caproni is Staged in The Wind Rises 67

The Wind Rises: Marriage in the Shadow of the State 89

Miyazaki: “Film-making only brings suffering” 99

Counterpoint: Germany and Korea 100

Wind and Chance, Design and Mechanism, in The Wind Rises 103

Appendix: Descriptive Table 112

Making Sense of It All: Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises

I was going great guns writing about The Wind Rises in November and December of last year. And then the energy ran out while I was drafting “Registers of Reality in The Wind Rises.” Here’s the opening paragraph:

The term, “registers of reality”, is not a standard one, and that’s the point. It’s not clear to me just what’s going on here, and so we might as well be upfront. But it has to do with those “dream” scenes, among other things. And it’s also related to what seems to be a common line on The Wind Rises, namely that while all other Miyazaki films have elements of fantasy in them, often strong ones, this does not.

Many of the reviews casually mention those so-called dream sequences. You can’t miss them. They seem, and are in a way, typical of Miyazaki. But if you look closely you’ll see that they’re not all dream sequences, not quite. Without getting to fussy let’s all them dreamtime with the understanding that sleep is only one of the occasions of dreamtime, that one can enter it under various circumstances–a discussion I open in the posts, “The Wind Rises, It Opens with a Dream: What’s in Play?” and “Horikoshi at Work: Miyazaki at Play Among the Modes of Being.” And they happen only in the first half of the film and at the very end. That’s one thing.

But I had more in mind with the phrase “registers of reality.” A couple paragraphs later in that incomplete draft:

That’s one set of questions. What’s the parallel set of questions we must ask about Horikoshi’s relationship with Naoko Satomi? I ask that question out of formal considerations. As I pointed out in an early post in this series, “The Pattern of Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises”, Horikoshi interacts with Caproni in the first half of the film and with Naoko in the second half. His meetings with Caproni didn’t take place in ordinary mundane reality. What about his meetings with Naoko?

All of those meetings DO take place in mundane reality. The first half of the film alternates between mundane reality and dreamtime (whether waking or sleeping). The second half alternates between work-time and Naoko-time. But the two are, of course, symbolically related. The object of the “registers of reality” post was to make sense out of all this, out of how Miyazaki weaves them together–mundane and dreamtime, work and love–into a life.

But it got too hard, just too hard. And so I stopped. I had other posts planned, including one on “Unity of Being in The Wind Rises.” I’ll get back to it one day. I need to. Perhaps it will take more conceptual apparatus than I can work up in a blog post. Who knows?

That was half a year ago and I’ve not yet gotten back to it. I’ve decided to take the work I’ve done and assemble it into a working paper. Before I do that, however, I can at least indicate something of where I was going, of where I hoped to arrive.

Naturalist and Ethical Criticism

By naturalist criticism I mean a criticism that treats literary works, films, and other artistic phenomena as phenomena of the natural world along with plants, planetary bodies, and plasma. Naturalist criticism aspires to objective knowledge and seeks to ground it in rich description, as biology is grounded in the description of life forms, macromolecules, and physiological systems [1]. As such my posts on The Wind Rises have been largely, though certainly not completely, engaged in describing what happens in the film.

I regard this as comparable to what a naturalist does in describing a species of plant or animal. In an ideal world other critics will examine what I’ve put on offer and make suggestions for change, correcting things I’ve gotten wrong and adding features I didn’t describe. In time we would negotiate a description of the film.

But that is not all, of course. One might want to know what transpires in a person’s mind/brain as they watch the film – I certainly would. A good descriptive account won’t do that, any more than an accurate description of an animal’s form would tell about the operations of its internal organs. The description, though, would be a necessary starting point.

Let’s set that aside. Even if we knew how to do it, there’s more. Is it a good film? You can’t decide that from a description nor, I believe, can you decide it from an account of how it works in the mind. And just whose mind are we talking about, for surely there are differences here.

I have adopted unity of being as my criterion for making an aesthetic judgment. Does The Wind Rises promote unity of being in the viewer? Alas, I don’t really know what I mean by unity of being. Rather, my intention is to figure it out by making an argument based on a description of the film on the one hand and my subjective experience of the film on the other.

I like the film. It makes me feel good. It is a matter of subjective experience. And so I’m going to say that it promotes unity of being. How does it do that? Well, it has these features, and they fit together like this. And so on. And yet the film may work for me at one time, but not another. It may not work for me in the same way that it works for you–but how do we determine that? Hence the need for critical discussion.

Those discussions will be ethical in character, where I mean ethical in the sense of ethos, a way of life [2]. If you will, a film that is aesthetically good promotes a life that is ethically good. I could in fact make such an argument now. In a way the existence of this working paper is an implicit argument that this is a good film, for I wouldn’t be doing all this work if I didn’t think that The Wind Rises is good. The mere fact that it is a complex object is not enough to draw this work from me.

Moreover, you will find indications of an ethical argument in the various sections of this working paper, more in some than others. It is mostly descriptive, but not entirely so. But a focused argument for unity of being, no, you won’t find that here. You won’t even find the phrase beyond this introduction.

As always, there is more work to be done.

What You’ll Find in the Rest of this Working Paper

Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, Some Observations on Life–In which I suggest that the film is (retrospectively) about making sense of the complexities of living in a world you can’t control. Horikoshi loves aircraft, and designs them for a state he distrusts, and he loves his wife, whom he knows will die young, of tuberculosis. How does one (Miyazaki) pull all that together into a life?

Some Thoughts about The Wind Rises–In which I observe that the film falls into two parts. In the first Horikoshi lives in counterpoint to Gianni Caproni, and Italian aircraft designer he admires and meets in dreams. In the second part Horikoshi lives in counterpoint to a tubercular woman he weds (while at the same time designing war planes for a war he doesn’t believe in).

The Wind Rises, It Opens with a Dream: What’s in Play? – This is a close analysis of the opening dream sequence, the one in which young Horikoshi’s dream of being a pilot crashes and burns on the matter of his poor eyesight. These four minutes prefigure the course of the film. Loaded with frame grabs.

Horikoshi at Work: Miyazaki at Play Among the Modes of Being–I examine how Miyazaki interweaves different modes of being (a term from Latour), imagination and action, in the first 40 minutes of the film, such that each mode contributes to The Real.

The Pattern of Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises–I suggest that the film is a ring-composition with the central episode being the one where Horikoshi is made the chief designer on a new project. Before that point he had dreams of Caproni; after that point he courts and marries Naoko Satomi.

From Concept to First Flight: The A5M Fighter in Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises–I follow the genesis of the AM5 from midway in the film, when its general form appears in a Caproni dream, through his courtship of Naoko (conducted with paper airplanes), though to the successful test flight at the end.

Why Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises is Not Morally Repugnant–No, I don’t think it is: morally repugnant. But it IS controversial and problematic, and that’s what I want to deal with in this post. Here I consider the fact that, after all, Horikoshi designed airplanes the led to the deaths of tens of thousands of people and I discuss objections by the critic, Inkoo Kang.

Horikoshi’s Wife: Affective Binding and Grief in The Wind Rises–Horikoshi’s fiancée and wife is visually associated with Mount Fuji and with cherry blossoms, both associated with Japan itself. Thus to grieve for her is symbolically to grieve for Japan, for the state that lost the war.

The Wind Rises: A Note About Failure, Human and Natural–While Horikoshi is fighting fires in a Tokyo that has been devastated by an earthquake he also talks with Caproni, who has just lost an airplane he very much wanted to build. What do we make of this juxtaposition?

Problematic Identifications: The Wind Rises as a Japanese Film–The Wind Rises summons a network of identifications that aren’t implicated in any of Miyazaki’s other films and implicitly distinguishes between Japanese culture and the imperialist state of the first half of the 20th century. If you are Japanese, what do you think about the Empire and its wars? That question will have one valence if you are old enough to have come of age during the Empire, but a different valence if, like Miyazaki, you are too young to ever have identified with the imperial regime. If you are not Japanese, your encounter with the film is likely to be colored by your nation’s relation to imperial Japan. At the end I offer some other films that set up problematic identification: Das Boot, Letters from Iwo Jima, and The Thin Red Line.

How Caproni is Staged in The Wind Rises–I take a close look at the Caproni sequences. There are four of them. It’s easy to call them dream sequences. But that classification doesn’t survive close examination. Yes, two of them are obviously dreams. But one is not – Horkoshi is fully awake as he fights fires in Tokyo. Nor is it at all clear what the film’s final sequence is.

The Wind Rises: Marriage in the Shadow of the State–A close examination of Naoko’s decision to leave the sanitarium, their joint decision to marry, the (improvised) ceremony itself, and the wedding night. Miyazaki has staged this marriage as taking place at the margins of society. Noako is tubercular and may not live much longer and Jiro is in hiding from the secret police, even though he’s working on the design of a plane for the Japanese military. We normally think of marriage as binding individuals more deeply into society. In The Wind Rises, this marriage has almost the opposite effect, that of creating an imaginary boundary around Naoko and Jiro that keeps them separate from society.

Miyazaki: “Film-making only brings suffering” –A short note about a documentary, The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, which has made about Studio Ghibli in 2012 or so while The Wind Rises was being finished. After the staff screening, Miyazaki remarks, “This is embarrassing, but this is the first time I cried at my own film.”

Counterpoint: Germany and Korea – This section combines two posts about new items that have some bearing on The Wind Rises. The first is about how most Germans regarded World War II. The second is about Korean “comfort women”, women coerced into sexual slavery for the Japanese military.

Wind and Chance, Design and Mechanism, in The Wind Rises –The wind is an important motif in the film, obviously, and it is associated not only with flight, but with chance. It functions in tension with deliberate design, where the objects being designed are airplanes. Airplanes fly with the wind, but are also subject to it.

Appendix: Descriptive Table– This table is a work in progress. I build such tables in order to get a better sense of how a narrative lays out. You should be able to locate (many of) the scenes I discuss throughout this working paper, locate them in this table.

References

[1] I adopted naturalism as a label in a long theoretical and methodological article, Literary Morphology: Nine Propositions in a Naturalist Theory of Form. PsyArt: An Online Journal for the Psychological Study of the Arts, August 2006, Article 060608: http://www.psyartjournal.com/article/show/l_benzon-literary_morphology_nine_propositions_in. I discuss my use of the term itself in an informal and tactically rambling blog post, “NATURALIST” criticism, NOT “cognitive” NOT “Darwinian” – A Quasi-Manifesto, which I published originally on March 31, 2010 in The Valve and republished in New Savanna on August 9, 2014: http://new-savanna.blogspot.com/2011/06/naturalist-criticism-not-cognitive-not.html.

[2] For discussion of ethical criticism see my post, Some Notes on Ethical Criticism, with Commentary on J. Hillis Miller and Charlie Altieri, New Savanna, September 10, 2015: http://new-savanna.blogspot.com/2015/09/some-notes-on-ethical-criticism-with.html, and my working paper, Literature, Emotion, and Unity of Being, September 2014: https://www.academia.edu/8296741/Literature_Emotion_and_Unity_of_Being.

No comments:

Post a Comment